The Yayoi Shiki pottery is a type of prehistoric pottery from Japan, first excavated in 1884 in Yayoi-cho, Mukogaoka, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, and recognized as being different from the previously known Jomon pottery. This period was called the Yayoi period. During this period, rice paddy farming, the production and use of metal (iron and bronze) tools, and weaving techniques using looms were initiated due to continental influences. However, the traditions from the Jomon period are also strongly handed down. Yayoi earthenware is an extension of Jomon earthenware, with no decisive technological innovations. The same is true of the transition from Yayoi earthenware to its successor, the earthenware of the Doji period. Therefore, in some areas, the distinction between the last Jomon pottery and the oldest Yayoi pottery, and between the last Yayoi pottery and the oldest earthenware, remains unresolved.

There are two different views on the extent of the distribution of Yayoi pottery, and thus the extent of the Yayoi culture: theory A considers the northern Tohoku region to be an area where rice cultivation was not possible, similar to Hokkaido, and the area is considered a continuation of the Jomon culture based on fishing and gathering. Theory A proposes that these artifacts were transported from the Yayoi culture. The B theory, on the other hand, accepts these as evidence of rice cultivation and believes that the Yayoi culture extended to the northern tip of Honshu. In this case, although there are many similarities between the northern Tohoku region and Hokkaido in terms of pottery, Hokkaido alone is considered to be a region of the Continuing Jomon culture. Looking south, however, the Yayoi culture extends to the Satsunan Islands. Although the pottery itself was brought to Okinawa, it is safe to say that Okinawa is outside of the Yayoi culture.

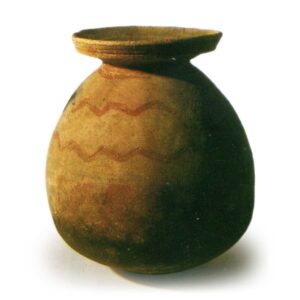

The Yayoi earthenware types include jars, pots, bowls, and high cup bases. Jars are spherical, long-handled, or flattened vessels with a narrow neck and a widened mouth rim. The majority of these vessels have horizontal rims, with large wavy protrusions or undulations being extremely rare. This is common to vessels other than jars, and is a conspicuous difference between Yayoi earthenware and Jomon earthenware. Jars with the neck and above cut off are called “no-neck” jars. In addition, jars are classified as narrow-necked, long-necked, or short-necked, depending on the characteristics of the shape of each part. Jars range in height from a few centimeters to over a meter. Jars are the most commonly decorated type of pottery. The main use of jars is for storage, and there are examples of jars filled with peaches (Karako Site, Nara Prefecture) and shells (Uryudo Site, Osaka Prefecture). However, there is also an example of a shell bracelet (Kumano Site, Hyogo Prefecture), indicating that the jar was sometimes used to store items other than food. It is desirable to put a lid on the jar in order for it to serve completely as a container. Some jars are accompanied by lids made as earthenware. It was also common to make small holes in the rim of the jar and in the lid, thread strings through them, and tie them together to seal the jar. Another type of liquid-filled jar is mizusagatate earthenware (Kinki and Sanyo). The side with the handle is lower than the rest of the vessel, and the mouth rim of the side with the handle is slightly cut off.

When the four fingers below the forefinger were used to hold the handle, the thumb was placed on this part of the mouth rim to tilt the vessel. Many jug-shaped earthenware vessels have soot on the surface, indicating that they were heated over a fire. Jars with spouts are also rare. There is also a type of jar that took the form of a pot but was used exclusively for boiling and cooking (Middle Kinki period). These are not very decorative. In addition, jars were often converted into coffins for the burial of fetuses and infants (壺棺). In eastern Japan, jars were also used mainly for reinterment, that is, to dig up and re-bury an adult buried with only the bones left. It is said that jars with facial expressions were made especially for these reinterment graves.

There are other jars that seem to have been made especially for ritual use. The jar is a deep earthenware vessel with a large opening in the shape of an inverted bell. In western Japan, most jars are unmarked or poorly decorated, but in eastern Japan, many are decorated. Medium-sized pots of around 30 cm or smaller were used for boiling and cooking, similar to modern pots and pans, and many of them are covered with soot. The lid of a jar protruded slightly beyond the mouth of the jar when it was put on, so soot adhered only to the outer edge of the inner surface of the jar. The center of the bottom of medium-sized jars often has a perforation about one centimeter in diameter. This jar with a perforated bottom is said to be a steamer, in other words. An upper jar with a perforated bottom is placed on top of the lower jar filled with water, and rice is placed on a sheet of rice flour inside the jar. The upper jar is then covered with a lid and a fire is lit to steam the rice. On the other hand, there are also many examples of pots and jars with inner surfaces to keep rice from burning, which confirms that there was a method of cooking rice. Large jars over 30 cm high are presumed to have been used mainly as water jars. Large jars do not have lids, and there are few cases of soot on them. In the Kitakyushu region, oversized jars were also used as burial coffins. Many of them exceeded one meter in height.

