Jomon is a pattern applied to earthenware by using a large twisted string as the base material for the decoration. It can be broadly classified into the following categories: pressed, rotated, stick-wrapped pressed, and stick-wrapped rotated rope. Other types of rope patterns include pseudo-nawa and nawa-me. The linear rope pattern is a design in which a twisted cord is pressed against the surface of the vessel. Many of them are based on a single-strand twisted cord, i.e., two (or three) twisted strands of twisted fiber bundles twisted together in a twisted twisted form. Right- and left-handed twists are sometimes pressed side by side or in spirals. Rotating rope patterns are applied by stamping the twisted cord on the surface of the vessel while rotating it. The name “oblique” (斜行) Jomon is also used, since the stripes often run diagonally. It is also often referred to simply as Jomon. The most common type of rotary Jomon is a two-tiered twisted cord made by twisting two (or three) single-tiered cords together, and is composed of many independent sections in which the oblique strips of the Jomon are arranged in succession (single-tiered oblique Jomon).

When a three-tiered twisted cord is used, the rope is further divided into two or three knots (compound strand oblique rope), and when a one-tiered twisted cord is used, there are no knots visible in the strands, only fibers running along the strands (knotless oblique rope). In addition, by further twisting right- and left-twisted strands together, or by creating a more complex base, such as wrapping another twisted strand around the axis of a twisted strand, many other types of rotary rope patterns can be created, including those with different shapes of segments (i.e., different segmented oblique rope patterns) and those with different shapes of adjacent strips (i.e., different strips of oblique rope patterns). The shape of the twisted cord can also be different from that of the end of the twisted cord or the end of the twisted cord. Other types of rotary rope patterns include those in which a loop is made at the end or in the middle of a twisted cord, and those in which the knot of the twisted cord is rotated and stamped (nodular rope patterns). For the sake of convenience, we have also included those using four-strand braided cords, although they are not twisted cords, in kaiten-jomon. When right- and left-twisted twisted cords are rotated and sealed in the same direction, two types of oblique rope patterns with different slopes are formed, giving them a twilled Japanese cedar shape (hanyu-jomon). These two strands may be joined together in advance to form one original piece. For example, a right-twisted twisted cord is rolled up and down, and the same twisted cord is rolled left and right next to it, producing a kind of feather-shaped rope pattern. After applying the rotary rope pattern, one side of the rope pattern is polished away to create a contrast between the rope pattern and the blank area. The name “Moshi-moshi Jomon” is also used for a piece that has a line drawn in advance and then only one side of the line has a Jomon pattern applied to it. The bar-oshi Nawabumi (kakujo surikeshi obi oshimentsumi) is a twisted cord coiled around a shaft and pressed as it is, and the Nawa-maki rotary Nawabumi is the result of a rotary pressing of this cord. Like the pressed rope pattern, this pattern is called the twisted thread pattern because it produces side indentations on the twisted cord. There are many types of twisted thread patterns, including reticulated twisted thread patterns, wood grain twisted thread patterns, and plain weave twisted thread patterns. The direction of application of rotary and pole-rotary rope patterns can be classified as horizontal (horizontal) or vertical (vertical), with the original body placed horizontally. In both cases, the stripes are oblique. In addition, some vessels are turned diagonally to make the stripes vertical or horizontal. If the surface of the vessel is flexible or if the twisted cord is rolled while pressing hard against the surface of the vessel, the adjacent stripes and joints of the rope pattern will be tightly pressed together, giving the vessel the appearance of a fabric being pressed together. On the other hand, if the surface of the vessel is very dry or if the surface of the vessel is lightly pressed when applying the technique, there will be a gap between the stripes and knots, and the knots will be rounded. There are many types of Jomon, but it is mainly in the Early Jomon earthenware of the northern Kanto region that a wide variety of special Jomon styles developed, while other special Jomon styles are found only in specific periods and regions. Single-strand oblique Jomon using two-strand twine is the most common type of Jomon both nationally and temporally. In western Japan, Jomon disappeared after the end of the Late Period. In eastern Japan, on the other hand, Jomon continued to be used into the Yayoi period and beyond. There are two theories regarding the origin of Jomon, one says that it started out as a decorative pattern, and the other says that it was created to smooth the surface of earthenware and later became a decorative pattern. Recently, however, earthenware from the first half of the pioneer Jomon period has been discovered, and it has become clear that the first Jomon decoration was created by pressing down on a twisted cord, and then rotating the cord while pressing down on it. Jomon has been found in many parts of the world since prehistoric times, and rotary Jomon is still used today in Africa. However, it was not until the Jomon pottery of the Stone Age in Japan and the late Neolithic (Schnurkeramik) pottery of Central and Northern Europe that Jomon became the representative pottery pattern of a culture. However, the main type of overseas Jomon, including European Jomon pottery, is the pressed-pressure Jomon, and the rotary Jomon is very rare. The distinctive feature of Japan’s prehistoric Jomon is the remarkable development of rotary Jomon and stick-rotary Jomon. Pseudo-Jomon is a pattern that imitates the Jomon pattern using a material other than twine. Jomon earthenware imitates Jomon by rotating and imprinting scrolled shells such as Hennatari, or by imprinting shells with a projecting dorsal rib like the high mussel. The rope pattern was made by pounding earthenware or roof tiles with a plate wrapped with twisted cord, which at first glance looks very similar to the Nawa-maki rotary rope pattern, and some people mistakenly think of the same application method. Some people mistakenly believe that this is the same method of application. In Japan, rotary Jomon was long thought to be the result of the imposition of textiles and other materials, but in 1931, Yamauchi Kiyoo was the first to elucidate the method of rotation, which greatly contributed to the chronological study of Jomon pottery and the establishment of a chronological and regional order.

