There are still many things about the history of Japanese ceramics before the middle of the Edo period that are still unknown. This is not surprising, of course, as there are few reliable written records or works that tell us about kilns and potters, but among these, there are relatively many records about the Kyoto-yaki potters Ninsei and Kenzan. There are far more reliable records of their kilns and works than there are of local kilns and potters over the period of about 100 years from the start of the Omuro ware, when Ninshō was active, to Kenzan’s death in Edo. This is because Kyoto was the city that was most positive about recognizing individuality in the Edo period, and because they were able to associate with the leading figures of the time. In the case of Kenzan, it was due to the fact that he was born into the prominent merchant family of Karakin-ya in Kyoto, and also because he himself left behind many works of high documentary value, in particular the book on pottery-making, “Toko Hitsu-yo”. In the case of NINSEI, many articles were recorded in the diary of the high-ranking Kyoto intellectual of the time, the abbot of Rokuon-ji, Hōrin Shōshō, called “Kakuhōki” (The Diary of Kakuhō), the diary of the abbot of Sōjū-in, Kenshō, called “Ichi-onbō Nikki” (The Diary of Ichi-onbō), and the diary of the high-ranking Kyoto intellectual of the time, the abbot of Rokuon-ji, Hōrin Shōshō, called “Kakuhōki” (The Diary of Kakuhō), the diary of the abbot of Sōjū-in, Kenshō, called “Ichi-onbō Nikki” (The Diary of Ichi-onbō), and the diary of the high-ranking Kyoto intellectual of the time, the abbot of Rokuon-ji, Hōrin Ichijōshujin Hina-mi-ki, the diary of the monk Kiyohito, and Ichijōshujin Hizokki, the diary of the monk Kiyohito, and so on, and his works were admired by the aristocracy, especially the court nobles. This is because Nisen’s works themselves were far more refined and superior to those of other Kyoto kilns, and even looking at the works that still exist today, Nisen’s position in Kyoto-yaki pottery before the middle of the Edo period is outstanding. In the history of Japanese pottery in the Edo period, not only in the world of Kyoto-yaki, there is no one other than Nisen who added the elegant pottery described by the word “glossy”.

The kiln of Omuro Ninshō was located in front of the gate of Ninna-ji Temple in Rakusai. The exact date of its founding is unknown, but after the Onin War, the famous temple of Ninna-ji, which had fallen into disrepair, was rebuilt by order of Tokugawa Iemitsu, with Kinoshita Awaji-no-kami and Aoki Kai-no-kami as construction supervisors. it is thought that the opening of the Omuro kilns in front of the temple must have been after that, in October 1646, when the chief priest, Prince Kakushin, the first son of Emperor Goyo, moved from his temporary palace to the new palace. Furthermore, in the “Kakunin-ki” (a book that often describes early Kyoto-yaki, such as Kyoto-yaki, Awataguchi-yaki, and Yasaka-yaki, etc., since its first appearance in 1639), it is written that “Kamonoseki-no-kami came, and Omuro-yaki tea caddy was given as a gift”, and it is thought that Omuro-yaki was first mentioned on January 9th, 1648. Matsuya Hisashige of Nara, who was invited to a tea ceremony held by Kanamori Sowa (1584-1656), who is thought to have had a very close relationship with Omuro-yaki, wrote in the section of the tea ceremony record dated March 25th of the fifth year of Shoho that “the tea caddy and water jar were both new works, and the tea caddy was shaped like a tea caddy made by Sowa was a new tea caddy with a square body and a square neck, and was made in the Ninwa-ji style. From these facts, it is thought that the opening of the Omuro kiln probably took place between October 1646 and January 1648, and not in 1647. It is also thought that the potter Kiyoemon, who later became known as Ninshō, was involved, based on an entry in the “Kakki” dated August 24th, 1649. In other words, Horin Shōshō visited the residence of Kinoshita Awaji no Kami, the superintendent of the reconstruction of Ninna-ji Temple, and said, “The potter Kiyoemon makes various types of pottery, and I also make good pottery, so I have him make water jugs, plates, tea bowls, etc. It is recorded that the people attending the meeting had Kiyoemon, the pottery maker of the Omuro ware, make vessels to their own individual tastes, and as it seems that the pottery maker did not change over the two or three years from the opening of the kiln in the fourth year of the Shouho era to the second year of the Keian era, it can be said that Kiyoemon was engaged in the construction of the kiln and other work from the beginning.

