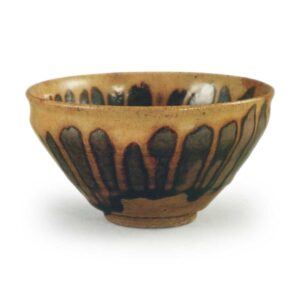

Chuko Meibutsu

Collection: Fujita Art Museum

Height: 6.6cm

Diameter: 12.2cm

Foot diameter: 4.7cm

Height: 0.6cm

This is a type of Seto Tenmoku, and the inside and outside of the bowl are covered in a thick, dark brown glaze from the rim down to the body, and then a yellow Seto glaze is applied to the rim, which flows in stripes inside and out, giving the appearance of chrysanthemum petals, and so Kobori Enshu named it Kikka Tenmoku.

The areas where the two glazes mix together become a yellowish-brown color, while the petal-shaped areas become a metallic glaze. The flowing amber glaze either pools thickly in the interior or flows over the exterior, creating glaze pools in various places, and the design of the chrysanthemum is the main focus, but the variations in the glaze surface are endless, despite the simple technique used.

The rim is modeled on the flat rim of Tenmoku, but the foot ring is low and wide, a feature shared with Seto Tenmoku from the end of the Muromachi period. The shallow scraping inside the foot ring, the scraping on the side of the foot ring, and the application of cast glaze to the clay-viewing area are also characteristic of Seto Tenmoku.

The chrysanthemum tenmoku is an extremely rare surviving example, and only one other similar piece is known to exist today. However, the Shunkei tea caddy called “yukari-te” is made in the same way as the Kikka Tenmoku, with a yellow Seto glaze applied over a dark candy glaze, and since the maker of the Shunkei tea caddy, Shunkei, was a lacquerer from Sakai around the time of the astronomical calendar, it is thought that this type of technique was being used in Seto at this time.

However, because the number of Kikka Tenmoku pieces that have survived is extremely small, it is thought that they were probably only made in specific numbers, depending on the preferences of the owner. Even in the Muromachi period, there were so-called “numbered” pieces of Seto tea caddies that were only made in specific numbers, so it is thought that Kikka Tenmoku pieces probably belonged to this category.

For this reason, it has been prized as a rare piece of Seto Tenmoku since ancient times, and it was written about in the “Enshu Zocho” (Enshu’s Tea Bowl Inventory) and also mentioned in tea books. For example, in “Merekusa”, it is written, “The same feeling as the chrysanthemum Tenmoku and the Hakuan Tenmoku, the inside of the Tenmoku has a pattern of chrysanthemum flowers using metallic glaze, it is extremely splendid, and it is thought that it should be the same as the Hakuan Tenmoku”, and it compares the glaze with the Hakuan Tenmoku, considering the style of the period to be the same as the Hakuan Tenmoku.

Also, in “Meibutsu Merekisha”, it is written, “Chrysanthemum Tenmoku Kobori. It is said to be equal to Seto Hakuan, and the inside and outside are covered with chrysanthemum-shaped patterns, and the rest is covered with yellow Seto glaze. It is said to be used for Souho light brown tea.

In short, Kikka Tenmoku has been highly regarded as the finest of all Seto Tenmoku since ancient times, and the rarity of the surviving pieces adds to its reputation. The main attraction is, of course, the magnificent chrysanthemum design that shines out against the vivid yellow Seto ground, and it is for this reason that Enshu valued it so highly, naming it “Chrysanthemum Tenmoku”. The striking contrast between the yellow and the gold is striking and appealing, and it is very distinctive in the world of Tenmoku, which was shrouded in the darkness of the Middle Ages. This feeling could be said to be the first sign of the dawn of the Momoyama period.

The glaze pool, which is a promising amber color, is also very attractive, and the stone spatter in the center adds to the beauty of the piece. There are two small and one large repair on the rim, and a vertical crack runs down the center. There is a splash of glaze on the foot ring, and a glaze pool can also be seen on the side of the foot ring.

Transmitted from generation to generation. It is written in the Kobori Enshu box and appears in the “Enshu Zocho” (Enshu’s inventory of his possessions), and it was in the Kobori family’s possession, but in the fourth year of the An’ei era, when it was in the possession of Kobori Izumi no Kami, it left the family and passed into the hands of Matayoshi of Osaka, and later it was passed down to the Matsudaira family, the feudal lords of Ueda in Shinano. In the first year of the Taisho era, when the Matsudaira family put it up for sale, it came into the possession of the Osaka Fujita family, and later, when the Fujita Art Museum was established, it became a museum piece.