Tenmoku, celadon, painted Koryo ware, red-painted ware, blue and white ware, old blue and white ware, gosu, Shousui, Anpo-shibori-te, Beni-Anan

When did the custom of drinking tea first come to Japan from the Chinese continent? The first historical record of tea drinking in Japan is from the beginning of the Heian period (794-1185), when a priest named Eitatsu of the Omi Bonshoji temple is said to have presented tea to the Emperor Saga in the 6th year of the Kounin era (739). It is said that tea was soon planted in the Kinai region and in the provinces of Omi, Tanba and Harima, and that tea was offered to the Emperor every year. Also, at the time, Chinese poetry, which was popular among the aristocracy of the Imperial Court, often included verses praising the pleasures of drinking tea, so it can be inferred that tea was already quite popular among aristocrats and monks at the beginning of the Heian period, and it is thought that the custom of drinking tea in the Tang Dynasty had been introduced to Japan by the end of the Nara period at the latest.

It is also easy to imagine that various tea utensils from the Tang Dynasty were brought over along with the custom of drinking tea. In particular, tea bowls were the most closely associated and important utensils, and at the time in Japan, it was impossible to make beautiful bowls to match them, so naturally, bowls from that region must have been prized. According to the “Cha-kyo” (The Classic of Tea) by Lu Yu of the Tang Dynasty, the tea ceremony of the time involved grinding the tea leaves into a powder, adding this to boiling water and stirring it as it boiled, and the resulting tea was a dark red color. Therefore, when this was poured into a tea bowl, the color of the tea was judged to be beautiful or ugly depending on the color of the bowl, and for this purpose, the celadon bowls of the Yue ware kilns were considered to be the best, and the white porcelain bowls of the Ru ware kilns were used throughout the country and were praised alongside the Yue bowls. The fact that many of these celadon and white porcelain tea bowls were imported to Japan can be inferred from the fact that records of celadon and white porcelain tea bowls often appear in documents from the time, and as actual examples, although they are small in number, there are white porcelain tea bowls from the vicinity of Horyu-ji Temple that are thought to be from the Yezo kiln a white porcelain bowl, and also fragments of a white porcelain bowl have been excavated from the Otsu-kyo site in Shiga Prefecture. Furthermore, it is clear that the Sanage kiln in Tsuge-Owari copied the bowls and pots of the Etsu kiln. However after that, the word “chawan” came to be used as a substitute for Chinese celadon and white porcelain, and for example, the characters for “qing chakeng”, “bai chakeng” (vessels), “chakeng” (inkstones) and “chakeng” (pillows) can be seen in old records, and it is thought that this is because, at first, countless numbers of blue and white porcelain tea bowls were imported from China and used for tea ceremonies, and eventually the term came to be used as a common word to mean ceramics. This term continued to be used until the Muromachi period, and in the “Kindaikan Zusho-cho Ki” (a book of records from the Muromachi period), there are entries for “chakimono” (tea utensils) and “tsuchinomono” (earthenware), with celadon and white porcelain listed under the former and various types of tenmoku listed under the latter.

However In China, as the Tang Dynasty declined, the Tang-style tea ceremony fell out of favor, and from the Five Dynasties to the Song Dynasty, the Song-style tea ceremony came into vogue. In Japan too, in response to this, from around the middle of the Heian period, the Tang-style tea ceremony, which was more of a hobby, gradually fell into disuse, and tea came to be used mainly as a medicinal drink or for special court ceremonies. The old Tang-style tea ceremony , the old method was to steam the tea leaves, then pound them in a mortar without pressing out the oil, and then pack them into a mold and pound them to make a solid ball of tea, which was then ground into a powder and boiled in hot water to make a red tea. In contrast, the new Song tea method was to steam the tea leaves are strongly pressed, kneaded, and then pressed again and again until all the oil has been removed, and they are pressed and hardened into cakes until they are as dry and clean as dried bamboo leaves, that is, a faintly bluish white. In particular the tea is made by crushing the tea cake into a fine powder, pouring boiling water into the bowl, and then whisking the tea strongly with a tea whisk to create a froth, in the same way as making matcha tea. method, the tea becomes a white froth. To bring out the white color of the tea, the traditional celadon and white porcelain were not suitable. This is when black tea bowls were requested, and the Jian ware tea bowls from Jianan in Fujian were born and came to be used widely.

In the Northern Song Dynasty , the “Cha-roku” (Tea Record) written by Cai Xiang, clarifies the situation at the time, and says, “Because the tea is white in color, a black teacup is best. The teacups being made in Jian’an now are jet black, with a pattern resembling the fur of a rabbit, and the body is slightly thick. remains hot for a long time and does not cool down easily. This is the most important thing when drinking tea, and other tea bowls, whether thin or purple (satsu-iro), are all inferior to the Kenan. Even those who are experts at competing and trying out tea do not use celadon or white porcelain tea bowls,” greatly praising the Kenan. Also In the “Great View of Tea” attributed to the Northern Song Emperor Huizong, it says, “The most valuable color is a dark blue-black, and the best tea is the one with the longest and most prominent streaks of white. This there are countless other poems and writings praising the Jian Shan throughout the Song Dynasty.

This new style of tea finally took root in the monastic life of the Zen temples. The Zen priest Eisai, famous for his book “The Book of Health Preservation through Tea”, was the first to bring this Zen temple tea style back to Japan. brought with him new tea varieties, which gradually spread and took root in various places. Furthermore, the Zen temple tea culture spread to the temples of the Kegon and Ritsu sects, and was eventually adopted by the warrior class, and eventually even infiltrated the general populace. , the excellent art works from the newly opened Japan-Song trade and the frequent comings and goings of Zen monks from both countries, the number of which was enormous, were brought to Japan. The tea gatherings that were popular from the Nanbokucho to the Muromachi periods, which were characterized by their extreme opulence, were made up of art works imported from Song, Yuan and Ming China, so-called Karamono, and at the famous Hasara tea gatherings At these extravagant tea gatherings, piles of fine Chinese paintings and imported goods were stacked high, and boisterous banquets of sake and tea were held amid the luxurious interior decorations. However, as the Muromachi period progressed and we entered the so-called Kitayama period of Yoshimitsu, this uncritical attitude finally changed, and eventually, in the Higashiyama period of Yoshimasa, the world of Chinese tea utensils, which had been uncritically appreciated, came to be settled down through a methodical classification, as seen in the “Kindaikan Zuisho-cho Ki” (a record of the tea ceremony). In other words, each of the famous tea utensils found its place, and a new aesthetic value was demonstrated, giving rise to a truly noble tea ceremony using Chinese tea utensils that had never been seen before. And a new style of tea ceremony called wabi-suki was born at the end of the Muromachi period, and the Higashiyama period can be said to have been the time when the foundations for this were laid.

Now , among the Chinese ceramics that were highly prized as rare and expensive imported goods at these tea gatherings, the first to be mentioned as tea bowls are the various Tenmoku tea bowls and the many celadon tea bowls, and the following is a general description of these, and a brief description of the tea bowls that came to Japan after the Yuan and Ming dynasties.

Tenmoku

[Jian Kiln

The name Tenmoku is now used worldwide, but it originally referred to tea bowls (called Jianzan) made at the Jian kiln in Fujian during the Song dynasty, and to bowls of a similar type in Japan. The origin of the name Tenmoku can be traced to the Tenmoku Mountains, which lie on the border between Zhejiang and Anhui provinces. is home to famous Zen temples such as Zengen-ji, and the mountain range continues on to Jing-shan, which is also famous for its tea. It is said that the name Tenmoku originated from the tea bowls that Japanese Zen monks who studied abroad in this area brought back with them when they returned to Japan. gradually came to be interpreted in a broad sense, and items similar to those produced in Jianyang, as well as those produced in our Seto kilns that imitated Jianyang, were also called tenmoku, and in the end it came to be a generic term for blackish brown glazed pottery and porcelain.

