Seto-yaki is a general term for ceramics produced mainly in Seto City, Aichi Prefecture.

Seto has a long history and a thriving ceramic industry, and its name is widely known throughout the world, as the word “Seto” has been used to refer to ceramics since ancient times. This is due to the fact that Seto was located in a naturally favorable area blessed with sufficient raw materials, which was the first requirement for the pottery industry, and also because of the extremely old tradition of the technique and its relatively close proximity to the political powers of the time. This led to the production of tea ceremony utensils, which were in demand at the time, and to the mass production of general everyday items, which made Seto the center of the pottery industry in Japan. Therefore, to describe Seto ware in detail is to describe the history of ceramics and porcelain in Japan, but this section merely gives an outline of the general history of Seto ware and does not describe the technical aspects, such as clay, glaze, molding, decoration, kiln, and firing.

This section is only an overview, so please refer to the appendix at the end of this document for additional information. The three counties of Tsubogi, Kani, and Ena are adjacent to Seto and should be included in Seto ware from the standpoint of pottery industry and history.

Seto belongs to the former Higashikasugai County, but in the Heian period, it belonged to Yamada County and was later called Yamadasho Seto Village.

Later, Yamada-gun was abolished and divided into Kasukabe (or Harube) and Aichi counties, with the Seto area joining Kasukabe, which was renamed Kasugai-gun, and then in 1878 (Meiji 11), the area was further bisected into east and west, with Seto belonging to Higashi Kasugai-gun. Seto is located in the northeastern corner of Higashi-Kasugai County, about 20 km northeast of Nagoya City, and was incorporated as a town in 1892, merged with the neighboring Akazu Village and Aza Ima and Aza Minonoike, which were part of Asahi Village, in 1925, and became the only ceramic city in Japan when it was incorporated as a city in 1929. The geographical environment is composed of granite, granitic sandstone, sandy clay, clay, lignite, and gravel, or Tertiary New Formation (or Quaternary Pleistocene). In addition, the area was a very favorable place for pottery production due to the presence of black pines in the vicinity. Shinano Town is located to the northeast of Seto City, and was merged with Shimohonomura, Jyoshino Village, and Kakegawa Town in 1906, and was incorporated as a town in 1924, and was merged into Seto City in 1959. Mizuno Village is adjacent to the west side of Seto, and was the location of the Edo period (1603-1868) government office.

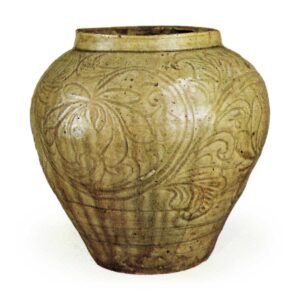

The origin of this practice is not known, but in the Nihon Koki (Nihon Koki), an article on the 5th day of the first month in the 6th year of the Konin Era (815), it is written, “Three people from Yamada County in Owari Province, including Sanke Jinbu Otomaro, have learned the art of zosai-shi. They are known as “Zosei,” and their origins are mentioned in the Engishiki. The “E-ke Jidai” states, “The inner table for the medicine is from the right side of the gate, and a hundred pieces of Owari toothpaste are served in celadon ware. The celadon in question is the five items given to the uchi-dzen from the shrine, as well as celadon from Owari. There is also a vermilion-lacquered vase. If you think about it, the celadon in the Engishiki is in fact the celadon mentioned in the Jiangke Jidai, and according to the same book, the “Goyaku” ceremony had already begun during the Kounin year (810-124), and thus the Goyaku ceremony (an event during the three days of the New Year to eat rice cakes, boar, deer, sweetfish, radish, melon, etc.; “goshugata” means “age” and “tooth” means “age”) is also said to have been held in this ceremony. It is thought that this ritual was also held around this time, and that the county of Yamada in Owari Province was ordered to produce celadon ware for this purpose, as described in the Nihon Kouki (Nihon Kouki). The Yamada County in Owari Province is mentioned in the Engishiki as having the “lid tsingko” (omitted below)” and “The area is clearly Seto and its vicinity, as well as the eastern part of today’s Aichi County, as indicated in the Yomei-chou. This has been proven by the excavation of the old kiln sites at the southwestern foot of Mt. There is no doubt that the three craftsmen mentioned in the Nihon Kouki (Nihon Kouki), including Sanke Nimbu Otoma, were from this area. These kilns, which had reached the height of their prosperity, were government-owned kilns and declined with the decline of the Imperial Court from the end of the Heian period until they finally lost their skills. In the Kamakura period (1185-1333), these kilns were restarted as private kilns, and at that time, they were collectively located in the Akazu area at the western foot of Sanage Mountain in the current Seto City area. At that time, pottery was produced in the Akazu area at the western foot of Mt. The above are mostly Seto-yaki drum-shaped water jars and pots produced by the end of the Kamakura period (1185-1333), all of which were of course made on the potter’s wheel.