Jomon-style earthenware

Prehistoric earthenware from Japan. The name comes from the use of Jomon for decoration. However, there are many Jomon earthenware without Jomon decoration. In particular, newer Jomon earthenware from western Japan does not have Jomon. On the other hand, in eastern Japan, Jomon is widely used on Yayoi and Sequential Jomon earthenware. Therefore, the presence or absence of Jomon patterns is not an immediate criterion for determining whether a piece is Jomon pottery or not. The areas where Jomon earthenware was used range from Hokkaido in the north to Okinawa in the south. The Jomon period is the period following the pre-Jomon period and preceding the Yayoi period, and its culture is called the Jomon culture. There used to be a theory that the transition from the Jomon to the Yayoi period was different in eastern and western Japan. Today, however, there is no dispute that the transition took place without significant differences in age throughout the country. In the Jomon period, people used stone tools, and based their lives on gathering edible plants, hunting, and fishing. Recently, some people claim that agriculture began in the Jomon period. In Japan, however, it is the Yayoi period that corresponds to the stage of food production in which agriculture decisively revolutionized society and culture.

The Jomon period was still basically a food-gathering stage.

Jomon earthenware varied greatly from one period to the next, and also differed from region to region. The study of Jomon pottery and Jomon culture is based on the chronological study of the Jomon pottery type as the smallest unit of time and space, and on the chronological sequence and regional distribution of the pottery, i.e., chronological research. The Jomon period is thus divided into more than a dozen regions throughout Japan, each of which is composed of 70 to 80 pottery types, which are roughly classified into six periods: Early, Early, Middle, Late, and Late Periods. The names of the pottery types, which now total more than 1,000, are based on the names of the sites where they were first recognized. For example, the Kaseri E and B types were named based on the earthenware from points E and B of the Kaseri Shell Mound, respectively. Moroiso A, B, and C formulas and Angyo III A, II B, and III C formulas are subdivisions of the Moroiso and Angyo III formulas, respectively, using letters of the alphabet. Fukuda C type refers to the middle stage of Fukuda shell mound, and Fukuda K II type and Kurodo B II type refer to the second late stage and second late stage of the Fukuda shell mound and Kurodo site, respectively. This is a convenient way to name many types of pottery from the materials at a single site. The principle of naming pottery types lacks uniformity, but each has its own scientific history, and it is not possible to immediately change the name to a more rational designation.

The actual age of the end of the Jomon period can be dated to 300~200 B.C. based on the age of continental artifacts brought in around the beginning of the Yayoi period. The theory A accepts the radiocarbon measurements as they are and endorses the 8,000 B.C. theory, giving Jomon pottery the title of the world’s oldest earthenware. The B theory estimates the age by comparing continental artifacts that can be dated to the Jomon period with artifacts from the early Jomon period, and places the beginning of the Jomon period between 2500 and 2000 B.C. This theory is based on the comparison of continental artifacts that can be dated to the actual age of the continent.

This theory is weak in that the most reliable materials with a clear date are scattered in faraway Europe. We hope to find good comparative data in East Asia.

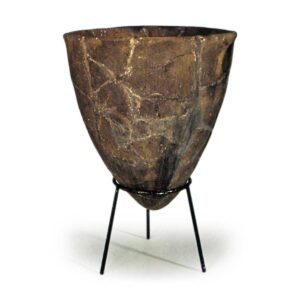

The Jomon pottery of the Pioneer and Early Jomon periods consists mainly of deep bowls, especially pointed-bottomed earthenware.

