In the Edo period, Kyoto became one of Japan’s leading pottery production centers, with kilns belching out smoke in all directions, but until the end of the Muromachi period, few famous wares were produced there. However, it was not a land completely without a connection to pottery, and in the Heian period, there were scattered kilns where unglazed and green-glazed roof tiles were fired. This tradition continued into the early modern period, with kilns in Hatae and Fukakusa producing earthenware, and mass-producing kawarake to meet general demand. It seems that Hatae earthenware was still famous in the Edo period, and in the 16th year of the Kan’ei era (1611), it was listed in the “Kefusou” as in the list of “famous products from various regions, past and present”, Hatake-doki (Hatake earthenware) is listed as a specialty of Yamashiro Province (Kyoto Prefecture), along with Awataguchi kiseru earthenware and Kurodani tea caddy earthenware. However, glazed pottery production came to a complete halt after the Heian period, and was not revived until the Momoyama period. During this time, pottery from Seto, Mino, Tokoname, Tanba, Shigaraki, Bizen, etc. met the various demands of the people of Kyoto. However, the fact that tile kilns and earthenware kilns were in use must have become a hotbed for the production of pottery fired at low temperatures, such as the Oshi-kouji ware (the actual state of the works is unknown, but it is recognized in the literature that it played an important role in the development of Kyoto ware) and the Chojiro ware, which were produced in the inner kilns.

However, in the Keicho era, it is said that a kiln for firing pure pottery was built at the foot of the Higashiyama mountains – probably in Awataguchi – and that tea caddies and tea bowls were fired there, as can be seen in the tea ceremony diary written by Kamiya Sotan (1551-1635), a wealthy merchant from Hakata who also left his name in the world of the tea ceremony. In 1605 and 1606, there are references to “shoulder-shaped Kyoyaki”, “black tea bowls, also Kyoyaki, also Hitsumu”, and “black tea bowls, also Kyoyaki”, and it is not impossible to think that these were the Chojiroyaki that were already popular at the time , but as there are no other tea ceremony records from the time that refer to Chojiro ware as “Kyoto ware”, it is thought that it was probably not Chojiro ware, but Kyoto ware, and that it was produced at a kiln that had sprung up in the Awataguchi area. And judging from various documents from the Keicho to Kan’ei periods, it is certain that the kiln was started by potters from Mino or Seto, and tea caddies by Sho’i and Man’emon, known as “Kyoto Seto” since the early Edo period, may have been made by them. It is particularly interesting that the warped black tea bowls are used as Kyoto ware, and since the so-called Oribe style was very popular at the time, it is thought that warped Kutsu-gata tea bowls were also made in Kyoto ware. And among the Kyoto Seto works from the Keicho to Genna periods, there must be some that are now considered Mino ware or Ko-gaku, and among Setoguro and Oribe-guro, there are fragments of tea bowls with a different clay taste and glaze tone from Mino ware , as well as shards of tea bowls in the black Raku style that differ from the Chojiro ware, have been excavated from archaeological sites in Kyoto, Osaka and elsewhere in recent years, and it is thought that these may have been examples of such Kyoto ware. However, at present the actual state of Kyoto ware from the Keicho to Genna periods, which can be said to be the founding period, is unclear, and we will have to wait for further research to find out more.

Furthermore, according to the book on the pottery techniques of Kenzan, “Toko Hisshiyo”, it is written that “Oshikoji Yaki-mono-shi Ichimonjiya Sukezoemon met a Chinese person who taught him the techniques of the Koji ware, and he made pottery in his kiln using these techniques. It is said that this was handed down from the founder of the Raku ware, Chojiro, but it is not known how much of this is true. it is thought that the method of Chinese-style pottery firing, which was introduced before the Chojiro ware, was already being used in Kyoto, and since Chojiro’s kilns also produced incense burners and flat bowls with Koji-tei two-color glaze, it is certain that low-temperature glazed pottery was being produced in Kyoto from around the Tensho era at the latest. Therefore, although the Oshi-kouji ware of the Momoyama to early Edo periods is not known in detail, it is thought that the techniques of the Oshi-kouji ware’s inner kiln Koji ware with colored glaze may have been passed on to the main kilns in Awataguchi, Yasaka, and Kiyomizu, and developed into the colored glaze pottery and overglaze pottery unique to Kyoto ware.

As we enter the late Kan’ei period, the movements of early Kyoto-yaki become clear from the diary of the abbot of Rokuon-ji, Horin Shōshō, which is the most important written record of Kyoto-yaki, and from other sources such as the ”

Kakushi-ki, etc., it becomes possible to clearly understand the movements of early Kyoto-yaki, and the names of the kilns, the artists, and even the styles of the works produced at the various kilns in the foothills of the Higashiyama mountains. In particular, there are many descriptions of Nonomura Ninsei’s Omuro-yaki, and it is possible to understand the style and movements of this work in considerable detail.

The first time that Kyoto-yaki is mentioned in the “Kakitsu-ki” is in 1639, and from then until 1668, when the priest Hourin passed away, the kilns mentioned include Awataguchi-yaki, Yasaka-yaki, Kiyomizu-yaki, Otowa-yaki, Omuro ware, Gohyakuike ware (the same book also mentions Bosatsuike ware), and Shugakuin ware, all of which were scattered around the foothills of the Higashiyama mountains, with the exception of Omuro ware. Shugakuin ware was a type of garden ware that was built in the Shugakuin Imperial Villa of the retired Emperor Go-Mizunoo in 1664.