However, the bottles and jars are wheel-thrown with the clay wheel and the bases are all attached to the potter’s wheel, and it appears that the wheel had not yet been cut out. What should be noted about early Seto porcelain is that the body of bottles and Buddhist vessels are decorated with plum blossoms, lotus flowers, chrysanthemums, nine stars, and nine-crested arabesques, while sword tips and single and double petals are stamped on the neck and hips, and the shapes and patterns are also heavily influenced by Chinese Tang and Song dynasty ceramics and Goryeo celadon. The shapes and patterns of these ceramics are also heavily influenced by Chinese Tang and Sung Dynasty ceramics and Goryeo celadon. In the early Muromachi period (1333-1573), or around the time of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, Seto’s pottery industry underwent a major transformation, and it began to shift from traditional religious utensils to miscellaneous daily-use vessels. In other words, the pottery of the previous period had almost completely disappeared from the Seto kiln, and there were no more Tenmoku bowls, Tenmoku-glazed small plates, incense burners, grandmother’s jars, etc., as well as large bowls (bowls), small plates, small bowls, large Buddhist vases, incense burners, Nigoridai, and underglaze dishes with ash glaze, and large and small deep plates, kataguchi, suribachi and water basins with orikomi or wave edges were also produced from the Kamakura period through the Muromachi period. These items were produced from the Kamakura period to the Muromachi period. The name “grandmother’s bosom jar” is derived from the name carved on a jar of the same shape and quality from the Azuchi-Momoyama period to the early Edo period (1603-1868), and these jars seem to have been produced in great numbers. There are also tenmoku glazed tea caddies excavated from these old kilns, but the number of these is extremely small. However, many tea containers and other tea utensils were excavated from the Heiko kilns, which are estimated to have opened after the Azuchi-Momoyama period, along with other miscellaneous vessels, but most of them seem to be ordinary or technical in form. Old kilns in the Seto region are generally located at the top of high mountains or on steep slopes. Later, silicate, a decomposed product of granite, was added to the ash glaze, and the glaze gradually became more complete, with a dark yellowish-green hue and blue and yellowish-brown tones in many cases. In the early stage of tenmoku glaze, the glaze is dark purple-brown with a blackish luster in the thicker areas. As time went by, both the glaze quality and form deteriorated, and by the Edo period, there were almost no pieces worthy of appreciation. It should be noted that most of the vessels of the same shape and quality as those listed above were produced in the mountains of central Toki County, Mino Province. However, there are only four or five kiln sites, and the glaze quality is somewhat inferior, suggesting that they were probably produced from the end of the Kamakura period to the end of the Muromachi period. A pair of Seto vases excavated from the precincts of Nagataki Hakusan Shrine in Nagataki, Gujo County, Gifu Prefecture, during railroad construction in 1933, have a black-blue, dependable glaze and are thought to date from the end of the Kamakura period. Nail-engraved characters on the body are as shown at left.

