Chojiro

The Momoyama period was a time of great change in the history of Japanese pottery. Examples of this include the birth of kiln arts such as Shino and Oribe in the Seto region, which were completely different from the traditional traditions of the time, and the emergence of Karatsu pottery in Kyushu. Raku ware is another type of pottery that emerged in the same period, and it is worth noting that it had a significant impact on the development of pottery in Japan in later years.

It was previously thought that Raku ware was started by Chojiro, and then handed down and developed by Jokei and Doiri. However, as a result of research carried out on the basis of ancient documents handed down in the Raku family and newly discovered ceramics, etc., which were made public in recent years, it has become known that there are various errors in the conventional wisdom to date.

The old documents of the Raku family, the head family of Raku ware, are the handwritten notes of the fourth generation, So-nyu, and are accompanied by a postscript dated December 17th, 1788. According to this, a person called So-kei is given a prominent place alongside Chojiro.

Kaku

- Ameya Onna Hiku ni ya

- Chojiro, born in the year of the fire snake, 200 years after the year of the snake

- Chojiro, the first to try it

- Shozaburo, also known as Sōmi, born in the year of the dragon, 270 years after the year of the snake

However, this Sōmi is the grandson of the Sōmi who lived in the temple

Also, there is a record of a visit from a certain person

There is a record of a visit from a certain person

One, I am called Kichizaemon.

Kichizaemon

I am also called Yotsugi. My name is Jōka

and my name is Shōzaemon.

The date is the 29th day of the month.

One, my name is Kichibei.

One, my name is Kichizaemon.

This seal is the only one that remains.

Kichizaemon, first year of Genroku

Written on the 17th day of the 12th month of the 5th year of the Bunsei era

Raku family tree

- The founder Ameya

- Ameya (the nun) Ameya’s son

- The nun Ameya’s wife Chojiro, born in the year of the Dragon, lived for 100 years

From this point on, Chojiro was known as

His common name was Yoshizaemon, and his Buddhist name was Shozan.

He was born in the year of the Dragon, in the 70th year of the era of the Emperor Mutsuhito.

However, he was born in the year of the Dragon, in the 70th year of the era of the Emperor Mutsuhito.

He received this seal from the great warlord, Oda Nobunaga.

He received this seal from the great warlord, Oda Nobunaga.

Shokei

Gokichizaemon. However, he received this seal from the great warlord, Oda Nobunaga.

I have received this seal from

Yoshizane

My Buddhist name is Joka

I am the brother of Maenoshozaemon Both of us have this seal

(This is the elder brother of Yoshizane)

father-in-law

Kichizaemon is called Kichibei. His Buddhist name is Doi

At this time, there is an inscription on the flower vase that says “Sotan no nanka

Therefore, this

Kichizaemon is called nanka

Kichizaemon, and before this, he was called Sahei, and after this, he was called

Kichizaemon. There are two more seals, and the seal on the right is called ”Doraiku”

The above is a summary of two of the three “Souiri Documents” that exist, and the fact that the family tree’s Soukei is actually Soukei can be seen from the fact that the character for “kei” is written in place of the character for “kei”.

This Soukei is said to be the same person as the Soukei in the inscription above the portrait of Rikyu, which is said to have been painted by Hasegawa Tohaku and is handed down in the Omote Senke. The author of the inscription is Shun’oku Sōen, the 111th abbot of the Daitoku-ji temple, who is said to have written it on the fourth day of the fourth month of the fourth year of the Bunroku era (1596) at the request of “Rikyū’s trusted retainer, Sōkei”.

Another example of the name Sokei being seen is on a Raku ware incense burner in the shape of a lion facing forward, colored with yellow and green glazes, on which the following is engraved on the belly: “Toshi roku tenka ichi Tanaka Sokei (signature) Bunroku 2nd year, September, lucky day”. As the year and month on this inscription are the same as those on the aforementioned image of Rikyu, and as the family name is also the same as Rikyu’s, it is thought that there is a deep connection between this incense burner and the image, and it is also said that it may have been made for use in Rikyu’s memorial service.

From these materials, it is recognized that the lineage of Raku ware from the Chojiro period is as follows.

Chojiro─────────Chojiro

│ Chojiro’s wife

Sokei – Shozaburo Sōmai – Daughter

└ Kichizaemon Chōkei – Kichibei Doi

└ Doraku

As you can see, Chojiro’s direct line died out in the next generation, but the Sōkei line continued, so we know that Raku ware developed through the descendants of Sōkei, and that the tea bowls now known as Chojiro , it is easy to imagine that the works of the first and second Chojiro, as well as those of Sokei, Sōmai and Jōkei, are included in this lineage, and therefore it can be said that Chōjirō ware is a generic term for these works.

Now, there is a lion figure in Raku ware that is recognized as an example of the work of the first Chojiro, with a dull yellow glaze applied lightly. It is said that this lion, which appears to be standing on its head, was a model of a decorative tile that adorns the gable of a roof, and the magnificent style of the piece and the extraordinary modeling skills used can be seen. The phrase “Tensho 2 spring, by order of Chojiro” on the belly clearly indicates the period of its production, and the existence of such a model of a ridge-end tile suggests that Chojiro was originally a craftsman involved in tile-making. It is said that Chojiro was the son of a naturalized Japanese “ameya” (potter), but his homeland is said to have been either China or Korea, and there is no consensus on this. In the biography of Hon’ami Koetsu, who is thought to have had a close relationship with the Raku family, he is described as being Chinese, and the fact that the glaze on these lion-shaped roof tiles is a so-called lead glaze and is yellow, supports Koetsu’s theory that Chojiro’s homeland was China.

In Korea, lead-based colored glazes were used from the Silla period to the early Goryeo period, but not during the Yi Dynasty, which corresponds to the Momoyama period. Furthermore, the glaze colors were limited to a single copper-based green. In China, lead glazes were used from the Han period, and this tradition continued uninterrupted until the Qing dynasty of the early modern era. The lead-glazed pottery of the Qing dynasty is known as Koji ware, and unlike Korean pottery, yellow, purple and other colors are used alongside green. As is well known, the majority of Raku ware is black or red, but the red Raku glaze is the same as the yellow of Koji ware, and so it is thought that the origins of Raku ware lie in China, and the fact that the most rudimentary examples of glaze can be seen in the aforementioned model of the lid-stopper tile suggests that Chojiro was of Chinese descent.

Now, the year Tensho 2 engraved on this tile is two years before Oda Nobunaga completed the construction of Azuchi Castle. The “Chronicles of Lord Nobunaga” states that the production of roof tiles for this construction was overseen by a Chinese named Ikkan. The fact that Chojiro’s nationality was the same as Ikkan’s, and that he was a tile maker, may have led to his association with Ikkan and the production of these roof tiles.

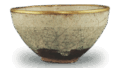

The surviving examples of early Raku ware, represented by Chojiro, include the lion-shaped lid tiles and incense burners mentioned above, as well as containers for burning incense and dishes, but the majority of these are tea bowls.

They were called “imayaki chawan”, “kuroyaki chawan”, “kuro chawan”, or “yaki chawan”, but not all of these were raku chawan. If we look at the tea ceremony records of Hisamasa Matsuya, we can see that on September 14th 1588 there were “imayaki chawan”, on the 18th “imayaki kuro chawan”, on October 16th “yakichawan”, and on November 14th “kuroyaki chawan”. The term “shimasushi kuro chawan” also appears in the “Nanbokuroku” (a collection of writings by the tea master Takeno Jouou). The fact that the tea bowls used at tea ceremonies held on days that were only a few days apart are referred to by such different names suggests that they may not have been the same. However, it is unlikely that there is a significant mistake in assuming that most of the tea bowls, other than the “yaki-chawan”, were raku ware.

The name “Ima-yaki tea bowls” appears in the “Matsuya-kai Ki” around the end of the 15th year of the Tensho era, and is mentioned frequently until the middle of the 16th year of the Tensho era, while the “Ima-yaki black tea bowls” are first mentioned in the same year in September. As is well known, Raku tea bowls come in red and black, but the records do not indicate whether the Ima-yaki tea bowls that first appeared in the “Matsuya-kai Ki” were red or black. However, in the Tsuda Sōkyū Diary, the name “red tea bowl” is recorded more than ten times between the first appearance on February 1st, 1581 and 1583, and in the diary of Imai Sōkyū, “tea bowl tree guardian” is recorded in 1583. Considering that the glaze on the aforementioned lid tiles, which are the earliest examples of Raku ware, is reddish, it is thought that the red tea bowls that appeared from 1581 were Ima-yaki Raku tea bowls. Therefore, it can be said that red Raku tea bowls were created before black ones.

