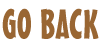

Porcelain from Arita, Hizen Province (Saga Prefecture). Arita porcelain was the first porcelain produced in Japan under the sheath, and was made from materials discovered in Arita Izumiyama after the Japanese invasion of Japan in 1592-8. It is also called Imariyaki because most of the products were shipped out through the port of Imari.

The founder of the Saga Domain, Nabeshima Naoshige, was the spearhead of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s expeditionary force to Korea, and many potters were brought with him and became naturalized citizens. Among them, those who lived in Kuma-yama, Kanadachi-mura, Saga County (Kanadachi-machi, Saga City) were called the Kane clan, and later moved to Aza Fujinokawauchi, Yamagata-mura, Matsuura County (Yamagata, Matsuura-cho, Imari City). Those who resided in Taku Village (Taku City), Ogi County were called the Yi family and were from Kanegae, Chungcheongnam-do, Korea. Later, he changed his name to Kimgae Sanbei, and a later person was named Yi Sanpei. At first, he started his business in Dosomoto, Aza, Arita Village, but he could not find suitable raw materials, so he gradually moved westward to Ranbashi, Arita Township, Matsuura County in 1616 (Genna 2), and then to Kamishirakawa, Arita, Arita. Those who lived in Aza Uchida, Takeo Village, Kishima County (Oaza Uchida, Higashikawatomachi, Takeo City) were called Soden, whose family name was Fukami, and later moved to Aza Hiekiba, Arita. They must have made their living by the pottery business for more than 20 years from Keicho (1596-1615) to Genna/Kan’ei (1515-44). At that time, Arita Town was called Tanaka Village, and there was only a road leading from Hirado, Matsuura County (Hirado City, Nagasaki Prefecture) to Takeo, Kishima County (Takeo City, Kishima Prefecture) in a thickly forested valley. This is thought to be because the area was extremely convenient for wood and water. The Quanshan Porcelain Mine was discovered by Sanpei Lee, and at the time of its founding, it was so poorly made that no one paid much attention to it, but in retrospect, it was the beginning of a revolution in Japanese pottery production, and it is truly to Sanpei’s credit that the Arita pottery industry exists today.

The fact that he had already discovered the porcelain clay of Izumiyama and created white porcelain ware in this area is evidenced by the fact that fragments excavated from the ruins of the abandoned kiln show the porcelain clay of Izumiyama. However, since this area was very remote and transportation was inconvenient, the kiln was moved to Aza-Otaru, which is adjacent to a road. It is said that the kiln was built again around 1810 (Bunka 7), and this was called the “new kiln,” which is now the character for this area.

The fact that the existence of the kilns after that time has been uncertain can be imagined from the fact that the ruins of abandoned kilns can be seen scattered in various places. This is because not only naturalized Koreans but also people from far and near came to Arita to work in the pottery industry. These craftsmen later scattered throughout the region, creating villages and cutting down forests to engage in the pottery business.

In 1637, the feudal lord Katsushige Nabeshima ordered Shigetatsu Taku, the chief retainer of the domain, to extensively eliminate all personnel (532 males and 294 females out of 826), and prohibited all but naturalized Koreans from engaging in the pottery business and forced them to leave the domain.

This was due to the fact that local people were learning pottery from Koreans, and the local forests were cut down to use as fuel. However, those who were related to Koreans (at that time, Yi Sampyeong had more than 30 descendants and apprentices) or those who had succeeded in this business for many years were allowed to continue working in the business, especially with the trust of the Taku family. At this time, thirteen places in Arita and other areas were designated as potteries, and a small amount of money was paid as a tax for cutting down forests. In 1655 (Meireki 1 or 1652, also known as Jouou 1), Sanpei died in Kamishirakawa, Arita. His grave is in Hoonji Temple. At that time, he had mastered the techniques of blue-and-white painting on white porcelain, ice crack patterns on celadon, and model engraving on white porcelain in place of pictorial motifs.

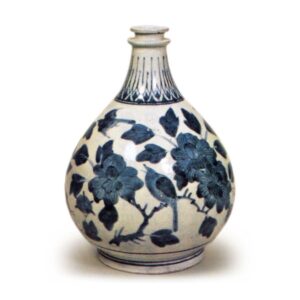

In 1644 (Shoho Gen), Tojima Tokuemon, an Imari potter, learned the technique of coloring with Chinese paints from Shuchinkan, a Chinese potter who had come to Nagasaki, and passed it on to Sakaida Kakiemon, a potter in Minamikawara, Arita. Kakiemon experimented with various methods without success, so he consulted with Kuresu Gombei, and together they conducted numerous studies until they finally succeeded. Kakiemon then sold the first porcelain made by Kakiemon to Chinese merchants of the Qing dynasty in Nagasaki, where it was greatly admired. This was the beginning of the sale of Arita porcelain to foreign merchants. This was in 1646 (Shoho 3), and from then on, he traded with Qing dynasty merchants and exported exquisite porcelain with painted brocade patterns.