Hakusan Gongen Gohonin Gohonin Gohonin, Kiyohara Hiroshige, Aichi-gun, Oshu, December, 1st year of Shōwa era, Hakusan Gongen Gohozen, Nakajima-gun, Okuda Anrakuji abbot Ajari Eishu, December, 1st year of Shōwa era [Fujishiro era] The term “Fujishiro era” here is used to describe the period from Kato Fujishiro Kagesada I (Kamakura era) to his fourth generation, Fujishiro Masanobu (early Muromachi era), who created the tenmoku glaze and is said to be the founder of Seto pottery. (Kamakura period) to the fourth generation of Fujishiro Masaren (early Muromachi period), who is said to be the founder of Seto. The legend of Fujishiro has long been handed down, however, so here is a common theory: the tenmoku glaze was originated in Seto by Kato Shirouzaemon Kagemasa. Kato Shirozaemon, who was born in Seto, Japan, was a potter from his childhood (various theories differ as to his country of birth and other details) and traveled around the country to learn the art of pottery making. In March 1223, he followed the monk Dogen to Sung China, where he learned Chinese pottery techniques, and returned to Japan in 1228 (Anjeong 2), testing the clay of various countries but finding nothing to his liking. He settled again in Seto-eup, Yamada-gun, Owari, and found a good clay called grandmother’s bosom in Seto Satsu (Akazu-cho, Seto City), and finally built the Heiko Kiln in Satsu and fired Song-style Tenmoku-glazed vessels. In his later years, he shaved his head and took the name Shunkei, and died on March 19, 1249 (according to various theories), at the age of 82. His tea caddies are called koseto, those made from clay brought back from the Song dynasty are called toshiro karamono (or simply karamono), those made from Japanese clay and medicine are called koseto, and those made after he became known as Shunkei are called shunkei, etc. Works made before his return from the Song dynasty are called kuchite (thick-te), and tea pots made from clay from his grandmother’s bosom after his return from the Song dynasty are called grandmother bosom. The tea pots fired with clay from the grandmother’s bosom after returning from the Song dynasty are also called grandmother bosom. The karamono type is described as “earthenware of vermilion, purple, rat, and yellow with discoloration due to burning, with black and yellow medicinal candies, white medicine called snake scorpion, yellow medicine called bunrin yaku, with a reverse thread-cut board, all in one piece with a light finish”; the Kosedo type is “earthenware of white and yellow with fine thread cutting of black medicinal persimmon”; the Shunkei type “fired with Japanese and Chinese clay, with as yellow clay, medicinal persimmon, or yellow, with thread cutting in one piece. Shunkei is described as “a fine piece of work with a mixture of Japanese and Chinese clay. The types of Koseto tea containers made by Fujishiro I include: Atsute, Nenuki, Koseto, Ooseto, Koseto, Meimonote, Sembeite, Mushigui Fujishiro, Dai Shunkei, Natsuyama Shunkei, Hodeide, round jar, Bunrin, eggplant, Shiriage, Kuchibyouzu, Uchikai, Tebin, rice bucket, Suricha, Shigatzuke, Imoko, and Mimotzuke. The second generation, Fujishiro Motomichi (also called Fujijiro, Fujikuro, or Fujigoro), inherited the main family and lived in Satsu during the Bun’ei period (1264-75). Many of his products are Kizeto Hakuan-te, which are called Manaka-ko (sometimes simply Fujishiro, and Fujishiro Shunkei is added to Manaka-ko in the “Kiln Division of Tea Containers”) to distinguish them from Kozeto. The work is said to be “a piece by Fujishiro Ichigami 2nd generation, similar to Kosedo, similar to secondhand, earthen-root and yellowish-white, light red and black, some yellow, some blue, and with two colors of rings and threads,” while Fujishiro Shunkei is said to be “earthen-root and yellow, similar to threads and threads, like Shunkei, with a refined appearance, like Shunkei in body and ground medicine. The types include Hashi-hime-te, Noda-te, Oubite-te, Nezuto-Oubite-te, Go-Oubite-te, Ogawa-te, Shigawa-te, Mentori-te, Mentori-mentori-fudori-te, Imo-no-ko, Daikakuji-te, Yanagi-toshiro, Itome-toshiro, Hana-toshiro, Mushigui-toshiro, Grandmother, Duwaka-te, Shokumetori-te, Kamisoko-tode, candle-te, Koyaku-te, Go-yaku-te, Bodo-ko, Sasa-mimi, Hankiri, Iiboke, Oumi, Nasu, Sashi, Okuchi and Mizutomi. Fujishiro Shunkei includes Seto Shunkei, Nyonin te Shunkei, Tobi Shunkei, Tsubaki te Shunkei, Sogetsu Shunkei, and Yukishita Shunkei. Fujishiro Kagekuni III (also called Fujisaburo, Usashiro, or Tojiro) inherited the main family during the Einin period (1293-19) and lived in Satsu. Following the style of his great-grandfather Kagemasa, Kagekuni called his products “used” and went by the name Kinkazan. His work was called “Fujishiro III, clay, yellowish yellow, white medicine, persimmon black, yellow medicine is Fujinami’s, there are two colors of wheel and thread cutting, more elegant than the single Fujishiro, and there is a lot of gold and this is the most beautiful of the generations. The following are some examples. Fujishiro Masaren IV (also called Fujikuro or Fujisaburo) inherited the main family during the Kareki and Kenmu periods (1326-38) and made korogi, leaving the clay body in the shape of a gable and applying glaze, which was called a gable kiln. His work is said to be “Tozaburo IV, clay white and light red, medicine persimmon yellow or black, two colors of main thread cutting and ring thread cutting, all in one piece, and it is called Yakudome gafu ni kireru yu nametosu. There are also “tea caddy kiln parts” such as “tea caddy kiln parts”, “tea caddy kiln parts”, “tea caddy kiln parts”, and “tea caddy kiln parts”. The “Kiln Division of Tea Houses” continues with a section called “Goyo,” which lists the names of tea house artists from Rikyu (Azuchi-Momoyama period) to Enshu (early Edo period), including Joi’an, Shoyi, Shozan, Sohaku, Chausuya, Genjuro, Manyemon, Takean, Shinbei, Ezon, Yanosuke, Moemon, Kichihei, Junsai, and others. The above is a brief biography of Fujishiro IV and the description in the book “Kiln Portion of Seto-Saku Tea Containers,” but two questions naturally arise. One is a question about Fujishiro himself, and the other is a question about the “Kiln Portion of Tea Casks” itself, which is related to the above question. The other is the question of the “tea container portion of the kiln” itself, which is related to the question. The following are some of the points of doubt regarding Fujishiro that have been raised by various families: (a) The glazing method in Seto ware dates back to the Heian period (794-1192), far beyond the Kamakura period (1192-1333). According to the investigation of kiln sites, it seems that the ame glaze of the Kamakura period was developed and the ame glaze was completed in the early Muromachi period. (B) The Fujishiro period was a time when the winds of coffee brewing were gradually rising in Japan, but it had not yet become common, and was only used for medicinal purposes by some upper class people. (C) According to the legend of Fujishiro, when he returned from the Song dynasty, he brought with him the clay and glaze of the region, and after making an itinerant journey around the country, he came to Seto and made a type of tea container called “Fujishiro Karamono” with it. It is hard to believe that he would have carried such a large amount of materials during his long itinerant travels around the country. (D) If Fujishiro did indeed come to Japan, he should have first learned the most advanced techniques of the Song dynasty, such as celadon porcelain and Song red glaze, but it is suspicious that he learned only tenmoku glaze. (e) The Heiko kiln in Akazu, where Fujishiro is said to have built his first kiln after arriving at Seto, was not opened during the Kamakura period (1185-1333), but was built in the late Muromachi or Azuchi-Momoyama periods, according to the actual excavation of the kiln. Next, regarding the “tea caddy kiln portion” under Fujishiro, of course, there are many questions that can be considered in relation to the existence of Fujishiro. It is hard to imagine that there was such a large demand for tea containers during the Kamakura to early Muromachi periods. (b)

