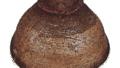

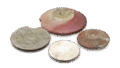

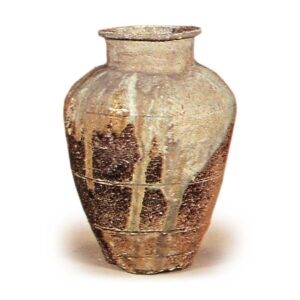

Tokonameyaki is produced in Tokoname City, Aichi Prefecture. There are several theories regarding the origin of Tokoname Pottery, including the Gyoki, Doji, Fujishiro, and Fushiki theories, but none of them are accurate. Old Tokoname ware from the Heian and Kamakura periods has been excavated from ruins in Hiroshima Prefecture and other areas from Shikoku to Aomori Prefecture, indicating that old Tokoname ware was widely distributed throughout the country. There are many stoneware jars and pots with natural or ash glaze running down the shoulders, all of which were made in a powerful and vigorous manner. There are also many tea bowls and tiles, but most of them seem to have been for religious or aristocratic use, not for ordinary daily use. In the Muromachi period (1333-1573), the kilns were built in holes dug in the ground. In the Muromachi period (1333-1573), teppo kilns were built above ground, and hard, black stoneware pots and jars, called makiyaki, were fired in great numbers. In the late Muromachi period (1336-1573), Mizuno Kanmono, a lord of Tokonose-Chime Castle, was a fashionable person who was friends with Sen no Rikyu, Tsuda Munenori, and Myokian Isao, and introduced many pieces of Tokoname ware to them, which is often mentioned in the tea ceremony chronicle by Tsuda Munenori. He later entered Tenryuji Temple and finally committed seppuku (ritual suicide). This is the reason why Tokoname ware did not appear in the tea ceremony during the Momoyama period. The world of tea ceremony ceramics opened up in Tokoname with the appearance of Tokoname Gonkosai during the Tenmei era (1781-19), and with the popularity of the tea ceremony from the Bunka era (1804-18), Tokoname ware entered the pottery age with the production of master potters such as Shiraogi, Tosen, and Chozo. In addition to Shinyaki, various types of pottery were produced, including Shiraogi’s red and black raku, Tosen’s ash glazed pieces, and Chozo’s white mud and algae glazes. Since then, many vermilion mud kyusu (teapots) have been produced, and at the same time, many other types of vermilion mud ware have been produced, creating a new field in Tokoname ware. In the early Meiji period (1868-1912), the English-style earthenware pipe was perfected, and large quantities of earthenware pipes began to be produced, which led to the production of new products one after another. In 1882, a Shinyaki rice-pounding mortar was produced, and radius earthenware pipes were also begun. In 1901, Akebono ware with a salt glaze was begun. Large-scale production of jars, wellsides, etc. was also flourishing, and earthenware pipes now accounted for more than half of the nation’s total production.

Various types of Shudo ware called “dragon rolls” were exported in large quantities to the U.S. Various types of telephones, dolls, ink bottles, and other items were produced, as well as braziers and flowerpots in large quantities. Tile and terra cotta production began in earnest in the Taisho period (1912-1926) and flourished greatly, reaching a total output of 488 million yen in 193 (1931). After World War II, sanitary ware production flourished, accounting for the majority of the nation’s production. Architectural ceramics such as tiles and mosaics, flower vases, flower basins, flowerpots, dolls, and red clay teapots were the most widely produced items, with an annual output of approximately 2 billion yen. About 10,000 people were employed in the ceramic industry. Tokoname ware is described in “Tokoname Kogyo Appendix,” “Kogei Shiryo,” “Kanko Zusetsu,” “Tokoname Ruishu,” “Nihon Tokoname Kogyo Shiryon,” and “Nihon Kogyo Shishi,” but since there are many inaccurate descriptions, this report is based on the findings of the Tokoname Kogyo Research Association.