At the Rogaike and Awataguchi kilns, the potters Saburo and Tazaemon were active, and it seems that at the time, these kilns mainly produced tea caddies and copies of Korean tea bowls.

The reason that many of the tea bowls made in the Kyoto style, including those made by Nonomura Ninsei, are thin and resemble the shape of Goki tea bowls is that their simple appearance was popular as a tea utensil in Kyoto at the time . Among these, the Goki-style tea bowls made by a potter called Tazaemon of Awataguchi were so good that they made the priest Horin exclaim, “What splendid tea bowls!

What is also interesting is the description of Yasaka ware, in which a potter called Seibei presented a censer to the priest Horin on May 7th, 1704, on which the character “Kotobuki” (meaning “long life”) was painted in red on the lid. If we see this as overglaze decoration, it is not only the first appearance of Nishikide-kyo ware in the historical records, but also the first Japanese red-glazed ware as far as is known. Furthermore, in December of the first year of the Shoho era (1644), Seibei also presented a “purple and blue mixed-glaze wisteria-shaped incense container” that he had made by hand to the priest Horin, but judging from the text, it was an incense container with a mixed glaze in the style of Koji ware, and since it was Yasaka ware, it was probably a fully-fired glaze, and it is thought that it was a precursor to the so-called Kosui ware that was mass-produced later. Also, the “Yasaka-yaki ume-no-mon-ari-no-hachi” bowl, which was recorded in 1656, is the first appearance of a bowl with a pattern, although it is not clear whether it was colored or rust-colored. From the above, it is almost certain that the Yasaka kiln was firing pottery with colored glazes, overglaze enamels or iron oxide designs from the Kan’ei to the Shoho periods, and it seems that the potter Seibei of this kiln was good at making pieces with a different style to Awataguchi ware.

Finally, on January 9th of the 5th year of Shouho, the Omuro-yaki tea caddies appear for the first time in the same record, and it is recorded in the “Kouguchi Sakai Ki” that from this year, Omuro-yaki began to be made with overglaze enamels and gold leaf. recorded in the tea ceremony records of Itamiya Sōfu and Kanamori Sōwa, it seems that Nisen’s distinctive, elegant overglaze ceramics were already being produced, and they are mentioned frequently in the “Kakitsu-ki” thereafter. Therefore, as far as we can deduce from the Kakitsu-ki, the development of overglaze enamels in Kyoto ware is thought to have been completed by Yasaka Seibei and Omuro ware Nisen during the period from 1644 to 1650, and other types of ware such as Kiyomizu ware, Otowa ware, Gohonzuike ware, and Shugakuin ware are mentioned one after another during the period up to 1668. Gakuen-yaki, etc., were successively recorded from the year Kanbun 8, and the production of pottery such as colored overglaze enamels, iron-brown overglaze enamels, colored glazes (Kozhi-fu), Gokite, Irahote, Shigaraki-fu, and Seto glazes began to be produced.

Looking at the production of Kyoto-yaki in the early Edo period, with the “Kakunin-ki” as the most reliable source, it seems that by the time Nonomura Ninsei’s polychrome ceramics were perfected, between the Shoho and Meireki eras, Kyoto-yaki had already developed a distinct style. Namely, the thin-walled Goki-te and Irobo-te tea bowls that were popular in the early Edo period, such as the tea caddies copied from Chinese wares and the Korean tea bowls that were fired at kilns such as Busan, were a style that differed from the wabi tools favored by Sen no were different from the wabi-style tea utensils favored by Sen no Rikyu and Oribe during the Momoyama period, and the distinct preference for “kirei-sabitsu” (aesthetic beauty) of the next generation of tea masters such as Kobori Enshu and Kanamori Sowa clearly had a major impact on the style of production.

On this foundation, unique techniques such as rusted and colored painting were invented, and delicate and elegant pottery was created that truly lived up to the term “Kyoto-style”. a major factor in the production of Mimasaka pottery was the fine, distinctive clay known as “Kurotani-do” that was produced in this area, as described in “Kefusou” and “Touko-hitsu-you”.

By the way, what is somewhat strange about the style of early Kyoto-yaki is that while Nonomura Ninsei perfected the technique of using a soft white glaze on the surface of the clay and then applying a colorful overglaze enameling in rich red, the so-called Ko-Kiyomizu ware, other than the Omuro ware, usually has a thin, yellowish-green glaze with cracks in it, and the overglaze enameling is mainly blue and green, with no red. Why did the Koshimizu ware consistently use such a subdued color scheme, when Nisei ware showed such a deep consideration for color? It is an interesting question whether the secret of the Omuro Nisei ware was such that others could not follow, or whether it was a deliberate attempt to seek a different style.

During the middle of the Edo period, that is, from the Genroku era to the Kansei era, only the Kenzan ware was shining brightly among the Kyoto-yaki wares. By the Genroku era, the glory days of Ninshō’s Omuro ware had already passed, and although kilns in the Higashiyama foothills such as Awataguchi and Otowa Kiyomizu were probably still producing work, there was no new development in style, and it seems that they were maintaining the old style while catering to general demand. There are almost no written records of Kenzan ware, and the Kyoyaki mentioned in the “Kaiki” by Kiyoharu Konoe of the Yorakuin is almost certainly the work of Ninshō, and the only mention of Kyoyaki at the time is of “a copy of the Kyōyaki Kyōgen Hakama (tea bowl)”. From this, it seems that the supply and demand of pottery was generally stable at the time.