These red tea bowls were first used at gatherings that Sōkyū held with his close friends, such as Rikyū, Sōji Yamagami and Sōan Bandaiya. On November 25th, 1582, at a gathering held by Sōkyū at Daitoku-ji temple, he invited Shun’oku Sōen, who used a haikatsutenmoku bowl, but the other guests were served tea from red tea bowls and scattered tea bowls. Judging from this example, it can be said that red tea bowls were rarely used at formal tea gatherings. In the “Sotan Diary”, Kamiya Sotan, who was invited to a tea gathering held by Rikyu at the Jyurakudai residence on September 10th, 1590, wrote that Rikyu said, “The black tea bowls are so plain that the lord dislikes them…” Hideyoshi was a fan of showy things, so Koetsu says that the tea ceremonies of the time were also very showy. Therefore, the showy red tea bowls that had already started to appear in 1581 must have been seen at many tea ceremonies after that. However, the reason why examples of them are extremely rare is probably because the red tea bowls were not made to a standard suitable for use in tea ceremonies.

However, there are also examples of excellent tea bowls, such as the “Hayabune” bowl, which is said to have been coveted by Gamo Ujisato and Hosokawa Tadaoki. In a letter from Rikyu to Hidehisa, the Grand Minister of Yamato, we see an example of Rikyu inquiring, “I have just made two tea bowls. Would you like one of them to be red? Seta Sōbu, one of the seven disciples of Rikyū, in a letter to him, “…the red tea bowls that are being made privately by Chōji are especially wonderful…”, we can assume that there was considerable interest in red tea bowls among the famous tea masters of the time. The fact that black tea bowls appear frequently in the records may be due to the fact that the tea ceremony, which aims for wabi, favored black, but it may also be the result of the fact that, due to the immaturity of the firing of red tea bowls, it was not possible to obtain good tea bowls.

Sōji Yamagami, a tea master from the Tenshō period, wrote about his preferences for tea bowls around 1588, saying, “In general, tea bowls from the Tang dynasty are popular, but today, Korean tea bowls and Seto tea bowls are also popular, and Imayaki tea bowls are also popular…”. The types of Korean tea bowls referred to at the time included the Ido tea bowl, as well as the “hirataki koryo tea bowl”, “shiroki koryo tea bowl”, “kuroki koryo tea bowl” and “koryo tea bowl”. Although the details of the “shiroki”, “kuroki” and “koryo” koryo tea bowls are not known, the Ido tea bowl is well-known and many examples have survived to the present day. It is also possible to make a rough guess at the shape of the “flat-rimmed Koryo tea bowls”. It is very easy to imagine that the shapes and glaze colors of the Koryo tea bowls that were popular at the time were copied in the Imayaki tea bowls, and it is thought that the red tea bowls with the “Koutou” and “Dojoji” inscriptions are equivalent to these.

In addition, the “Matsuya-kai Ki” (a record of the Matsuya tea ceremony society) states that the tea bowl used in the morning tea ceremony held on October 13th, 1586, by Chubo Gengo and Nara’s deputy Inoue Takashi, was a “tea bowl in the style of Soeki”.

As mentioned above, the Raku tea bowls known as Chojiro were made by several people, and one of them, Sokei, had a special relationship with Rikyu, who would have ordered the Chojiro family to make tea bowls in the shapes he liked, or to make tea bowls that had been ordered by other people. The details of Sokei’s preferences are not known, but one example that hints at them is

“The three of us are here this morning. I am thinking about this and that, but I have not heard anything. I would like to ask you to introduce us to Daikoku. We are going to Matsukashima-dono’s house by boat. I am very sorry to trouble you, but I would like to discuss this matter with you. I will be able to finish today. I will come to see you tomorrow. Whatever it is, I will do my best to get the fast boat ready for you. I humbly ask that you send the fast-moving boat to the Lord of Echizen, and that you send the large black tea bowl to Lord Oda. I apologize for any inconvenience this may cause.

I will send two or three people.

This is a letter from Rikyu that was attached to the fast-moving boat.

From the meaning of the letter on the right, it can be inferred that the tea bowl with the name “Hayafune” and the name “Daikoku” was the tea bowl that Rikyu loved the most, so it is thought that it was a shape and glaze color that Rikyu liked. Therefore, it can be said that the styles of “Toyobo”, “Ayame”, “Muichimono”, and “Kimamori”, which show a style similar to Hayafune, were one of Rikyu’s favorite styles. In addition, the tea bowls “Kitano”, “Kuro-chawan”, “Tarobo” and “Jirobo”, which are similar in style to the “Daikoku” tea bowl, can also be said to be the so-called Sōeki-gata tea bowls that were favored by Rikyu.

In addition to this, there is another example of a tea bowl that was favored by Rikyu, which was named “Mukiguri”. It is said that this square-shaped tea bowl was modeled on the shape of the four-sided tea kettle made by Kojomi, which is said to have been a favorite of Rikyu, but it is the only example of this shape that we know of, and it is the only shape that Rikyu is known to have favored.

Michi-iri

The early Raku tea bowls, which are represented by the works of Chojiro, are simple in shape and have a rustic beauty. However, when it comes to Raku tea bowls from the early Edo period, the wabi-like beauty of this introverted beauty fades, and the tea bowls become more showy and outwardly beautiful. Therefore, the works of Doiri, which represent the Raku tea bowls of this period, can be said to be in stark contrast to the style of the tea bowls of the Chojiro kiln.

Michiiri was the son of Kichizaemon Tsunekiyo, who is said to have been the most skilled of all the Raku family, and he is said to have died on February 23, 1656 at the age of 58. There is also a different theory that he was 83 years old, but considering his grandfather’s age, this theory is not very plausible. According to the genealogy of the Raku family, Doi is listed as the third generation, but if you trace the lineage from the beginning of Raku ware, from Chojiro to the second Chojiro, Sōmai, and Sōkei, it makes five generations. The reason why the ‘Banpo Zensho’ lists Doi as the fifth generation is probably because of this history of Raku ware.

It seems that the main type of pottery being fired in Kyoto during the period when Doi was active, from the end of the Genna era to the Shoho era, was soft-paste pottery, and the kiln sites mentioned in this period include Yasaka, Awataguchi and Oshikoji.

In the section of the diary of Hourin, the abbot of Rokuonji Temple, who died on August 28th, 1668 at the age of 76, it is recorded that Funakoshi Gaki, a retainer of Hojo Kyudayu, the deputy of Kawachi Province, was leaving Kyoto , and it is stated that this incense container was made by the potter Seibei of Yasaka, and that it was made in two colors, blue and purple. Also, at that time, Horin visited Seibei’s workshop in Yasaka, guided by Ohira Gohei, a tool dealer who often visited Seibei’s place, and observed the making of tea containers, incense burners and incense containers on the pottery wheel. He was given a blue-glazed bowl by Seibei as a gift. From this example, we know that Kyoto pottery was also being fired in Yasaka at the time, and we can imagine that the glaze on the wisteria-shaped incense container made at Seibei’s pottery was similar to that of Koji pottery, so it is possible that the blue-glazed bowl that was presented to Hou It is possible to assume that the blue-glazed bowl presented to Horin was also fired in Seibei’s kiln and was not a hard-paste ware, but the fact that it is specifically noted as “Imayaki” is worth noting. Also, the ume-e bowl that Gohei Gohei, mentioned above, who visited Horin to offer his New Year’s greetings in the fifth year of the Shoho era, presented along with the Yasakani ware trivet-shaped lid rest is also “Ima-yaki”, and is distinguished from the lid rest. From examples like this, it is thought that the blue-glazed bowl and the bowl with a plum design that were given to Horin were not made at the Seibei kiln, but were probably Raku ware, which was called “Imayaki” at the time.

Furthermore, in the tea ceremony records of Hisashige Matsuya from 1637, it is thought that there was a “red tea bowl of Shuraku ware”, so it seems that some people referred to Raku ware as Juraku ware. However, in general, Raku ware was more commonly known by the name “Imayaki”.

Just as it is said that Rikyu’s guidance was significant for Chojiro ware, it is said that Doi also received guidance from Sen Sōtan. However, Doi’s works do not use the so-called Sōyōkei style of form. It is well known that Doi’s nickname was “Nōkō”.