If the “tea caddy kiln division” is true, then the 200-odd years from Fujishiro IV’s Happu kiln to the post-kiln period would be a complete blank period, which would be extremely inconvenient. (C) It is difficult to believe that only four potters produced tea caddies in Seto in the old days. (D) When we consider the Seto Fujishiro genealogy, although the history of the first to fourth generations is clear, the history of the fifth to the twelfth generations is not clear at all, which is puzzling. The records from the 13th Soemon Harunaga (1566-, died in Eiroku 9) onward are based on relatively clear data, but the records from the first Fujishiro to the fourth generation of Hafugama are obscured by the “tea casserole kiln division” and other legends, which make the period look older, and the fifth to the twelfth generations are unclear, and it is doubtful that each generation really existed. In the end, the fifth to twelfth generations became ambiguous, and it is doubtful whether each generation really existed or not. The legend of Fujishiro is based on the “Bessho Kibei Issho Sho” written in the back of a book dated July 15, 1595, which has given rise to various popular theories. It is a very inaccurate folklore. In “Shinpen Seto Kiln Genealogy,” it is written that “Bessho Kibei’s ‘Issho Shohensho’ also says that Fujishiro I fired at the Heiko Kiln. According to the pottery shards and the kiln structure that have been excavated at the present Heiko kiln, it appears that the pottery was fired at the end of the Ashikaga period. In the preface to “Tōshi,” a translation of the Kibei version written by Rai Sanyō, it is written that Shiro of Seto began firing ceramics during the Ashikaga period. There are many references to the transfer of Akazu’s bottle kiln techniques to Mino’s Kusjiri. The same technique is used to produce pots with flecks of gold stream glaze over a black Kosedo glaze, which may be considered a precursor to Kusjiri tokkuri, as well as tenmoku tea bowls and small dishes. It is also possible that the Shino technique of the Asahi Kiln in Seto was transferred to Mino. Kage-no Kage of the Kusjirigama kiln received the name Asahi ware from Emperor Shojincho, perhaps because the scarlet color of the Shino glaze reminded him of the color of dawn, or perhaps because of his association with the Asahi kiln at Seto. The excavated pieces from both the Asahi Kiln in Seto and the Kusjiri Kiln in Mino tell this story, but is there any connection with the Asahi Junkei piece in the Bessho Kibei Ikko Shohensho (Bessho Kibei’s book of descendants)? The Asahi Kiln in Seto is said to be the site of the kiln of Fujishiro Kagemasa I, which “makes me think” that Fujishiro may have been a late Ashikaga. The “Taisho Meihiki Jiten” describes it as follows: “Now that I think about it foolishly, I think that kafu-kilns and the like were not made until after the Higashiyama period, and that they must have been made around the Koji period of the late Ashikaga Nobunaga’s reign. If we look at the age of the natural blast kiln, we can see that there were four generations from the original Fujishiro to Fujisaburo of the blast kiln, and that there are about 340 years between them. If we focus only on the quality of the tea container and do not consider the taste of the clay, it would be difficult to say that we are wise if we are wrong about the age (omission), He had been making Chinese ceramics of the Kosedo type for fifty years from the first year of Anjo to the tenth year of Bun’ei, and had ceased to do so for one hundred and seventy-eight years after the death of the original founder, and had established the Higashiyama-den tea ceremony since the time of Bun’ei, and was the first person to hold a tea ceremony in Japan. However, since we now call the pottery made by the second generation Fujishiro “Shinchuko”, it would be foolish to call the pottery made by the original Fujishiro “Shinchuko” after his death, and also his descendant Fujishiro “Fujishiro” after his death. The “Newly Compiled Seto Kiln Genealogical Record” states that Fujishiro was from the late Muromachi period, downgrading him from the Kamakura period, while the “Taisho Meikikan” states that “Fujishiro II was a potter of the late Muromachi period. The “Taisho Meikikan” dates the pottery from the end of the Muromachi Period or later, from the Manchuko-gama of Fujishiro II. The “Taisho Meikikan” theory is based on the question of why the only Seto tea caddy in the Daimyo-mono category is Tako Seto (by Fujishiro I), and why Shinchuko, Kinkasan, and Hafu kilns are in the Chukko-Meimono category but not in the Daimyo-mono category, which was also the theory of Kusama Waraku and others in the past. In any case, although Fujishiro is still ambiguous, he is the most important figure in the history of ceramics, especially in the field of tea ceremony ceramics, and it is said that the history of ceramics in Japan in the early period cannot be explained without him. Many more studies on Fujishiro will be needed in the future.