The Jian kiln, which produced Jian ware was a rare kiln that exclusively produced iron-glazed tea bowls, and the kiln site has been identified as being in the vicinity of Shuichi County (formerly Shuichi Town, Jianxing County), which is now part of Jianyang Prefecture in northern Fujian Province. This were first confirmed in 1935 by the late American Professor Plummer, who surveyed the area, and then in 1954, they were surveyed again by Mr. Song Bo Yin and others in China, and the results were reported in the third issue of the “Cultural Relics and Materials” journal in 1955. According to , eleven kiln sites were discovered in the area around Chisha Village, about eight kilometers south of Shuikou County (the area investigated by Pu and the surrounding area), and at two of these kiln sites, there were traces of kilns in the form of long, narrow pipes called “snake kilns”. Also fragments of bowls with the inscription “Shangqiu 12…” (the year 1142 AD) were found at one kiln site, and at another kiln site, around 20 bowl fragments with inscriptions such as “Jinqiong” and “Gongyu” were found on the back of the foot ring. and other details have been reported, but in short, apart from the above, there do not appear to have been any important new discoveries that would overturn the existing theories.

In Japan, there are many fine examples of Jian ware, and there are many types that are rare even on a global scale. There is also an abundance of materials, and there are things that cannot be matched by others, and detailed observations have been carried out since ancient times. Jian ware The general characteristics of Kenzan ware are that the clay body contains a very large amount of iron, as is evident from the fact that it is called “tetsu-tai” (iron-body), and so the exposed parts of the ware after firing are colored brownish-red, blackish-brown, or grayish-black, giving the ware a somewhat heavy appearance. The quality of the ware varies Although it has a variety of body textures, the ones with a special and excellent glaze, such as yohen, yudeki, and usugao, are all made with clay that is either grayish black or slightly reddish brown, and the wheel-throwing technique is also more refined and precise.

The glaze also contains a lot of iron, and depending on the kiln, it can show a wide range of colors, such as navy blue, blue-black, blackish brown, reddish brown, and yellowish brown, and it is also prone to so-called kiln effects. In addition, because it is glazed thickly, it tends to run down easily, and this often has various effects on the glaze. The rabbit-hair pattern, which is common in Kenzan The rabbit-hair pattern that is common in this type of ware is due to the freeing of excess iron and the flow of the glaze.

The style of the Kenzan The basic shape of the vessels is also more or less fixed, and the four Yohen Tenmoku bowls and two Usugou bowls in the main volume are all typical examples of the Kenzan style. They are slightly deep, with a so-called “twisted rim” and a small, low, “snake’s eye” foot. Two different sizes have been excavated from the kiln site. there are also examples with a trumpet-shaped lip and a convex rim, such as the Yuteki Tenmoku in the Seikado Bunko Art Museum collection. A considerable number of these have been excavated from kiln sites, and they can also be divided into two types, large and small. Recently, there have been reports of examples of this type of slightly shallow-rimmed Tenmoku being excavated from Northern Song dynasty tombs in Wuhan City, Hubei Province.

Now in Japan, tenmoku is classified according to the glaze, into yohen, yudeki, kome (rabbit hair bowl), uru (black bowl), haihi, and kaitenmoku, etc., and of these, yohen, yudeki, and kome are all produced at the Jian kilns, and are the most important tenmoku representing Jian ware.

Yohen Tenmoku

Yohen is the most special type of glaze among the Kenkan wares, and is extremely rare. It has been ranked first among the many types of Tenmoku since ancient times. In the “Kunitai Kansuuchochoki” (Tohoku University edition), it is written that

Yohen is the best of all the Yohen bowls, and is a thing that does not exist in the world. The ground is jet-black, and there are various colors, such as light blue, white, and light blue with a hint of black, and there are also some that are like brocade, and are a thing of ten thousand.

In the same book, “Gunsho Ruijushu”, it is written

Yohen is the best of all things in the world, and is a thing that cannot be found anywhere else in the world. It is a thing that is better than all other things (it is a single medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make a medicine that is used to make . Yohen is sometimes written as “yohen”, but both are probably references to the sun, moon and stars, which shine brilliantly in the heavens. On the inside of the bowl, which is covered in a thick layer of jet-black glaze, a strange, extremely fine group of metallic crystals floats in a speckled, whitish pattern, and around the small specks, beautiful iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent iridescent ir is not something that was created artificially, but a natural occurrence in the kiln, and the unusually beautiful scenery was called yohen. In other words, yohen is also a kiln change.

Yohen are said to be the most precious and rare of all, and today there are very few of them. Strictly speaking, there are only four, including the three national treasures in the collections of Seikado Bunko Art Museum, the Fujita Art Museum and Ryuko-in, and one (an important cultural property) formerly in the collection of the Maeda family of Kaga. , there are none in China, the home of this type of ware, or in the many collections in Europe and America. What we can observe in these pieces is that, despite some differences in size and the extent of the yohen phenomenon, they all have a high level of refinement and carefulness in their wheel-throwing, and an extremely high level of dignity in their overall shape and form. , the clay used is all of a very high quality, carefully selected and grayish black, and the glaze is also a deep jet black – a dark navy blue – with a thick glaze that has a strong and beautiful luster. The crystals that float on the glaze The crystals that float on the glaze surface also show the same speckled pattern, regardless of the number of crystals, and the tone of the yohen is almost the same. However, the iridescent phenomenon of the Inaba Tenmoku in the Seikado Bunko Art Museum is particularly brilliant, giving it a unique and elegant atmosphere. In addition, the former Maeda family collection is a rare piece that has a kiln-altered phenomenon mixed in with the oil spots.

Oil Spot Tenmoku

The name “yudeki” seems to have been given in Japan, and it can be seen in various books such as Muromachi-era travelogues, “Zenrin Shoka”, “Katsuragawa Jizo Ki”, and “Shogaku Shu”. In China, the character “dixie” can be seen in the Ming-era book “Gekko Yoron”, and in one example of a recent pottery fragment excavated from a kiln site, it is named “Ginsei Ban”.

In the “Kimi Tai-kan-sau-cho-ki (Tohoku University edition)

Yudeki, the second most valuable treasure, is also a dark black color, with a light purple color, and there are many more in the world than there are in the world.

Also, in the same book, “Gunsho-suijyo” collection,

Yudeki Yohen no tsugi, kore mo ichidan no chouhou ya, joujou wa yohen ni mo ureru kara zu, go sen biki (ichibon, kore mo, yaku, tsune no ken’you ni kawari taru)

Also, in the Tokugawa edition held by the Tokyo National Museum,

Yuden, onmei ya, yohen yori wa kata, kore mo yaku yosei . In other words, Yuiteki is also a type of ware with a black glaze and many small circular spots of crystal floating on it, and the way that the small silver dots that shine blue-white or green-purple are densely packed together or scattered across the beautiful black glaze, like drops of oil, is a different kind of beauty to Yohen. It is said that the oil spot phenomenon occurs when excess ferric oxide in the glaze rises to the surface of the glaze along with air bubbles during the firing process, and eventually the bubbles burst and the crystals gather together to form the small circular spots. The oil spot on the national treasure is a representative beautiful bowl.

In addition within Yudeki Tenmoku, the crystals of these small round spots form beautiful silver streaks as the glaze flows down, creating a rabbit-hair-like pattern, or the crystals form a fascinating pattern as they flow down in a series of dots. In the “Kundai Kansuuchochoki” (Tohoku University edition),

there is a passage that reads is inferior to the crow, and the ground medicine is black, and the white gold is running, and there is also a thing that is similar to the crow, and there are also three thousand pieces

Also, in the Tokyo National Museum (Tokugawa book),

Ken’yo is written, and it is said to be a type of Yudeki, but it is actually a type of Yudeki. Hoshikenkan is probably the one that corresponds to this.