The origin of this nickname is said to be that when Sen Sōtan visited the Noko tea house in the area between the villages of Nojiri in Kannabe-mura, Suzuka-gun, Ise, and the present-day Nokiji in Fuke-cho, Kameyama City, he made a double-layered bamboo flower vase and gave it to Do’iri, naming it “Noko” after the place. Later, when Sōtan visited Doiri, he said, “I’m going to see Nonkō,” and this became Doiri’s nickname, according to Eisaku Oda. This story suggests that Doiri was a favorite of Sōtan. In addition, the red tea bowl made by Doiri, named “Horin” – said to have been a treasured item of the Sen family, and later passed down to the Matsudaira family of the Izumo Matsue domain – was given to the priest Horin of Rokuonji Temple, who was one of the leading figures of the tea ceremony in the court noble society of the time, with the recommendation of Sotatsu. This also serves to underline the relationship between Sotatsu and Doiri. This relationship between Hōrin and Sōtan was extremely close, as seen in the example of Sōtan borrowing money from Hōrin, but the fact that Sōtan was borrowing money suggests that his finances were not particularly good. Therefore, it is likely that Sotatsu’s support for Doitsu was not very significant financially. Koetsu’s comment that “masters are always poor” shows one aspect of the situation at the time.

Doitsu was also given a lot of guidance by Koetsu. The nickname “Nokou” originally meant a young tree sprout, and it is a corrupted word from an old word used in the old days in the inland regions of Japan, so it is likely that Koetsu, who loved Doitsu, started using it because of the close relationship between Koetsu and Doitsu.

As can be seen from the fact that Koetsu says, “We were able to obtain the secret of making medicine from Kichibei, and we are now able to make it with peace of mind…”, there are many similarities between the tea bowls of Doi and Koetsu. In particular, the most striking thing is the extremely glossy glaze. The reason for this is said to be that, around that time, the structure of the Raku family kilns changed and extremely high heat was used. It is also said that this is the reason why there are so many cracks in Koetsu’s tea bowls. However, there are no cracks in Doi’s tea bowls. This is thought to show the difference between the pottery of professionals and amateurs, born of the difference in the fineness of the kneading of the clay. On the other hand, it is thought that Doi, who was a professional potter, would not have been allowed to release such tea bowls, which could be seen as being defective, to the public. The reason why there are no tea bowls with kiln cracks in Doi’s legacy is probably because of this.

Like the tea bowls of Chojiro and Koetsu, seven of Doi’s tea bowls are also considered to be masterpieces, and are known as the “Seven Non-Ko”. These include a black tea bowl with the name “Masu”, a black tea bowl with the name “Chidori”, a black tea bowl with the name “Inazuma”, a black tea bowl with the name “Shishi”, and a red tea bowl with the name “Horin”, a red tea bowl with the name “Wakayama”, and a red tea bowl with the name “Tsuru”. Some of them, such as the tea bowl with the “Masu” mark, have a unique shape with a gently rounded body that was not seen in previous Raku tea bowls, but in general they are relatively gentle in appearance, and there are no examples of the extreme eccentricity seen in later Raku tea bowls. Compared to the shape of Koetsu’s tea bowls, they seem to lack the freedom and exuberance of his work. This was probably because, like the cracks in the kiln, they were made by a professional potter. However, the thin body and the tension that fills the curved surface of the body, as well as the spacious interior, show the extraordinary modeling ability of Doi.

In terms of form, Doi’s tea bowls do not show the same kind of variation as Koetsu’s tea bowls, but in terms of glaze, they are far more diverse than Koetsu’s. One example is the use of so-called curtain glaze, where the glaze flows from the rim to the body of the bowl. This glaze is a technique that was not seen in Raku tea bowls before Doi, and can be said to be a new invention by Doi. In addition, the red glaze with various colors dotted in the glossy black glaze also originated from Doi tea bowls, and the black glaze surface that emits a light similar to that of a jewel beetle’s wings also originated from Doi tea bowls, so these red glazes and jewel beetle-like luster can also be said to be Doi’s new discoveries. Furthermore, it is said that this luster, which resembles the wings of a jewel beetle, appears because the glaze layer is thick, just like the makie glaze. What is also worth noting about the Doiri tea bowls is the use of white glaze, as seen in the tea bowl with the “Shishi” (lion) mark, which is one of the seven non-glazed types. White glaze is applied in a so-called katamigawari style, as in the tea bowl with the “Shishi” (lion) mark, or in an abstract pattern, as in the tea bowl with the “Zansetsu” (lingering snow) mark, or in a brushstroke pattern.

The aforementioned “Ima-yaki” tea bowl is said to have a plum blossom design, which is probably expressed in white painting. A kiln-shaped container for burning incense used in the art of kodo (incense ceremony) was discovered at the burial site of the second Tokugawa shogun, Hidetada. The fact that the glaze on this container was white and that it bore the Tokkei seal indicates that the use of white glaze in Raku ware dates back to the time of Tokkei. However, it was only used to cover the surface of the vessel in white, and was not used for decorative patterns as seen in the Doiri tea bowls. Therefore, it can also be said that this was another new idea from Doiri. This may also be seen as a reflection of the fact that at the time, interest in pottery was leaning towards so-called painted ware. In addition, some of the Doiri tea bowls are innovative in that the glaze on the surface is rough and coarse, like the clay itself, and has been covered with a so-called “sand glaze”.

The signature is a dignified example of the so-called Jiraku seal, in which the “white” between the “threads” of the “raku” character has been changed to a “self” character, and is stamped on the back of the foot of the tea bowl. However, there are also exceptions, such as the black tea bowl with the “Sanko” mark, where the mark is pressed into the area between the body and the waist, making the mark a kind of decoration. This style of mark, where the “white” becomes “ji”, is also used in the works of Sokei, Jokei and the 9th generation Ryojin, but the mark of Doi shows a difference, with the left “ito” becoming “nomu”. It was said in the old days that the nickname “Nonko” for Doi was derived from this “nomu”.

Koetsu

Raku ware, which was created by Chojiro at the beginning of the Momoyama period, was taken over by the descendants of Sokei Tanaka, the wife of the second Chojiro, and became specialized in the firing of tea utensils. On the other hand, as tea became more popular, people related to the Raku family, such as Tamamizu Yahei, and also people who were not related to the Raku family, tried their hand at making Raku ware as a profession or as a hobby. As a result, the kilns of the Raku family came to be called “main kilns”, and those of other potters came to be called “side kilns” to distinguish between them. Among the many side kilns, the Raku tea bowls made by Hon’ami Koetsu, who made his living polishing swords, were highly acclaimed and well known from an early stage.

Koetsu was a master calligrapher, and was known as one of the three great calligraphers of the Kan’ei era, along with Gosui’no-in and Shokado Shōjō. There is a story that when someone asked Koetsu which of the three Kansai calligraphers was the best, he raised his finger and said, “First of all…”, showing his confidence in his own calligraphy. However, when we see that he also said, “When it comes to making pottery, I am surpassed by Seisei-o (Shokado)…” it seems that he was also very proud of his Raku ware.

Koetsu is quoted as saying, “I make pottery from the good clay of Takagamine as and when I can…”, so we can imagine that he mainly used the clay from Takagamine in the northern part of Kyoto, where he lived in seclusion, to make his pottery. However, there is also a letter addressed to Kichizaemon that says “Please bring four-tenths of a bowl of white clay and red clay as soon as possible…”, so it is thought that he also used clay from other places besides Takagamine. Furthermore, from the letters in which he asks Yoshizaemon if the tea bowls are ready and requests that he apply the glaze, it can be inferred that the body of the tea bowls was made at his residence in Takagamine, which was a craft village, and that the glazing and firing were entrusted entirely to Yoshizaemon, the Raku ware kiln master. In addition, when we see that Koetsu is extolling the virtues of Raku ware, saying “the current Kichibei is a master of Raku ware…”, we can assume that the Yoshizaemon mentioned in these letters was Jokei.

Therefore, it can be seen that Koetsu and Jokei were extremely close, as if they could say “I’m coming to visit you”. Jokei died in 1635, and Koetsu died in 1637, so their relationship must have started early. As we know that Koetsu was given the Takagamine estate by Ieyasu in 1615, he was very close to the Tokugawa family. The discovery of a container for burning incense made by Jokei at the burial site of the second shogun Hidetada is not surprising when we consider the relationship between the Tokugawa family and Jokei, with Koetsu at the center.

As you can see, Koetsu’s tea bowls, which were made with the help of the Raku family’s Yoshizaemon Tsunekei and Kichibei Michinori, were the focus of much attention from the public even at the time, and it seems that they were often commissioned by powerful and influential people who were interested in the tea ceremony. A letter to Kato Shikibu no Sukesuke Akinari, the lord of Iyo Matsuyama Castle, says “…the tea bowl that you requested, Lord Samukawa, is almost complete, and I have sent it to you the other day…” This letter shows the correspondence between them at the time. However, Koetsu had a high level of self-discipline and said that he had no interest in making a name for himself in the pottery world, and that he did not want to make pottery his family business. It is thought that the number of tea bowls he made was small, and therefore the number of tea bowls that have survived to the present day is extremely rare.