The Azuchi-Momoyama period: Ceramic technology in Japan, like handicrafts, was considered to have come from China and Korea, and until the Muromachi period (1333-1573), it was relatively infantile. Therefore, most of the ceramics used for tea ceremonies in the Muromachi period were imported Chinese ceramics, and domestic ceramics were not even considered. However, it can be inferred from a sentence in the “Yamakami Souji Ki” that the tea bowls of Nobunaga’s reign finally shifted to domestic ceramics, as shown in the following sentence: “In the present age, tea bowls are from Tang Dynasty to Koryo, Seto and Imayaki. The fact that the value of domestic ceramics was recognized in Nobunaga’s time is a sign of the cultural awareness of the tea ceremony masters of the time, but it also proves that Japanese ceramic technology itself had developed to a level that could be appreciated by the tea ceremony masters, who had the highest aesthetic sense at the time. In fact, this period was one of the most important periods in the development of ceramics in Japan, and the truth about the development and changes in techniques and designs after this period should all be traced back to this period. In particular, Seto ware was in the domain of Oda Nobunaga and was in constant contact with his political power and the tea masters, so it made the greatest leap forward during this period, surpassing all other ceramic production areas in Japan. Seto ware developed more kiln styles, techniques, and glaze types during this period, and its designs became richer and richer, and it stepped away from its previous imitation of China and Korea. In other words, the only glazes previously available were celadon-style ash glaze and Kosedo tenmoku glaze, but new types such as Setoguro and Oribe ware (the generic names for Shino ware and Oribe ware) were added. In addition, while the previous period had only employed extremely simple decorative techniques such as inka (seal flowers) and hana (flowers), in this period, for the first time, an ingenious invention was made to add vessel designs mainly using iron sand. In addition, feldspar was used for glaze, and new materials such as oniita and copper were discovered and used to color the patterns. In addition to wheel-thrown molding, he also invented the molding method from this period. The drawer-black technique, in which the potter uses an iron hook to pull the potter’s wheel out during firing, was also an original idea of this period. In contrast to the development of the kiln style, Seto had previously only underground burial kilns, but from the beginning of this period, these kilns finally appeared above ground, becoming the so-called semi-cellar kiln style, and from this time on, Kiseto with vitreous alumina, Shino ware, Setoguro, etc. were fired. The continuous climbing kiln style, which was introduced from Kyushu by Kato Shirozaemon Kage-nen, was further developed, and so-called Oribe ware was fired in this kiln. As the techniques became extremely complex and diverse, the variety of tableware, drinking vessels, decorative objects, and other items produced increased dramatically. Tea bowls, which used to be only tea caddies or tenmoku bowls for tea ceremonies, became popular as the Souan tea ceremony flourished, and other types of bowls were created such as Setoguro, Shino, and Oribe ware in addition to tenmoku type. In addition to tea bowls, bowls, plates, and mukozuke (a type of bowl with a small bowl) became more and more skillful with the development of Oribe ware, which made free use of patterns and forms, and their designs varied widely according to their uses, and almost all of the styles used today originated at this time. The prosperity of Seto ware during this period was truly spectacular, but the top of this period was the period of the highest quality products for tea ceremonies, which finally declined and retreated in the early Edo period. In general, the production of high-grade wares for tea ceremonies gradually shifted to Kyoto from the end of the Edo period, and Seto ware became exclusively a producer of miscellaneous daily wares.

Many pieces that are recognized as being in the early stage of the Nikiyo or Kenzan style have been excavated from kiln sites such as the Yashichida kiln in Kugari, Kani-cho, Kani-gun, Gifu Prefecture, part of the Ohira kiln, and the Otomi kiln in Izumi-cho, Toki-shi, Gifu Prefecture. This is the late stage of Oribe ware, meaning that the tradition of Oribe ware shifted to the Insei or Qianzan style in the late stage, and the style and technique were later completely transferred to the capital of Kyo Genbin, and the production of advanced ceramics for tea ceremonies disappeared from the Owari and Mino areas. The development of crafts progressed from simple to complex in response to the cultural demands of the time, and Seto ware was also stimulated by and demanded to produce extremely complex and varied ceramics in response to the developing trends from the reign of Nobunaga to the reign of Hideyoshi and the height of the tea ceremony, which was both before and after. The extreme complexity and variety of Oribe ware, for example, is not to mention its oddly shaped pieces, but it is also known for its elaborate techniques, such as joining a single piece of pottery with half white clay and half colored clay with high iron content, applying copper green glaze to the white clay, painting white mud on the colored clay, and applying iron sand patterns on top. This made it difficult to compete with the next completely new type of high quality wares, such as the color glazed wares of Kakiemon, Ninsei, and others, and it was forced to decline. Seto ware after the Edo period (1603-1867) was not engaged in the production of high quality products for a long time and mainly produced miscellaneous vessels with a beadlo glaze, which were called “Omamii-yaki” or “Genbin-yaki. It is important to remember that the prosperity of Seto during this period was due to the industrial policy of Nobunaga Oda and the artistic guidance of Oribe Furuta. The protection policy of Seto ceramic industry by Nobunaga can be seen in a letter of sanction given to Seto in December 1563 and a letter of red seal given to Ichizaemon Kato (Yosanbei Keimitsu) in the first lunar month of 1574. According to the above-mentioned letter and the red seal, Nobunaga adopted a very strong policy of protection and encouragement for Seto products, including freedom of trade and sales, protection of the market, exemption from new taxes, restrictions on attachment arising from loan-loan relationships, and prohibiting the opening of kilns elsewhere while limiting the management of the pottery industry to Seto. Of course, these were part of the industrial policy of Nobunaga, who was an economist, but it is also quite imaginable that Nobunaga, who was a tea master, specially considered Seto for the promotion of pottery. However, after the reign of Nobunaga, from Eiroku (1558-170) to Keicho (1596-1615), not a few Seto potters moved to Mino. The same is true of Yosanbei Kageshitsu and Genjuro Kagesunari, who moved to Kusiri, Toki-gun (Kusiri, Izumi-machi, Toki City), and Riemon Kagesada and Hitobei Kagesato, who moved to Gonoki, Toki-gun (Sogi, Toki City). This is the first time since 1567, when Nobunaga Nobunaga annexed Mino, which at first glance seems to indicate a decline in the Seto pottery industry, but the fact is that this was not the case. Originally, Seto and Mino were different countries, but they were bordering on each other, and the traffic of potters has been active since olden times. Therefore, the migration of potters was not a phenomenon that began during the reign of Nobunaga. At that time, with the invasion of Nobunaga’s strong political power, the Seto ceramic industry further expanded and the Seto ware blossomed like a million flowers in the Mino area. The prosperity of Mino ware was clearly founded at this time. In addition, Furuta Oribe is most closely related to Seto ware of this period. It is clear from the name “Oribe-yaki” that he always gave his own designs to his pottery, but what Oribe taught was not only so-called Oribe-yaki (including Shino ware), but he also gave his taste to tea containers from early on. The old tea ceremony books show that it was Oribe who originally created and taught the use of patterns on ceramics, so all Seto ware of the time, which had departed from the simplicity of the past and developed an extremely rich variety of forms and patterns, must have received direct instruction from Oribe. This is also confirmed by the fact that Oribe and Rikyu were recognized for their unrivaled aesthetic creativity at the time, and a survey of kiln sites in the Owari and Mino areas shows how closely Oribe ware correlated with Seto ware in general, which was produced at that time. The six Seto potteries said to have been selected by Nobunaga in 1563 and the ten Seto potteries said to have been selected by Oribe Furuta in 1585, both of which are now put aside for a moment to determine their authenticity, fully illustrate the great political and artistic influence and inspiration they had on the Seto pottery of the time. (There are other Oribe favorites, but Seto is the most direct one).