It is not clear whether this kiln was the official kiln of Ninna-ji Temple, but as people centered around the Ninna-ji Prince had their favorite works made, it seems that the kiln also had a character similar to that of a garden kiln associated with the completion of the new palace. Furthermore, it can be seen from the aforementioned “Matsuya-kai Ki” that Kanamori Sowa was in charge of instructing the potters at this kiln from the beginning, but Sowa not only instructed the Omuro potters, but also gave instructions to the Awataguchi potter Koboemon, who made the katatsuki chan-iri tea caddies, as can be seen in the “Kakugoki” dated In the entry for November 8th, 1640, it is written that “Awata-yaki tea caddies (omission)… were made by Kanamori Sowa, who was given the cutting pattern, and then made by Awataguchi Sōbei”. This suggests that Sowa was actively involved in teaching the art of Kyoto-yaki. From 1648 onwards, the Gakkei-ki mentions Omuro-yaki or Ninnaji-yaki, or Kiyoemon, Ninsai-yaki, or Nonomura Ninsai’s work, and mentions Omuro-yaki over thirty times up until the death of the author, Hourin-kouji, in 1668.

The fact that it is mentioned far more than other Kyoto-style pottery suggests that Omuro-yaki had a different character to other kilns, and it is thought that it was because it was a kiln with a connection to Ninna-ji that it was able to employ the famous contemporary potter, Ninshō.

The fact that Nisei was a master potter on the wheel and with other techniques is clear from the works that have survived, and this can also be seen from the fact that he was honored with the privilege of having his pottery viewed by the Emperor on the occasion of the Emperor’s visit to Ninna-ji on March 11th, 1660 (as recorded in the “Kakushiki”). And the fact that he mainly produced tea utensils such as tea caddies, tea bowls and water jars from the beginning can be seen in the Kakuteiki, and the surviving works also tell us this.

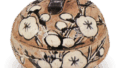

However, it is not clear whether the elegant red overglaze enamels (kinte) were being produced from the time the kiln was opened, and the first time the phrase “Nonomura Ninsei’s kinte red overglaze enamels” appears in the “Kakuteiki” is on May 4th, 1650, so before that time, it is simply referred to as Omuro ware tea tea bowls and water jars, so it is not clear whether they were polychrome or not. Of the more than 30 times that the Omuro ware and Nonomura Ninsei are mentioned, only two tea bowls are described as “nishikide”, but it is not known whether these were the only tea bowls that were polychrome, or whether the others were not, or whether the description was omitted. However, three years before the year 1657, a three-year-old incense burner with a notable inscription was made. It was an incense burner that NINSEI had donated to An’yo-ji Temple (Fig. 37), and on the bottom it is inscribed “Dedicated to An’yo-ji Temple by NINSEI, a priest from Harima, in the third month of the third year of the Meireki era”. There is also a similar unglazed shard of pottery that Ninagawa Daiichi collected from the Omuro kiln site, which is inscribed “Dedicated by Nonomura Harima… in the second year of Meireki…”, so it is clear that Nisei’s overglaze enamels were perfected between the second and third years of Meireki, and it is also possible that they were fired before that time.