The tea bowls that are now known as Koetsu’s work and have survived include the black and white tea bowl with the inscription “Fujiyama” that is accompanied by a box with Koetsu’s autograph and seal, as well as the black tea bowls with the inscriptions “Amagumo”, “Shigure”, and “Kugai”, and the red tea bowls with the inscriptions “Kaga”, “Bishamon-do”, “Shoji”, and “Seppou”. Also, the white-glazed “Ariake” tea bowl is also famous for its unique glaze.

Now, the beauty that can be found in these Koetsu tea bowls is beyond words.

However, if we were to single out some of the characteristics, they would be the vastness of the spirit, the high level of refinement, the sense of grandeur that makes the tea bowls seem larger than they actually are, and the simple yet complex color tones. These characteristics can already be seen in the Chojiro ware tea bowls, so it could be said that they were of the same period. However, compared to Chojiro ware, this is particularly noticeable in Koetsu’s life, which was extremely frugal, as can be seen from the fact that, despite being from the wealthy Hon’ami family, “Koetsu had many strange things happen to him, but the only thing he learned was that from the time he was 20 until he died at the age of 80, he lived with only one servant and one cook”. In a letter of advice to Matsudaira Nobutsuna, he also expressed his desire for tolerance, saying, “The government of the world is like washing a multi-tiered box with a scrubbing brush”. It is this personality of Koetsu that is expressed in the tea bowls.

Looking at the Koetsu tea bowls from the perspective of the way they were made, they can be broadly divided into three types. This is similar to the differences between the three main styles of calligraphy: “sho” (formal), “gyo” (running) and “so” (cursive). The “Fuji” and “Kaga” types are in the “sho” category, while the “Shigure”, “Bishamon-do” and “Amagumo” types are in the “gyo” category, and the “Seppou” and “Otome” types are in the “so” category.

The tea bowls in this “true” category have a straight-sided shape, like a rock with a steep side, and the border between the body and the waist is angular and clearly defined, while the surface from the waist to the foot is flat. The footring is extremely low, small, and distorted, so it is close to an irregular polygon, and its appearance is reminiscent of a thinly sliced tube-shaped fish cake. This type of foot is rarely seen in Chojiro ware tea bowls, but a glimpse of it can be seen in the red tea bowl “Kotatsu” and the black tea bowl “Toyobo”, so it is thought that Koetsu tea bowls were influenced by Chojiro ware. Konoike Michioku, a tea master and connoisseur who lived from the Genroku to the Kyoho periods, said that many of the tea bowls known as Chojiro ware were actually made by Koetsu and Kosa. This is probably because of the style of the foot ring.

The “Fuji”, “Kaga” and “Shichiri” wares, which fall into the “true” category, are characterized by the large number of marks left by the brush, and this is particularly noticeable on the sides. This style of making is not seen at all in the Chojiro ware, so it can be said that it is unique to Koetsu tea bowls.

The Koetsu tea bowls listed under the “line” category also have upright sides, just like the Fujiyama and other bowls. However, the chamfered lines are rarely seen. In addition, the surface that transitions from the body to the waist is gently curved, so it is difficult to clearly distinguish the boundary between the body and waist. The shape of the body and waist is very similar to that of the Daikoku ware of the Chojiro kiln, so it is safe to say that it is a style that has been influenced by the Daikoku style. The foot of this type of tea bowl is also low and small, and the fact that there is no convex bulge in the center is the same as the foot of a “true” tea bowl. Furthermore, there are also examples such as the “Amagumo” tea bowl, where there is no border between the foot and the underside of the foot, and the style is similar to that of a go-sutsu (a type of container used to hold go stones).

The style of the next type, “Kusa”, is seen in red tea bowls such as “Yukiho”, “Otome”, and “Kamiya”. These are the most elegant of Koetsu tea bowls, and show a style that is full of wildness. If the “true” type is like a figure with a collar and a dignified appearance, then this can be said to be a figure that is relaxed in a yukata. Therefore, it can be said that there is a deep sense of familiarity in the appearance of this type of tea bowl.

The foot of the Otsu Gozen bowl is lower than the waist, so at first glance it looks as if there is no foot, and it has a so-called “pushed-up” base. It is also said that the tactile sensation of Raku tea bowls, which is said to be one of the features that make them suitable for drinking tea, is best in this type of Koetsu tea bowl.

This type of eccentric shape is often seen in Oribe ware. In a letter from Koetsu to Kato Shikibu Shosuke, the name Furuta Oribe appears, as in “I saw your letter yesterday… I think you have already had tea with Oribe-dono, but not with Furuta Oribe…” Also, Haya-ya Shōeki, who was close friends with Koetsu, wrote, “There is a man called Jitokusai in Hon’ami, who has been interested in this art since he was young was fond of this art from a young age, and he was always eager to learn more, so he visited both houses (Furuta Oribe and Oda Uraku) frequently, and he was always making progress. Therefore, it is thought that these warped-shaped tea bowls were created under the influence of Oribe. When we consider that the Gosomaru tea bowl, which was called “Furuta Koryo”, was owned by Oribe, we can understand that the chamfered style of the “Fuji” tea bowl shown above was not created by chance.

The glaze of these Koetsu tea bowls is characterized by its vivid color and luster. As mentioned above, Koetsu asked Kichizaemon to fire his tea bowls, so the fact that many of the Koetsu tea bowls have this type of glaze suggests that there was a major change in the firing method of the Raku ware of the Raku family around this time. The fact that the unglazed clay of tea bowls such as “Amagumo”, “Shoji” and “Yukiho” show many cracks indicates that they were fired at a high temperature, and the luster of the glaze was also probably the result of the high heat.

As we have seen, Koetsu tea bowls show many characteristics that are not seen in Chojiro ware, but if we were to sum up their appeal, it would be that they are highly individualistic. As we have mentioned, Chojiro ware was created by Chojiro and several members of the Sokei school, and was produced in a small-scale family business. As a result, the Raku ware produced by these potters lacked individuality and was rather unremarkable. However, when Raku ware was made by someone with artistic talent like Koetsu, it was natural that the distinctive characteristics of Raku ware would be brought out to the full, and this is probably why Koetsu’s tea bowls are so highly regarded.

Furthermore, Koetsu tea bowls are often around 375 grams in weight, with Fujiyama and Otome weighing around 370 grams, Amagumo weighing 350 grams, and Shigure weighing 378 grams. This weight seems to be just right for holding in the palm of the hand when drinking tea. Therefore, it can be said that Koetsu took this into consideration when making his tea bowls.

Karatsu, Takatori, Satsuma

It is well known that the pottery industry in various parts of Kyushu was created by potters from the Korean Peninsula who accompanied the various generals who had fought in Hideyoshi Toyotomi’s invasions of Korea in the Bunroku and Keicho periods when they returned to Japan. These include Satsuma ware, Ueno ware, Takatori ware, Higo ware, etc., but the pottery of the Hizen Karatsu region was particularly famous, to the extent that the name for pottery was called “Karatsu”.

The name “Karatsu” pottery first appears in records in October 1603, when the Nara lacquer artist Hisashige Matsuya was invited to a tea ceremony hosted by Sen no Rikyu in Kyoto, and it is recorded that “Karatsu water jars” were used at the event. The same year, in August, “Karatsu tea bowls” were used at Sen Sōtan’s tea ceremony in February of the same year, and ‘Karatsu water jars with matching lids’ and ‘Shuraku-yaki tea bowls’ were used at a tea ceremony at Shōmyō-ji temple in Nara in March of the same year. From this example, it is estimated that the name of Karatsu ware finally became known to the world in the middle of the Keicho period. On the other hand, the tea ceremony memorandum by Hisashige mentions that “Higo ware tea bowls” were used at the tea ceremony held by Okuhira Kinya in December 1626, “Chikuzen ware tea caddies” were used at the tea ceremony held by Nakamura Sakyo in January 1629, and “Tsuru no aru Ogura ware water jars” were used at the tea ceremony held by Miyake Bōyō in Kyoto in March 1630. It is also known that a “Satsuma-yaki tea caddy with a shoulder” was used at a tea ceremony held by the Kyoto kara-mono-ya Do-mai in May of the 14th year of the Kan’ei era. This Higo ware is probably Yatsushiro ware, and it is said that in 1632, Hosokawa Tadaoki invited Ueno Kizo, who had been involved in the production of Ueno ware in Bungo Province, to open a kiln in the village of Takada in Yatsushiro County, Higo Province, so it is thought that the Higo ware mentioned in the Hisashige Kai Ki was the predecessor of Yatsushiro ware. Chikuzen ware refers to Takatori ware, which was started by Kuroda Nagamasa, who ordered the potter Hachiyama (later Hachizo) to open a kiln at the foot of Mt. Takatori around 1600, when he was transferred from Buzen to Chikuzen. The Takatori ware has since moved from place to place, being fired in places such as Iso (Nogata City), Yamada (Yamada City Kamiyamada), Shirahata (Iizuka City Kofukuromachi), Koishiwara (Asakura County), etc., but around the Kan’ei era it was being fired in the Shirahata kiln, and so the tea caddies in the Hisashige Kai Ki were probably also made in the same kiln. It is well known that Takatori ware was one of the so-called Enshu Seven Kilns chosen by Kobori Enshu, but it is said that the tea caddies born at Shirahata were extremely elaborate works, with the inside glazed as well, and so it is imagined that the tea caddies noted by Hisashige were of the same type. In addition, it is thought that Kokura ware was produced in Ueno, Buzen Province, but the fact that the names of these Higo, Chikuzen and Kokura wares, which are all in the same lineage as Karatsu ware, appeared more than 20 years after Karatsu ware, shows that Karatsu ware represents Korean-style pottery.

