Earthenware decorated with decorative elements by coloring. Also called “colored earthenware. Some earthenware vessels were decorated with engraved lines, one of the decorative techniques used on earthenware, and the engraved lines were filled with white clay after firing. Some people argue that it is less confusing to call earthenware with the entire surface painted in a single color “colored earthenware” and earthenware with patterns “painted earthenware,” but the history of research on this type of earthenware shows that the same type of earthenware has been called both “colored earthenware” and “painted earthenware. The name “colored earthenware” is now widely used. In the case of Chinese pottery, it is also called colored pottery. Typical colored earthenware and many other types of colored earthenware were fired after the molding stage was completed and the earthenware had been dried, then colored. Colors applied after firing are easily lost and often discolored because the coloring material is not adhered due to the high temperature. Colors are used in some cases only one color and in others more than one color. The choice of color itself, like the pattern, is recognized as one of the characteristics of each culture. In general, geometric patterns were most commonly used, but there is a wide variety of patterns including botanical, animal, and human figures, scenes of human activities such as hunting and navigation, and a combination of some of the above patterns. Moreover, while it is easy to assume that these patterns are simply a combination of geometric patterns, detailed typological research, which is the basis of archaeological research methods, often leads to figurative patterns, which are not so easy to classify. For example, on Samarra earthenware from Mesopotamia, a row of dancing women is transformed into a row of jellyfish, or four goats arranged in four directions into a shape like the tip of a wheat ear, or a series of bull heads into a chain. The process of change from a fish design to a continuous triangular design is also evident in the colored pottery. Even if the origin of the individual patterns has been determined, the question of why such patterns were used to decorate the pottery remains unanswered. The simplest of the theories proposed so far is that of imitation, in which the pottery itself was made by imitating woven baskets, wooden vessels, or stone vessels. The fact that the pottery made to resemble woven baskets has geometric patterns, that the high cups excavated from Crete imitate wooden cups and show the grain of the wood in colors, and that the stripes on Egyptian and Cretan stone vessels are faithfully represented on the pottery are well-known examples of this theory. However, this theory of imitation cannot explain the realistic representation of botanical and animal patterns. This is where the idea of recognizing a magical meaning in the various representations of Toretto and others comes in. The patterns on the right are thought to have been created by potters who believed that the weave, grain, and stone stripes on the pottery had the effect of making the pottery unbreakable. In a completely different interpretation, Wilhelm Woehringer, in his commentary on geometrical patterns, wrote: “Disturbed and anxious by life, primitive man seeks inanimate objects because they are the most suitable for the creation (Werden). He thinks that this is “a plane geometrical or stereogeometrical figure” (Isamu Nakano, “Gothic Art Forms”). Alois Riegl argues as follows. Alois Riegl also asserts, “Once a botanical pattern is adopted as an ornamental form, there is a rush to transform it (for example, the lotus) into a geometric pattern. This is because it is convenient to bring about both a geometrical composition through technical processing and an artistic use of the shape. Furthermore, animal (human) figures must often have been transplanted into geometric forms before botanical figures. Such transplants were not the result of a lack of ability to create something better. This is amply demonstrated by the aforementioned caveman’s obvious efforts to take animal (human) figures from real phenomena and represent them as realistically as possible in shadow puppets. Therefore, the geometric formalization of human and animal figures was originally a conscious copying of these figures into line figures, just as if geometric patterns were a conscious combination of lines based on left-right symmetry and rhythmic rules. The recognition of geometric patterns on colored earthenware began when Alexander Conze analyzed Classical Greek pottery and established the “geometric style” as the earliest phase (1870). Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations in Troya revealed Mycenaean pottery with painted designs and pottery with geometric patterns, but with engraved lines, in the lower layers, confirming that the origin of the geometric patterns dates back to an even older period. From the end of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century, pottery with colored designs was discovered at Diospolis Parva in Egypt, Susa in Iran, and Anau in West Turkestan, demonstrating the development of pottery production techniques in prehistoric times.