Despite this, Kenzan’s pottery was not particularly large in scale, but it is worth noting that his unique style brought a new style to Kyoto. He studied the pottery techniques of Nisei, and in 1699, at the age of 37, he opened a pottery in the Narutaki ravine, which is to the east of Kyoto. based on the techniques of Nisei, he also added his own original ideas, and so he created the elegant and refined Kenzan ware, which was different from Nisei’s and other Kyoto-style wares. In this way, Kenzan-yaki brought a new style to Kyoto-yaki that was unlike that of Nisen or any other potter, but Kenzan left for Edo in 1731, and after that, his adopted son Inohachi (Nisen’s son) took the name Kenzan II and continued to make pottery by the side of Shogoin in Kyoto. His style was a direct copy of the first Kenzan’s style, and he also used the same signature, so over time the two styles became indistinguishable, and many of the second Kenzan’s works are now considered to be by the first.

The kilns scattered around the foot of the Higashiyama mountains, such as Awataguchi, Kiyomizu, and Gohosatsuike, produced works that were different from those of Nisen and Kenzan, and were generally referred to as Ko-Kiyomizu. These works were decorated with gold, blue, and green over a clay body covered with a yellowish-brown glaze . This style became a long-standing tradition of Kyoto-yaki, but there is a lack of materials that tell the story of the relationship between the kilns and the works, and today, when all of the kiln sites have been turned into housing, the state of the various kilns in the Higashiyama foothills is unclear. However, the mid-Edo period (18th century) was a time of stagnation in other pottery-making areas, and it is thought that Kyoto-yaki was not particularly popular at this time either. At that time, the kilns spread throughout the Higashiyama area were divided into three groups: Awataguchi, Kiyomizu and Gojozaka. The names of the Awataguchi potters known at the time include Kinkozan Kihei, Iwakurayama Kichibei, Hozan Yasubei, Obiyama Yohei, Gyozan Chubei, Kinkozan Kouzan Rakutozan Taizanzan Gyouzan Kinkozan Iwakurayama Houzan Genbei, and Rakutozan Jihei, but it is thought that they probably adhered to the conservative style of the earlier Kyoto-yaki, or Kiyomizu-style.

Sei Kiyomizu-yaki is the general name for the pottery produced in Kiyomizu, Otowa, Seikando-ji and other areas, but it seems that the scale of production was smaller than that of Gojozaka and Awataguchi, and it is also difficult to distinguish the works of each kiln here, but at Seikando-ji, Nisen-style pottery was produced.

Awataguchi The kilns on Gojozaka Street show a contrasting style to Awataguchi, and it is thought that they split off from Kiyomizu in the middle of the Edo period, but while the conservative Awataguchi style was content to continue producing the same old wares, the Gojozaka kilns were keen to develop new styles, and it was here that porcelain was first produced in Kyoto. , from the Bunka (1804-18) and Bunsei (1818-30) periods to the Meiji period, the potters who represented Kyoto-yaki included Takahashi Dohachi, Seifu Yohei, Shimizu Rokubei, Wake Kitei, Mashimizu Zoroku, and Miyagawa Kosai.

The products of the Higashiyama kilns, including Awataguchi-yaki, Shimizu-yaki, and Gojozaka-yaki, were generally sold by the Gojozaka pottery wholesalers, apart from special orders from temples, court nobles, and others. Awataguchi ware, Kiyomizu ware, Gojozaka ware and other products from the Higashiyama kilns were generally sold through the Gojozaka pottery wholesalers, apart from special orders from temples, court nobles and others, and needless to say, the main demand for these products was from the whole Kansai region centered on Kyoto.

However However, in the late Edo period, the development of a wide variety of styles centered on the imitation of Chinese ceramics, which differed from the traditional so-called Koshimizu style of Kyoto-yaki, was largely due to the fact that Okuda Eikou built a kiln in Sanjo Awataguchi under the pseudonym “Rikuhozan” and began to produce elegant porcelain-style ceramics such as blue and white and red overglaze enamels that differed from the traditional Kyoto-yaki.

Eikou was originally a merchant (a pawnbroker), and it is said that he studied pottery techniques on his own from middle age as a hobby. It is not clear when he opened his kiln, but it was probably around the Tenmei to Kansei periods. Aoki Mokumei, Kinkodo Kamesuke, the second Takahashi Michihachi (later known as Niami) and his younger brother Shuhei, and Sanmonjiya Kasukesuke, gathered at his studio, and it is likely that they were attracted by Eikawa’s imitation of Chinese porcelain styles such as blue and white and Gozu red painting.

It is Eikawa’s copies of the red-painted porcelain of the Wuzhou region were truly magnificent, and it is thought that they provided a great stimulus to the potters who came to see them. in particular, had a great influence on the hot-blooded literary figure Mokumei, who read books such as Shusekitei’s “Tosei” and studied pottery techniques himself, creating a new style of celadon, white porcelain, red painting and soft-paste porcelain such as Koji-shashin, and establishing a family of unique tea utensils. The second generation Michihachi Takahashi, in addition to the pottery techniques he had learned from his father, also became proficient in the production of Eikawa-style porcelain, and he left behind outstanding works in a wide range of pottery techniques, including pieces in the Kenzan style, Ninsai-style copies, Raku tea bowls, copies of Korean tea bowls, and sculptures such as the Jusei ornaments.

