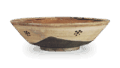

Height: 7.4cm

Diameter: 11.1cm

Outer diameter of foot: 4.6cm

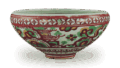

Height: 2.4cm

There are not many examples of Chinese red-painted bowls that have been used as tea bowls since ancient times. And even if there are, they are usually Ming-dynasty red-painted bowls or gold-painted bowls. So this tea bowl, called Song red-painted, is probably a rare item that is unmatched by any others. In addition, it has a unique shape called “mabou-hai”, so it must be said to be a truly unique existence.

Song red painting is the name given to the red painting produced at the Cizhou kilns from the Southern Song period onwards, and is the earliest example of Chinese red painting. As was always the case at the Cizhou kilns, the base material was covered in a white slip, and after the first firing, the red painting was applied and fired at a low temperature. The bright yellow-white background shows off the red and green colors well, and the result is a simple beauty.

This tea bowl is no exception, and shows the same style of production. As there is almost no clay visible, it is difficult to tell, but it is made using the grayish-white clay that is characteristic of Cizhou ware, and then decorated with self-made glaze. However, this shape of a “horse-riding cup” is difficult to make on a potter’s wheel, so I think that the bowl and the foot were probably made separately and then joined together. The black lacquer repair around the base of the foot is probably a repair for a joint that tends to become weak and has broken at some point. It is small enough to fit snugly in the palm of your hand, but the bowl is beautifully turned and looks fresh.

The white slip is applied all over, but only the inside of the foot remains, and the upper glaze is applied directly to the clay surface there, giving it a dark gray color. The area around the foot, where the foot is widened, is worn thin by the work of pinching it, and shows a rusty brown surface. This may be due to the effect of the iron in the clay, or perhaps the iron sand got on the fingers of the person who was picking at it and transferred to the skin. Generally, the clay used for white makeup is of poor quality, so it is easily stained, and on this tea bowl, too, there are two spots on the rim where it looks like rain has leaked in. In the case of regular Song-era red-painted ceramics, the upper red-painted layer is the only one, with no underglaze, but in this teacup, two iron-sand lines are drawn around the rim and the front of the bowl, and then the piece is fired with a water glaze applied over the top. In other words, these lines are the underglaze design. The upper line around the rim is particularly wide, and the reddish-orange color on top of the black gives it the appearance of a whale’s skin.

The red painting is not on the inside, but on the outside, which is divided into two sections, each with a simplified flower petal pattern. The colors are a slightly dull pale red and a green that is streaked in places, and the lines are red and the round dots are green. The pattern is simple, and the brushwork is careless, so it could be said that it is a generous design that is characteristic of Song red painting. The interior is plain, but there are small iron flecks scattered over it, probably from falling in the kiln. The glaze on the bottom has worn away and is rough, perhaps due to many years of use.

Although it has been called Song redware since ancient times, it is difficult to determine whether this is from the Southern Song dynasty or not, because the Song redware technique seems to have continued at Cizhou kilns from the Yuan dynasty to the beginning of the Ming dynasty. Most of the early pieces are of the normal bowl shape, so I feel that this unusual shape of a horse-riding cup may be a piece from a little later in the period. Anyway, it is certain that it was introduced to Japan from abroad, and at some point it came into the possession of the Konoike family, where it was stored together with the Hake-me Sansoku-chawan and Ido Koboku-chawan from the early Muromachi period, and has survived to the present day.