In 1647 (Shoho 4), the number of households engaged in the pottery business in Arita and 13 other pottery-producing areas was limited to 150, and therefore, the number of households equipped with pottery-making machines (kick wheels) was also limited to 150. At this time, the tax on forest logging was abolished and a small amount of money was imposed as a wheel tax per wheel. The distinction between “Uchiyama” and “Oyiyama” was also established at this time. The following mountains were designated as “Uchiyama”: Mt. Sotoo, Mt. Kuromuta, Mt. Oho, Mt. Oho, Mt. Hirose, and Mt. Minamikawara in Arita Township, Mt. The outer mountains are also called “Ootai-yama” (big outer mountains). Some of these mountains were called “Outer Mountains” and some were called “Outer Mountains” and some were called “Outer Mountains”. This system was established in later times, but it was generally determined according to the territorial divisions of the lords. The Sotowo-yama, Kuromuta-yama, Oho-yama, Hirose-yama, Minami-kawahara-yama, Okawachiyama, and Ichinose-yama in Matsuura-gun were the territory of the Nabeshima clan of the main domain. Although there were differences in the quality of the raw materials used, they were all made from materials produced in Arita. This is called “Sotoyama.

Tsutaeyama, Yuminoyama, and Odashiyama in Kishima County were the domain of the Nabeshima family, and therefore, it seems that they were not allowed to take materials produced in Arita. However, the reason why 85,000 kg (about 50 tons) of Arita material was allowed to be extracted from Tsutaeyama every year may be due to the fact that a part of the Joseon family who used to work at the Hyakuman Kiln in Itanokawauchi moved there and established a pottery business there when the kiln was closed down. The ruins of the kiln still exist in Miyano Aza Tsutsue, Yamauchi Town, Kishima County. Shida Higashiyama in Fujitsu-gun was the domain of the main domain, but was established late, and Nishiyama was the domain of a branch domain, so it seems that both were not allowed to use materials from Arita. Uchinoyama was the domain of the main clan, but it was not necessary to use materials from Arita because the products were made in crude form. Yoshida was divided between the main clan and its branch clans, and only those belonging to the main clan were allowed to take 500 bracts of Arita material every year from 1752. These mountains are called “Ootoyama.

The Okawachiyama kiln was originally located in Iwayakawa, Arita, and was moved to Minami-kawaharayama during the Kanbun era (1661-73), and then to the present Okawachiyama during the Empo era (167381). Enpo period (167381) to the present Okawachi mountain. The raw materials were especially mined in the Arita Izumiyama porcelain mining area, which was called an “imperial mine” and was not allowed to be mined unnecessarily. Magosaburo Soeda, a samurai of the clan, was in charge of the factory, and he had been in charge of it for generations. He made the products, mainly sake cups, and other exquisite ornamental tools, and strict regulations were set to prohibit others from imitating them. In the Tenmei era (1781~9), the kiln was placed under the jurisdiction of the Arita governor and a bailiff was stationed to supervise all the kiln workers.

In 1656 (Meireki 2), the forestry system was once again reformed, and the car tax was changed to the car transport tax (today’s production tax), and a law was established for its collection. In 1656 (Meireki 2), the forestry system was revised again, and the car tax was changed to the car transport tax (today’s manufacturing tax) and a law was enacted to collect the tax.

In the Kanbun period (1661-73), Imariya Gorobei, a potter in Edo, came to Arita on commission from the Sendai domain and sought porcelain, but was unable to obtain any. The marquis greatly admired its excellence and presented it to the imperial family. As a result, the imperial family abandoned the earthenware used since ancient times in favor of blue-and-white porcelain, and the lord of the Saga domain ordered Kiemon Tsuji to prepare and deliver some of the imperial vessels to the imperial household every year. In 1672, the name “Akaecho” was given to the town.

During the Kyoho era (1716-36), Tomimura Kan’emon of Arita Otaru, in conspiracy with Ureshino Jirozaemon of Akae-machi, often violated the strict prohibition of the shogunate and smuggled Arita products from Nagasaki to India for sale, gaining a huge profit. In 1725, Jirozaemon was executed and Kan’emon committed suicide by seppuku. The fact was finally discovered in 1725 and Jirozaemon was executed, and Kan’emon committed seppuku and suicide.