Kibai , he was one of the three most famous potters at the end of the Edo period. He in 1817, he became an adopted son of the 10th generation Ryozen Nishimura, who had been famous for his earthenware ovens since the Momoyama period, and he probably followed in the family business at first, but in the midst of the Kyoto-yaki pottery that was once again becoming popular in the Bunka and Bunsei periods, he could not have just stayed with the maintenance of the family business. Bunsei In 1827, he served at the Kishu Kairakuen Garden Pottery with his father Ryozen, and established a unique style of pottery that was a Japanese adaptation of Chinese Ming dynasty styles such as Fohua (also called Koji ware at the time), Kinrande, Kosometsuke and Shourui.

He he changed his family name from Nishimura to Eiraku, and became active as a leading Kyoto potter, and his son Zenzen was also an excellent artist who supported Kyoto-yaki from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period.

In addition , other potters active in the Kyoto-yaki world at the end of the Edo period included Kinkodo Kameyoshi, Shimizu Rokubei I, II and III, Okada Kyuta, Ryubundo Anpei, Makazu Chozo, Seifu Yohei, and the first generation of the Mishimizu and Miura families, and Kyoto became a Mecca for Japanese pottery techniques.

Kosui Mizus

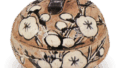

The works illustrated here are generally referred to as Kosui today, but this name is not necessarily appropriate. The term Kosui gives the impression that they are old works of Kiyomizu-yaki, but these works were fired in kilns scattered around the eastern foot of the Higashiyama mountains, from Kiyomizu-dera in the south to Shugakuin in the north. Therefore, it seems most appropriate to call it Kyoto-yaki, but when we talk about Kyoto-yaki, we have to include Ninshō, Kenzan, and the private artists of the end of the Edo period, and since these people are already treated as individual artists today, we can’t call them Kyoto-yaki anymore.

In the “Kokin Wakan Shodō Chōshū” compiled in 1694, In the “Kokin Wakan Shodogu Michisho” (A Collection of Ancient and Modern Japanese Tools) compiled in 1694, Awataguchi ware, Omuro ware, Kiyomizu ware, Kurodani ware, Oshikoji ware, etc. are listed and it is written that “all of these are Kyoto ware”, but today, many of the works of Omuro ware are considered to be Nisen ware. And Awataguchi ware, Kiyomizu ware, and the works of Yasaka ware, Gohonzakike ware, Otowake ware, Shugakuin ware, Seikanji ware, and Iwakura ware, which are mentioned in the “Kakunin-ki” and other texts, have come to be collectively referred to as Koshin ware in modern times. were made by potters who were well known at the time, according to the “Kakushiki” record, but the names of the potters have long since been lost to history. As for the kilns, although some of them are known to have stamped their marks on their wares, it is not clear where the unmarked wares were fired. are also similar, so even if you examine them in detail, it is doubtful whether you can classify them. Therefore, what is called Kosui-mizu can be said to be a generic term for the unidentifiable works of Kyoto-yaki as a whole.

It is also extremely difficult to consider the evolution of the Kosui-mizu style.

After the works of Nonomura Ninsei began to be produced around the year 1648, After Nisen’s works began to be produced around 1650, it seems that his influence was quite strong, but since Nisen’s works themselves cannot be arranged chronologically, it is naturally impossible to do the same for Kosui. However, it is thought that the typical Kosui style of overglaze enamels, which use gold and silver in addition to blue and green, was completed around the same time as Nisen’s overglaze enamels, around the Meireki era.

Many things about Kyoto-yaki from the early Edo Many things are written about Kyoto-yaki from the early Edo period in the “Kakushiki”, but there is also a travel diary written by Tosa potter Hisaemon Morita, who visited various Kyoto-yaki kilns in 1678, which describes the state of the kilns and is highly regarded as a documentary source on Kyoto-yaki.

The name “Kakushiki The name is first mentioned in the “Kakushiki” in relation to Awataguchi ware, and it is mentioned nine times between 1640 and 1660. mentions the names of potters such as Sakubei, a tea container maker, Tazaemon, who was skilled at copying Korean tea bowls, and Rihei, but it seems that at that time they were not yet making the old Kiyomizu-style ceramics with overglaze enamels. There are also six mentions of Yasaka ware between 1640 and 1650.

What is interesting about this What is interesting about this kiln is that a potter called Seibei fired a wisteria-shaped incense container (a flat, circular incense container) and a bowl with a plum design, which were the first colored glazes (whether they were overglaze or not is unknown) in the history of Kyoto-yaki, and although it is unclear whether they were iron-red, underglaze blue, or overglaze enamels, they were vessels with patterns.

Kiyomizu was first mentioned on October 22nd, 1643, and Otowa ware was first mentioned on September 10th, 1666. Both Kiyomizu and Otowa ware, it is clear from the diary of Prince Ichijō-in no Miya Masanori that they were producing flower vases, incense containers, water jars, tea caddies, tea bowls and other items in large numbers, and it seems that the Kanbun and Enpō periods were their most prosperous periods. It is also known that the Goshōin ‘s Shugakuin Imperial Villa is also recorded in the “

Kakunin is also mentioned four times between 1654 and 1666, and in the entry for January 3rd, 1663, it says “One bowl of the Bosatsuike Tenmoku, with a brocade-patterned design, with a splendid border”, so we know that they were firing splendidly colored Tenmoku.

The “Kakubai Kakushiki’ only mentions the period up to the death of Hourin in August 1668, and ‘Ichijou Shujin Nisshiki’ only mentions Kyoto-yaki up to 1690, so we can only know about the rest of the period in a very fragmentary way. In the ‘Wakan Sansai Zue’ published in 1713, In the Wakan Sansai Zue (A Comprehensive Illustrated Guide to the Three Realms of Japan and China) published in 1713, the kilns of Omuro, Kiyomizu, Kenzan and Fukakusa are listed as producing porcelain from the Yamashiro region, but only Kiyomizu-yaki is mentioned as being produced in the area around the foot of the mountains. However, Awataguchi, Gohosaiike-yaki and Oshikouji-yaki must also have been produced.

