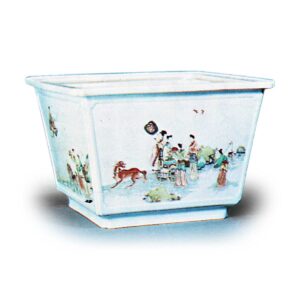

An official kiln of the Kangxi period (1662-1722) of the Qing dynasty in China.

Abbreviated as Kangxi kiln. The Kangxi kilns were already in operation in Jingdezhen during the Shunji period (16461), when the Ming dynasty fell and the Qing dynasty took over. However, little is known about the activities of the arsenal in the early Kangxi period. However, a kiln called “Rang Kiln” had a reputation as a specialty of the Kang kiln. It is said to have been fired by Rang Tingji, who was governor of Jiangxi and Jiangnan provinces for about four years from 1665 (Kangxi IV) to 1668 (Kangxi VII). In addition, there is almost no other evidence of his involvement in the early years of Kangxi. However, it does appear that in 1671 (same year as the first), he dedicated ritual vessels and sent them to the capital.

However, in 1673, a rebellion by Wu Sangui, governor of Yunnan, destroyed the arsenal, followed by uprisings in Taiwan, Fujian, and other areas, and the kiln business was discontinued. In September 1680, the first pottery production was started, and Tang Tongchujiro Zhongzu Tingpil and Li Tingxi were dispatched to Jingdezhen to stay at the pottery to supervise the pottery production. The system had been to summon skilled potters from the provinces under the jurisdiction of Raoju (Jiangxi Province) and force them to engage in pottery making, but this was changed to a system of free labor, and potters were summoned to supply materials each time pottery making was conducted. The amount to be paid was to be paid when it was due according to the market price at that time. In addition, the cost of transporting porcelain fired in the past was to be borne by each locality, but was abolished and all payments were to be made by the government. In addition, kiln work was removed from the administrative duties of local officials so that they could concentrate on their own administrative duties. As a result of these changes, the kiln work of the imperial court inevitably continued to improve and progress. Next, in 1682 (Kangxi 21), the Ministry of Works appointed Joint Chief Joint Chief Joint Chief of the Department of Construction and had him manage the Gogi. The kilns managed by the Joint O-seon and their vessels were called Joint Kiln. It is known from the fact that Tang Ying’s “Feng Hua Shen Dian” says, “When the Joint Governors supervised the pottery of the Joint Governors, every time I saw the God’s finger painting on the fire of the kiln, the vessel was refined. However, it is not clear in what way he was excellent because of the lack of literature, but we can almost guess about the joint kiln by the following description. The following description is written in the “Jingdezhen Ceramic Record”: “The clay of joints made by Joint O-Chien is fat and thin, and it is complete with various colors.

There are four types of clay: snake skin green, sea-bass yellow, jicui yellow, and speckled. The four types of clay are snakeskin green, sea-bass fish yellow, gicui yellow, and speckled, and the four types of greenish-green, greenish-purple, greenish-green, red, and blue are also beautiful. Later, there was a Tang kiln, and its glaze colors are still followed. Other than the above, there is little else known about the Kangxi arsenal in Chinese literature. However, there are two letters dated 1712 (Kangxi 51) and 1722 (Kangxi 61) written by Père d’Entrecoeur, a Jesuit missionary who lived in Raoju at the end of the Kangxi period, which shed a great light on the Jingdezhen kiln industry at this time. The Kangxi ware is so varied, including blue-and-white, colorful, and monochromatic, that it is difficult to describe them all in detail. The clay is well selected and pure, and the glaze is usually clean and pure white with a faint light green tinge, like that of duoliping or jade. The Kangxi glazes are not only wet, but also not uncommonly close to those of the Ming dynasty. Although the blue flowers are less deep than those of the Ming dynasty, the refined blue color of the finest pieces is clear and transparent, and was especially admired by the English. Even at the beginning of this century, the famous ice plum cans, for example, brought tens of thousands of dollars per piece. However, such fine wares are few and far between, and most of them are more or less darkly colored. In other words, Kangxi blue-and-white porcelain is gloomy and gives a cold feeling in combination with its glaze color. It is said that the tradition of underglaze red in colorful porcelain ceased in the Ming dynasty, but it was revived in the Kangxi period. However, the most beautiful and successful examples were produced in the late Kangxi period and were limited to small vessels. The most remarkable type of colorful porcelain is sancai or sosancai, in which the base colors are green, yellow, black, etc. Westerners are not so fond of sancai. Westerners highly value sansai, and those with a black background are called “black hawthorne,” for which they lavishly spend large sums of money. The five-color or red glazes of the Yongzheng and Qianlong periods (1723-1955) were less delicate and exquisite, but many of the paintings had a more elegant elegance in their simple technique, which is why they were called kangcai and greatly cherished by connoisseurs. The famous Rang kiln is famous for its monochrome glazes. It is said that the pieces produced before the middle of the Kangxi period were excellent, while those produced in the late Kangxi period were already of declining quality. However, what is the basis for this theory? It may be due to the fact that Rang Ting-chi was governor of this region at the beginning of Kangxi, but there is still room for further research. Peach blossom red and shohin green are also known to have come from this period. In 1677 (Kangxi 16), at the suggestion of Chang Qi-nong, an euphonious decree of the Kangxi government, the writing of annual annotations was forbidden, but by the end of the Kangxi period, annotations were being used again. (The writing of annals was prohibited by the recommendation of Chang Qi-nong, the head of the euphonic order, in 1677.)