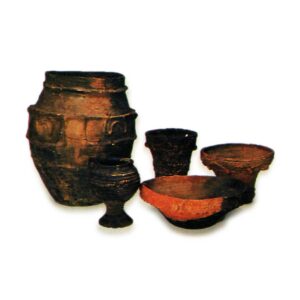

The type of pottery often consists of a single vessel type and is almost exclusively decorated with a single type of decoration. These deep-bottomed vessels are often discolored by heat from fire. Thus, it is clear that Jomon earthenware started out as containers used for boiling and cooking, and it shows the character of food-gathering people’s earthenware. The use of unmarked earthenware in addition to decorated earthenware began already in the pioneer period. This is particularly evident in early examples from the Seto Inland Sea region, where the earthenware type is composed of small, thin-walled pressed earthenware and large, thick, unmarked earthenware (Huangdao style earthenware). The majority of the earthenware from the early period also consists of deep bowls, but many variations of design occur within the same type of deep bowl. Shallow bowls are also rare. Deep pots still dominate the pottery of the middle period. In addition, there are shallow bowls and pedestals, and jars appear at the end of the period, with many changes in the decoration of the deep bowls. The most notable types of pottery from the middle period are those with numerous small holes under the mouth rim and a band of small holes under the rim, which have been interpreted as drums in comparison with pottery examples in folklore and European prehistory. There is another theory that it was used for brewing alcohol. In the later stages of the Jomon period, the types of Jomon pottery became more diverse. Various variants of deep and shallow bowls were produced, as well as pouring jars, tsurite earthenware, incense burner type earthenware, and other types of vessels. In the Tohoku region, jars are quite common. The most striking feature, however, is that deep pots for boiling and cooking were clearly distinguished from decorated earthenware with other functions, and were established as a type of vessel with little decorative value. While the Yayoi earthenware of the northern Kanto region, which is closely related to Jomon earthenware, has been left aside, the Yayoi tradition is still being used in the Kitakyushu region, Wakayama Prefecture, and the Ise Bay coastal region. In the Late Period, Kamegaoka earthenware from northeastern Japan is famous for its large number of vessels. There are also many jars. In western Japan, deep and shallow bowls are the basic types of pottery, but jars are rare. There are few specific examples of the uses of vessels other than deep pots used for boiling and cooking. However, the existence of earthenware with numerous holes in the bottom suggests that it was used as a filter (Nakamura Kozaburo and Teramura Mitsuharu, “Jomon Culture ni okeru Jeungsangen-doki,” Archaeological Magazine, 42-1). The use of earthenware as a coffin is well known for Yayoi pottery, but Jomon pottery was also often used as a coffin for the burial of fetuses and newborns, and there is a case (early in the late Tohoku region) where adult bones were placed in a coffin, suggesting that the custom of reburial, or collecting bones after burial and then re-burial, was practiced. The Kamegaoka style’s numerous types of vessels and variety of decorations can be interpreted in terms of their connection to witchcraft and taboo by comparing them with folk examples (Kiyotsuki Tsuboi, “Jomon Culture Theory,” Nihon no Rekishi [History of Japan], 1). Note that lids appeared in the Tohoku region (Okijushiki) at the end of the middle period, spreading to the Kanto and Hokuriku regions in the late period, and remaining in the Hokuriku and Kinki regions until the late period.

In the Kanto region, earthenware with lids and bracelets made of shell were also excavated, showing an example of the use of lidded vessels. Sand grains are generally recognized as admixture. Special admixtures include mica (e.g., Kanto-middle Agudai style) (this example is said to have been mixed with sand containing mica), beryl (Kyushu early Sobata style, mid Namiki style), graphite Jomon pottery (late), Jomon pottery (mid) (Gifu Prefecture early Oshi pattern pottery), shell fragments (Kyushu mid Agaka style and others), twisted cord (Hokkaido early Musiri style). The mixing of plant fibers has already been done with grasses.