Kosei Mizusashi was said to be lacking in individuality, but there is one major characteristic to his style. This is that he rarely used red overglaze enamels, and many of his pieces were covered in a pale yellowish-green glaze with cracks in it, so his work is quite different from the polychrome ceramics of Nisei. did this style of production become established? There are so many things about Kosui that are unclear, and it is one of the important research topics for the future of Edo-period ceramics.

Eikawa

Although it is unclear what the state of the various kilns in the Higashiyama foothills was like at the end of the middle Edo period, in the second half of the 18th century, it seems that the style of pottery was generally stagnant. It was Okuda Eikou (1753-1811) who brought a new style to Kyoto-yaki and breathed new life into it. brought about a new style of pottery, which had not been seen in Kyoto for a long time, and which had only been experimented with by Kenzan for a short period. In Hizen Arita and Kaga Kutani, blue and red porcelain had already been produced from the first half to the middle of the 17th century, but in Kyoto, the traditional style of Kyoto-yaki was the polychrome pottery that had been perfected and developed by Ninsho and Kenzan. However, after the middle of the Edo period, there was a great increase in the appreciation of Chinese ceramics and porcelain from the Ming dynasty, and in particular, Koji ware, Ko-Akae-Kinrande, Ko-Somenuke, and Shouni-Goshu-Akae , etc., were highly regarded by the connoisseurs from the early Edo period through the Genroku and Kyouhou periods, and even into the late Edo period, but despite this, no imitations of these works were produced in Kyoto. Eikou appears to have been interested in making works that imitated the style of Chinese ceramics, and despite entering the world of pottery making in his middle years, he was able to successfully realize the themes he sought.

Kawa was born in 1753. family was a descendant of the Chen family, who fled the turmoil at the end of the Ming Dynasty and the beginning of the Qing Dynasty and naturalized in Japan, taking the name of Eikawa. It is said that he stayed at Seijyū-in, which is located within the grounds of Kennin-ji Temple in the Rakutō area, when he was young, but he later joined the Okuda family, a large and prosperous merchant family that was operating a business on the north side of Daikoku-chō, and became the fifth generation Okuda Shigeemon. The motive behind his It is unclear what motivated him to become a potter, but as he was a keen reader, it is thought that he probably developed an interest in the literary tastes that were gradually becoming popular at the time, and that he became deeply interested in Chinese ceramics, eventually leading him to become a potter.

However it is completely unknown how he learned the pottery techniques, and although it is generally said that he taught himself, it is thought that he probably called in artisans from the Arita or Kutani schools and learned their styles himself. Furthermore, it is also unclear when he perfected his porcelain, but there is a mark that says “Tenmei-nensei”, so it is thought that it was around that time.

The works attributed to Eikou , the style of the works is limited to five types. Namely, they are the Gozu red-on-white, Gozu blue-and-white, old blue-and-white, and so-called Ko-sansai and imitation Koji ware, and there are very few Koji ware and so-called Ko-sansai, and most of them are the other three types. , the red-painted porcelain from the Wu region is almost as good as the original, and the glaze and the lightness of the quick-drawn designs are truly superb.

However the fact that some of the shapes are Japanese-style suggests that he was not just a mere imitator, but a man of discernment. It is said that he never sold any of his works, but used them for his own use, donated them to the subtemples of Kenninji Temple where he had lived, or gave them to his friends, and for this reason they were rarely seen in the streets until the Meiji Restoration. and probably because he was a wealthy merchant and had the air of a wealthy man, people like Kibai and Dohachi gathered at his door, and because it was a hobby, he must have passed on his new skills to them without holding anything back. He was 59 years old in the 8th year of Bunka (1811).

His kiln was was located in Sanjo Awataguchi and was known by the pseudonym “Rikuhozan”. Some of his works are inscribed with the name “Eikawa” in either underglaze blue or red, and on rare occasions he also used the pseudonym “Rikuhozan” or “Yo” as a signature, but there are also quite a few works that are unmarked.

Kibai

Throughout the 300-year history of Kyoto-yaki pottery in the Edo period, the two most distinctive potters were Ogata Kenzan and Aoki Mokumei (1767-1833). Kenzan was active during the Genroku and Kyoho periods, when the court culture that had developed around the Emperor Go-Mizunoo was reaching its peak, while Kibai was active during the Bunka and Bunsei periods, when he was in contact with many literary figures and familiar with the so-called literary taste, and the styles of pottery they produced were quite different, but there is something in common in their aspirations to pottery. Both men were not potters by birth, the former having grown up in a kimono shop and the latter in a tea house, and both having entered the world of pottery from a young age. Moreover, they were both dissatisfied with the traditional style of pottery, and both studied hard to create a new style of their own, but according to the common sense of the time, they must have been considered eccentric. Kenzan created elegant pottery that made the most of the decorative painting styles of Sotatsu and his older brother Korin, while Mokume developed a unique style of tea utensils that were becoming popular at the time, inspired by the pottery of the Ming Dynasty. Mokume was born in 1767 in Kyoto, the eldest son of the owner of the tea house “Mokiya” on the north side of the Yamato Bridge on the Nawate Street in Gion. His family name was Aoki, and his common name was Sahei. His father, Sahei, was said to have been from Mino Kuguri. He was also known as Hachijyuuhachi, and it seems that he took the character for ‘tree’ from the name of his tea house and combined it with the character for ‘rice’ to create his pen name, Kibai.