Karatsu ware was originally mainly used for firing containers for everyday life. Therefore, the water jars and tea bowls mentioned in the above-mentioned “Matsuya-kai Ki” were probably the so-called “mitate-mono” (things selected for their beauty) that the tea ceremony enthusiasts of the time chose from among these miscellaneous vessels as tea utensils, and the old Karatsu tea bowls with no artificial touches, such as those called “Okukoma”, “Zenbiri” and “Nenuke”, would correspond to this category.

The shape of the upper and lower rims of these bowls, which are often found in the so-called Kuro-Karatsu tea bowls with bluish black glazes, is wider at the top and narrower at the bottom, and this suggests that they were not simply made as everyday use bowls, but that they were made with the intention of being used for tea ceremonies.

In April 1704, Matsuya Hisashige was invited to a tea ceremony held by Hosokawa Sansai in Yoshida, Kyoto, and in his report he mentions that a Higo ware tea bowl and an Ogura ware water jar were used, and he also illustrates the water jar, which was shaped like the Chinese character “工” (meaning “craftsman”). This shape is said to have been popular in the early Edo period, and is often seen in Iga ware and Bizen ware water jars. The fact that this shape is also seen in the Kogura ware, which is related to the Karatsu ware, suggests that by the Kan’ei era (1624-1644), the Karatsu ware, which had previously been mainly used for making miscellaneous vessels, was also being used to make tea ceremony utensils. The shape of the aforementioned black Karatsu tea bowl is also a reflection of this.

Also, the small bowl with a half-open bellflower shape, called “Wariyama-giri”, is illustrated in the tea ceremony by Hosokawa Sansai mentioned above, and it is noteworthy that it is accompanied by a small bowl from the Kokura ware. This Wariyama-giri-style side dish was highly prized by tea masters from early on, who praised it as Karatsu ware. However, when we look at the fact that similar pieces have been found at the Ueno kiln site in Buzen, which was a sister kiln, and that it is listed as Kokura ware in the Kujyu-kai Ki, we can see that the descriptions of the kiln sites of the time were relatively accurate, which is interesting.

It is said that the appearance of tea ceremony-style pottery in Karatsu ware was greatly influenced by the guidance of Furuta Oribe Shigenari (1592-1642), who died in 1615 at the age of 70. In a letter he wrote to his wife, Lady Kitamasa, while he was staying at Hizen Nagoya, Hideyoshi wrote

“I am doing well. It is not as cold as it was in the middle of winter, and I am doing well. I am spending my days and nights in the tea room. Please write back.

, it can be seen that Hideyoshi often held tea ceremonies to pass the time. It is thought that Oribe, who had been staying at Nagoya for about a year and a half from March 1592, may have served as Hideyoshi’s tea ceremony partner, and it is said that the reason that Karatsu ware has the shape that Oribe liked is because of his guidance. However, in the notes of Hisayoshi Matsuya, who attended several tea ceremonies held by Oribe between 1596 and 1607, it is recorded that Seto tea bowls and water jars, Imadaka Rai tea bowls, Shigaraki ware water jars, and Bizen ware water jars were used, and the name Karatsu is not mentioned. As is well known, after the death of Rikyu, Oribe was the leader of the tea ceremony world, as is written in the “Sunpu Ki” (“Records of Sunpu”) as “At that time, he was the master of the tea ceremony, and he was highly respected by the shogunate. Therefore, if the Karatsu ware with its almost eccentric appearance, such as the Ogu-yaki water jar mentioned above, had been created under his guidance, it is thought that a similar type would have been used at Oribe’s tea ceremony. However, there are no such examples, so it is likely that Karatsu ware, which Oribe favored, was not yet being fired around the Keicho period. Therefore, it is also thought that the Karatsu water jar that Hisashige Matsuya presented at the tea ceremony in the 8th year of Keicho was also a “mimitate mono”. Next, we have a piece of Karatsu ware that shows a strong tea-ceremony style, and what is particularly notable is the angular shape of the tea bowl. This shape is similar to the Setoguro tea bowls that were fired in the Higashi-Mino region around the Keicho period, and the foot ring is also low.

Furthermore, some of these have a double foot ring, and the thick application of white feldspar glaze is very similar to the Shino pottery from the same area.

From these points, it is thought that Karatsu ware had a deep connection with Seto ware. On a Karatsu ware plate, there is an inscription that reads “Enko Dokkoku Renge Roku”, which refers to the story of En En, one of the three famous monks of the Tokei sect, who went into the mountains and planted twelve lotus flowers to tell the time by the shadows they cast on the water’s surface. The fact that this story is also found on Shino ware also shows the connection between Karatsu and Seto.

It is said that the remains of 120 or so Karatsu pottery kilns have been discovered to date, and these kilns are classified into groups such as Kishidake, Matsuura, Taku, Takeo and Hirado. The Kishidake system includes the Hohashira kiln in Kitahata Village, Higashimatsuura County, Saga Prefecture, the Iidouro kiln, and the Donoya kiln in Ouchi Town, also in Higashimatsuura County. Among these, the Hohashira kiln, which fired so-called mottled Karatsu ware with a thick, vitreous white glaze, and the Iidouro kiln, which fired blue-green glaze made from wood ash are known as kilns that produced dignified folk-style pottery, and the blue-green wave-like patterns that often appear on the inside of the pots, which are a characteristic of the Ido-gama kiln, clearly show the lineage of Karatsu pottery, as this method of forming is a technique used in Joseon pottery. The Matsuura kilns are famous for their so-called Joseon Karatsu ware, which is similar to Joseon pottery in that it is glazed in a single color of amber or, in some cases, with a cloudy white glaze, and the Doen kilns are famous for their so-called E-Karatsu ware, which is decorated with elegant black or reddish brown glaze designs. The Taku lineage is said to have been started by the potter Ri Sanpei and his followers, who were naturalized by Taku Jun’an, a chief retainer of the Nabeshima clan. The Koryadani kiln in Nishitaku-machi, Taku City, Saga Prefecture, is well known. The Takeo school was also opened by the potter Soden and his followers, who were naturalized by Goto Ienobu, a retainer of the Nabeshima clan. The Shoko-dani kiln in Takeuchi-machi, Takeo City, and the Kora kiln in the same town belong to this school.

The Hirado school also includes the Kihara-yama kiln in Oriose, Sasebo City, Nagasaki Prefecture, which is known for its skillful use of brush marks.

Karatsu ware, which is classified as part of the Kishidake, Matsuura, and other schools, is generally rough, but the grains are relatively uniform, as is the case with Karatsu clay, which is known as “sand-grain” clay. Because of the high iron content, the color of the unglazed surface of the finished pottery is generally a dark brown or blackish brown, but there are also examples of a light grayish-white color, such as those produced at the Doen kiln in the Matsuura area, the Aboya kiln, or the Fujinokawauchi kiln, and there are also examples of a light yellowish-brown color, such as those produced at the Yamase kiln in the Kishidake area. The glazes can be broadly divided into three types: those made from wood ash left in the kiln, those made from a mixture of ash and feldspar, and those made from iron-based black glazes.

Wood ash glazes are highly transparent, and depending on the difference in the oxidizing and reducing flames, they can become yellowish yellow Karatsu ware, or bluish green, called Ao Karatsu ware. The ash and feldspar glaze is generally opaque white, called “speckled Karatsu”, and is often used in the production of Habori ware.

This glaze is similar to that used in the production of the Hoin kilns in North Korea, and it is thought that Karatsu ware also draws on the traditions of the Hoin kilns.

