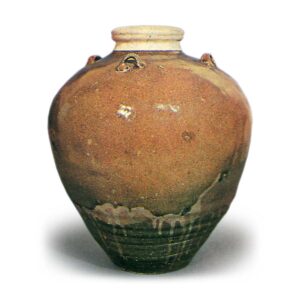

In a very broad sense, chatsubo is used to refer to a pot used to hold tea. A tea urn used to hold leaf tea is called a chatsubo (tea urn), while a tea urn used to hold leaf tea is called a chatsubo (tea pot). The word “mazubo” probably means a true pot. Because it is a ceramic pot used to hold leaf tea, it is larger than a tea jar used to hold powdered tea. In the old days, the jars were hung by nets made of dream or litchi, but after Shukoh, net bags of reddish-purple thread became popular, and they were sometimes decorated with gold brocade lidcovers. According to the “Kundai Kangenjochoki,” leaf tea pots were not used for decoration, even if they were valuable. During the Edo period (1603-1867), tea pots filled with tea for the shogun traveled back and forth between Uji and Edo, and the journey was quite a thrilling one. Tea pots were generally made of Chinese porcelain, but some were made in the Lu-Song period, and since the Edo period, Shigaraki-ware and Tanba-ware have become famous. Tea urns used to be a highly prized item, but today they are almost entirely abandoned by tea masters because they are too large to be displayed and because there is no longer a need to store leaf tea in each household. It is said that in the old days, those who did not have a tea urn did not hold a kuchikiri tea ceremony. The three main types of tea pots used by the Senke were Ro-Song, Seto, and Shigaraki, with the Ro-Song being the best. During the reign of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598), the popularity of true jars led to a shortage of tea jars, and the Sakai barn owner Sukezaemon was ordered to go to Ro-Sung and bring back a large number of jars, which Rikyu then selected and distributed to the lords.

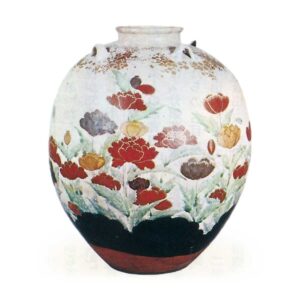

According to “Montanus Japan”, Hideyoshi pretended to ignore the business of the monks dispatched by the Lu Sung because of the large revenue from the Lu Sung, as well as the availability of true pots and other rare items. When Hideyoshi heard about this, he had them arrested and confiscated all the jars they had collected, forbidding them to bring them back to Japan in the future, and strictly ordering them to be put to death if they broke this prohibition. Among the top examples of true jars of the Lu and Song dynasties are those called lotus flower wang and ching xiang. The former has a lotus flower on the shoulder with the character for king, and the latter has the character for qingxiang. The most famous mahoutsukas of the Tensho period (1573-192) include Mikazuki, Matsushima, Yaezakura, Shijuseki, and Matsuhana. Crescent Moon is said to be one of the most famous jars in the world. It was named after the seven large bumps on the front of the jar, which were slightly tilted to resemble a crescent moon. It is said that the Matsushima pot also had more than 30 masses, and the scenery was so interesting that it was named after a scenic spot with a large number of islands. The Yaezakura jar perished in Sakamoto, Omi Province (Shiga Prefecture), together with Mitsuharu Akechi Samasuke. The 40-koku jar belonged to Ashikaga Yoshimasa and was considered the best jar in Japan after the above three items were lost, and was in the possession of Hideyoshi along with the Matsuhana. The flower originally belonged to Zhuguang, and was Huangqingxiang by Lu Song. The tea urn is described in the “Kimidai Kangenjochoki” as a “treasured item from the old days, and even though it was the property of the nobility, it is not found in the Mikasaeri. In the Yamakami Souji Ki, written in 1588 (Tensho 16), the names of crescent moon, Matsushima, Shijuseki, Matsuhana, Suteko, Nadeko, Sawahime, Kisakata, Tokika, Hyogo pot, Yaho pot, Hashidate, Kuje Yaezakura, Torashin, Hakuun, Susono, Sogetsu, Shigure, Jorin pot, Chigusa, and Miyayama are listed, and their tastes and points of appreciation and where they came from are described in detail. The article also describes the high value of the crescent moon and other items, noting that “Miyoshi Roshi pledged 3,000 kan to Taishiya, then gave the tea jar to Lord Nobunaga at Taishiya, which was decorated with poppy design in colors by Ninsei. In “Kitano Taichayu no Ki,” Hideyoshi boasted about his tea pots, which included 40 koku, Shiga, Natsuko, Suteko, and Shoka. However, the gradual decline of the tea urn from the viewpoints of tea masters is illustrated in the article “Classified Grass and People’s Wood,” which states, “Once upon a time, the deceased had their own names for their utensils: one tea urn, two kettles, three tea containers, and four characters. ・・・・・ The names of the middle period were one tea urn, two hanging items, three kettles, and four tea containers…” (The tea pots of the present period include one tea container, two tea containers, three tea containers, and four tea containers…) The name of the tea ceremony in the mid-19th century was “i-cha-iri, ni-kakemono, san-hanasei, shi-kama, shi-chatsubo no sata” (no tea pot sata in this generation). Even so, tea pots have traditionally been valued, and Kobori Enshu’s “Ganmon Meimono Ki” records that there were 18 types of tea pots owned by the Tokugawa shoguns and 73 types owned by lords and princes.

The Tokugawa Shogunate seems to have begun ordering tea from Uji in Yamashiro Province (Uji City, Kyoto Prefecture) during the Keicho period (1596-1615), and the passage of tea was modest, but from 1632 (Kan’ei 9), during the reign of Shogun Iemitsu, the eligibility for tea pot passage was made equal to that of the regent imperial family gateways, and even lords were required to avoid the passage of tea pots when they encountered them. When they met, they were required to avoid the road, while the attendants were required to dismount and the laymen were required to get down on their knees to be escorted to and from the tea ceremony. The tea ceremony was conducted by a tea ceremony head and two priests, and the clique head guarded the road with a group of old men. The head of the tea ceremony, accompanied by a group of old men, guarded the road and brought many famous tea pots with him to Uji, where the tea was stored for about 100 days on Mt. At the stations along the way, the tea was served by the shogunate’s local government, while the lords of the lords’ territories were hospitable and the passage through their territory was extremely quiet. Since the reign of Ietsuna, tea pots were no longer kept at Atago-yama, but at Kai-no-Tani-mura (Tsuru City, Yamanashi Prefecture), and all escorters would return to Edo once and return there in the fall to bring them back. However, during the reign of Yoshimune, this system was reformed in consideration of the cost of station roads and the hardships of the workers. In 1738, the convoys were no longer kept in Tanimura, but were sent immediately from Kyoto to Edo and stored in the Fujimi Tower in Chiyoda Castle. In 1809, during the reign of Ienari, the practice was restored to its former glory, but with the uproar at home and abroad at the end of the Edo period, this practice was also carried out in secret.