The admixture of plant fibers in earthenware already began in the first half of the Paleolithic period, with the presence of micro-ridge line patterns. Although it is unclear whether or not this is related to the early Paleolithic, a small amount of fiber admixture began in the latter half of the Early Period (Tadokami and Kibokuchi styles in southern Kanto), and by the end of the Early Period, a large amount of fiber admixture was widespread in eastern and western Japan (Kayasan style, etc.), extending into the Early Period. However, many of the fibers found in large quantities in early Jomon pottery run parallel to the vessel walls, so they cannot be immediately considered as mere admixture. The basic technique of Jomon earthenware production is the piling up of clay cords. The absolute majority of the Jomon earthenware, including those of the Inaridai style of the pioneer period in the southern Kanto region and the Tado lower stratum style of the early period, were made starting from the bottom side and extending to the mouth rim. The only known example of pottery that clearly started from the mouth rim is a late Early Iwate Prefecture vessel. There is also a method in which the bottom of the vessel is attached after the body is finished (Kinki Kitashirakawa Shimojo style). Some Jomon-style vessels have indentations on the bottom of the vessel, such as leaves and net-work. Another special example is the indentation of a whale vertebra. All of these are thought to have been used as underlay for the molding of the earthenware. There is also a special example of an earthenware vessel with a leaf shape painted on the bottom. In some cases, the Ajiro bottom was abraded off during the finishing stage. A unique technique for adjusting Jomon earthenware is the use of shell marks. These are marks made by scratching the edges of shells with multiple uneven stripes on their backs, such as the high mussels and salmons, and have several parallel grooves running along the edges. It appeared in the latter half of the early period and became widespread mainly in eastern Japan, but was also found in western Japan in the late period.

There are traces of shell striations made by dragging a Hennatari or other shell on its side. It can be distinguished from the earlier bivalve striae by the fine lines running through the grooves. This type of Jomon pottery was used in western Japan from the end of the Late Period to the beginning of the Late Period. The firing temperature of Jomon earthenware is estimated to be 500~600 degrees Celsius. The firing temperature of pioneer earthenware is hard and comparable to that of Middle and Late Jomon pottery. There does not seem to have been any particular development in firing methods until the Late Period. While Middle Period pottery is generally reddish-brown in color, Late Period pottery is often blackish-brown in color. This is probably due to the final stage of firing, in which a smoldering fire was used to absorb carbon into the surface of the vessels. Some have compared this to the black pottery techniques of the late Neolithic period in China, but there seems to be no relationship between the two. The rules for the application of these late-period patterns have been investigated. On the other hand, there are also some types of earthenware that have been completely free of any designs since their inception, i.e., unmarked earthenware, but there are few types that have been established entirely from unmarked earthenware. Compared to Yayoi and Stone Age pottery from around the world, Jomon pottery is characterized by the fact that the mouth rims are not horizontal, but rather have one to more than a dozen protrusions or a wavy, mountain-shaped mouth rim. Some are limited to the vicinity of the mouth rim, while others cover the entire outer surface of the body, and not infrequently the inner surface of the mouth rim is decorated. The main pattern is found near the mouth rim, and the rest of the body is decorated with Jomon bands. There are also examples of decorations on the outer surface of the bottom, as in the case of Jomon pottery of the early period and Kameoka-style earthenware with sunken patterns. In addition to ordinary sunken and floating patterns, some pieces are coated with lacquer or red pigment, or have patterns painted on them. Red pigment began to be used in the early period (lower Tado style in the southern Kanto region). Most of the materials used were iron oxide, with mercury vermilion being rare. The majority were applied after firing, but there are rare examples of pre-firing application (middle Nagano and late Hokuriku). In addition to black lacquer, red lacquer is also found. Lacquer is concentrated in the Late Period in the Tohoku region, but its existence has also been suggested for the Early Period in the Kanto region. Jomon earthenware is rarely decorated with paintings, but three-dimensional, abstracted representations of animals and humans are found both regionally and temporally. Some of the protruding handles of earthenware vessels depict a face, while others depict the entire human body (or a deity?). Some pottery has a face on one of the projecting handles, while others have the entire human body (a god?) represented. The three-pronged human body, or only the tips of the hands, and snakes are characteristic of Middle Jomon pottery from the Chubu-Kanto region. Some Jomon earthenware has a special form. These include pottery with square or elliptical planes and pottery with two mouths. One of the most famous examples of Jomon pottery that resembles natural objects is that of abalone and mollusks.

Other examples of earthenware with circular mouth rims and square bottom corners are thought to have been made in the shape of baskets (Paleolithic and Late Jomon period).

When Jomon earthenware cracked, it was often drilled on both sides of the crack line and tied with vines or other materials to continue its use. Some of the holes were drilled by prying (Twisted thread pottery from the southern Kanto region), but most of the holes were drilled by turning a stone cone. In addition, there is a known example of Kameoka-style earthenware in which a hole in a piece of pottery was filled with a piece of suitable pottery and fixed with asphalt.