The next type of glaze, Tenmoku glaze, is widely used in the Karatsu kilns, but depending on the amount of iron contained in the glaze and the nature of the flames, it can either turn black or change to a cast iron color.

Hagi

Hagi ware is also a Korean-style pottery, like the other Kyushu kilns represented by Karatsu ware. According to tradition, it is said that the Korean potter Ri Kei, who had become a naturalized Japanese citizen, founded Hagi ware in a warehouse in Matsumoto village under Hagi Castle during the reign of Mori Terumoto, or that it was founded by Ri Kei’s older brother Ri Gukwang, but there is no definite answer. However, Terumoto entered Hagi in 1604, so it is thought that the ware was founded after that.

At first, Lee Kei was known by the surname of Sakakura, but later changed it to Saka, and in 1625, after receiving a license from the domain to use a different name, he took the name of Koraizaemon. The pottery of Koraizaemon’s grandson, Shinbei Tadasune, used the mountain called Kogaku (also known as Tojinzan) as the source of fuel for firing the kilns, as had been permitted since his grandfather’s time.

The situation was such that the father, Shinbei, was entrusted with the duty of looking after the mountain, and would report to the lord of the domain when he was carrying out his duties.

However, he was given a small stipend of rice by the domain, and continued to make pottery on a small scale.

Meanwhile, Hirashiro Mitsutoshi, the grandson of Ri Shakko, who later took the surname of Sakakura, and Shakko’s pupil Gorozaemon Kurasaki, moved to the area of Mikunose in Fukagawa-cho, Otsu-gun, where Ri Shakko is said to have died, and opened a pottery there.

In relation to the opening of the kiln in Fukagawa, the letter of transmission (a manuscript dated after the 9th year of the Kyoho era) from the father of Hishiro Mitsutoshi, Shinbei Mitsumasa, states

I have been appointed as the official kiln master on the 7th day of the 4th month of the 3rd year of the Meireki era. I have been granted a letter of appointment to travel to another country, and I have also been granted a letter of appointment to travel to another country, and I have also been granted a letter of appointment to travel to another country, and I have also been granted a letter of appointment to travel to another country, and I have also been granted a letter of appointment to travel to another country, and I have also been granted a letter of appointment to travel to another country, and I have also been granted a letter of appointment to travel to another country, and I have also been granted a letter of appointment to travel to another country, and I

In addition, the letter of request that Kozaki Gorōzaemon presented when he moved to the Fukagawa area states

…from Komakasako in Sōnozeyama, we have been granted permission to burn wood for pottery…we have been granted permission to use timber…we have presented the contract as above

and is dated July 25th, 1656. From these records, it can be inferred that the Yamamura family moved to Matsumoto and opened a pottery around the beginning of the Edo period, during the Meireki and Jōō eras. After that, the Miwa and Saeki kilns were opened in Matsumoto, and the Sonose and Furuhata kilns were opened in Fukagawa.

As is said in the Genroku era, “The Hagi ware of old was fired in Matsumoto and Fukagawa, as is said in the following passage: ‘The Hagi ware of old was fired in Matsumoto and Fukagawa, as is said in the following passage: ’The Hagi ware of old was fired in Matsumoto and Fukagawa, as is said in the following passage: ‘The Hagi ware of old was fired in Matsumoto and Fukagawa, as is said in the following passage: ’The Hagi ware of old was fired in Matsumoto and Fukagawa, as is said in the following passage: ‘The Hagi ware of old was fired in Matsumoto and Fukagawa, as is said in the following passage: ’The Hagi ware of old was fired in Matsumoto and Fukagawa, as is said in the following passage: ‘The Hagi ware of old was fired in Matsumoto and Fukagawa, as is said in the following

Many examples of this Hagi ware are tea bowls, water jars and other tea ceremony utensils. The style of these pieces is similar to that of the Yi Dynasty pottery of the Ido, Kumagawa and Gohon kilns, which is to be expected given the origins of Hagi ware, and so the old-style shards are very similar to those of Karatsu ware. However, it is said that the reason why these types of Hagi ware that have survived to the present day are not known is because, as is commonly referred to as the “Seven Transformations of Hagi”, old Hagi ware is mixed in with the wares produced at the various kilns in Kyushu, which are also of the Korean style. On the other hand, alongside these Korean-style pieces, there are also Hagi ware pieces with a distinctly Japanese style, such as water jars that look like they have been bent out of wood, and tea bowls with footrests shaped like flower petals, known as “cherry blossom footrests”. The glaze is usually a soft, opaque white, characteristic of Hagi ware, but there are also some pieces with a slightly thicker glaze, known as “oni-hagi” (demon Hagi). The clay is also soft and gentle, just like the glaze. This is said to be because the clay is taken from Daidōdōzan in Hofu City, but it is said that Daidō clay was first used for Hagi ware in the mid-Edo period, around the Kyōhō era. Therefore, it can be said that this type of Hagi ware was fired after that time.

Shigaraki and Asahi

Shigaraki ware was fired in Nagano and Kamiyama villages in Koga County, Omi Province. According to tradition, it was created during the Tempyo-hoji era, but its origins are unknown.

At the beginning of the Taisho period, a cylindrical kiln with a lid shaped like a shamisen plectrum was excavated in Sasayama, Toki Village, Toki County, Gifu Prefecture, in an area commonly known as Sakurado. The clay is coarse, with white pebbles mixed in, and has a shiny reddish-brown color, and although it is thought to be Shigaraki ware, it is the same as the clay surface. The style of the floating pattern of the cherry blossoms and the sparrows on the accompanying round mirror is thought to be a Japanese mirror from around the end of the Heian period, so it is thought that this pottery was also fired around that time.

From examples like this, we can say that Shigaraki ware was being produced at the end of the Heian period, but the Kamakura period that followed is unknown, and only a few examples from the end of the Muromachi period are known.

This example is a jar excavated from Nagano-bo-yama, and the date “Chouroku 3, March 10” is written in ink on the lid, which is a bowl with a spout – a grayish-brown Sue ware – so the firing date of the body is also estimated to be around that time. The clay of this jar is grayish-white, and there are relatively few white pebbles mixed in with the clay, but the surface of the clay is similar to that of dried rice cakes, which is characteristic of Shigaraki ware. In addition, the top edge of the rim is made in the same way as the mouth of a Tokoname ware jar from the Nanbokucho period, with a spout (higuchi). The shape of the mouth of the old-fashioned Shigaraki jars is often similar to that of the bottles made in Seto at the end of the Kamakura period, and they have a wheel-axle shape, but on the other hand, the mouth of the jar excavated from this site is similar to that of a pot, and it is thought that Shigaraki ware was influenced by both Seto and Tokoname ware.

As you can see, there are very few definite examples of old Shigaraki pottery, but the name Shigaraki-yaki appears in the records quite a lot. At the beginning of the Muromachi period, Shigaraki-yaki was mentioned in the same breath as Kōtō (Bizen ware) and Seto ware as a type of pot suitable for storing tea leaves. Also, in the entry for October 18th of the second year of Entoku at the end of the Muromachi period, it is written that “two Shigaraki pots were bought”, and it is thought that they were bought for the same purpose (Kage Ryoken Nikki).

These Shigaraki pots were originally made to serve the needs of the local farmers.

On March 10th, 1570, Tsuda Sōyū held a tea ceremony for Sen no Rikyū, Yamagami Sōji and other famous tea masters of the Momoyama period, and it is said that the “shikaragi oni-oke (demon bucket) that Tsuji Gen’ya owned” was originally a tool used by farmers’ wives to spin thread from cotton.

According to research by Mr. Yasuda, the first time that Shigaraki ware, which was a type of folk craft, appeared as tea utensils was on the 7th of the 4th month of the 18th year of the Tenbun era, when a water jar was used at a morning tea ceremony held by Hyogo Shimoma, a priest at the Ishiyama Temple in Osaka. However, examples of Shigaraki ware being used at tea ceremonies were relatively rare at this time, and it was not until the middle of the Tensho era that it began to be used more widely. The majority of these vessels are simply referred to as “mizusashi” (water jars), but in the Keicho period, they were often used with matching lids, as can be seen in the case of the “Tomobuta” Shigaraki mizusashi used in the tea ceremony held by Furuta Oribe on November 20th, 1609, to introduce the Shigaraki tea caddy with a high, bulging shoulder. Also, one day later, on the 21st, Kosho Kobori (Enshu) used a Shigaraki water jar with a matching lid at a tea ceremony he held in Fushimi, Kyoto (Matsuya Kyukokai Ki). Furthermore, at the tea ceremony held by Sakuma Funsai Nobumori in 1603, Shigaraki water jars and tea bowls were used. From these examples, it can be thought that Shigaraki ware was being fired for use in tea ceremonies as well as for daily use at this time.