In addition there are also examples of Yudeki Tenmoku that are not from the Kenmoku kiln, but from the Hokkou kiln. These are beautiful bowls with a deep purple glaze, and reddish-brown crystals that appear all over the inside and outside of the bowl, and depending on the angle of the light, the crystals shine silver. Ryuko oil spot” ware, which is famous as a typical and excellent example of this type of ware. In this type of oil spot ware, the rim and foot ring are made to faithfully imitate the Kenjaku style, and the fact that the white clay body is covered with a matte glaze around the foot ring is a clear indication that the ware is intended to imitate the Kenjaku style. In Japan, the theory that it was produced at the Taya kilns in Shanxi has been the most widely accepted, and in the West, there is also a theory that it is a type of Henan tenmoku, but recent research has made it clear that there are no kilns of this type in Taya. It is thought that it is one of the Cizhou kilns scattered throughout Hebei, Henan and Shanxi, but at present, this is still unknown.

Tenmoku Tenmoku

Tenmoku is the name used in Japan, while in China it is called “Tohao-zan”. Tohao is a glaze with fine blue-green or yellowish streaks running down a deep dark blue-black or blackish brown glaze, giving it the appearance of a rabbit’s fur, and is far more numerous than yohen or yudeki, and is a glaze that is only found on Kenzan. , it is thought that small oil-drop crystals floated on the glaze surface and then ran down. In the Muromachi In the book “Yugaku Orai” from the Muromachi period, the names “Sei-usagohou” and “Kii-usagohou” appear, but originally, the Usagohou pattern is prone to subtle changes, and there are many variations and differences in quality in the many Usagohou bowls in circulation, ranging from deep dark blue to yellowish brown. Tenmoku is a type of tea bowl that displays a typical, extremely beautiful rabbit-hair glaze, and it also has a high level of refinement.

Chokkei

As the name suggests, this is a jet-black bowl made from a single material. In the “Juntaikansuichochoki” (Sokuhoku University edition), it is written

The original meaning is that the top glaze is the same as the foundation glaze, and there are large and small sizes, and they are inexpensive. . The word “tausan” refers to a type of teacup, but here it is written in a way that suggests a different type of kiln, so it is not clear.

There are so many kilns that produced black bowls, so it is difficult to decide on one. However, in the Kenzan kilns, there are often examples of wonderful black bowls with a wonderful glaze.

[Kenzan kiln type]

Haikatsugi Tenmoku

Also called “haikatsugi” or “haikamuri”, it is also known as haikatsugi, haikamori, haikann, haikakushi, etc. This is a Japanese name, and it first appears in the “Kindaikan Sanyocho Ki” (a book of court records).

In the Tohoku University edition of the same book,

Tenmoku: This is the usual way of making it, with the haikatsugi on top. Since it is not used by the court, it is not worth mentioning. In other versions, it is written as “hai-kakushi, a rare item in the world, with many different stories passed down by word of mouth”, or “tenmoku, with a glaze that looks like ash”.

As the name suggests, it has a glaze that looks like it is covered in ash, and although it is from the Kenmoku kiln, it is a coarser tenmoku than the works from the Kenmoku kiln. During the era of Yoshimasa were treated as inferior to Yohen, Yuiteki and Kame-me, but as the wabi-cha movement gained momentum, they gradually came to be valued, and from the end of the Muromachi period to the Momoyama period, records of various tea ceremonies frequently mention the use of haikui, and it seems that this type of tea bowl was actually held in higher regard. Taisho Meiki Kan (A Guide to Famous Tea Bowl) introduces around ten representative famous tea bowls made with this technique, and there are also many other tea bowls made with this technique that can be seen in the world today. A small number of these may be Kenkan ware. This is because the firing was insufficient, and the glaze has a whitish tone with a “raw melt” appearance. however, most of the others are made in kilns of a different type to the Ken-gama. The clay is grey or greyish-white and firm, and the glaze is often applied in two layers, with a thin yellowish-white underglaze first, and then a brown or blackish Tenmoku glaze applied on top in a haphazard manner. , the glaze often changes in the kiln, and parts of the glaze surface become darkened, as if covered in ash, or metallic crystals float to the surface, forming a luster that is said to resemble gold or silver. In the case of ash-covered glaze, this type of kiln change is particularly highly prized. The overall shape is also not as well-formed as that of Kenkan. , the foot rim is only roughly chamfered, and it does not have the “snake’s eye” shape of the Kenyo. The sharp, clear, distinct rim is a major characteristic.

Kotenmoku

This is also thought to be made in the same kiln, and the Tobitenmoku shown in this book is also a type of this. , although some of the Seto Tenmoku from the Muromachi period have a foot ring in the style of Kenzan, the majority faithfully imitate the foot ring of Haikyo. For this reason, Haikyo and Seto Tenmoku are often confused, and there are even tea books that state that Haikyo is made in Seto. It is thought that the period of Haikyo Tenmoku may be slightly later, but it is not yet clear where it was made.

In In China, excavations of old kiln sites have been carried out in various places over the past dozen years, and the remarkable results of these excavations are being reported one after another. In Fujian Province alone, there have already been more than 30 new discoveries, and of these, roughly half were kilns that fired Tenmoku ware. The following three kilns are similar to the Jian kiln in Shuixi County.

Northern Fujian Qingcun, Chong’an County, Fujian Province – Chong’an Qingcun Kiln

Caidian, Guangxi Province – Guangxi Caidian Kiln

Central Shikeng Village, Fuqing County on the coast – Fuqing Shikeng Village Kiln

Of these, the bowls from the two kilns in Chong’an and Fuqing are particularly similar to those from Jian’an, and the bowls from the Guangze kiln are said to differ only in that the clay body is slightly grayish-white. there are several other kilns that we have to wait for detailed survey reports on, but it is thought that they must also be Tenmoku kilns that are similar to the Jian kilns, to a greater or lesser extent. In other words, it is likely that the various types of Jian ware were not actually fired in a single Jian kiln in Suiyi Prefecture, but rather in a number of Tenmoku kilns centered around it.

What is even more interesting is that kilns that fired large quantities of Tenmoku that were very similar to Jian ware have also been discovered in the far north of Sichuan Province. and Gansu, and according to reports, this kiln produced various types of pottery from the Tang and Song periods to the Ming and Qing periods, but during the Song period it mainly produced black glazed bowls and cups in the style of Jian ware. The clay body is blackish yellow, the foot ring is the same type as Jian ware, the bowl shape is the same as Jian ware, and the glaze colors include jet black, black with a black glaze around the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black with a black glaze on the rim, black color, yellow haze flower black glaze, etc., and it is said that the small bowls with patterns such as rabbit fur, dripping soy sauce spots, and drifting haze clouds were all fired using a sōbachi (clay pot) and that the colors were exquisite and the workmanship was delicate. Sichuan Province, or Shu, was the birthplace of tea, and when we consider that the famous Da-Yi Kiln white earthenware bowls were in circulation during the Tang Dynasty, it is not surprising that this type of tea bowl was produced in large quantities during the Song Dynasty.

[Ji Jizhou Kiln

Taihitsu-zan

The Taihitsu-zan tea bowl is the second most famous type of Tenmoku tea bowl after the Ken-zan. The name comes from the fact that the glaze has the appearance of tortoiseshell, and it is also called a “tortoiseshell bowl”. The Jizhou Kiln was located in Yonghe, Ji’an, Jiangxi Province, and it is said that in addition to Tenmoku, celadon and white porcelain were also fired there during the Song dynasty. In 1937, it was explored by Mr. Blankston of England explored, it was discovered that, in addition to the peony-patterned bowls, white porcelain and iron-painted wares, extremely high-quality pale blue and white porcelain with carved patterns had already been produced during the Tang dynasty. Furthermore since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, it has been investigated in more detail on three separate occasions, and in the book “Jizhou Kiln” by Jiang Xianbo, it is mentioned that, along with the various types of tai-pi bowls, celadon in the style of the Yue Kiln of the Tang Dynasty and Longquan Kiln of the Song Dynasty, celadon with fine cracks (called “sai-ki”) and white porcelain in the style of the Ding Kiln , iron painting in the style of Cizhou ware, and underglaze blue were also fired, and it has been revealed that the kiln ruins at Yonghe have 22 hills of pottery shards called “kiln ridges” of various sizes, and that the scale of pottery production was unexpectedly large, and that the peak of production was during the Song dynasty, when mainly tea bowls were fired. It is not yet clear when the Jishu kilns were abandoned, but it is thought that they gradually declined as the Jingdezhen porcelain kilns flourished during the Ming dynasty.

