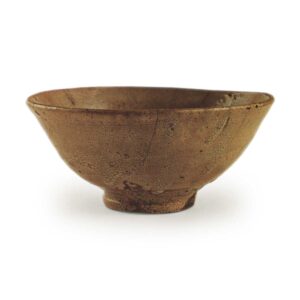

Collection: Fujita Museum of Art

Height: 6.0cm

Diameter: 13.3cm

Foot diameter: 4.7-4.9cm

Height: 0.8cm

This is a representative tea bowl of the Ido-te Konuki-iri (also known as Konohibite) style. The name Ogurayama is said to be a reference to the Shokado style, and the name is thought to have been given in reference to the beautiful glaze of this tea bowl, which resembles the autumn leaves of Mt.

Onuki-iri refers to fine cracks, and through the Ido-te style, cracks are considered to be one of the promises or highlights of the tea bowl. Regardless of whether it is a large or small well, if the glaze is thick, it will be called ara-nuki-ire, and if it is thin, it will be called ko-nuki-ire, but the small nuki-ire of wells that tea masters particularly like to use is not necessarily characterized only by the presence of fine cracks.

According to one tea book, Koido is not just a small shape, but also refers to something that looks small in terms of glaze or workmanship, and Ko-nukui is limited to Koido-te, and does not include Ko-nukui of Oido-te.

The definition of koido is rather vague, as you would expect from the tea ceremony, so it’s hard to get the gist of it, but you can get the general idea. The tea ceremony does not call the well-tempered ware koido simply because it has small cracks.

The Ogurayama has a loquat-colored glaze, and although it is thin, the marks of the potter’s wheel can be seen, and there are side handles. The foot ring is made to look like a bamboo joint, and there is a helmet-shaped ring inside the bottom. There are four slightly stylized five-pronged rings on the foot ring, and there are also four marks on the inside. In other words, it is a work that properly follows the basic rules of Iwate ware, and even if it lacks the dignity of the Oiwado period, it is a work with a refined glaze and a style that is appropriate for a thinly made piece, and it is very much worth seeing.

The fact that it was loved and inscribed by Shokado is also something that is most understandable, and it is an excellent piece with the subtle charm of the tea ceremony. The thin, light-weight style of the work is generally agreed to be of a later date than the Oido and Aoido styles, but the origin of the Koido style is of this type, and in that respect, it is good to agree that the tea masters first distinguished the Koido from the Oido.

Next, the fine cracks that cover the entire surface of the glaze are a characteristic that immediately catches the eye, and the fact that the tea masters singled out this point in particular to recommend the small crackle ware is also evidence of the subtlety of their aesthetic sensibilities. When you consider the conditions of the thin, hard-fired clay body, which contains less iron than Oido ware, it is easy to understand why this type of ware is prone to tiny cracks.

The term “kobinuri” is used to refer to the fine cracks that are even finer than those of Oido and other types of ware, and the characteristics of kobinuri are clearly pointed out. However, in the case of Ogurayama, the glaze is slightly rough and bluish in places where the glaze has run or pooled, and the glaze also shows variation in the areas where it has been brushed on, so it creates a scene that is truly captivating.

Inner box, black lacquer, gold powder lettering, attributed to Shokado “Ogurayama

It is said to have been passed down from Tsuda Kyubei, a lumber dealer in Osaka known as Omiya, and later passed down to the Fujita family, and became part of the Fujita Art Museum collection when the museum was established.