The fact that the incense burner from Anyoji Temple is inscribed “Harima Nyudo Nisei” and the shards are inscribed “Nonomura Harima…” shows that a major change occurred in the status of the potter Kiyoemon. Since the Omuro kiln was opened in 1658, the name “Kiyoemon the potter” (as recorded in the “Kakitsu-ki” on August 24th, 1656), “Kiyoemon of the Tanba ware” (as recorded in the “Ninna-ji Goki” on October 9th, 1657), and “Kiyoemon the potter” (as recorded in the “Ninna-ji Goki” on September 26th, 1659) are all that are recorded as Kiyoemon’s name, but in the years 1659 and 1660 (Ninna-ji Goki, September 26th, 1655), but from the second or third year of the Meireki era, he began to sign his own incense burners with the names “Nonomura Harima” or “Harima Nyudo Ninno”. In addition, the name “Seiemon” disappears from the “Kakushiki” and is replaced by “Nin (a misprint for ‘Jin’) Sei” from then on. In other words, “Seiemon” became “Ninsei”, and he took the surname of “Nonomura” and also called himself “Harima Ido”. When you put all of this together, it seems that around 1656-1657, Kiyoemon had risen to a position where he could put the imposing title “Nonomura Harima no Daijo Fujiwara no Masahiro Nyudo Ninno” (this title is said to be inscribed on a “three-piece set of colored pottery” from 1659 in the collection of Kitano Tenmangu Shrine) on his works.

In the “Ninna-ji Goki” (a record of events at Ninna-ji Temple), he is referred to as “Tamba-yaki Kiyoemon” or “Tsuboya Kiyoemon”, and it is said that he took the surname of Nonomura, which tells us that he was from the Tsuboya pottery workshop in Nonomura, Tamba, a famous producer of tea jars, which is also mentioned in the “Kefukusa” (published in 1704). As for the name Ninshō, according to the book “Tōkō Hiyō” (A Potter’s Handbook) by Kenzan, it is a combination of the characters “Nin” from Ninna-ji and “Sei” from Seiemon, and the “Nin” from Ninna-ji was naturally bestowed by the Ninna-ji prince, and it is likely that he was also given the title “Harima Daijō” by the prince around the time he was allowed to use the name Ninshō. The reason he was given such high praise as a potter was probably because his reputation as a master craftsman had grown, and in particular, it is thought that the perfection of Ninshō’s unique overglaze enamels was highly regarded.

It is also thought that he had his hair cut in 1657, and he is referred to as “Nyudo” (a Buddhist priest), but if the fragments from 1655 had been completely preserved and had not been marked as “Nyudo”, the reason for his having his hair cut could have been due to the death of his greatest mentor in pottery, Kanamori Sowa, or it could have been due to his age, and the circumstances surrounding this are unclear.

As we have seen, the name NINSEI was not used from the time the kiln was opened in 1647, but rather from around the time of the Meireki era, as far as the available records show. If this is the case, then it is natural that the works made between 1657 and the time when he began to use the name Ninshō do not bear the Ninshō mark, and the unmarked tea caddies and other works of the Omuro ware that still exist are thought to be early works, but since there was a custom of not marking gifts or ordered works for important people, it cannot be said that all unmarked works are necessarily early.

Ninsei used five different types of seal: (1) a large seal in the shape of a small coin; (2) a small seal called an Ouchi seal or a curtain seal; (3) a small seal in the shape of a cocoon; (4) a small seal with the same design as the large seal, with the character “Sei” (清) from the name “Ninsei” written in the same way as the large seal; and (5) a small seal with a different design to the large seal, with the character “Sei” (清) from the name “Ninsei” written in the same way as the large seal. Of these, the ⑤ are commonly referred to as the Souwa seal, and it seems that there are large, medium and small versions, but this is not yet clear. However, it seems that these seals were not only used by the first Ninshō, who was a master craftsman, but also by the second Ninshō, and they were clearly also used on works of inferior quality. There are also seal stamps with Ninshō’s name engraved on them.

It is common for the techniques of potters to be passed down orally and rarely recorded, but the techniques of Omuro ware Nisei are almost entirely described in the book “Toko Hiyo” (Potter’s Essentials), a book of pottery techniques written by Ogata Kenzan, who learned pottery techniques at this kiln, and it has been passed down to the present day. According to this, there are “Hon-gama-yaki-do” (clay for the main kiln), “Goki-te-do” (clay for five-handled pots), “Iraho-do” (clay for ira-hoko), “Karatsu-do” (clay for Karatsu ware), “Setonukui-do” (clay for Seto ware), “Shiroe-beni-sara-te-do” (clay for white-painted red-dishware), etc., and the way the clays are combined differs depending on the work, but basically, the various clays are combined with “Kurotani-do” (clay from Kurodani) as the base, which is also used in other Kyoto-yaki ware.