It is thought that the It is thought that the teapot was introduced to Japan following the introduction of the Jian teapot, and that it was in use in the Kamakura period. In the “Butsui-an Komotsu Mokuroku” (a list of goods in the Butsui-an temple) from the end of the Kamakura period, the names Jian and Hakken are mentioned, along with the words “two pairs of teapots, one pair of jars, and one pair of pots”. , indicating that the name was used for tea bowls for gargling. In addition, in Muromachi-period correspondence and dictionaries, it is also known as kamizutsu, tatekamizutsu, kizamizutsu, and bessan. , it seems that the name “takebi-zame” was originally called “kamado-zame”. This is mentioned in the “Kindaikan Zuisho-cho Ki” (Tohoku University edition),

Kamado-zame, made of Tenmoku clay, in a medicine-like color, with a black medicine-like color, with a flower and bird design, 1000 pieces

Noh-kawa This is also made from tenmoku clay, and has a medicine-like color with a light purple star inside and outside, and is very cheap.

Another one is

a medicine-like star with a white clay body and a medicine-like color, and has a bird and flower shape inside the medicine.

It is also very cheap. The same as above. It is similar to sanni, and the same as above (one piece is made with black glaze).

The name of taiko-zan is finally beginning to appear. Although it is written separately from taiko-zan, they are essentially the same, and the character for “noh” is a phonetic character that is pronounced the same as “tai”.

Taiko-zan is a type of pottery with a brownish-grey body containing a lot of iron, and a blackish-grey iron glaze applied on top, and it was admired for the subtle changes in the glaze that occurred naturally in the kiln. In contrast, tai-pi-san is a highly technical piece that cleverly combines a dark black glaze and a yellowish-white translucent glaze on a grayish-white base, aiming to create various pattern effects. The candy glaze is a fine seaweed-like glaze, similar to the ash glaze commonly known in Japan as warashiro. In Jiang Xianbo’s “Jizhou Kiln”, there are many bamboo groves in the Ji’an area, and it is thought that bamboo ash was used.

The basic technique of making a soft, furnace-shaped glaze by applying yellowish-white ash glaze in spots to a black glaze and melting it to the right degree in the kiln is the basic technique of making a tai-pi bowl. If the melting is excessive, it becomes a so-called tiger-skin pattern, and if it is insufficient, it becomes a dotted pattern. It is also possible to freely draw various patterns on a black background using this ash glaze. There are many examples of simple plum blossoms, various flowers, and lighthearted depictions of flowers, birds, butterflies and insects, and there are also some unusual examples, such as those that combine arabesque lines into heart shapes. However, the most prominent feature of tai-pi-shan is probably the patterning technique that uses the stencil paper craft technique. For the simpler pieces, the paper stencil is placed on the base material, covered with black glaze, and then fired after the stencil is removed. However, the more common method was to place the paper stencil on the black glaze, spray on a second layer of ash glaze, remove the stencil, and then fire. The effect of the paper stencil appearing in black against the warm, translucent seaweed glaze is also very unique.

The paper cutout patterns show a wide variety of variations, including folded branches of flowers and scattered floral patterns, as well as auspicious characters, birds and phoenixes, dragons, deer, and butterflies. All of these represent auspiciousness, and the plum blossom pattern, which symbolizes spring, is often seen, as is the flying phoenix pattern. The characters, which are arranged in a diamond-shaped window frame, are arranged in three directions, with four characters each for “gold and jewels in abundance”, “long life and wealth”, and “happiness and health”. These three are relatively common, and in recent years in Japan they have been named “plum blossom tenmoku”, “luan tenmoku”, and “character tenmoku”, and admired.

Origami paper craft was originally widely popular in China, and was already popular in the Tang Dynasty. It is still handed down in various places today, and is particularly popular in the Jiangnan region. The application of this technique to pottery patterns was the wisdom of the pottery artisans of the Jizhou kilns in the Song Dynasty, and together with their outstanding glaze techniques, it can be said that they further enhanced the reputation of the Gaho-zen ware.

What is even more unique about this kiln is the so-called Mokuha Tenmoku, which uses real leaves. This is a new technique in which a single leaf or several leaves are placed on a black glaze and fired, and it is a technique unique to this kiln that is unlike any other. Recently, it seems that this method is being tried out in various ways in Japan, and there are a number of different methods, such as simply sticking down a particular type of leaf and firing it, or applying a white glaze to the leaf and sticking it down , or the method of boiling the leaves in caustic soda solution to make them into leaves with only fine reticulated veins, then dipping them in white straw glaze and attaching them to the surface before firing. All of these methods produce a kind of Mokuhyo Tenmoku, but it is difficult to achieve the same level of realism, and it is impossible to hope for something as good as Mokuhyo Tenmoku. At the “Jishu Kiln” of Jiang Xianbo, they first decide on the places where the leaves will be attached to the surface of the clay body, and then apply a yellow glaze to these places. After that, they attach leaves that have been corroded by soaking them in water, and then apply a black glaze to the entire surface before firing. However, it is difficult to expect a clear leaf pattern using this method. Anyway, whether it’s this Mokuhyo Tenmoku or the Senkizome pattern of the aforementioned Nembutsu-do, the warm, unique black glaze with its soft, seaweed-like amber glaze that changes subtly in a thousand different ways, from yellow to blue to green to brown to purple, is utterly captivating. As with the Kenyo collection, the Tsukikawaya collection featured in this volume is made up of particularly outstanding bowls that have been handed down in Japan since ancient times, and are rare masterpieces that cannot be found in China or the West.

Celadon

Longquan ware

The fact that far more celadon from the Southern Song dynasty was imported to Japan during the Kamakura period than had been imagined is demonstrated by the countless fragments of celadon that have been excavated from archaeological sites around the country, including the Kamakura Zaimokuza coast and Kitakyushu. It is also well known that the majority of these pieces are Ryusen ware celadon. In addition to these excavated shards, there are also a number of complete pieces that have been handed down, and among these, the superior works known as Kinuta celadon occupy an important position, and today, many jars, bowls, plates, and incense burners are carefully preserved and passed down as rare treasures. In the world of tea bowls, tenmoku was held in the highest esteem, and celadon tea bowls were considered to be of a lower order. However, the extraordinary popularity of celadon did not mean that tea bowls were particularly neglected, and until the end of the Muromachi period, they were highly prized alongside tenmoku. Of these celadon tea bowls, the first to be singled out were the so-called Kinuta celadon from the Ryusenkama kiln. The “Baikoukan”, “Mangetsu” and “Uryu” tea bowls are representative of this type.

Several surveys of Longquan Kilns had already been conducted before the war, and the general outline of the kilns was known, but after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, further surveys were conducted several times, and more detailed facts were revealed. According to this, the Longquan Kilns are extremely extensive in scale, and consist of a group of 200 ancient kiln sites spread across the counties of Qingyuan, Yuhua, Suichang, Lishui, and Yongjia, with the main group of kilns located in the Longquan County area in the southwest of Zhejiang Province, close to the border with Fujian Province. The largest centers are the various kilns in Longquan County, such as the Da Kiln and Xikou, as well as the Jinkun and Zhukou kilns in Qingyuan County, which were established in the 5th century and are known to have been influenced by the Yue kilns at the time. After that, it passed through the Northern Song dynasty and reached its peak during the Southern Song dynasty, and the most outstanding works of our familiar Qinzhou celadon ware were produced at the large kilns centered on the Jin Village kilns. Also, among the pieces that appear to date from the Northern Song period, there are bowls with a five- or six-lobed rim, known as “kikizawa” bowls, and it is worth noting that the “Mahoukan” bowl is very similar to these. At one time, it was thought that the Ma Huang Jian might have been made at the Southern Song Guan Kiln, but this suggests that it was probably made at the Longquan Kiln during the Northern Song period, or at least around the time of the Northern Song. The “Shinogi tea bowl” with the Kinsei celadon glaze and the “Mangetsu” (full moon) inscription is a type that is often found in the same shape, and similar examples can be seen in the pottery excavated from Jinkun during the height of the Southern Song period.

