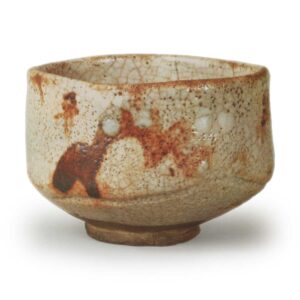

Height: 8.7 to 9.5 cm

Diameter: 12.1 to 12.9 cm

Outer diameter of foot ring: 5.3 to 6.0 cm

Height of foot ring: 0.9 cm

When it comes to famous Shino bowls, the Asahagi is one of the most famous, and it has been renowned since ancient times.

The brushwork of the Asahagi, with its lively and vigorous strokes of vermilion lacquer on a black background, is known to be the work of the calligrapher Matsudaira Fumai, and it is listed as a famous item in the Unshu Zocho (a book of famous items from the Unshu region). In other words, the inscription “Asahagi” is the name given by Fumai himself, and it is thought that he likened the picture of the fence to the way that the leaves of the autumn bush clover wave in the wind, and that he saw the white glaze spots spots are likened to morning dew, and the overall impression of a graceful elegance in a refreshing atmosphere is truly well expressed by the name “Asahagi”.

The white, soft clay is covered in a thick layer of the snow-white feldspar glaze that is the most distinctive feature of Shino ware, and beneath the glaze, the thick, dark underglaze designs that are a hallmark of Koshi ware are faintly visible. The rough, cracked glaze is covered in the characteristic holes that are a feature of Koshi ware, and the glaze pools inside and out create a beautiful scene. The rim of the mouth and some of the cast pictures have a hint of the distinctive Shino fire color, adding a touch of severity to the pure white background and giving off a beauty that is unique to Shino. The cast pictures are also drawn in a brush-like pattern in two places around the rim, with three eye marks in the middle.

The mouth is almost round, but the overall shape is irregular and polygonal, with the rim uneven and the waist almost triangular and also uneven, and as if to emphasize this, a thick, wavy brush stroke runs down one side. The base is steep and the shape is like a standing up, and the attached foot is also irregular and deviates from the center in a hand-made style.

In other words, what is evident here is a strong desire for deformation in the forming process, and the unrestrained touch of the painting is also appropriate for this. This tendency towards distortion is rooted in the modern desire to break down standard forms and create unique expressions, and is actually something that can also be seen in general Shino and Oribe tea bowls. It is ironic that this originally free and individualistic style, which aimed to be varied and unique, eventually evolved into the more formulaic style known as sankin.

However, in this Asahagi tea bowl, the deformation has not yet reached the point of becoming stereotyped, and it is full of the creative freedom of Koshin, and exudes a relaxed mood. From the perspective of a tea master, this would be described as having a mysterious charm and being rich in elegance, but in the Asahagi, there is also a dignified quality that can be felt in the particularly generous molding and bold cast pictures. It is truly no wonder that it was also appreciated by the daimyo tea master Matsudaira Fumai. In the suburbs of Mino-Okaya, where the famous Ko-Shino wares of the Momoyama period, including Asahagi, Uka-gaki, Hirosawa, Hagoromo, Sumiyoshi, Yamahata and Mine-momiji, were born, there were several outstanding potters, and their unique and creative expressions were freely and unrestrictedly expressed to the full. the characteristics of each style can be seen, and they can be divided into two types. Among them, the Asahagi does not become unnecessarily strong, and it even has the appearance of a leisurely and unhurried courtier, and it has an endless taste of elegance.

It is slightly tall, has a deep interior, and is also wide and pleasing, and is flawless, with only four vertical cracks running from the rim to the inside.

Transmitted: It was transmitted from the Higuchi family of Kyoto, and became the property of Fumai through the mediation of the tea utensil dealers Takeya and Fushimiya. It is listed in the upper section of the Unshu Zocho. Around 1923, it was transferred from the Matsudaira family to the Dan family, and after the Second World War, it was placed in the home of a certain family that had been in business since the Edo period.