It is also recorded that Shigaraki water jars were used at a tea ceremony held by Oda Saemasa (the fourth son of Oda Urakusai Nagamasa) in Yamato-kaishu (Sakurai City, Nara Prefecture) in February of the third year of the Shouho era, and a rough sketch of the jars is shown (Matsuya Hisashige-kai Ki). Looking at it, the shape is similar to a pacifier that babies suck on, and next to it it is written “Gokufuki”, so it is imagined that the Shigaraki water jar from around the latter half of the Keicho period was a shape with a strong tea aesthetic.

Also, the foot of the Shigaraki tea bowl with the “Mizunoko” signature, which was said to have been treasured by Kobori Enshu and was famous from an early stage, has a polygonal shape similar to that of Raku tea bowls, and the glaze from the back of the foot to the waist and the glaze that runs from the foot to the waist of the cup, which is reminiscent of the so-called “fuse-yaki” style, suggest that Shigaraki tea bowls from around the Keicho and Genna periods also strongly expressed a tea-consciousness.

In this way, Shigaraki ware was widely used by tea masters from the Momoyama period to the early Edo period. As a result, tea bowls called Rikyu Shigaraki and Enshu Shigaraki, which reflected the tastes of famous tea masters of the time, were created. On the other hand, the simple beauty of Shigaraki pottery, which was so admired by tea masters, gradually disappeared as the tea bowls were fired, leading to the decline of Shigaraki ware.

Asahi-yaki is listed as one of the seven Enshu kilns, along with various kilns in places such as Zeze (Omi), Kosobe (Settsu), Akahada (Yamato), Shidoro (Tome), Ueno (Buzen), and Takatori (Chikuzen). However, the history of the kiln is not well known. According to tradition, it was started by Okumura Jiroemon, a man from Uji, around the end of the Keicho era, but it was discontinued around the beginning of the Edo era, during the Shoho and Keian periods, and was restarted by Okumura Tosaku around the Joushou period. Another theory is that Okumura Tohei, a man from Omi, opened a pottery around the time of the Shoho era, and his son Tozaku took over, but that the pottery stopped around the time of the Kanbun era. Since Kobori Enshu died in February of the fourth year of the Shouho era, if we assume that the kiln was opened during the Shouho era, as the latter theory suggests, then it is likely that it was related to Enshu’s son, Gonjuro Masayoshi, who is said to have given the Asahi mark.

The kiln site is at the foot of Mount Asahi, and it is said that tea utensils were made using the soil from this mountain, and in particular, it is said that tea bowls were fired exclusively, and as such, tea bowls can be seen in the surviving examples. The clay of the old-fashioned ones among them is relatively rough, and as can be seen in the glaze on the pale dark blue surface of the vessels, there are countless small blackish-brown spots, so they were not carefully selected. The shape is similar to that of Korean tea bowls, but with a Japanese twist. The strong marks of the potter’s wheel from the waist to the foot of the bowl, the white glaze that appears on the dark blue glaze, and the clearly-defined whorl pattern on the underside of the foot the clearly-defined raised spiral pattern on the underside of the foot ring, can be said to be a remnant of the style of the so-called Koryo tea bowls, which are also known as Ido or Kugibori Iroha.

Asahi-yaki was revived by Matsubayashi Chobei, a local potter, around the end of the Edo period. The Matsubayashi kiln was located in Yamada, Uji-go, and fired using clay from the Warada area, but the style of the pottery produced there was extremely plain and lacking in elegance, unlike the Asahi-yaki produced before this time.

As is said that Ashikaga Yoshimitsu established seven gardens in Uji and gave some of them to his close retainers, such as the Kyogoku, Yamana and Shiba clans, Uji was known from early on as a tea-producing area. In addition to being used for private purposes, as can be seen from the phrase “Ouji no Hoshino Soi Jikichi Genkenshojosen Todai Gontsuimikikoto Shikakumonochadono Koto Mimasu…”, orders were received from the Imperial Court and other households, and orders were placed with the Hoshino and Kanbayashi families, both of which were famous for their Uji tea. It is likely that this kind of thing stimulated the rise of the old Asahiyaki.

Ninsei

Kyoyaki pottery from the Edo period, which is known for its elegant style, began with Ninsei, and Ninsei’s works show the highest level of this style. Therefore, Ninsei’s pottery style became the benchmark for Kyoyaki pottery from that point on, and it was passed down for a long time.

Ninsei was from Nonomura in Kuwata-gun, Tanba Province, so he took the surname Nonomura and his first name was Kiyoemon. The reason he took the name Nonomura is because there is a fragment of pottery excavated from the site of Nonomura’s kiln in Omuro that bears the inscription “Nonomura Harima, 1656”, so it is thought that he took this name from that time onwards. Until then, he was known as Tsuboya Kiyoemon and Tanba-yaki Kiyoemon. Also, when Nisei was young, there is a legend that he dedicated incense burners to three temples, including Ninna-ji, Yokoo-ji, and An’yo-ji in Oharano, Ukyo-ku, Kyoto, in the hope that his skills would improve. The incense burner is inscribed with the words “Dedicated by Nisei, a Buddhist priest, in the third month of the fourth year of the Meireki era”, so it is thought that he was using the name Nisei at this time. Furthermore, it is thought that he took the name of “Nyudo” (monk) around this time because his good mentor, Kanamori Sowa, had passed away in December of the previous year (1656).

In August of 1678, Morita Kyuemon, a pottery maker from Odo in Tosa Province, visited Omuro on his way to Edo. His account of the visit says, “I also visited the kilns. There are seven of them, and the potter is a man named Nonomura Seiemon.” He does not refer to the potter as Nisei. However, a loan certificate from the previous year, dated 1676, shows that the borrower was Kiyoemon, and that Ninno was the guarantor. This suggests that Ninno had already handed over the family business to his eldest son, Kiyoemon Masanobu, at that time. However, in 1695, when the Maeda family of Kaga ordered Omuro-yaki incense containers through the Urasenke school, they received a reply from Urasenke saying, “…we have made thirteen Omuro-yaki incense containers, but they are all extremely poor quality and unsuitable…Ninsei has now become the second generation…” This is recorded in a memorandum by Maeda Sadachika, a samurai of the Kaga clan. The fact that Nakano Sowa, who was the teacher of Ninshō, and the Maeda family had an extremely close relationship can be inferred from the fact that Sowa’s eldest son, Shichinosuke, was taken into the Maeda clan at the age of 16 in 1625 with a large stipend of 1,500 koku. It is thought that this relationship was one of the reasons why the Maeda family commissioned the incense containers of Nonomura Ninsei’s Omuro ware, which were under the guidance of Souwa. However, it is said that the second generation Kiyoemon was the one who made the Omuro ware, and it is thought that Ninsei had already died by 1695. However, the exact age of Ninsei’s death is unknown.

Ninsei built a kiln in front of the gate of Ninna-ji, a famous temple in the Rakusai area, and produced pottery there. After the Onin War, Ninna-ji had fallen into a state of great disrepair, but the third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu, appointed Awaji-no-kami Kinoshita and Kai-no-kami Aoki as construction commissioners to oversee its reconstruction, and it was completed in 1656. And in the same year, in October, Prince Kakushin, who was the 21st head priest of Ninna-ji Temple, moved from his temporary residence to the new palace, despite being the first son of Emperor Goyozei. The priest Kensho of the temple’s sub-temple, Sonjuin, who made great efforts to rebuild Ninna-ji Temple, described the scene of the move in October in the following detailed account

Ninna-ji Temple Relocation Diary

On the 11th day of the 10th month of the 3rd year of the Shouho era, the relocation of the new imperial palace from the Honjo area to the Ninna-ji Temple area took place in the early hours of the morning. The following is a brief account of the procession, etc. The four people who rode in front of the procession were non-official attendants, and they were the young boy, the middle-aged boy, the older boy, and the priest. the four-legged east gate, the middle gate, the central room on the east side of the main hall, and the monks’ quarters. The other monks, including the head monk of the temple, are ordered to go to the south gate and wait inside the gate. Today, the monks will be working on the various halls and the imperial palace. The temple supervisor has been asked to prepare food for the imperial palace. On the day of the auspicious occasion of the transfer, the place of the transfer will be the same as the one indicated on the same day, and although the transfer will be carried out today, it will be carried out at a later date. At the same time, the transfer will be carried out at a later date. At the same time, the transfer will be carried out at a later date. At the same time, the transfer will be carried out at a later date. At the same time, the transfer will be carried out at a later date. At the same time, the transfer will be carried out at a later date. At the same time, the transfer will be carried out at a later date. At the same time, the transfer will be carried out at a later date. At the same time, the transfer will be carried out at a later date. At the same time, the transfer will be carried out at a later date. At the same time, the transfer will be carried out at a later date. At the same time Uemon have also been summoned. The two magistrates have also sent one silver coin each. The two magistrates have also sent one hundred bronze coins each. The sake cups and the congratulatory gifts have also been prepared. The five fruits have been offered according to the old custom. After three days, the living spirit will be buried.