According to the research report, “The Longquan ware of the Northern Song Dynasty has a transparent glaze, with a light blue color tinged with gray. The shape is simple and the corners are clearly defined. The foot ring is wide and straight, and the base is unglazed. In contrast, the white-bodied celadon porcelain (refers to ordinary celadon porcelain) of the Longquan kilns of the Southern Song dynasty has a fine, dense body, and the color of the base is white with a hint of blue. The shapes break away from the Northern Song style, combining softness and clarity, and the floral patterns have a distinctive style. The glazing technique has advanced even further than in the Northern Song, with a thick glaze layer and a brilliant color. The glaze colors include powder blue, plum-blossom blue, blue-brown, blue-gray, gray-yellow, crane-skin yellow, honey-bee yellow, sesame paste yellow, and light blue. Of these, powder blue and plum-blossom blue are the best, with a brilliant and lustrous color like a beautiful jade dragon.

What is even more remarkable is the fact that, from the kiln sites at Xikou in Longquan County, a number of pieces of celadon with a dark, thin body and a thick, multi-layered glaze, and with many cracks, were excavated, which we had previously identified as being from the Southern Song-era Guotang official kilns. In China, this is called a black-bodied celadon jar, and it is said that this is exactly what should be called a Ga kiln.

As there is a need for a re-examination of the Southern Song Guan ware, this discovery provides an important issue, and for example, the celadon with craquelure called kan’yo (government use, government kiln, government palace, rust kiln, and Tachi-hata, etc.) that frequently appears in Muromachi period records must be considered in relation to this. In addition, among the bowls named “Matsumoto tea bowl”, “Hikisetsu tea bowl”, “Yasui tea bowl”, “Zenkou tea bowl”, or “Kounoden tea bowl”, there are many interesting questions that need to be reconsidered, such as which of these bowls were made at the Longquan kilns or government kilns, and which of the celadon tea bowls that have survived to the present day can be confirmed as having been made in government kilns, etc., there are many interesting questions that need to be reconsidered.

Shuko Celadon

This is a tea bowl that is said to have been loved by Murata Shuko, the founder of the wabi-cha tea ceremony, and is not a beautiful celadon bowl like a kinuta-te, but a rough bowl with a light grayish-yellow glaze that has oxidized, and so-called hishi-te, with light combing and scraping marks called neko-gaki running on the inside and outside. have been highly prized since the time of Shuko, and there are a number of famous bowls that have survived to the present day. According to the records,

Shuko tea bowl, made of celadon porcelain, with a pattern of Chinese flowers, and some of them are made to look like hard-paste ware (from “Mekiso”)

Shuko tea bowl, made to look like hard-paste ware, with carved patterns, light yellow in color (from “Meikiroku”)

Shuko It is said that the tea bowl is a Chinese tea bowl with a persimmon-colored body and a vertical line on the outside, and that it is also called “kobukura”. There are many old examples, and there are still some in existence today. You should be aware of this (Chado Shoden-shu).

Shuko It is said that the tea bowl was owned by Shuko, and that it is actually a Ko-cho ware tea bowl, and that it is called a Ko-cho tea bowl in old books. Looking at the clay, the clay is very hard.

The Ko-cho In the “Tea Utensils Compendium”, the words “Kouchi tea bowl, Kouchi tea bowl” can be found, and it seems that Kouchi refers to Koji. In other words, the coarse celadon bowls that came from the south are called Kouchi tea bowls, and it is thought that Shuko celadon is also included in this.

Also , many shards of what appear to be jade-glazed celadon, along with other celadon from the Southern Song period, have been excavated from places such as Kanzeon-ji Temple in Fukuoka Prefecture, Fukuoka City, Karatsu in Saga Prefecture, Kusado-sho in Hiroshima Prefecture, the southern suburbs of Kyoto, and the coast of Kamakura, and among these are also small plates. in recent years, it was thought that these jade-glazed celadons were probably made in Zhejiang Province during the Southern Song period, somewhere other than Longquan. However, recently, Chinese scholars have discovered that many of these types of celadon are included in the detailed surveys of old kiln sites in various parts of Fujian Province.

In Fujian , in addition to Tenmoku, there are surprisingly many kilns that fired coarse celadon, and the kilns that fired bowls of the same type as the jukō celadon must first be mentioned as those in Songxi County. Songxi is a county in northern Fujian near the border with Longquan in Zhejiang, and from the kiln sites here, coarse celadon with the same cat scratch pattern as the jade-glazed celadon has been excavated.

Furthermore, it is thought that these kilns span the period from the Five Dynasties to the Northern Song Dynasty, and may be the source of the jade-glazed celadon. Ceramic fragments from this area were displayed in Japan a few years ago. , it is reported in the journal “Bunka” (1965, No. 9) that kilns of the same type, which are thought to belong to this lineage, are scattered in various prefectures along the coast of Fujian, including Lienchiang, Fuqing, Quanzhou, Nanan, Tong’an and Tanpu. It is thought that they were probably exported to Japan in large quantities from the Quanzhou area as a type of general merchandise during the Kamakura period.

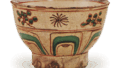

Celadon Hand-painted

dolls are impressed on the inside of tea bowls, and many of them are crude celadon ware that has been fired to a loquat-colored finish using an oxidizing flame. Most of them have a plump bowl-shaped form, but they have a high foot ring and are thickly made overall. are often decorated with characters, clouds, flowers, etc., as well as figurines. The exterior is almost always plain, with the exception of a few pieces that have a band of thundercloud patterns around the rim, and there are also examples of both the interior and exterior being completely plain. , and examples of this can often be seen in Longquan ware from the Yuan and Ming dynasties, but this is the main characteristic of Ningyo-te celadon. The period is thought to be around the middle of the Ming dynasty, and although the exact location of the kilns is unknown, it is thought that they were located near the coast, either in Zhejiang or Fujian.

In an old In an old tea ceremony record, the “Ninin-chawan ni chadachi-kou” (two doll tea bowls for tea ceremony) entry in the tea diary of Tsuda Sōyū, dated April 25th, 1568, seems to be the first record of this type of tea bowl. This was during the second year of the Ming dynasty, so it is certain that it was introduced to Japan before that time. afterwards, they began to appear frequently in tea ceremony records around the Tensho era. Among them, the doll-shaped tea scoop (formerly owned by the Konoike family) that Sen no Rikyu treasured is particularly famous. In the “Taisho Meiki Kan” (Great Tea Bowl Collection of the Taisho Era), Meiki Kan (A Guide to Famous Tea Utensils of the Taisho Period) introduces other famous pieces in addition to the doll-shaped tea utensil owned by Shōan, including pieces from the Ko-eji family in Nagoya, the Matsuoka family in Kanazawa, the Murayama family in Osaka, and the Umakoshi family in Tokyo. From this, we can see that they were much prized up until the Taisho period, but not so much in recent times.

E-Kōrai Cizhou ware

It is now common knowledge that the tea bowls known as “E-Koryo” were not actually made in Korea, but were in fact white glazed black flower patterned tea bowls made in the Cizhou kilns of China. This misnomer arose from the fact that in the old days, when knowledge was limited, the black flower patterned Koryo celadon ware was confused with the black flower patterned Cizhou ware. , and there are also other examples of white porcelain from the Dehua kilns in Fujian being mistaken for white Goryeo ware. Even in the Taisho Meiki Kan (A Guide to Famous Vessels of the Taisho Period), E-Goryeo ware is included in the section on Joseon tea bowls, and there is no doubt that people believed that the ware from the Cizhou kilns was Goryeo ware. name has been passed down to the present day, and it has become a widely used common name. The earliest appearance of the name ‘E-Koryo’ is in the ‘Enshu Zocho’ (Enshu’s inventory of tea bowls), which lists tea bowls with Enshu’s calligraphy on the box, but it is thought that the name may have appeared even earlier than that.