Bowls are earthenware vessels whose height does not reach the diameter of the mouth rim. A high cup is an earthenware vessel with a bowl-shaped cup placed on a foot. Many of these earthenware vessels are used for decoration. Many Yayoi earthenware vessels have a footstool. There are two types of Yayoi earthenware: one in which the footstool is removed and the other in which it does not exist. It is also possible to refer to only the latter as high cups and the others as bowls with pedestals, jars with pedestals, etc. Bowls and cups are serving vessels, equivalent to modern plates. In addition to being used as general tableware, cups and earthenware with a stand were often used in rituals. The foot of the high cups and earthenware with a pedestal is a stand. These are also strongly ritualistic in character. Some earthenware vessels were made by placing other types of vessels on top of the base and then making them into a single vessel. A semi-domed lid was attached to the top of the bowl (Late Period). Its use is unknown. Another special type of earthenware is the octopus pot. It is small (less than 10 cm), has a hole for a cord, and is assumed to have been used for collecting octopuses. What is unique about Yayoi earthenware compared to Jomon earthenware is the relatively clear functional differentiation between jars, pots, bowls, and cups, and the use of all of these in a single set. In the study of Yayoi culture, this set of tableware is called a style, and its transition is pursued by region, grouping it into three periods: Early, Middle, and Late. For example, the Kinki region is divided into three periods: Early Period (Form I), Middle Period (Forms II, III, and Yayoi Pottery N), and Late Period (Form V). In western Japan, stone tools almost uniformly disappear after the Middle Period, and the Late Period is the genuine Iron Age. The composition of the styles differs from period to period and from region to region. In the early period, high cups were rare, and jars and pots were predominant, with a ratio of approximately four to six. In the mid-middle period, the high cup was promoted to one of the main types of vessels in the style composition, with jars, pots, and high cups in the same proportion. In western Japan, the differentiation of function and composition of these types of vessels is fairly standardized, whereas in eastern Japan, this is less clear, and the vessels are displayed in a more traditional manner.

The interpretation that the potter’s wheel was used in the production of Yayoi earthenware is now a thing of the past. The basic production technique is the same as that used for Jomon earthenware, i.e., molding by piling up clay strips. However, in the Kinai region, the Chugoku and Shikoku regions to the west, and parts of the Chubu region to the east, a type of turntable was used for forming, adjusting, and decorating earthenware from near the end of the Early to the end of the Middle Ages. Although the structure is not known, the most recent examples, which date to the end of the middle period, show that the concave line patterns (a type of sunken line pattern applied using a rotating motion) rarely show discrepancies between the beginning and the end of the application, indicating that the stand rotated correctly. In a rare case where the start and end of the applied decoration is known, there is an earthenware vessel of about 20 cm in diameter with an excessively large overlap of 10 cm, which shows a part of the actual rotation process. In the Kinai region, the middle period comb patterns such as linear, wavy, and bamboo screen patterns were all drawn using a rotary motion, and the comb tool was not removed from the surface of the vessel during the process of drawing, but instead traveled around the entire circumference of the vessel. In contrast, the comb patterns on pottery from the Chubu region and eastward and Kyushu region are all drawn without using rotary motion, and the linear and wavy patterns often have several discontinuous areas around the entire circumference of the pottery. Another somewhat unique molding technique for Yayoi earthenware is the special production method used in the Kinai region, which was adopted for the production of high cups and other earthenware with bases only in the latter half of the Middle Ages. Normally, earthenware with a stand is made either by making the stand and then adding the upper part, or by adding the stand to the body that has already been made. In this period, however, a special molding method was used, in which the outer part of the upper part was first made continuously from the base, and then a disk was filled in to form the bottom of the upper body. By the end of the Middle Ages, this method was used in Kitakyushu and along the coast of Ise Bay. In addition, I would like to mention the brushwork and polishing techniques used to adjust Yayoi earthenware, which began with the Yayoi earthenware and continued with the earthenware of the Doji period. It should be noted that brushwork in archaeology differs from the terminology used by potters. Recent research has shown that this is the result of stroking the surface of an earthenware vessel with a splitting board, which leaves numerous fine parallel lines in the undulations of the grain. Polishing is the process of polishing the surface of a vessel to make it denser, and the result is that the polished surface is made up of small, elongated surfaces instead of round stones. The firing temperature of Yayoi earthenware is approximately 500-600 degrees Celsius, which is not much different from that of Jomon earthenware.

Yayoi earthenware often has black patches on the center of the body (or one of them) and on the lower half of the body (or only on the shoulder). This black spotting is not based on poor fire control during firing, as it has been confirmed that the carbon was absorbed after the pottery was fired, and there is no better interpretation than that it was caused when the pottery was removed from the hot vessel after firing was completed by inserting a piece of pottery plate between them.

Decoration: Yayoi earthenware is often decorated with sunken patterns, often in the form of spatula-patterns, sunken line patterns (e.g., early period), and comb-patterns (mid period). In addition, there are bamboo tube patterns and shell patterns (also in the Early Period). In eastern Japan, the use of jomon continues, with some fine jomon (Middle and Late Period). There are special ones: primitive paintings depicting deer, birds, boats, warehouses, etc. (late middle Kinai) symbolic style patterns (late Kinai). Large clay patterns are rare, including those from eastern Japan, and are often only small in size. In addition, in the Kinai region and other areas, Tan-nuri patterns of foliage, thunder, running water, and other patterns were developed at the end of the Early Period.

Yayoi earthenware with a special form is called gourd-shaped earthenware, which is made by stacking two jars on top of each other (Early and Late Period). However, since the excavated examples of fukube in ancient Japan are all simple in form and do not exhibit the so-called hyasago-shape, it is too early to assume that they were immediately copied from hyasago-shaped vessels. In addition, there is a type of earthenware (Late Ise Bay period) that resembles the shape of a fish, but these are all special examples. Other examples of vessels copied from other materials include a wooden cup (Middle Kinai period) and a cup (Late Middle Kyushu period).