When Tokugawa Ieyasu came to power and his son Yoshinao (Prince Minamoto no Kei) was appointed to Owari, the brothers Kato Riemon Kagesada (Karasaburo) and Nihei Kagesato (Ko Nihei) were summoned from Gonokimura, Toki-gun, Mino (Sogi-cho, Toki City) on February 5, 1610, because it was unwise to dispatch the descendants of Seto ceramic founders to different regions. On May 5 of the same year, the brothers were summoned from Gonoki Village, Toki-gun, Mino Province (Sogi-cho, Toki City), and sent to live in Akazu to work at the imperial kiln. On May 5 of the same year, he summoned Shin’emon Kageshige from Mizukami Village, Ena County, Mino Province (Mizunami City, Toki Town, Mizunami City) to Shinano (1658-), and in the first year of Manji, Kagesada’s grandson Tahei Kagewa was also summoned to work at the imperial kiln. (Since then, Karasaburo Nibei and Taibei have been referred to as the three Goyamaya families in the world). In the Genna period (1615-124), he forbade the potter to take clay from his grandmother’s bosom without permission and gave him 200 ryo in gold and ordered him to use it to burn to the fullest, thereby encouraging his excellent work. During the Kan’ei period (1624-44), Yoshinao also built a kiln on the western side of Mt. Seto, northeast of the lotus pond in the outer wall of Nagoya Castle, and invited Nihei, Karasaburo, and Tahei to make pottery from the clay of his grandmother’s bosom. He called it Oniwa-yaki, and the public called it Onfukai-yaki. According to some sources, the person who moved to Kyoto in 1624 and started Awata-yaki was Sanjiya Kuemon, a potter from Seto. The development of the manufacture of daily utensils and their profit as an industry was mainly due to the protection policy of the Nagoya Domain. The clan lent money or wood to impoverished potters, and prohibited anyone other than descendants of the potter’s founder from operating the business without permission, making it a hereditary business for the family. At the beginning of the Kyoho Era, the system of one person per family was further established, and the second son or younger was not allowed to hold this position. The domain also exercised control over sales, and established the Seto Gozo Kaisho (storehouse office) to manage the business of buying and selling. For example, there were less than 100 kiln houses in 1804 (Kyowa 4), compared to 142 in 1773 (An’ei 2). It was the porcelain transmission method of Kato Tamikichi that restored Seto from this decline and made it once again the king of Japan’s ceramic production areas. Of course, as mentioned above, the new porcelain production was not solely the result of Tamikichi’s efforts, as it was required by the industrial and economic conditions of Seto. In other words, we cannot overlook the cooperation of the magistrate Tsugane Bunzaemon, who took pity on Kichizaemon and Tamikichi when they were forced to turn to agriculture due to restrictions on the ceramic industry during the reclamation of Atsuta Shinden (Atsuta Ward, Nagoya City) in 1801, and his son Tsugane Shoshichi Kato Karazaemon, who supervised the Nanjyo Dyeing Method, and others. Later, Karazaemon and others petitioned the feudal government to lift the system of exclusive occupation of the head of a household and allow the second son and younger to engage in the new porcelain business in Seto. In 1804, Tamikichi went to the Hizen region (Saga and Nagasaki prefectures) and spent four years painstakingly researching and finally introduced the new method of round kiln production. This was not only a period of major changes in manufacturing technology, but also a second revolution in the Seto ceramic industry, which marked the strong start of Seto ceramics as a modern industry. During the 14 years from 1807 to 1820, more than 90 households changed their main business to new production, and this momentum spread to the neighboring villages of Akazu and Shinano, as well as to other villages in Mino. In 1811, the clan sent Karazaemon to the neighboring village of Mikawa (Aichi Prefecture) and the nearby village of Kamishita-Handagawa to search for raw materials for porcelain making, and allowed him to establish a stone-powder water mill. In the following year, the Chikura Shiroishi used for new pottery production was initially mined in Nabeya-Ueno (Nabeya-Ueno-machi, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya City), but it was not good enough, so the company traded it for good quality products and salt from Hosono Village in Mikawa Province. During this period, master craftsmen such as Kawamoto Haisen-do gradually refined their techniques, and later there emerged good craftsmen such as Kato Gosuke. As for industrial improvements, Ichiemon Kato devised a shelving board and applied it to Seto kilns during the Tempo period (1830-1444). When products were exported to other countries, they were required to bear the wooden seal “Owari” to indicate that they were made in Owari by the account magistrate. The products were stored in the warehouse and controlled by the director of the main business and the director of dyeing, and the products were sent to the warehouse merchant in Nagoya, who was paid by the clan. The kuramoto merchants were also divided into two types: main business ware and dyed ware. The kuramoto was given a monopoly on the sale of ceramics and porcelain, and was responsible for paying a portion of the profits from Setomono to the domain, as well as for facilitating the potters by the order of the domain.