The Cizhou ware was produced in large quantities from the Ming and Qing dynasties to the present day. The kilns from the Song dynasty are located outside the town. The products were mostly so-called ‘painted Koryo’ ware, which had a gray or grayish-yellow body with a white slip and a roughly drawn black pattern in iron pigment. In recent years In a recent survey, a large-scale kiln site spanning the Song, Jin and Yuan dynasties was discovered in Yaguo City, Hebei Province.

There are countless varieties of black-flower patterned tea bowls fired in these Cizhou-style kilns, but the ones that were once favored by our tea masters were naturally limited, and the so-called “picture When we talk about Koryo-style tea bowls, we are usually referring to shallow, flat tea bowls with the seven-day pattern scattered around the outside and a snake-eye-shaped openwork section on the inside, which is known as the umebachi tea bowl. the seven-day pattern called the umebachi pattern was already a popular design at the Cizhou kilns in the Song dynasty, but in this case, it is not thought to date back to the Song dynasty, and judging from the design of the eye of the snake on the inside and the plain foot ring, it is thought to date from the Yuan or Ming dynasties. However , the smooth style and the refreshing feeling that can be felt even in the roughness of the workmanship may be said to be in the style of Enshu. In Kazuo Kusama’s “Tea Vessel and Tea Utensil Illustrated Collection”,

the painting are also foreign, from around the Wanli era, and are said to be from Korea (omission)… The tea bowls are all thin and flat, with black designs on the outside and plain designs on the inside, like a snake’s eye, without any glaze, and they look like they have been fired in layers and a little bit of a convex shape, without a design, plain, with black glaze around the foot ring, a little larger in appearance, these tea bowls are rare, and there are probably more right-hand bowls and fewer deep ones

. . In addition to the umebachi tea bowl, the Taisho Meiki Kan also lists a deep bowl with an outer black glaze and an inner design of fish and aquatic plants and the eight trigrams, but this is a crude bowl from a later period.

The most unusual of the E-Koryo tea bowls is the umajō-hai, a tea bowl with red overglaze enamels. ware, called Song red-glaze ware, are highly prized for their vivid red and green overglaze designs. All of these are recent excavations and are not generally used for drinking tea. However, this tea bowl, which was passed down in the Hongoike family, is a rare example of a tea bowl used for preparing tea that was stored in a tea box. However, it is not a clear example of Song redware, and its shape and the fact that it uses both black and red designs suggest that it was probably made in the Jingdezhen kilns in the Yuan or early Ming periods.

The name “majo-zen” is already recorded in Muromachi-period documents such as the “Gakushu-shu” from the first year of Bun’an, the “Shokai-shu” from the Kyouroku era, and others such as the “Onko-chishin-sho” and the “Unpo-shikuyou-shu”, as a type of Tang tea bowl , and in the “Kundai Kansuuchochoki” (Tokyo National Museum edition), it is recorded as a type of sake cup, with the words “Haijo-zame and Kenjo-zame are similar”. Haijo-zame was originally a type of sake cup, and there are also large versions from the Yuan and Ming dynasties that can be used as tea bowls.

Undo Hand-painted (underglaze blue and old red overglaze enamels)

Jingdezhen Kilns

The Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi, which had been producing white porcelain and blue-and-white porcelain since the Tang and Song dynasties, perfected underglaze blue porcelain during the Yuan dynasty, and at the beginning of the Ming dynasty, they made further advances in this area, while at the same time mastering the technique of overglaze enameling, or red overglaze enameling. is said to have been introduced from the Cizhou kilns. The success of this blue and white and overglaze enamelled porcelain opened up a new phase in the future trends of the ceramics world, and from this time onwards the Jingdezhen kilns achieved unprecedented development, becoming the largest center of Chinese ceramics.

This porcelain from Jingdezhen was naturally welcomed in the tea ceremonies of the Muromachi period, which worshipped Chinese imports. Jingdezhen was known by the name of Ryoju at the time, and the Ryoju Kō and Ryoji that appear frequently in Muromachi-period documents are none other than Jingdezhen porcelain. , “Dingzhou”, “Dingzhou Yinru” and “Dingqi” are now interpreted as referring to the white porcelain of the Fangding kilns in Jingdezhen, rather than the Dingzhou kilns in Hebei.

Many , but even in those that simply say “Rao Zhou Keng” or “Rao Ji”, it is likely that they also included blue and white porcelain. And it seems that the majority of these were tea bowls, so it can be imagined that a considerable amount of white porcelain and blue and white tea bowls were being produced at the time. However it is actually very doubtful whether these were actually used as tea bowls for drinking powdered green tea, and they were probably used as tea bowls for rinsing the mouth or as teacups.

At the time , the Tenmoku tea bowl was by far the most popular for tea drinking, so there was no room for these to be used as tea bowls. However, some of them were re-introduced as tea bowls for tea drinking after the new style of tea developed by Kobori Enshu and others in the Edo period. The Undote tea bowl is a prominent example of this.

The name Undote takes its name from the design on the side of the vessel, which depicts a building in the clouds. This type of underglaze blue, which is thought to be the origin of the Undote style, can be seen in the thick underglaze blue wares produced at Jingdezhen’s civilian kilns from the beginning of the Ming dynasty onwards, from the Xianfeng period onwards. There are many large jars and bottles, and on rare occasions, thin, exquisite bowls can also be seen. It is thought that they were produced at the Jingdezhen kilns during the period known as the ‘blank period’ of the Ming dynasty (1436-1434), but they can be seen to have been produced over a much longer period than that.

The most striking feature of this the most striking feature is the distinctive human figures depicted. Many of these paintings depict mounted warriors, such as those in the “Three Kingdoms” series, which are commonly referred to as “knife and horse people”. There are also many works with a rich literary taste, such as those depicting the four arts of koto, shogi, calligraphy and painting, or the leisurely strolls of literati in the mountains, as well as works depicting Taoist immortals such as the Queen Mother of the West and the Immortals of the West. all show a strong, wild charm in their brushwork. By the way, there is one feature that can be seen in almost all of these compositions. This is the cloud shapes that flow across the background of the picture, sometimes depicting a scene where the clouds are rising and flowing in abundance, symbolizing the flow of the story. , they are used to indicate that the area is a sacred and pure place, or to divide up the screen.

In large vases, there are often examples of tall buildings depicted in such cloud-like patterns, and this is a simplified version of that. There is a tendency to include these kinds of cloud-like patterns in the so-called Kosometsuke. , Kosometsuke is actually a later style and is not the same as this. It is thought that they were mistakenly confused.

This Undote style also includes a type of simple, yet rich red-painted tea bowl called “Koakae”, which is also highly prized in the world of Japanese tea ceremony. Koakae painting is mainly red and green, sometimes with yellow, and generally has a rough, quick brushwork and large patterns. It is also clearly made in Jingdezhen’s private kilns, and the body glaze is not as clear as that of the official kilns. are mostly designs that use only overglaze enamels, and even when they use underglaze blue, the blue areas are small and only used as a supporting element. The term “old red painting is called, whether it means “old imported red painting” or whether it is just a vague reference to old-fashioned red painting, it is clearly distinguished from the Five Colors of the official kilns of the Jiajing and Wanli periods, and it is also different from the later Tianqi red painting and Nanjing red painting. country, there are quite a few tea bowls, bowls, plates, vases, incense burners, etc. that have been handed down as tea utensils.

It is not yet clear when these old red-painted wares were made. From their designs and forms, they roughly overlap with the end of the period of the aforementioned underglaze blue and cloud-patterned wares, and the lower limit is in the Jiajing period. There are some with There are some with the name of the Jiajing era, and there is also a small dish with the rare “Tembun Nenzo” blue and white inscription from the Muromachi era. The “Tembun” era spanned from 11 to 33 years of the Jiajing era, and it is thought that these were specially made with the Japanese era name as a trade item for Japan at the time. Among these old red-painted wares, the Undote tea bowls appear to be relatively old.

In the Undote teacups, whether they are underglaze blue or old red painting, there are two types: one is called “hachinoko”, which has the same design and shape as a teapot, and the other is a cylindrical shape. The cylindrical shape was originally created as an incense burner, but was later applied to teacups. , those that depict a standing figure in the cloud design are called “Kimiidera” in the tea world and are highly prized. In addition, as variations on the Undo design, there are also the Undoryu (cloud dragon) design, which depicts a dragon in the clouds, the Unsote (cloud grass) design, which incorporates arabesque patterns in the clouds, and the Matsubakume (pine, bamboo and plum) design, which depicts pine, bamboo and plum, and there are also rare examples with landscape and figure patterns. are all old styles, just like Undo-te.