Although he was born into a teahouse in a red-light district, he seems to have liked learning from a young age, and he received a literary education from Gao Fuyou. He also seems to have had a strong interest in antiquities from birth, as shown by the fact that he chose “Koki-kan” as one of his pseudonyms, and it is said that he made bronze ware and cast coins in Ise Yamada for a period in his twenties. He states in his own book, “Shouoku-den-kou-sho”, that the inspiration for his desire to make pottery came when he was staying with the first-class Osaka literary figure Kimura Koyodo, and was moved by reading “Touseki”, a six-volume book written by Zhu Yingting during the Kangxi era of the Qing dynasty, which was included in the “Ryui Hisho” book published in 1794. It is said that he read “Tōsetsu” after the age of 28, and then he entered the studio of Okuda Eikō, who was already in Kyoto and was thought to be making new pottery that imitated the blue and white porcelain and red-painted porcelain of the Ming dynasty in China, which was different from the traditional Kyoto-yaki pottery. It is also said that he studied hard to improve his pottery skills, and that he also studied under the 11th generation Hōzan Bunkō. During this time, in 1795 at the age of 29, his father Sahei passed away and he took over the family business, and it is thought that this change in circumstances was probably a factor in his decision to become a potter. However, as Rizan Yoshinaga, who was friends with Kibai, wrote in the preface to Kibai’s reprint of “Tosei” (“The Theory of Pottery”), “The old man was a man of antiquarian tastes, not a potter. He was fond of old pottery from a young age. He was not just aspiring to become a potter, but his love of antiques was the starting point, and he devoted himself to imitating the styles of ancient Chinese ceramics, and then made that pottery technique his own, creating a unique style of his own.

By the time he was 36, he was already famous for his tea utensils, which were popular at the time, and in the book “Sencha Hayashi-san” (written in 1802) by Arashi Suiko, it is written, “Sahei is a master at copying Tang-era wares”.

It is amazing that he had reached such a level of skill after only six or seven years of making pottery that he was said to be “a master of the art” or “his copying of Chinese wares is of the highest quality and also very valuable”. As can be inferred from the various biographies of Kibai, his life as a potter was triggered by his natural love of antiques, so it is easy to imagine that he must have worked extremely hard to hone his pottery skills. The fact that he had once mastered casting techniques must have been a great help in making his molded Koji ware, and the wheelwork shown in his sencha bowls is by no means ordinary.

The fact that he was appointed to serve the Aorenin-no-miya in 1805 shows that he had already become a first-class potter, and the fact that Kameida Tsuruzan came to Kyoto in the same year to invite Kibai to Kanazawa was probably because of his high reputation. He visited Kanazawa twice in 1803 and 1804, and built the Kasugayama Kiln, where he produced his distinctive celadon and red-glazed ceramics. He is also said to have been invited by the Kishu clan to participate in the Zuishiyaki pottery, but it is said that the clay was poor there and he was unable to achieve much. Kikai’s kiln was apparently located in Higashimachi, Awata.

After that, he continued to make pottery while socializing with his literary friends in Kyoto, and he passed away on May 15th, 1833 at the age of 67. As Shinozaki Kotake wrote on his tombstone, “The tomb of the literate potter Kikome”, there probably was no potter in the past who was as learned and practical as Kikome. And there are few people who could handle any kind of pottery technique as beautifully as he could. It is only natural that he is considered a genius of Kyoto-yaki pottery at the end of the Edo period when you look at the full picture of his style, and he deserves a great deal of credit for bringing to fruition the new style that Egawa opened up.

The majority of his works are sencha tea utensils. However, he did not neglect to make matcha tea utensils either, and there are excellent imitations of Korean tea bowls such as Unkaku Seiji, Hakeme, and Gohondate Tsuru. The style of the works includes Akae-Kinrande, which imitates the old red painting style, celadon in the style of Shichikante, old Sometsuke-style, Shourui-style, and others, as well as Koji ware, Nanban-yaki, and Hakudoro, and he mastered almost all of the techniques of Chinese ceramics that were seen in the world at the time. He did not just make pure copies, but also established his own style while imitating the style of the works.

The seals he used included oval-shaped wood seals of various sizes, the Seirai seal, the Kiki Kanshi seal, the Awata seal, and the Mokumai seal, as well as seals with the names “Rokumei Zou”, “Kukuri”, “Hyakuro Sanjin”, and “Sometsuke” or “Akae” written in underglaze blue or red. Many of the works are housed in matching boxes, and are signed with the seal of the Awata potter, “Awata Tōkō Rōkibaiin”, or with the various pseudonyms mentioned above.

The origin of the pseudonyms is said to be that “Seirai” is a pun on the Aoki family name, “Hyakurosanin” is a pun on the name “Moku” (meaning “wood”), which is counted as 18, and when you add 88 (the number of grains of rice) to that, you get 106, and “Kome” (meaning “rice”) is a pun on the name “Kumatori”, which is where the Aoki family came from. He also used the name of his residence, Teiunro, as his pseudonym.

