Chawan (tea bowl) was originally named for serving tea, but later came to refer to a wide range of ceramics and porcelain, and only to eating and drinking vessels in the Middle Ages. The term “chakeng” in the Heian period (794-1185) seems to have referred exclusively to glazed stoneware. At that time, there was a vogue for tea ceremony, which was a Chinese custom, but it was more for medicinal purposes, prized for its stimulant effect and practiced among the nobility. Because of this, the name chakeng (茶坑) was coined, and it eventually became a common name for stoneware quality. The word “chakeng” was also used to refer to the stone burning process. In the Kasuga Matsuri article of the “E-ke Yochi”, it is written, “Naka-Kanpaku, a messenger, went to Kanetoki’s house in Yamazaki to drink water. Kanetoki, without earthenware, offered a cup of tea. Kanetoki was doubtful. Kanetoki, having obtained the intention, offered the tea bowl and handed it over to the person in front of him. The tea is glazed stoneware. In addition, the “Shoku-kojidan” (Continuing Ancient Matters) says, “The tea ceremony is said to have been served during the regency of Fujiwara no Kaneie. In the “Yamato Monogatari”, “Yoshimine no Munesada no Shoshogun (omission), the tea ceremony is said to have been conducted in a tea urn with the bones of the deceased” in an article from the 9th year of Chougen (1036) of the “Ruju Zojyo”. The Azuma Kagami, October 20, 1185, article, “Tea bowls and tea utensils: 20 words,” etc. The Azuma Kagami, October 20, 1185, says, “There are 20 articles on tea utensils. These texts from the Heian and Kamakura periods both refer to tea bowls as a generic term for ceramics. The late Muromachi period’s “Kimidai kanjyochouki” (The Record of the Right and Wrong of Kimidai) mentions tea bowls under the title “tea and tea utensils. The “Kundai Kanjo Choki” of the late Muromachi period (1336-1573) lists celadon, white porcelain, and raoju under the title “tea and tea utensils,” and tenmoku under the title “clay and clay utensils. This is a distinction between porcelain and ceramics. The term “chawan-no-kuhin” is also found in “Sendensho. In modern times, chawan-ya meant porcelain stores. (The Korean tea bowls that were actively imported after the late Muromachi period (1333-1573) were especially prized in the chanoyu (tea ceremony), as described below. ) The reason why rice bowls are called “chazuke-bowl” or “iicha-bowl” is to distinguish them from lacquer bowls, a custom that probably began in the Edo period (1603-1867), when Imariyaki and other stone ware became popular. According to the “Morisada Manuscript” of the end of the Edo period (1603-1867), “The tea drinking bowl is of course called a tea bowl, but now a porcelain rice bowl is called a tea bowl, and a tea bowl for tea is called a tea bowl for tea, and a chazuke-chawan for rice. The tea bowls up to the Bunka period were the morning glory-shaped tea bowls with a diameter of 2″ 67″ and the tubular tea bowls of the same diameter, the tubular tea bowls being for the lower classes, and the small tubular, round-backed tea bowls with a diameter of 2″ 12” being used exclusively in all three cities since the Bunka period. There is also a large, thicker, taller, and more densely painted tea bowl of this shape, called a yuyu, which is not a tea cup, but is used exclusively for one’s own tea and not for guests at tea fairs. The current vendors classify rice bowls according to shape, with the larger ones being called moryo or molyu. Teacups include bell-shaped teacups (similar to a Buddhist bell), bancha drinking cups, anti-shaped sencha teacups, kakukoshi, marukoshi, and hata-ban.

Rinari [tea bowls for chanoyu] There are three types of tea bowls used in the tea ceremony: Chinese, Korean, and Japanese, with Korean ones being the most prized. Many Chinese bowls were originally created as tea bowls, while some Korean bowls were converted into tea bowls by converting rice bowls, brush washers, incense burners, kataguchi, vinegars, soy sauce containers, and the like into tea bowls.