In 1751 (Horeki 1), the number of certificates (called “meiyofuda”) for those engaged in the pottery business was increased from 180 to several more under the name of “higuchi meifuda. In the An’ei period (1772-81), a new kiln was built at Izumiyama to replenish the shortage of kilns.

The Saga Clan feared that the secret of the Arita pottery method would be passed on and imitated, which would affect the pottery industry in and outside of Arita, so they established even stricter regulations, especially for the brocade decoration method, which was the most secret. In those days, there were sixteen akae (red glaze) dealers in Arita. There were sixteen akae potters at that time, but the number is now limited to several dozen, and in particular, pigment blending methods were made to be handed down only to the head of the household. He finally escaped and traveled to other countries to teach the secrets of the Arita pottery method. The Saga Domain immediately dispatched its chief retainer, Kobayashi Dennai, to investigate his disappearance in various countries, and after several years, he was finally captured in Tobe, Iyo Province (Ehime Prefecture), and brought back to Japan, where he was punished by the national law and hanged on the Kodo Pass on the way between Arita and Imari. Before this, during the Manji period (1658-61), Goto Saijiro is said to have come from Kaga (Ishikawa Prefecture) to explore pottery techniques, and in 1797, Sato Ihei from Aizu (Fukushima Prefecture) came to Arita, pretending to be a servant of Kōdenji in Saga, to learn how to fire blue-and-white porcelain. In 1801, Kato Tamikichi of Owari Seto (Seto City) visited Arita, Mikawachi, and other areas to explore all the techniques of porcelain making. In view of this situation, the Saga Clan strictly forbade potters from other countries from entering the production area and restricted the sales market to Imari, so most of the products from Arita Uchisotoyama were shipped to other regions via Imari and came to be known as Imariyaki.

In 1790 (Kansei 2), Gengo Kitajima of Arita Akae-cho obtained a government license and traveled to Tsushima, where he was allowed to monopolize Korean ceramics and porcelain for Korean consumption by order of the feudal lord Mune. The monopoly contract was abolished when the system was reformed in 1871 (Meiji 4).

During the nights of Kyowa (1801-4) and Bunka (1804-18), a potter named Momota Tatsuju lived in Izumiyama. He studied the improvement of kiln stacking, and devised a method of stacking two levels of balance instead of the conventional flat stacking, which resulted in the firing of about twice as many pieces and made a remarkable contribution to the development of this industry. The reason why Arita’s pottery industry developed greatly between Bunsei and Tempo (1818-44), with a rapid increase in output and the production of exquisite pieces, was due to the emergence of prominent potters such as Fukami Otokichi in Izumiyama, Tsuji Kiheiji in Kamikouhei, Tashiro Hanjiro in Otaru, and Nanri Kaju in Shirakawa, and the competition of various techniques by Imaizumi Heibei in Akaemachi. The result is nothing else but a result of the competition of various techniques. Kiheiji Tsuji, in particular, invented Kyokushin-yaki porcelain, and the reputation of Arita-yaki porcelain was further enhanced through the production of clean and rich products. This was the heyday of Arita porcelain.

In 1860, Tashiro Monzaemon also opened a store in Nagasaki with an official license under the name of the British trade. In 1867, Marquis Kaso Nabeshima took the opportunity of the French Exposition to dispatch merchants led by Sano Tsunetami, a samurai of the domain, to introduce products and survey demand. This is said to have been the beginning of Arita’s overseas expansion.

In 1869 (Meiji 2), he invited Uzaburo Mizuhoya from Tokyo, who had returned to Japan after acquiring French paints, and also invited Moritaro Nishiyama, Takeji Fukamai, Tamesuke Otsuka, and Hikoshichi Mitsutake, all of whom were active in the Arita pottery industry, to Japan. The following year, a German, Wagner, was invited from Nagasaki to learn ceramic paints and coal firing. The application of cobalt and chromium spread throughout the country from this time. In the same year, Fukagawa Eizaemon tried out insulators for telegraphs, and at the 1873 Austrian Exposition, Kawahara Chujiro of Arita went to Austria and learned plaster molds and the method of painting with brocade oil, etc., which he taught to potters in various regions at the Kangyo Dormitory in Tokyo. In 1892, Iwataro Jojima first tried the use of copperplate glaze in imitation of the coal glaze of the Owari and Mino regions, and it was not until 1892 (25th year of the same period) that it was finally used by the general public and the old style of isles was introduced. The old style chairs were now limited to old-fashioned products.

In 1916, a monument was erected to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the discovery of Quanshan porcelain.

In 1970, the number of manufacturers was 117, the number of employees was 7074, and the annual production was 10.448 billion yen.

(History of Arita Ceramics, History of Arita, History of Japanese Ceramics in the Early Modern Period, History of Arita Porcelain Industry)