Niami

Niami Michihachi was born on March 10th, 1783 in Kyoto, Awataguchi Omote-cho, as the second son of the potter Takahashi Michihachi. His posthumous name was Mitsushige. His father, the first Michihachi, was the second son of Takahashi Hachiro Daimyo, a former retainer of the Ise Kameyama domain, and it is said that he moved to Awataguchi in Kyoto during the Horeki era and began a life of pottery making, taking the name Mitsushige, the name Shuhei, and the pseudonym Shofutei Kunanaka. His eldest son, Shusuke Mitsutaka, died at the age of 19, so his second son succeeded to the family name and became the second Dohachi, and his younger brother, Shuhei Mitsuyoshi, was also later called a master craftsman. In the first year of Bunka (1804), when the first generation left the family name behind, the second Dohachi was 22 years old. When the first generation died, the second generation Do-hachi was 22 years old, but two years later, in the third year of Bunka (1804), he was given the task of serving the Aizen-in-no-miya family of Awata, so it is thought that he had already mastered the basic techniques of pottery making by learning from his father. He inherited his father’s Matsufutei name, but later changed it to Kachutei, and this name became the family name of the Takahashi family from that point on.

After that, he studied under Okuda Eikou, and in addition to the traditional pottery techniques, he also learned the porcelain manufacturing method, and it is said that he studied a wide range of pottery techniques, and also studied under Awataguchi Hozan Bunzo. His fellow students included Aoki Mokume, who had already established himself as a master potter, Kinkodo Kamesuke (1765-1837), who was about the same age as Mokume, Rakushitei Kasuko, and his younger brother Shuhei, as well as many other potters who were famous for their work in the Kyoto style at the end of the Edo period. It can be said that the Chinese-style porcelain manufacturing method that Egawa perfected through his ingenuity provided a great stimulus to the Kyoto-yaki potters, who had been stagnating.

In the 8th year of Bunka, he moved his kiln from Awataguchi to Kiyomizuzaka, and at first he made a name for himself by firing and making blue-and-white porcelain in the style of Eikawa, but if we look at his later works, we can see that he was mainly making copies of Ninshō and Kenzan rather than Chinese-style works are the main characteristic, and in contrast to Mokume’s tea utensils, which mainly imitated the styles of Chinese blue and white, red painting, and Koji ware, What is also highly regarded in the works of Do-hachi are his sculptural works, and in particular the many existing figurines of the gods of longevity, such as Fukurokuju and Jurojin, and the god of wealth, Hotei, are truly exquisite. However, from what I can see, the works that are the most outstanding are the various works that are copies of Kenzan’s works, and among these, there are masterpieces such as the Unkinte bowl and the Setsuzasa-mon bowl, and it is probably because Kenzan’s style suited his tastes.

His fame grew as he worked for the Aizen-in-no-miya family from a young age, and also for the Daigo Sanboin-no-miya family, the Ninna-ji-no-miya family, the chief priest of the Nishi Honganji temple, and successive generations of the Shogidai government officials, but in 1824 he became a Buddhist disciple of Prince Takahito of Omi Ishiyama-dera and had his hair cut off. , he opened the “Rozan-yaki” kiln for the use of the chief priest of Nishi-Honganji, and in 1826 he was appointed as a hokyaku (high priest) by the Ninna-ji temple and given the name “Nin” by the Ninna-ji temple, and was also given the name “Ami” by the Daigo-sanboin temple, and he took the name “Ninami”. Thus, the name Niami Dohachi originated here.

In the 10th year of Bunsei, he served at the Kairakuen Garden Pottery of the Kishu Tokugawa family, and in the 11th year he established the Gan-kawa-ji Garden Pottery in Izumi Kaizuka. Around the beginning of the Tempo era, he established the Ippodo Pottery for the wealthy merchant Kakukura Gennyo of Saga, and in the 3rd year of the Tempo era (1832), he was invited by the lord of the Takamatsu domain, Matsudaira Yorihiro, to establish the Sanga Pottery. Do-yaki” was established in 1832 at the invitation of Takamatsu domain lord Matsudaira Yorihiro, and he was truly active and spectacular from the Bunsei to the Tempo periods. However, in the 13th year of the Tempo era, he handed over the family business to his eldest son, Michihachi, and retired to the Edo district of Fushimi-Momoyama, where he established the Momoyama style of pottery. He continued to enjoy making pottery until his death in 1855 at the age of 73.

His works are marked with a circle with the name “Dohachi”, “Ninami”, “Ninami”, “Omuro Mitosaku”, a gourd-shaped mark with the name “Momoyama”, and a conch-shaped mark with the two characters “Dohachi” in the outline of a conch shell , and the kilns he opened each had their own kiln mark, but the San-gama kiln had one that read “San-gama Do-hachi”. Furthermore , he was the only one in the Takahashi Michihachi family to be granted the titles of “Niami” and “Hashi”, so he is particularly known as Niami Michihachi.

Conservation

Eiraku Conservation was even younger than Aoki Mokume and Niami Michihachi, and was born in 1795 in the Oriya Sawai family in Kyoto. From a young age , he was apprenticed to the centipede dealer Kimura Kobei, and it seems that he also stayed with the priest Daitoku-ji Kibai-in Otuna Munehiko, but he remained in close contact with these two people who had looked after him when he was young throughout his life, and even when he fell out with his son Zenzen and moved to Edo, he returned in accordance with the advice of these two people.

