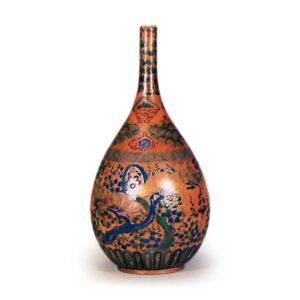

Kiyomizuyaki is ceramics produced in the vicinity of Gojozaka in Kiyomizu, Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto. The origin of Kiyomizu-yaki is said to be long ago, but the pottery industry began to flourish when Nonomura Ninsei opened a kiln in this area around 1624-44, and porcelain as we know it today was produced in imitation of Arita-yaki around Bunka period (1804-8). The products, including tea sets, sake cups, plates, bowls, bowls, vases, and incense burners, are all highly prized for their elegance and grace. Shigaraki clay, Mikumo clay, amakusa stone, and chairs were used as raw materials in the past, but recently frog clay, feldspar, silica stone, and limestone have been used. Hand-thrown potter’s wheels and plaster molds are used in parallel to form vessels, and there are three types of kilns: ascent kilns, unglazed kilns, and nishikgama kilns. Ascending kilns are so-called “kilns” and are much smaller than the kilns in Arita and Seto.

Terokuro [History] As with Awata ceramics, the details of the origin of terokuro are unknown, but according to an inscription by a potter, it dates back to the distant Tenpyo period (729-49), when the monk Gyoki made earthenware at Chawanzaka, Seikanji Village, Atago County (Seikanji, Higashiyama Ward) under the orders of Emperor Shomu. The site still contains the ancient ruins of this pottery. There are still traces of the earthenware production in the area. During the Enryaku era (782-806) of Emperor Kanmu, there was a tile maker in Takagamine, Rakuhoku, who made heki kawara (blue tiles) for Heian Castle in this area. In the Genryaku era (1184-5) of Emperor Toba, he moved his kiln to Fukakusa in the southern part of Rakunan and exclusively produced pottery. However, his products were coarse and unglazed, and were commonly referred to as pottery. Later, during the Shoan Era (1299-1302), during the reign of Emperor Fushimi, a priest at Nanzenji Temple named Kyosho, who was well versed in pottery making, happened to teach Fukakusa tile makers the technique. From this time on, tile makers in Fukakusa frequently made pottery using this method. However, none of the ceramics were produced because the method of fire strength was still unclear. During the Houtoku era (1449-52) of Emperor Go-Hanazono, a man named Otowaya Kuroemon lived in Seikanji Village, Atago County. He discovered the ruins of Chawanzaka in Seikanji Village and moved his kiln to Fukakusa, where he produced pottery. His products were not solid, but they were close to perfect. He took pains to improve on the old Fukakusa method and finally discovered glazing. From Tensho to Keicho period (1573-1615), master potters such as Masayi, Manyemon, Sohaku, Rokuzaemon, Sozo, Genzuke, and Genjuro were produced and engaged in the pottery business. They lived in Otowa, Seikanji, Komatsudani, and Shimizu, and their names were Otowa, Otowaya, and Maruya. At the end of Keicho, they moved their kilns to Gojozaka. It is said that he was ordered by the government office of the time to move to this location because it was close to the mausoleum of Prince Toyo at Amidagamine and the smoke from the kiln always polluted the area. At this time, a potter named Kyubei Chawan-ya invented the technique of painting, which finally led to the application of gold, red, blue, and other colors. However, Kyubei is said to have been a merchant in Awata ware and a craftsman in Kiyomizu ware, and it is not known which is correct. It is thought that he was a craftsman who also worked as a merchant. Later, during the Kan’ei period (1624-44), Nonomura Seiwemon (Ninsei) built a kiln in Sanneizaka, Kiyomizu, and began to produce Gat ware. In addition, Ogata Kenzan produced a variety of wares that were highly praised. In particular, during the Bunka period (1804-8), Aoki Kime studied Chinese ceramic techniques and actively produced elegant wares, and also promoted the national interest by translating “Tou-setsu” into Japanese. As a result, Kiyomizu’s pottery production improved again, and the reputation of the Kyoto kilns spread.

At this time, such craftsmen as Takahashi Michihachi (Niami), Shimizu Rokubei, Seifu Yohei, Wake Heikichi (Kame-Tei), Ogata Shuhei, and Mizukoshi Yosanbei emerged, all of whom were renowned for their work.

Heikichi Wake and Shuhei Ogata, in particular, worked together to improve blue-and-white porcelain, and had Heikichi’s student Kumakichi study the methods of porcelain making in various regions. Kumakichi traveled around the country and finally learned the secret methods of Hizen Arita stone porcelain, which he used to produce his own products. Takahashi Dohachi, Seifu Yohei, Shimizu Rokubei, and others refined the technique, and finally produced gold brocade Hiyoro-ga and other works of art, opening the way for exporting them widely overseas. According to the above history, the development of the pottery industry in this area seems to have been mainly through the various crafts during the Eisho (1504-21), Keicho (1596-1615), Kan’ei (1624-44), and Bunka (1804-18) eras, and compared to Awata-yaki, although the originators of the pottery in both areas are the same, they have developed at different rates. Compared to Awata ware, both regions have the same originator, but the speed of development differs between the two. In other words, while Awata pottery was first developed in the Keicho period, it was already developed in the Eisho period, which was 93 years before Awata.

There is no way to know whether this is true or not, or whether the difference is due to the sparseness of the oral inscriptions in the two areas. (History of Ceramics in Early Modern Japan)