In addition, the clan entrusted Nagasaki magistrate of the Shogunate with the purchase of Chinese gosu for use in dyeing, except for Seto, and had Nagasaki merchants purchase Chinese gosu for the warehouse, which was then sold to Seto potters according to their demand, or lent to them on guarantee by the director of the warehouse. The stock of Setomono merchants was established in 1833 (Tempo 4), and other free trading was prohibited.

In 1842, when the system of unification of various stocks was abolished and free trading was permitted, the stock of setomono remained as a special exception, and in 1846 (Koka 3), the stock system was further tightened. In 1846 (Koka 3), the stock system was further tightened. The first overseas export was during the Ansei period (1854-60), when several hundred pieces of pottery were secretly manufactured for the U.S. market through an introduction by Mitsui & Co.

The amount of pottery produced during the Edo period is unknown, but a 1792 estimate puts the total at 20,000 ryo, 90% of which went to other territories. In 1819, the amount of profit from Setomono, including the amount of the “Tokinashi” (surplus), amounted to 200,000 ryo. This shows the great difference in development before and after the production of porcelain. The Seto ceramic industry had to leave the protection of the feudal government for a long time after the Meiji Restoration, but the industry was given the opportunity to operate freely and the business was flourishing year after year. The value of Seto ceramics became even more prominent overseas after the 1872 Austrian Exposition and the 1878 Paris World Exposition. In 1868, Shigeju Kato changed the number of fire holes in the front section of small kilns from one to three to improve the distribution of fire and reduce kiln failures, In 1875, Tomotaro Kato and Tomitaro Kawamoto introduced the plaster mold process to Gosuke Kato and Masukichi Kawamoto. Inoue Nobutoshi was the first to produce products for export to China in 1885, and Kato Matsutaro invented a half-finished porcelain product called “Shinzan”. In the commercial field, a man named Takito Manjiro established a Setomono trading company in the area in 1871, opened a branch in Tokyo in 1874, and moved it to Yokohama in 1881 to facilitate foreign trade. In 1883, a new reference exhibition hall was built, and in 1895, the town pottery school was established. The outbreak of World War I in July 1914 caused a temporary depression, but the war eventually opened the world market to the major ceramic-producing countries, and the production and export of Japanese ceramics made a remarkable leap forward.

By the way, what is the production situation of Seto after World War II? The production value in the 1965’s shows a dramatic increase (according to the “Seto Area Ceramic Production Status Chart” by Aichi Ceramic Industry Association).

Of the total production value in 1971, domestic sales and export sales are as follows.

As can be seen from the above sales figures, export sales accounted for nearly 55% of Seto’s total production value. Moreover, toys and figurines accounted for 64% of the total export value, followed by Western-style food and drink utensils (26.8 %) and tiles (5 %). (Around the Muromachi period (1333-1573), the celadon ware of the Heian period was combined with black stoneware of the Kamakura period (1192-1333), but around the Muromachi period (1333-1573), the celadon ware changed to yellow Seto, and new types such as Shino and Oribe were added, and iron or copper glazes were used, and the base gradually became hard and white in color. Finally, in the early Edo period (1603-1867), the application of underglaze blue flowers, probably by a naturalized Japanese artist, came to be seen, and this was the origin of Nankyozuke, but the quality of the wares was still very much in the interim before the so-called “new porcelain” was produced. After black-glazed tea utensils, water jars were produced with persimmon-colored glazes, and some progress was also made in so-called “main business” ware. However, there are no widely accepted theories about the production techniques used in the early Edo period. In 1770, Kawamoto Jihei I produced sea squirt pots at a new kiln on Sutra Mountain and presented them to the Owari family, which had long neglected them. For his efforts, he was granted permission to leave the area. Jihei also learned the glaze techniques of persimmon, black, kizeto, unokara, and other styles from Gen’emon, a good craftsman of the time. After 1789-1801, in the main business section, Takeemon began to produce large sunkoroku. In the main business section, Takeemon produced large Sunkoroku, Shunkei Shibushi, Annan, Sung Guroku, Oribe, Shino, and Kizeto glazes; Juemon produced Unokara, Akaraku, Akashino, lapis lazuli, Seto celadon, and Ueno glaze large ware; Shin Goemon produced lead color, Takatori, Kin Nagashi, and Akaraku; Chobei produced Ishihaze; Jikichi produced Koshu, Itome, Itomoku, Embroidery clay, Roshu, and Mokunami; Hanemon produced Kakegoshi, Persimmon, Black, White, and Kanshitsu large ware; and Hanemon produced Kakegoshi, Kaki, Kaki-shi, and Mokuninami. Hanemon produced large wares of kakegoshi, persimmon, black, white, and kan-iri, Heizaburo produced higaki, and Kiheiji produced celadon porcelain. Doroshima porcelain produced hagi tea bowls, large white wares, red bowls, and sand bowls. In the Sometsuke category, Tamikichi was an Imari-style thinware maker at the Maru kiln, Jihei was a master of the Shintate style at the Fujishiro kiln, Kanroku was a craftsman of beast heads, etc., Karazaemon fired large wares at the Maru kiln, and Chuji was good at square wares such as Kumiju. In 1819, Gosuke shifted to celadon porcelain and produced kumibai cups by refining the raw materials, and he also devised celadon glaze for small dishes. He also devised celadon glaze to produce small dishes, which are now known as “small plates with a ball border. In 1822, Sadazo of Shimohinono produced Korai handmade porcelain, and Gosuke II finally produced fine celadon porcelain. It was called Kanroku celadon. Akatsu no Haru was a master potter of the early modern period who worked at the Omamai Kiln for the feudal lord Yoshikatsu from 1850 (Kaei 3). Gosuke IV succeeded to the family in 1863, and took pains to improve the designs and patterns, creating white porcelain and celadon porcelain with white heaping patterns. In 1879 (Meiji 12), Kato Matsutaro produced what he called “hanzuke” (half-glazed porcelain), which was made by applying a top-coat of porcelain clay on a ceramic base. This was called Shinzusuke. The above is a description of the increase in glaze types and the discovery of new methods since the mid-19th century in relation to each potter, and in the following half period, he competed exclusively in celadon, white porcelain, lapis lazuli, and other techniques, finally producing copperplate blue-glaze and brocade. The first product at the time of the establishment of porcelain was tea bowls, the first of which was a deep bowl for the first tea ceremony.