Kosometsuke

In the world of Japanese tea ceremony, what is called Kosometsuke or Kosome is neither the early blue-and-white porcelain of the Yuan and Ming dynasties, nor is it truly old blue-and-white porcelain. In fact the distinctive, sketchy blue-and-white porcelain produced in Jingdezhen around the end of the Ming Dynasty and the beginning of the Qing Dynasty was called “kosometsuke” (old blue-and-white), and this included special blue-and-white tea utensils ordered from Japan and favored by tea masters. Recently, these have gradually been sorted out, and when referring to “kosometsuke,” the latter is specifically referred to. The former is called “Tenki-sen-zoku” and is now distinguished from the former.

From the end of the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty From around the end of the Wanli era, the Jingdezhen kilns finally showed signs of decline, and by the time of the Tianqi era, the techniques had suddenly become rough and crude. This was because the protection of the imperial court had waned, and the strict framework of government supervision had also disappeared, but on the other hand, the potters were freed from the standards of the official kilns and were able to engage in production freely. the blue and white and red overglaze enamels that emerged from this were created and painted freely, using crude materials and techniques, and sometimes displaying a sense of wild abandon, and thus developed a unique style known as “Tenkei-fu” (divine inspiration style). , these crude products were exported overseas in large quantities, and a large number of tableware items were also brought into Japan. Even today, there are countless examples of Ming- and Qing-dynasty blue-and-white and red-paint tableware that remain.

It was our tea masters who were the Japanese tea masters who grasped the unique charm of this Tenkai-style pottery and skillfully applied it to tea. This was a time when the distinctive and elegant style of Oribe was very popular in the tea world, following the style of Rikyu, and it is not difficult to imagine that there was a great deal of interest in the Ming-era blue and white pottery. such tea masters eventually became dissatisfied with their selection of ready-made utensils, and actively requested the production of tea masters’ favorite porcelain in that area, for example, by showing designs that were Oribe- or Enshu-style, and placing special orders.

Those are varied and rich in content, including vases, water jars, incense containers, tea bowls, and dishes for kaiseki cuisine, but there is a certain type that has naturally been established, and for vases, for example, the shape of the vases called “Takasagote” made of Kinuta celadon, which depict people and waterweed, are prized. Also the “sangokute” type of vase is a copy of the Song celadon style, and the “hishiguchi” type of vase is a variation on the shape of bronze vessels. Water jars , such as cherry blossoms, bamboo, buckets, buckets with handles, grapes, octagonal grape trellises, potato heads, and buckets with handles, are boldly incorporated into the tea master’s favorite styles of Japanese-style maki-e lacquerware and lacquerware, as well as the styles of Joseon and Nanban pottery. Incense containers , there are many types of molded incense containers, and there is also a wide variety of bowls, serving dishes, etc. that are heavily influenced by the Oribe style. There are relatively few types of tea bowls, and there is no such thing as a standard shape. Rather, many of them are bowls, serving dishes, or fire-irons that have been converted into tea bowls. The picture tea bowls originally had a crown with auspicious patterns, which symbolized the promotion of a man to a higher government rank, and the pattern of the crown scattered around the bowl is interesting. Other examples of the use of cylindrical incense burners include the Gosho-guruma, Shumaijin, and Hahahatori. When it came to purely Japanese-style subjects such as the Gosho-guruma, the potters of the region seemed to be at a loss, and the appearance of the carriages and attendants became strange, which in turn added to the interest. In this respect, the red-lacquered Shiba-uri and babadori are purely Chinese subjects, so the only thing that can be said about them is that they are interesting for the way the brushwork has broken down. The babadori can be replaced with a dragonfly or a butterfly design. Incidentally, there is also a theory that these hi-ire were originally produced as cylindrical tea bowls, and then converted to hi-ire. Or perhaps that is the case.

Shourui

Among the blue and white porcelain produced for the Japanese market by the Jingdezhen kilns at the end of the Ming dynasty, there is a special high-quality tea bowl called Shourui that is highly regarded.

Unlike the rough workmanship of old blue and white porcelain, the body, glaze and blue pigment are all of a high quality, and the deep, vivid blue of the porcelain cannot be achieved with any other imported Western blue and white porcelain. There are various types of Shōzu, but the standard works include the mandarin orange-shaped teapot, the gold-dust bag-shaped water jug, the various molded incense containers, the warped bowls, the hand-held bowls, the suhama-shaped bowls, the cylindrical , square, and clogs-shaped serving dishes, etc., are decorated with a rich variety of auspicious Chinese-style patterns that fill the entire surface of the vessel, and are designed in a way that is a blend of Japanese and Chinese styles. And on the typical pieces, there is usually a blue-and-white inscription reading “Goryo Taifu, Goshoryu Zou”, and this has led to the theory that Goshoryu was made by a Japanese person. However, recently, it has been suggested that Goryo Taifu should be read as Goro Dayu in the Japanese style, and that he was a Chinese person who took the surname Goryo and the name Goshoryu, and that he belongs to the Wu family and his name is Shonzui, and that he produced it using the special design of the Japanese order from the time of Emperor Shouchou, using the material of the Chinese tea tree, and that it is a new theory that should be listened to (Shonzui, a treatise by Kikutaro Saito, “A New Theory of Shonzui”, published by the Yamaguchi Teikyu Museum).

The most appropriate standard work for determining the era of Shonzui is the tea cloth tube with the inscription “Sutei” in the collection of the Yamaguchi Teikoku Art Museum. This clearly states the seven-character couplet praising the imperial official’s wealth and the year of the Sutei era, “Kinboudaimei daitouka, ippon aoi shouri, daimyou sutei hachi nen tsukuri”. According to the above theory by Mr. Saito, there is evidence that a large amount of Persian blue was sent to China by the Dutch East India Company during the reign of Emperor Shōtei, and in line with this, there is also the fact that a large number of blue-and-white porcelain dishes made with Persian blue were exported to Europe during the reign of Emperor Shōtei. The reason why the Shourui ware is richly decorated with the beautiful blue of the Persian blue, as opposed to the murky blue of the Tenkei-made earthenware blue, is precisely because of this.

Now, just like the old blue and white ware, very few tea bowls were made in the Shōzu era. On rare occasions, you can find cylindrical teacups rather than the so-called bowl-shaped ones. However, this shape is not very suitable for drinking tea at a tea ceremony, and the small ones are only good enough to be used as tea bowls in tea boxes. The polka-dot tea bowl in the collection of the Nezu Museum is also famous, but looking at the overall design and the wide, large foot ring, it is thought that this is also a mukozuke. In addition, most of the famous Shōzu tea bowls are adaptations of mukozuke, and must originally have been kutsugata mukozuke, and the yakata and hishiguchi yakata tea bowls, which are so popular in the world of tea utensils, are clearly mukozuke. In any case, it is certain that this type of Shourui tea bowl is far removed from the spirit of the wabi-cha of the Momoyama period, and it is probably true that there were no orders for them as tea bowls. It is thought that this is because, from the Genroku period onwards, the tea ceremony in the Edo period became a style that strongly sought out the new and the different, and the idea of using Shourui tea bowls as tea bowls came about.

Gosu

In Japan, a type of crude red-glazed ware known as “Gosu-akae” was produced in large quantities in Fujian and Guangdong provinces at the end of the Ming and beginning of the Qing dynasties as a trade good, and was exported in large quantities to India and Persia from various regions of Southeast Asia, as well as to Japan. The rough white porcelain, which was yellowish-white or grayish-white in color, was decorated with free and unrestrained overglaze designs in red, blue and green, and its broken, interesting appearance was widely welcomed, as it evoked a sense of familiarity. In particular, the well-proportioned bowls and incense containers were considered ideal for use in tea ceremonies, and were much appreciated by tea masters. As well as the above-mentioned Kosometsuke and Shousui, there are also a series of blue and white porcelain wares, such as blue-glazed, indigo-glazed, white-glazed, mochibana-te, and blue-and-white porcelain, which are similar to this Kosometsuke. In the world of tea, the term “Gosu” (also written as “Goshu”) refers specifically to this type of blue and white porcelain. It is likely that the tea utensils were ordered from a local pottery because of the charm of their carefree simplicity.

