Shigaraki also has a long history. Like other medieval kilns, from the Kofun to Heian periods, Sue ware and ceramics in the same vein were fired in anagama kilns.

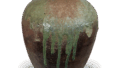

From the Kamakura to Muromachi periods, jars, pots, and mortar were fired, but Shigaraki jars from the Muromachi period are particularly attractive compared to those made at other kilns that fired pottery. This is because the clay is low in iron and the skin is slightly reddish in color, making Shigaraki jars the most highly valued among medieval pots among potters today. It was also used early in the tea ceremony, as Murata Juko (1423-1502) used the term “shikarakimono” in a letter to Furuichi Harima, and its name is mentioned in the “Chagu-biu-shu” of 1554, along with Bizen. In addition, the “Katsuragawa Jizo Ki,” copied in 1558, mentions the use of Shigaraki jars for coarse tea leaves, along with Bizen and Seto jars. Later, small jars and ramie tubs that caught the eye of Takeno Shao’o Take no Jo’o (1502-55) were used as water jars, and it is assumed that the production of tea ceramics to order also began. In the Tensho period (1615-1626), Shigaraki potters produced water jars to the taste of Sen no Rikyu, and in the Keicho period (1615-1668), they produced a series of water jars and tea bowls to the taste of Oribe, who dominated the period, as well as pieces to the taste of Kobori Enshu and Sen Sodan. In addition to Shigaraki ware, the Kyoto kilns also began to produce what were known as nisei-shigaraki and haka-no-shigaraki ware.

Shigaraki ware was apparently fired in Kise, Maki (Maki), and Tesho in Kumoi Village, Koga County, as well as in Nagano and Kamiyama in Shigaraki Town. From Nagano in Shigaraki Town to the north, black-skinned ware was fired using clay with high iron content until the Momoyama Period, while white-skinned ware, unique to Shigaraki, was produced in the south. In particular, the Goinoki kiln on the border with Iga produced beautiful ash-glazed ware. The Kizan and Marubashira kilns in the Iga territory are also thought to have produced wares in the late Muromachi period that were difficult to distinguish from Shigaraki wares. Therefore, the general opinion is that it is difficult to distinguish between Shigaraki and Iga wares made before the early Momoyama period. However, once Shigaraki began to produce pure tea ceramics, a major difference in style between Shigaraki and Iga began to emerge. Iga ceramics were thoroughly hardened, often thickly ash-glazed, and most of the vessel forms were strongly individualistic, based on Oribe’s taste, while Shigaraki ceramics were based on the Shigaraki of Shao’o and Rikyu, and the style was generally more gentle.

The most interesting Shigaraki of the Keicho period is a series of works called Korai Shinbei Shigaraki, which includes a water jar excavated from the site of the Arirai Shinbei residence in Kyoto.

In addition to Shinbei, there was another master potter in Shigaraki named Shinjiro, who is said to have carved the character “new” on his works.

In the “Tea Ceremony Essentials,” Volume IV, “Chadoh zenkai,” there is an inscription that reads, “The best Shigaraki work is Shinjiro’s, with a title of ‘Shin’ character, but the ‘Shin’ character looks like an ‘ori’ (fold),” which is true. Shinbei Arirai was originally an influential merchant who ran a “itowari-bushi” business, so it is thought that he was related to Shigaraki ware more as a merchant or a sukiya than as a potter, but Shinjiro may also have been a potter.

An overview of Shigaraki pottery styles from the late Muromachi to the early Edo period reveals that Shigaraki pottery was generally gentle in style, and tea ceramics did not have strong personalities. In the Edo period (1603-1867), Shigaraki ceramics also began to produce glazed ceramics, most notably “Shigaraki Koshihaku Tea Jar,” similar to Seto, which was presented to the Shogunate and feudal lords.

In the Edo period, the terms “Shao-o Shigaraki” and “Rikyu Shigaraki” were used to refer to a single style of pottery, but they are thought to have originally referred to water jars owned by Shao-o and Rikyu, and Enshu Shigaraki refers to Enshu Kirigata ware, while Sotan Shigaraki seems to have been a general term for all Crying Bimono ware from the early Edo period.

As mentioned above, among the kilns that fired pottery during the Middle Ages, none has left behind as many excellent jars as Shigaraki. The main products of all kilns were jars and mortars. Bizen, Tanba, Echizen, and Tokoname all have a high iron content in their clay, resulting in a blackened finish, whereas Shigaraki has a white clay with low iron content, which turns red during firing and produces a bright and peaceful scene of elegant pottery that is unparalleled in other kilns. Such beauty is still very attractive even today.

In the late Muromachi period (1336-1573), tea masters used Shigaraki jars and mortar bowls as vessels for the tea ceremony, and a Shigaraki water jar can be seen in a tea ceremony diary from the Tenmon period (1573-1584). Some of them may have already been made as mizusashi, but it is thought that most of them were jars or oni-otsuke, which originated as miscellaneous vessels. Later, tea ceramics based on the style of such miscellaneous vessels were fired, giving rise to Rikyu Shigaraki, a simple style favored by Rikyu, and in the Keicho period, Shinbei Shigaraki and Oribe-style ceramics were also produced.

In the Edo period (1603-1867), the style of Shigaraki ware changed, as seen in the words “Enshu Shigaraki” and “Sotan Shigaraki. Of course, miscellaneous jars were also made, but the characteristics of the period are strongly expressed in pottery made for tea ceremonies. It is widely known that during the Edo period (1603-1867), leaf tea kilns were fired as a specialty.

Many of the flower vases are not as good as those made in Bizen or Iga. However, one of Shigaraki’s most prized items since ancient times has been stone wash baskets. Some of the stone wash basins that have survived date from the late Muromachi period, but many were made from the Momoyama to the early Edo period. The traveling pillow-shaped flower vase is also common in Shigaraki, and is one of the most typical Shigaraki works. Tea bowls and tea containers have also been produced since around the Keicho period, and it is estimated that they were produced well into the early Edo period. However, the actual situation is not clear.

Shigaraki Ware

Explanation

Explanation