The first products were deep-dashi for Bancha, and the first patterns were engraved, that is, engraved on the porcelain base and then dampened with painted glaze, in the style of Kowari and Chowari.

The first form of the teacups and rice bowls was the warped teacup, followed by the round teacup, then the Kumagaya teacup, and finally in 1871 (Meiji 4), the Hiranara teacup came into fashion.

The number of old kilns in Seto varies according to various books. For the sake of convenience, we list the names of old kilns in “Wahari no Hana”, but the number of old kilns is not limited to those listed here. The old Seto cellar kilns are highly mobile, as already mentioned, and there are hundreds of kiln sites in addition to those listed above. Names of Old Seto Kilns” Heiko Kiln, Grandmother’s Kai Kiln, Asahi Kiln, Sunset Kiln, Tsubaki Kiln, Takatsuka Kiln, Takahara Kiln, Zenchoan Kiln, Genji Kiln, Kaniko Kiln, Koseto Kiln, Takatsuka Kiln, Mehoso Kiln, Ohkedo Kiln, Umagashiro Kiln, Yotsuji Kiln, Tsutagaru Kiln, Zenabe Kiln, Sannugado Kiln, Hari Kiln, Yamawaki Kiln, Nekoda Kiln, Nanga Doro Kiln, Nagata Kiln, Doyama Kiln, Furin Kiln, Yasude Kiln, Insho Kiln, Ji Kiln, Hosokura Kiln Hosokura Kiln, Shiraji Kiln, Mineide Kiln, and Takaba Kiln. Names of Akatsu Kogama” Hira Kiln, Konagazogama, Fujisaka Kiln, Oodoro Kiln, Goyo Kiln, Mitsu Kiln, Kurosan Kiln, Yokomine Kiln, Soyogihei Kiln, Hachimantaira Kiln, Makimine Kiln, Scallop Kiln, Aki Kiln, Yamanaka Kiln, Shimenki Kiln, Uchikura Kiln, Nagazogama, Nashikizawa Kiln, Kawahira Kiln, Shinsa Kiln, Torimine Kiln, Odorihei Kiln, Kasamatsu Kiln, Jorye Kiln, Takahashi Kiln, Kanzakihei Kiln, Kodamaishi Kiln, Hachi-gama, Hikari Kiln Kiln, Taki Kiln, Nagamane Kiln, Nandong Kiln, Yamakuwa Kiln, Shobu Kiln, Shirane Kiln, Kanda Kiln, and Kure Kiln. The following is an outline of the periods and types of pottery excavated from the major Seto kilns: (1) Asahi Kiln, late Muromachi Period, white tenmoku, small yellow Seto dish, camellia-shaped dish, tea caddy, early Shino ware, etc. (2) Kirihata Kiln, early Shino ware, etc. (2) Kirihata Kiln, Shino, Oribe, iron painting on brushed white lacquer, kaki-otoshi, or dropped gallows, etc. (3) Kikuhata Kiln, late Muromachi period, Kozeto: tea pots, tea caddies, Buddhist vessels, water droppers, etc. (4) Tsubakigama Kiln: Centered on this Tsubakigama kiln, there are groups of old kilns such as Magajo, Ohashi Genji, Matsudome, and Kayahara, dating from before the Kamakura period to the Muromachi period. The most frequently excavated items are Koseto celadon ware, including a blue celadon cup with a marigold cup, a jar with an inka flower, a potter’s wheel, a bottle, a water dropper, a tea container, a tea bowl in the style of Gyoki ware with a fragment of a guardian dog, and a tea bowl in the style of Gyoki ware, commonly called tsubaki tenmoku. (V) Koseto-glazed tea caddy, Koseto-glazed tea caddy, Koseto tenmoku, sealed vase, small dish, early E-Seto ware, etc., from the same period as the Asahi-gama, Koseto ware. (6) Contemporaneous with Detsubaki-gama. (VII) Contemporaneous with the Hundred Days Kiln; jar with sealed flowers, incense burner, etc.