The glazes used on the base clay also include “Hon-yaki-kake-geyaku”, “Beni-sara-te-yaku”, “Kora-yaku-no-kata”, “Tsukushi-te-no-kaki-yaku”, “Kaki-yaku”, “Shunkei-yō”, “Cha-iri-yaku”, “Seto-yō”, “Karamono-yaku”, “Cha-iri gold medicine”, ‘Shoite-cha-iri-yaku’, ‘Choko-te-yaku’, ‘Asahite-no-yaku’, as well as ‘Seiji-yaku’, ‘Seto-seiyaku’, ‘Sabiyu’, ‘Irahote-yaku’, ‘Hakeme-Matai-dote-yaku’, etc. are recorded. Some of the surviving works can be identified, while others are not, but the fact that various types of Seto-style glaze are recorded shows the general tendency of Kyoto-ware, and also supports the legend that Nonomura Ninsei went to Seto to study.

Furthermore, the “nishide-e” pigments, or overglaze enamels, are also listed, including “red”, “light green”, “navy blue (or blue)”, “yellow”, “purple”, “white”, “gold”, and “black”, all of which were used in Ninshō’s polychrome enamels.

The style of the work can be seen in the 117 diagrams, and it is possible to get a general idea of the whole picture. He made tea jars, vases, incense burners, incense containers, water jars, tea caddies, tea bowls, waste-water containers, trays, bowls, water droppers, inkstones, and screens. The wheel-throwing is truly superb, and the sculptural skill shown in the incense burners and incense containers shaped like birds and animals is also outstanding. According to an entry in the “Tokugawa Jikki” dated July 28th, 1681, not only the people of Kyoto and Kyoto Prefecture, but also the Shogun Tsunayoshi received tea bowls, vases, and inkstone stands made in the Omuro style from Ninna-ji Temple tea bowls, vases, inkstones, screens, etc. were presented to the shogun Tsunayoshi, and it is clear from the fact that masterpieces from both families have been handed down that excellent works were made in response to special orders from the Maeda family of Kaga and the Kyogoku family of Marugame, and they were also greatly admired by other daimyo.

The designs of incense burners, incense containers, tea bowls, water jars, etc. are full of elegance that could be called “city-like”, and many of the designs are based on traditional customs and practices, perhaps because they were very popular with the court nobles. Although there is no mention of them in the historical records, the most important of NINSEI’s works are the tea jars. And the fact that Nisei is the only one of the surviving Kyoto-yaki tea jars is probably because he was from the potter’s village of Nonomura in Tanba, the area where tea jars were made. According to the author of “The Old Kilns of Tanba”, Mr. Katsuo Sugimoto, the way the tea jars were made on the potter’s wheel clearly shows the influence of Tanba. The designs on the tea jars include Kano school, Sotatsu school, and Kaiboku school styles, and it seems that he probably ordered the rough sketches from painters of these schools, and the “Yoshu Fushi” (Yoshu Prefecture History) published in 1684 (Teikyo 1) says, “In the early modern period, the place where Ninshō produced his wares in front of Ninnaji Temple was called Omuroyaki, and he began to order painters such as Kano Tanyu and Eishin to paint on top of them.” In the Yoshu-fu-shi (A History of the Yoshu Province) published in 1684, it is written that “the ware produced by Ninshō in front of the temple of Ninna-ji was called Omuro-yaki, and Kano Tanyū and Eishin were ordered to paint pictures on it”, which tells us something about the situation at the time, but it is not clear whether Kano Tanyū and Eishin actually painted the pictures themselves.