According to this, the four people who ran ahead were not in any official position, so it seems that they were people who served on a temporary basis and out of goodwill, and it is also known that the ceremonial children were borrowed from Ishiyama-dera, and while it is said that the order was to keep things as simple as possible, the fact that the ceremony was held in this way was probably due to the fact that Ninna-ji’s finances were in a tight spot. Anyway, since the reconstruction of Ninna-ji was completed, it is thought that the surrounding area regained its former prosperity.

In the diary of Hourin, the sixth son of Kanju-ji Haruhiro, who was born in 1593 and died in 1668, it is written that “the people of Kamo no Seki came to the tea ceremony room of Omuro to receive a tea caddy”. At the time, Nisei’s pottery was also known as Nisei-yaki and Ninnaji-yaki, but Omuro-yaki was the most widely used name. On January 7th, 1663, a man named Yugao Uemon – a cosmetics dealer? , and also from the fact that the “Saga Kōjō” guidebook, which is said to have been published around the time of the Enpō era, states that “there is a pottery house in front of this gate in the modern era, and it is called Ninshō… The Omuro-yaki tea bowls and tea caddies that tea ceremony masters now enjoy are these…” we can see that Ninshō-yaki was Omuro-yaki.

As such, it is thought that Ninnaji was rebuilt and Prince Kakushin moved there in October of the third year of the Shoho era, and as the first mention of the name Omuro-yaki is in January of the fifth year of the Shoho era, it is thought that Ninnaji was opened in the middle of the fourth year of the Shoho era (1647).

The reason for Ninshō opening a pottery in front of Ninna-ji Temple may have been the fact that it was a newly developed area due to the reconstruction of Ninna-ji Temple, as mentioned above, but it is also likely that Hōrin helped him. Hōrin was very trusted by the retired Emperor Gosuiō, and he often visited the retired Emperor’s residence at the Sento Palace to play renga (poetry) and sugoroku (a board game).

In addition, in December of the fourth year of the Kanbun era, the retired Emperor Gosui was said to have opened a kiln for firing pottery at the Shugakuin Imperial Villa, and he ordered him to accompany him, so he attended despite being ill and the cold weather. Therefore, it is thought that he was also close to Prince Ninnaji no Miya Kakushin, the older brother of the retired Emperor Gosui. In 1662, a lumber merchant from Edo called Fushimiya Chouemon visited Hourin and asked him to help him sell lumber for the repair of Ninna-ji, so the fact that Hourin wrote a letter to the Ninna-ji official in charge of the Omuro area is an example of the relationship between Ninna-ji and Hourin. The fact that Hōrin wrote in his diary in August 1645, “The potter Seiemon made pottery in the shape of… I also made a water jug, plates, tea bowls, etc.” suggests that Ninshō was close to Hōrin. Therefore, it is thought that Hōrin may have helped to arrange things, and it is also thought that the result of this was the opening of the Omuro kiln by Ninshō.

Looking at the world of Kyoto pottery at the time, there were kilns in Awataguchi, Yasaka, Nijō Oshikōji, etc., and the records show that the items fired there are recorded. In April 1704, Horin visited the potter Seibei, who lived in Yasaka, with the guidance of the Chinese goods dealer Ohira Gohei. After seeing him making tea caddies, incense containers and incense burners on the potter’s wheel, Horin walked to the mountains and also saw the kilns there. Three years later, in the first year of the Shoho era, Horin presented a kougei to Funakoshi Gaiko, a retainer of Hojo Hisada, the feudal lord of Kawachi, on his return to his home. This was a wisteria-shaped piece made by the potter Seibei, who had come to the area the previous year, and it is said to have been covered in a mixture of purple and blue glaze. From the glaze, it can be imagined that the incense container that Horin presented was Yasakani ware, a soft pottery similar to Koji ware. Therefore, it can be said that the Awataguchi ware was also of the same type of soft pottery. There were also kilns in Kiyomizuzaka, Otowayama, and Mizoroidake, but there is no information about these.

On the other hand, at the time, pottery from various regions was being imported to Kyoto. These included pottery from nearby places such as Omi (Shiga Prefecture) and Owari Seto, and from more distant places such as Imari, Higo ware and Buzen ware. These were different from the soft pottery made in Awataguchi and Yasaka, and were hard and highly practical, so it is likely that the interest of the tea ceremony enthusiasts in them was also high. The fact that Horin often gave Imari ware as gifts to the retired emperor and his acquaintances is one indication of this trend. The fact that the interests of Kyoto’s tea ceremony enthusiasts were moving in this direction may have been one of the reasons that Narihira did not make soft-paste ceramics. It is also possible that it was more appropriate to build a kiln in Omuro, a location away from the center of the city, rather than building a kiln with seven ovens in a place like Awataguchi or Yasaka, as described in the Kueemon Diary.

On March 25th, 1645, a tea ceremony held by Kanamori Sowa in Kyoto is mentioned in the diary of Matsuya Hisashige, a lacquer artist from Nara. He describes the “arayaki” – a new type of pottery – water jugs he saw there as being of the Ninnaji ware style, with a square-shaped body and cut-out shapes.

Sowa was the eldest son of Kanamori Kazushige, the lord of Hida Takayama, but he is said to have disagreed with his father over the Osaka campaign of the Keicho and Genna periods, insisting that he would not take part in the campaign, and was disinherited. After that, he is said to have gone to Kyoto, where he studied Zen under Daitokuji’s Denso Soin, and took the name Sowa. As a tea master, he was widely known among the aristocracy of the time. Regarding the fact that he had many close friends among the nobility through his tea, the tea master Koan Yamada claims that Sowa was spying on the movements of the court at the time on behalf of the Tokugawa family. Be that as it may, his tea style is said to be very elegant, as is the case with the so-called Princess Sowa. However, if we look at the jar made by NINSEI, which is similar in shape to a water jar, as mentioned in the above-mentioned diary by Hisashige Matsuya, we can see that both the shape and the glaze have a deep, elegant beauty. Therefore, it cannot be said that the tea style of SOWA was always elegant.

The fact that Nisei went to Kyoto to study when he was young, and then went on to the Seto region to further hone his skills, is recorded in a book of pottery techniques that was passed down from Nisei’s second son, Seijiro Fujira, to Ogata Kenzan. The legend that he learned how to make tea caddies in Seto from Takeya Genjuro is also thought to have originated from his time studying in Seto. According to this book of pottery techniques, it mentions the names of various colors that were used for tea caddies, such as persimmon-colored, metallic-colored, and Shunkei-colored glazes, as well as “Beni-sara-te”, “Seto-aoyaku”, and “Seto-kannyu-te”. Seto-aoyaku is a copper-colored glaze that was often used in Oribe ware, and “kannyu-te” is thought to refer to the glaze used in Shino ware. Also, although it is not clear, it is thought that “Benizara-te” may have been yellow Seto, which was popular at the time along with Oribe and Shino.

Now, although the remains of Nisei ware are designed to burn incense, such as the ones made of zako and horagai, there are also some unusual-looking ones, such as those that are designed to be displayed in tokonoma alcoves or to hide the nails of the beams in a room. However, the most common items are tea utensils, including jars, water jars, tea bowls, tea caddies and incense containers. The jars that represent Nisei pottery are thought to have been displayed at tea ceremonies, and their shape is that of the so-called Rouso jars that were imported from China from the end of the Muromachi period and called “shin-tsubo”, “seika-tsubo” and “renge-ou”. Since Rouso-tsubo were considered suitable for storing tea leaves and were highly prized from early on, it is thought that Ninshou-tsubo were modeled on their shape, but there are also some that are different, such as the aforementioned shape with a square body. The exterior is covered in white glaze with polygonal cracks, called renzenkanninuki, but the bottom is left exposed, with the so-called “tucking up the hem” technique.

The shapes of water jars are more diverse than those of vases, and include elegant shapes, barrel shapes, and gold dust bag shapes. In addition, they have richly varied ears, such as bamboo-scraper-shaped, bracken-shaped, and knotted-cord-shaped ears on the body. Some of the pots, such as those known as Ninshō Shigaraki, make use of the natural taste of the clay, but in addition to Shigaraki-style mizusashi, there are also Nanban-style mizusashi, and there are also many different types of mizusashi that make use of this natural taste, just like the shapes.