A potter from Kyoto. Along with Ninsei and Kenzan, he is considered one of the three greatest master potters in Japan. His family name was Aoki, his childhood name was 88, and he later changed his name to Sahei, after his father. His alias is KIYASABEI, or KISHA SAHEI, or SABEI or SAHEI. His characters are Seirai. His family names include Kume, Kuju-in, Hyakuroku-sanjin kojikan, and Teiunro.

He was born in Kyoto in 1767.

His ancestors originated in Mino Province (Gifu Prefecture). His father, Sahei, was originally from Owari (Aichi Prefecture), but later moved to Gion Shinchi Nawate-cho, Gion, Kyoto, where he ran a teahouse called Kiya. As a child, Kibei was influenced by the famous seal engraver and calligrapher Ko Fuyo (1784-, died in Tenmei 4, aged 63, Kibei was 18 at the time).

Later, he became interested in old coins and minted them himself. However, it was not until he visited Kimura Kenkado in Osaka and read the book “Tao Xiong” by Zhu Kasatei, a Qing Dynasty Chinese potter, which was included in his new book “Longwei Secretary,” that he decided to make pottery his life’s work. He was 30 years old when he started his career as a potter. According to an article by Tanomura Takeda, his teacher in the art of pottery was Yegawa.

According to the Unrin-in Family Tree, the 11th Zou (Hozan) was also Kigome’s teacher. Generally speaking, Kume may have learned porcelain from Yegawa and pottery from Bunzo. Kigome’s genius emerged within a few years, and his fame spread throughout Kyoto and Osaka. Then, in 1808, Tokugawa Chiho, Marquis of Kishu, heard of Kime’s fame and invited him to Wakayama. It was in this year that Zuishibayaki was founded, and Kikumai may have followed his kiln. It is said that he was given the silver seal of Teiunro at that time, but there is another theory. In 1805, he was ordered to work at the Awata Palace of Seiren-in Palace, and in August 1806, on the advice of Kameda Tsuruyama, he went to Kanazawa in Kaga Province, tried his hand at Utatsuyama, and returned to Tokyo to work on a doll made by Yoneki Shirasaku. In 1807, he returned to the same place and established the Kasuga-yama Kiln. He died on May 15, 1833 at the age of 67. Kikume was a versatile potter by nature, and he was also a family man in the field of painting. He was associated with the writers and artists of the time, such as Sanyo, Takeda, Kotake, and Palmyra, and his knowledge of Chinese studies was considerable, making him more than a mere potter.

He was not a mere potter, but a scholar of the Chinese language, and the inscription on his tombstone, which was also written by Kotake, includes the words of Mokume, a literate potter. He was painstakingly diligent in his work, and it is said that he became deaf in middle age because he put his ear to the kiln when firing to keep an eye on the fire. The most important thing that cannot be overlooked is that the “pottery” is a “treasure house”. The most important thing that cannot be overlooked is the reprinting of the “Tōhsetsu. The “Tōhsetsu” was the book that introduced Kikume to the pottery business, and it has long been the standard for Kikume’s pottery work. He purchased a copy at his own expense and reprinted it in 1804. However, he later realized that there were many errors in this edition and intended to correct them, but he died without completing the revision project. This book was published by his son Shukichi in 1835 (Tempo 6), after Kigome’s death. It was published by his son Shukichi in 1835, 31 years after Kigome’s death, with a foreword by Sanyo Rai in 1827.

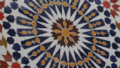

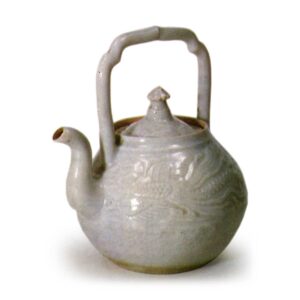

The atmosphere of the literati society at that time made it possible to comment that Kume generally devoted his life to imitating Chinese porcelain, with little regard for ceramics. The main focus of the pottery was the production of sencha wares, which were in vogue at the time. The following is a brief description of each type: (1) This is one of the best examples of Namban copying by Kime, with a large number of kyusu (teapots). The shape is a sold tea bowl, and if you stand it with your hand on its axis, it will stand safely without falling over. The potter’s wheel turns smoothly, the spatula is lean, and the clay is pleasantly firm. (The shape of the upper part is octagonal, and the lower part is usually circular. However, because it is a katagemono, there are many forgeries. (3) Copies of kyusu are of the same type, but there are not only kyusu but also sencha bowls, incense containers, and various other types. The forms are also varied and highly variable. Kigome’s copy of kojiki is similar to Eiraku’s, but Kigome’s has a much older color due to its glaze and other factors. Kigome’s kyusui has a much older color due to its glaze and other factors. The most common type of kyusu made of kyusu is araiso. (It is said that the white porcelain blue and white flowers of Kume’s blue and white porcelain were the first to be produced in Kyoto, and that they had already been attempted at the Kasuga-yama kiln and other kilns before the creation of the blue and white porcelain of Dohachi in 1812 (Bunka 9). There are many varieties, including incense containers, tea containers, teacups, tea cups, leaf tea pots, kyusu (teapots), and sencha (green tea) bowls. Kime is known for his painting techniques, and his paintings on dyed cloth are light, delicate, and bold, with an elegance that is difficult to describe. The underglaze blue enamel paintings of Kawamoto Jihei, a later Seto potter, are said to resemble Kikumai’s work so much that they are often treated as if they had Kikumai’s mark. (V) Many celadon porcelain pieces have a strong Shichikan style, but there are also doll hands, and the handles are heavy and very good work. Many of the celadon porcelains seem to have no special mark. (VI) There are not many red glaze works. (VI) There are not many red glaze works, but there are some in the style of Yuekawa, Hyakko hand, Hyakuro hand, and so on. The most famous example is a sencha (green tea) bowl with a tea poem written on it in blue vitreous ink. (7) There are a small number of Joseon copies, Mishimate, Gohon copies, and others. (8) There are few examples of gold brocade. The red glaze layer is extremely thin, but the color appears deep and graceful. (9) There are few copies of the Insei style. The technique is skillful, but the pieces have a Chinese flavor. (1) There are some excellent pieces such as sandware and white mud wind furnaces. Many of them are carved with plum and moon in reverse on the wind gate. The three claws are particularly wide, and the upper part of the hole is gradually narrowed, which are characteristic of Kume’s furnaces. Other examples include Sung Hu-roku and Dutch copies, but none of them are known to be in Masanare. Generally speaking, Kume’s kyusu is characterized by the skillful use of the plucking, mouth construction, and handles, which give the viewer the impression that the entire piece is alive. The inscriptions of Kume’s kyusu are listed separately, but see the section on the inscriptions of vessels made at the “Kasuga-yama Kiln”.

Kigome’s son Shukichi died prematurely in 1843 at the age of 18, and his grandson Kogome died around the middle of the Meiji period. The “Sho of Kami Okudono” was written by Kigome in 1820 to Matsudaira Noritake of Okudono, Mikawa Province (Okudono-cho, Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture), to accompany the “Tōshi” (Ceramic Discourse), which he had copied. This section is based largely on Wakimoto Rakunoken’s “Heian Meito Den” (Biography of Heian Meito).