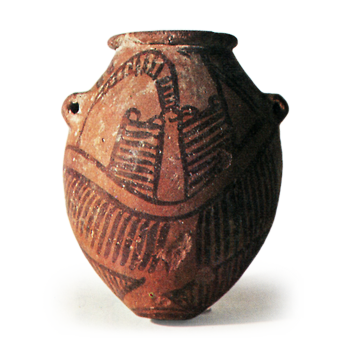

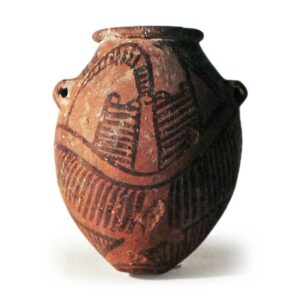

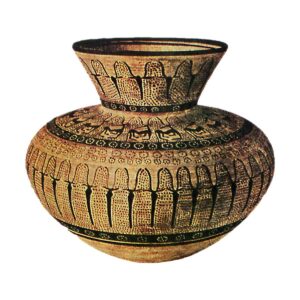

Around 1920, when colored earthenware was discovered at Eridu and Ur, the centers of Sumerian civilization, the lineage of these colored earthenware became an issue in relation to the Sumerian theory of origins, and many researchers participated in this debate. Among them, Stefan Langdon’s hypothesis prevailed. The makers of painted earthenware crossed the Iranian Plateau from Anau in Central Asia, one group reached Egypt from Syria before the 4th millennium B.C., and a later group crossed the Iranian Plateau and reached Mesopotamia before the 5th millennium B.C. The Sumerians, who were the first to produce painted earthenware, were the first to produce painted earthenware in the Middle East. This group is said to be the Sumerians. In the 1920s, Henry Frankfort conducted a comprehensive study of the pottery, criticizing the phylogenetic view that linked the existence of colored pottery to the migration of people from one region to another, and clearly distinguishing between the similarities and uniqueness of colored pottery from one region to another. He clearly distinguished between the similarities and uniqueness of the various regions, and liberated the colored earthenware from the prejudice that it was the product of a specific race. The users of painted earthenware did not use only painted earthenware as earthenware, but rather, painted earthenware accounted for a small percentage of the earthenware used in daily life. According to Tsuboi Kiyotsuki, the ratio of pottery excavated from the pit at the Xiyin Village site in Shanxi Province, China, is 163% painted pottery, 11.6% black pottery (black or gray, different from so-called black pottery), 5.6% pointed bottom jars, and 31.3% rough pottery. The painted pottery forms are containers for serving or storing objects such as bowls, jars, and high cups, and since redware is also found in this type of vessel, it has been pointed out that painted pottery existed as a special type of container (Sekai china zenshu, 8). The percentage of painted earthenware found at any site to the total pottery excavated is not large. If this fact is confirmed, we can obtain important information about prehistoric times and ancient peoples from colored earthenware. Furthermore, by comparing the patterns of colored earthenware from different regions, we have more data than other coarse earthenware on cultural influences and sometimes on the migration of specific groups of people. This is because The earliest period colored pottery is currently found in an area spanning western Iran and northeastern Iraq. It is thought to date from the late 7th to early 6th millennium B.C.E., a period in the Neolithic stratum that somewhat delays the appearance of pottery, and consists of bowl-shaped earthenware decorated with horizontal zigzag and lattice patterns in bengala. Excavated from the Jarmo site at about the same period, the Hassouna and Samarra style of colored earthenware gave rise to the most developed and beautiful Halaf style of earthenware in West Asia. In South Mesopotamia, red or grayish-black earthenware became popular during the Uruk period, and colored earthenware declined once, but was revived during the Gemudet Nasr period and continued for about a thousand years until it was almost completely discontinued around the second millennium B.C. The painted earthenware excavated from Susa, which became famous under the name of the Susa I and II styles, was later subdivided into four periods, and recently painted earthenware that preceded the Susa I style has been identified, showing that the changes in Mesopotamian painted earthenware correspond to those in Mesopotamia. The technique of Mesopotamian painted earthenware was also introduced to Syria, Palestine, Cyprus, and the Anatolian plateau, where it was produced until much later. The earliest Egyptian pottery with painted designs is a woven basket with engraved designs and filled with white clay, excavated from Tasa. It is estimated to date to the 5th millennium B.C., but it probably originated independently of the Mesopotamian painted earthenware. In Egypt, black earthenware with geometric patterns made of white clay became popular in the Amur period, and in the following Gerze period, in addition to earthenware decorated with geometric patterns, distinctive earthenware with boat motifs painted in red and purple was produced. In Egypt, the use of painted earthenware in the First and Second Dynasties was reduced to simple geometric patterns, but a considerable amount of painted earthenware from Crete, Syria, and Palestine was brought into the country. In Greece, there were painted earthenware with geometric patterns such as rhombic and triangular zigzag patterns from the Neolithic period of the Sesklo culture. Earthenware of the Dimini culture of the late 3rd millennium B.C.E. has a large number of curved patterns, especially whorl patterns. Under the influence of these colored earthenware vessels, Neolithic earthenware vessels with colored designs from East Europe, Italy, and other regions emerged. The famous colored earthenware from Tripoliæ belongs to this lineage.

In Crete, the Kamalez style of pottery appeared in the First Palace Period of the early 2nd millennium BCE. It is a graceful piece of pottery with white, red, and yellow painted flowers and plants with curved patterns on a black background. During the Second Palace period, it became fashionable to depict plants and marine animals realistically in dark monochromatic colors on a light ground. The Mycenaean style of pottery was created by mixing Cretan and Greek pottery. The color of the earthenware was black or brown on a light ground, and it was painted with geometrical patterns as well as fully patterned animal and human figures. This led to the Greek geometric style. Eventually, the black-painted style, which is thought to be the result of the unusual development of colored earthenware from the Easternized style, was produced, followed by the red-painted style and the white-ground style. During the heyday of Greek pottery, the Hallstatt culture, which belonged to the Iron Age, flourished in the center of Europe north of the Alps, followed by the Latene culture, which also produced colored earthenware during this period. The technique of decorating earthenware with colored designs, which spread from Mesopotamia to the east, spread from the Iranian plateau to the surrounding areas. In the north, from the Turkmenian Joithun culture to the Anau III culture, the use of colored earthenware became very popular. Based on this, colored earthenware with many plant and animal patterns characteristic of the Indus civilization was born, and it spread to Central India. The technique of applying colored patterns, which probably spread from Central Asia to China, became painted pottery in the Hwang Ho basin and further spread to the surrounding areas. Painted ceramics have also been discovered in Taiwan. Although the genealogical relationship is not clear, there is also a type of Korean comb-shaped earthenware with a reddish-painted pattern that has left part of the engraved line band without engraving, and another type of earthenware called tan-nurimaben earthenware is also known. In Japan, some Jomon-style earthenware is painted in red, and Yayoi earthenware is either covered entirely in red or decorated with painted patterns. In both North and South America, many types of colored earthenware are known, but they probably developed independently in a completely different lineage from the colored earthenware of the Old Continent.