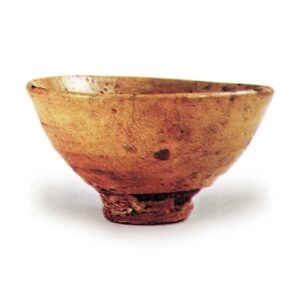

The larger ones are used for dark tea bowls and the smaller ones for light tea bowls. There are also summer and winter tea bowls. The name comes from the fact that shallow, flat bowls are used in summer and deep, concave bowls are used in winter. There are also five types of tea bowls, namely, Tsutsu, Iibitsu, Shioge, Kataguchi, and Tobiguchi. They are named according to their shapes. The following types are widely used and respected in the tea ceremony. Chinese wares include tenmoku, celadon, and somezuke. Tenmoku is the main type, and there are several types such as yohhen oil drip, leather cup, gray-colored cup, and jianjian cup. Celadon porcelain is mainly made of doll’s hands, and there are several types of underglaze blue ware, such as Undo and Wuzhou. Korean teacups include Idokomogaito and Taihisan ikatsugi Mishima, Kumagawa, Hakeme, Tamagote, Wari Takadai, Kinkai, Gohonshomaru, Kate, Ameleki, Gohon, Kumotsuru, Kyogen Hakama, Kaki no Uke, Kureki, Uoya, Kobiki, White, Soba, Iraho, and others. There are also more detailed types according to various characteristics. Among Japanese ceramics, Raku ware is the most appreciated, and the works of Chojiro I, Nonko III, and Honami Koetsu are especially prized. Seto ware includes Hakuan, Tenmoku, Shino, and Oribe. Kuniyaki include Karatsu, Shigaraki, Satsuma, Asahi, Iga, Hagi, Izumo, and others such as Shozui, Motobu, and Ninsei. Unlike tea containers, there are no sources for tea bowls, and those listed in “Gankan Meimono Ki” are considered to be the greatest masterpieces. The “Tea Ceremony Meimono Koe” is a collection of tea bowls and tea ceremony utensils. The “Chado Meimono Koh” defines all items in the “Taisho Meikikan” as meimono. There is a saying among tea masters from ancient times, “Ichiido Niraku San Karatsu,” and “Ichiraku Nihagi San Karatsu,” which indicates the tastes of tea masters. Korean tea bowls are the most respected, with Ido being considered the king of tea bowls. Chinese tea bowls are not appreciated except for tea ceremonies, and are rarely used in the tea ceremony. Chosun wares were originally daily utensils made by unknown potters in Korea, but tea masters in Japan recognized in them a taste for the wabi and sabi, and only in Japan were they especially praised, which must have been a surprise to the potters who made them. Only Japanese Raku ware was made for the tea ceremony from the very beginning, and every preparation was made to savor the taste of tea. In recent years, the taste for tea bowls has gradually changed, and Shino, Shigaraki, Ninsei, etc. have come to be respected more significantly than in the past. Please refer to each section for more information on each type of tea bowl. There is a common saying that a tea bowl is a highlight or a promise. In the case of Ido, it refers to the Takadai, Kairagi, Kuchi-zukuri, Chamadori, Chasen-zure, Koshi-zukuri, etc. In Hakure, there are ten oaths and twelve articles. In the case of Raku tea bowls, Kuchizukuri, Chamadori, Takadazukuri, Takadai Wakitakuri, and Mae are called the five highlights of Raku tea bowls. However, there are some differences depending on the style. In the sencha ceremony, small white porcelain bowls from the Ming dynasty of China are prized. The reason for this is that it is easy to see the bluish-yellow color of the tea. The shapes of these two terms, “cup” and “stong,” have only slight differences. Sencha bowls are now used daily. Incidentally, it was not until the end of the Meiji period (1868-1912) that the flat, round-bottomed teacups for daily use began to be covered with lids.