At the age of thirteen , he was adopted by the tea master Nishimura Ryozen, who had been active since the end of the Muromachi period. The founder of the Nishimura family was Nishimura Soin, who lived in Nara and was said to have prepared offerings for the Kasuga Grand Shrine under the name Nara-ya. He is said to have made tea utensils exclusively in his later years, when wabi-cha was becoming popular. Shōō, and died in 1558. The second generation took the name Sōzen and moved from Nara to Sakai to take over the family business, and the third generation, Sōzen, moved to Kyoto and lived in Rokujō Higashinotoin, and then moved again to Chūritsuri-ji, and it is said that the area was called Furo Zushi. He died in 1623. died in 1623. After the first generation After the first generation, the family continued to be known as the Tofuro-shi Zengoro, with the fourth generation being Soun, the fifth generation being Soken, the sixth generation being Sutei, the seventh generation being Sjun, the eighth generation being Soen, and the ninth generation being Soan. The third generation used a copper seal (some say it was written by Enshu) on the Tofuro, and so they were known as the Sozen Tofuro.

Conservation ‘s 10th generation head, Ryozen, was the son of Soan. After rebuilding the family home, which had been destroyed in the Tenmei fire, he lived in Aburanoji Ichijyo-bashi-zume-cho, and from his generation onwards, he began to produce not only tsubo-ro and haiki, but also other tea ceramics , and among these, copies of the “Annam Blue and White Long-Stemmed Tea Bowl” that was passed down in the Omote Senke school and the “Seto Nezuki Water Jar” that is said to have been owned by Rikyu are well known. It is thought that the sudden rise in popularity of new-style Kyoto-yaki pottery from the Kansei to Bunka and Bunsei periods was the reason for the sudden increase in the production of glazed pottery as well as earthenware stoves. Ryozen’s name was taken from that of Ryo Ryo-sai of the Omote-Senke school, and he passed away on January 12th, 1841.

Ryozen began to make pottery other than earthenware, and through the adoption of his son, his skills were further refined, and he eventually came to be known as one of the three great Kyoto-style potters at the end of the Edo period. His style encompassed all the techniques of Chinese, Korean and Japanese pottery that were popular at the time, including Koji (Hoka), celadon, Kosometsuke, Shonzui, Akae-Kinrande, Nisen-style pottery and copies of Goryeo tea bowls , and he not only imitated them, but also made his own original designs and glazes, and left behind many new tea ceramics that reflected the tastes of the times.

According to tradition , it is said that he spent around twenty years studying such pottery techniques after joining the Nishimura family until he began working for the Kishu Tokugawa family’s Oniyayaki pottery in 1827. In October of the 10th year of Bunsei In October of the 10th year of Bunsei, he was accompanied by Suiei of the Omote-Senke school to Kishu, where he worked on the garden pottery of the Nishihama villa, the secondary residence of the feudal lord Tokugawa Nariakira, and is said to have achieved great results, receiving the gold seal “Kahin Shiryū” and the silver seal “Eiraku” from Nariakira, which greatly increased the fame of the preservation of the art. thereafter, the Nishimura family began to use the “Eiraku” seal on their works, and depending on the work, they also began to use the “Kahin Shiryū” seal, and even today they continue to use both seals. The “Eiraku” seal raku” is said to be named after the Yongle period (1403-24), which was the most prosperous period for ceramics in the Ming and Qing dynasties, but this is not clear. The ‘Kahin Shiryū’ mark is thought to be named after the phrase ‘Shun tō Kahin ki kai fuku kuzan’ from the Shiki Gitei Honki, which means ‘Shun’s pottery from the Kahin region was all free from suffering and hardship’. the reason for receiving an imperial seal derived from a Chinese legend may be that the Kishu-no-kami favored the production of Chinese Ming-dynasty-style hōka in his Niwa-yaki pottery, and that the preservation of Chinese ceramics was devoted exclusively to the imitation of Chinese ceramics, such as celadon, underglaze blue, and red-painting kinrande. After receiving this After receiving the seal of the Yongle Emperor, the family used it as their family name, and Ryozan also wrote “Yongle Ryozan” on the box and stamped his seal, but it was not until the time of Wazen, the son of Hozan, that Yongle became the family name, from the first year of the Meiji era.

Yasu Shortly before he moved to Kishu, in July of the 10th year of Bunsei, he had the name “Koukei” bestowed upon him by a man named Fujiwara Mitsunobu, in addition to his previous nickname of Zengoro. The 10th year of Bunsei was a memorable year for him, as he was 33 years old.

In the 14th year of Tempou In the 14th year of the Tempo era (1843), at the age of 49, he changed his name from Zengoro to Zenichiro, so works with the inscription “Zenichiro Zou” are from after this time. In the 2nd year of the Kaei era (1849), at the behest of the Takatsukasa family he made a copy of the “Yōmei-ro” (name-raising kiln) from the Konoe family collection, and was given the two characters “Tōjun” by the Takatsukasa family in recognition of his fine work, and also took the pseudonym Tōkōken. Tōjun is said to mean the highest rank in the world of pottery. Furthermore, at that time, he was given a calligraphy scroll with the inscription “Ito Seimei” written by Prince Arisugawa Toshihito, and in honor of this, he is said to have written the two-line inscription “Ito Seimei Tōjun Ken Kawabin Shiryū Eiraku Hozon”.

However in 1850, he left his home and went to Edo due to a disagreement with his eldest son, Wazen, who was born in 1823, but he was unable to fulfill his ambitions, and as mentioned above, after the opinions of Daito and Hyakusokuya were added, he set off for Kyoto nine months later in 1851. However while staying in Otsu, his house in Kyoto caught fire, so he started making Konan ware at the request of the head priest of Enman-in temple, and he left behind works with the seals “Mitsui-gohama”, “Chotozan” and “Kahin”. Furthermore , he served as an apprentice to the Takatsuki-yaki pottery of the Takatsuki lord Nagai, but he passed away at the age of 60 on September 18th, 1854. In his later years