As for the state of the Omuro pottery kilns, in the travel diary of Tosa Odo pottery craftsman Morita Kyuemon, who visited the kilns on August 20th, 1678, it is written, “I have come to see the Omuro pottery. There is nothing different about the kilns. There are seven kilns to see. The potter at the moment is called Kiyoemon. Kiyoemon Nonomura is the potter who is making the pottery at the moment…”, or ‘There are no other kilns at Omuro Pottery, but there are hanging vases, shakuhachi flutes, incense burners, and pheasant sculptures’, which show a part of the style of Omuro Pottery. The phrase “There are seven kilns” is interesting, but it is unclear whether this refers to the fact that there were seven different types of kiln within the kiln area, or whether it refers to the fact that there were seven rooms in the climbing kiln. Also, the fact that it says “The potter at work now is Nonomura Kiyoemon” suggests that the first Nonomura Kiyoemon may have died around this time, and that his son Kiyoemon was the head of the kiln.

Ninsei was a master potter who was active from the Shoho era to the Meireki and Enpo eras, and he is the most well-documented potter of the Edo period, but even so, the year of his death is still unknown.

There are surviving documents from the dates of February 29th, 1674 and February 12th, 1677, which are written by Kiyoemon, Nisei’s eldest son, and state that he is the borrower. Ninsei was still alive at this time, but in the diary of Morita Kyuemon from 1678, Kiyoemon is listed as the potter, so he may have died between 1676 and 1677, or he may have been alive in 1676 but had already retired. There is also a theory that he died in 1672. However, it is clear that he had died by 1695, and in the “Memorandum of Sadachika Maeda” it says, “The thirteen incense containers ordered by the Omiya have arrived, but they are not up to standard, so please remake them (omission)… . It is thought that the master craftsman, Nonomura Ninsei I, had passed away by 1695, as there is a complaint that the second Ninsei had made the incense container ordered by the Maeda family of Kaga poorly.

Ninsei appears to have had three sons.

Namely, the eldest son was Nonomura Kiyoemon Masanobu, the second son was Nonomura Kiyojiro Fujiyoshi, and the third son was Nonomura Kiyohachi Masanori. In addition, according to the “Kakui Ki” (a book of records), there is a mention of a person called “An’emon” as a child of Ninshō, but this may have been the former name of one of the three aforementioned sons. , it seems that the “Nonomura Harima no Dajo Fujiyoshi” mentioned in the “Toukou Hiyo” (A Potter’s Handbook) that taught Kenzan the art of pottery was actually the second son Kiyojiro, but the same book also records that Kiyoemon, the eldest son of Ninno, helped Kenzan when he opened his kiln in 1709. , it is thought that this Kiyoeemon was the eldest son of Kiyoeemon Masanobu, who is thought to have been the second generation, and it is unclear whether the second Kiyoeemon died young and his younger brother Kiyojiro took the name of the second Nissen, or whether the first Nissen lived a long life and taught Kenzan the art of pottery, and it was his eldest son Kiyoeemon who helped Kenzan open his kiln. , it is difficult to believe that the first Nisei, who became a Buddhist priest in 1656, was still active until 1700.

Omuro ware seems to have been produced for around 50 years, from around 1692 to 1700. , most of the works from this period bear the large and small NINSEI seals, and although they were known as Omuroyaki at the time, they were later called NINSEIyaki and highly prized. It is interesting to know how the kilns of this Omuroyaki NINSEI were run, as it gives us an insight into the nature of Kyoto-yaki in the Edo period, but it is a shame that there are almost no documents left to tell us about the situation.

However However, it is clear that the works with the NINSEI seal include those made by the first NINSEI and his successors, as it is thought that the first NINSEI did not work as the head of the kiln for fifty years, and that after the Enpo era, his sons took over the management of the pottery. Genroku It seems that, judging from the “Memorandum by Sadachika Maeda” from the 8th year of Genroku, it is a fact that the quality of his work had declined considerably by that time. And even looking at the surviving works, there are considerable differences in quality, but it is not currently possible to make a conceptual distinction between the works of the first generation, which are of superior quality, and those of the second generation and beyond, which are of inferior quality. , I tried to classify the works based on the different seals that were stamped on them to see if they indicated differences in the artists, but it was not clear, and it is also possible that the seals were used to distinguish between special products and regular products, so in short, it seems that clearly classifying the works into first-generation, second-generation, etc. is a task that is almost impossible unless new materials appear.

Here