Among these blue and white tea utensils, the water jar and tea bowl are particularly well known. The most famous of these is the water jar called “Hishima”, which has a horse design on the side and a landscape design on the lid, with clouds and mountains. Water jars with twelve-sided landscapes and oval-shaped landscapes are also highly prized, and the tea bowls with landscapes and round dragons are also popular. The painting is different from the thick brush strokes of the general underglaze blue and white porcelain, and is all based on the unchanging line drawing of Hifu. The white porcelain glaze, which has a faint grayish yellow tinge, is decorated with impressive depictions of jagged mountains, clouds, and pine trees in fine blue-black lines, giving the piece a profound literary flavor. This type of underglaze blue is particularly notable for its use in landscape paintings.

The place of origin of the blue and white porcelain is said to be Wuzhou, which is now the Wenzhou region of Zhejiang Province, because the name “Wuzhou” is often written as “Goshu” in Japanese. It is also said to be from the southern part of Fujian Province, either Shitan or Tanzhou, or from the Dehua kilns, which are famous for their white porcelain. There is also a theory that it is from Xizhou, in the northeast of Guangdong Province.

The name Swatou Ware (Shantou Ware) for the blue and red porcelain produced in Europe is thought to have come from the fact that it was shipped from Shantou in Guangdong Province, and it is thought that, just as with Imari ware, the name may have come from the fact that the ware was actually produced in the remote region of Shantou. The theory that it was made using stones seems to be the most likely, but there is no conclusive evidence for either theory. In any case, looking at the wares known as “Gosu-te”, it seems that the kilns that produced them were not limited to a single location, and that in fact, similar wares were produced in various places.

Annam

Tie-dyeing underglaze blue

The history of Korean ceramics is a good example of how successive waves of Chinese ceramics influenced the Korean peninsula and led to the development of a brilliant history of Korean ceramics. The history of ceramics in Annam, or present-day Vietnam, also dates back to the Han dynasty, but the subsequent changes have generally followed the trends in mainland China. In the past, there were white porcelain and celadon in the Tang and Song styles, followed by white porcelain with black floral patterns, and there were already examples of Yuan and early Ming-style blue and white porcelain. There are a number of examples of this type of early blue and white porcelain that have been passed down in Japan, such as the twin-eared vases with cloud and dragon patterns, which are said to have been part of the imperial collection of the Ryūei Emperor, and which are very much in the Yuan style. The blue and white porcelain produced by the Annam tie-dyeing method, known as Beni-Annan in the world of Japanese tea ceremony, is thought to have been produced between the 15th and 17th centuries, and is thought to have been introduced to Japan between the Momoyama and early Edo periods. Compared to Chinese ceramics, Annam ceramics are said to be generally less strongly expressive and complex in technique, and to have a gentle, southern feel and a somewhat feminine quality, perhaps due to the difference in ethnic climate. However, the tie-dyeing technique known as “Shibori-te” that was admired by tea masters has a hint of the early Ming style, and its open-hearted charm is unique even among An-nan blue-and-white porcelain. Judging from the style of the painting, it is not from the end of the Ming Dynasty. Shiborite is a technique in which the blue pigment oozes and flows in the glaze, creating a mottled effect. This is thought to be due to the weak quality of the glaze. In the literature, in the “Banpo Zensho” from around the Genroku era,

Annam: The blue and white porcelain is of poor quality and the designs are crude. The same applies to the foreign porcelain of Nanjing and Wuzhou. There is a distinction between old and new. There are many types of imported porcelain, but they are not considered valuable. The old types are considered valuable. There are many types of imported porcelain, but they are not considered valuable. The old types are considered valuable. There are many types of imported porcelain, but they are not considered valuable. The old types are considered valuable. There are many types of imported porcelain, but they are not considered valuable. The old types are considered valuable. There are many types of imported porcelain, but they are not considered valuable. The old types are considered valuable. There are many types of imported porcelain, but they are not considered valuable. The old types are considered valuable. There are many types of imported porcelain, but they are not considered valuable. The old types are considered valuable. There are many types of imported porcelain, but they are not considered valuable. The old types are considered

The Kan’ei Nohakagami says that Anan blue and white tea bowls are different from those made in the Wu Zhou style. The price is one gold coin.

Shibori-te: high-quality goods. Tea bowls, incense burners, blue and white patterns, etc.

Shibori-te, Sometsuke, also shown in the right tea bowl section. Sometsuke is a high-quality item. There are also tea bowls, cylindrical tea bowls, etc. Shibori-te is a term used to refer to items that are named according to the period in which they were made, depending on the scenery, etc.

However, it is known that shibori-te tea bowls are high-quality items made using the Sometsuke technique.

There are quite a few famous examples of shiborite teacups that have been handed down in Japan. The most famous examples include the Fujita family’s Unryu-mon Hana-buki (flower vase), the Owari Tokugawa family’s Unryu-mon O-hana-buki (large flower vase), and the Senke family’s Tokei-buki (vase in the shape of a Buddhist statue). In the case of water jars, the water jars that have been handed down from the temple Katsurashun-in, a sub-temple of Myoshin-ji, and the water jars that have been handed down from the Fujimura Yoken tea ceremony master are particularly noteworthy. There are relatively many tea bowls, and among them, the so-called dragonfly-patterned tea bowls, which have large dragonfly designs, are the most highly prized, and are representative of the dragonfly-patterned tea bowls. The blue pigment seeps into the glaze, scattering in thick and thin patterns, and the clumsy dragonflies, which are drawn in broad strokes, crumble further, creating a truly mysterious pattern. The tea master who selected this unusual tea bowl certainly had an eye for it. There are also various other patterns, such as arabesque, flowers and birds, and flying phoenixes, but when it comes to tea bowls, dragonfly paintings still stand out above the rest.

It is not yet known exactly when and where these shibori ware were made.

Generally speaking, it is thought that they were made at the end of the Ming Dynasty and the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, during the Momoyama period and the early Edo period, but this is based on the assumption that they were brought to Japan during the early Edo period. There seems to be a distinction between old and new in the shibori technique, but the older style is similar to the Ming style, and it is thought that it dates back to at least the second half of the 15th century. However, if you look closely, the dragonfly design has a slightly different shape to the other arabesque patterns, so it is thought that it is slightly later than the others. In addition, the kilns where the underglaze blue was fired were famous for the Yue kilns in the capital of Bac Trang Annam, near Hanoi, and there is a theory that the tie-dyeing technique in particular may have originated in Yue. There are also several other places, but all the specific facts are unknown.

Beni Anan

Alongside the shibori-te, the Beni Anan red-glazed tea bowls are also highly prized. Very few of these bowls are still in existence today, and apart from two bowls in the Tokugawa Art Museum collection, which were passed down through the Owari Tokugawa family, and two or three bowls that have been passed down through old families in Aichi Prefecture, there are only a couple of bowls from Indonesia. However, bowls and plates of the Annan redware have been brought back from Indonesia from time to time in recent years, and by looking at these, we can get a rough idea of what they were like. All of them have a unique shape characteristic of Annam, and the rims of the bowls are slightly turned up at the edge, with the particularly high and large foot rings being particularly noticeable. The inside of the foot ring is always covered with a brownish-red glaze. The clay is made from fine greyish-white clay, and the white glaze is slightly yellowish, with fine cracks visible. The red painting is mainly a simple arabesque pattern, and is more lively than the old red painting of the Ming dynasty, but it is also rougher, and is much more archaic than the underglaze red painting. Even when used together with underglaze blue, the underglaze blue is extremely restrained. In flat bowls, you can also see high-quality pieces that are decorated with gold. These pieces are probably from the 15th or 16th century.