Shigaraki ware is produced in Shigaraki Town, Koka County, Shiga Prefecture. It is one of the oldest pottery kilns in Japan, along with the neighboring Iga Marubashira Kiln in Mie Prefecture.

The pottery industry in this area was probably founded around the time of the Tenpyo period (757-65), as evidenced by tile fragments found in the ruins of the Ourano Mausoleum Shrine in Shigaraki Town, and extended from Nagano to Unoi, Obara, Asamiya, Tarao and other villages. This is called Koshigaraki. In the Muromachi period (1333-1570), the tea ceremony finally began to flourish, and Shigaraki products were made by Takeno Shaowaku, who was deeply in love with Shigaraki products and had a type of tea utensil made in the Tenmon and Eiroku periods (153-1170). Rikyu, the successor to Shao-o, also gave designs to Shigaraki potters and had them produce Shigaraki ware. This is called Rikyu Shigaraki. From the period of the rise of the tea ceremony in the Tensho era (1573-192) to the Kan’ei era (1624-44), Rikyu’s grandson Sotan had tea utensils made in the style of his grandfather. This was called Sotan Shigaraki. In the same period, Enshu Shigaraki was made under the direction of Kobori Enshu, followed by Hon’ami Aerial Nonomura Ninsei, Arirai Shinpei, and others who used their own techniques to produce various types of Shigaraki ware using the clay of Shigaraki. They are called “Kora Shigaraki,” “Ninsei Shigaraki,” “Shinbei Shigaraki,” and so on. During the Genna and Kan’ei periods (1615-44), they also produced so-called “Shingen pots” (tea pots with a white waist and white ears) at the order of the Tokugawa Shogunate. During the Kansei era (1789-1801), Hokusai (Hokuonsai), a tea master from Osaka, favored Shigaraki. During the same period, a craftsman from Owari (Aichi Prefecture) came to Japan and introduced a type of glaze called hagi-nagashi, which was presented to the imperial court and the Tokugawa shogunate. This was followed by TANII Naokata of Nagano and TAKAHASHI Shunsai of Kamiyama, who became renowned as good craftsmen. After the Bunka-Bunsei Era (1804-30), the products were exclusively practical and crude articles such as tea pots, oil cups, heating bottles, tea bowls, oil fingers, Buddhist altar utensils, hibachi, suribachi, teapots, earthenware bottles, rice bowls, gyohira, and kataguchis. Since the beginning of the Meiji period, the manufacture of indigo pots, itochiri pots, toilet bowls, sulfuric acid bottles, and crucibles has flourished in particular.

The relationship and distinction between Iga and Shigaraki ware is difficult to distinguish because of their geographical and historical relationship. In terms of their historical relationship, they share the same period of origin, and since they are located in close proximity, they experienced the same historical changes during the Genpei and Sengoku periods. In particular, when Oda Nobuo conquered Iga during the Tensho period (1573-192), all the potters in the area moved to Shigaraki, and whenever some incident occurred, they easily moved from Kou-mura to Otomura. Even after the Iga-Shigaraki area was settled by Takatora Todo, the two often quarreled over issues such as the location of a landfill. From a geographical point of view, the relationship between the two is complex and close. The two are located south and north of the border mountain range. The so-called Hakuchiyama lineage in Marubashira (Marubashira, Ayama-cho, Ayama-gun, Mie Prefecture), which could be called pure Iga, and the pure Shigaraki lineage in the Nagano to Ourano area (the distance between Marubashira and Nagano is 12 km) are clearly different and can be used as a clue to distinguish the products. (The distance between Marubashira and Nagano is 12 km). Therefore, the old Makiyama kiln in Iga is only about 100 meters away from the border to Shigaraki. Moreover, in Shigaraki, the Kamiyama kiln was built with clay from Mount Sango, so the materials used for both kilns were identical. The difficulties were as described above, but in terms of clay, glaze, and adze markings, the differences between the two are generally as follows. (1) Iga clay has a fine texture, while Shigaraki is coarse. (2) Iga soil contains large pebbles, while Shigaraki soil has smaller pebbles and more pebbles than Iga soil (with some exceptions). (3) Iga clay is tightly baked, and its reddish color is lightly red like cherry blossoms, while Shigaraki clay is reddish, similar to peach blossoms. (4) The white of Iga clay is pure white, while Shigaraki clay has a slight rat color at the bottom. (5) Iga clay is relatively heavy, while Shigaraki is relatively light. (VI) The blue glaze of Iga is transparent mauve or true blue beadloose, while the blue of Shigaraki has a blackish tea glaze on the bottom. Iga clogs are often simply glazed with blue from the mouth, while Shigaraki clogs are often glazed with a thin underglaze of melted yellow earth from the mouth. The so-called “geta” mark of Iga and “ashidate” mark of Shigaraki are derived from the unevenness of two cleats fitted into the potter’s wheel, and both originated in the same period. In Shigaraki, however, this type of geta seal has been seen less frequently since the rise of the tea ceremony in Iga, and is seen not only in old Shigaraki works but also in many later works that were made with geta marks with dentures or dentures just like kiln marks.

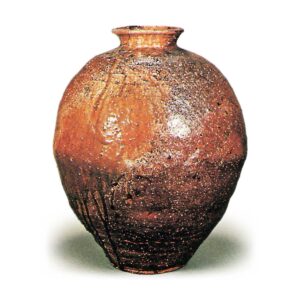

Shigaraki and Iga ceramics were originally made by farmers without much thought and thus suited the taste of wabicha (tea ceremony) masters. The tea ceremony utensils were often influenced by Kyoto and Seto, and some were imitations of local ceramics from other regions. The main types of tea utensils produced from the Koshigaraki period to the main kiln period are: seed pots, washcloths, ooto-buckets, travel pillows, tea urns, and senbe pots, as well as tea bowls, incense containers, flowers, and bowls. In terms of production, the clay is heavy and hard. It is mixed with large and small feldspar grains. The miscellaneous clay types are fused together to form a firm and unequal clay body, giving it the appearance of a rock. It burns and shrinks violently and unevenly in the kiln, and its shape is more irregular than the original form, with piles and kilns forming easily. Some clay has a rich luster due to the adhesion of firewood on the surface of the clay. The color of the clay is generally reddish brown, and those with high iron content have a particularly strong brown tone. When feldspar is molten, milky white patches appear. (2) The reason why the clay is rough and contains sand and gravel is because, unlike the general method, no water straining or other treatment is performed, but rather the fine powder is sifted through a large sieve. Therefore, it is used for making piled strings or hand-kneaded products, but it is not suitable for the potter’s wheel. Therefore, it was later made on the potter’s wheel using sifted clay, and its form was more refined than that of sifted clay.

(3) Glaze: Originally, earthenware was not glazed, but when fired several times at high heat, wood ashes were deposited on the surface of the molten clay and a glaze film was naturally formed. Therefore, the colors are not consistent, and include light yellow, light green, yellow, dark brown, and dark green. In later periods, however, glazes were used. In other words, glassy beadlo glazes were used. This is an ash glaze that tends to be greenish in color and is intended for decorative purposes, and is often applied to vases, water jars, and other types of vessels. However, the inferior work is unpleasant because it reveals the intent of the artist’s work. The pieces that have fallen in time are covered with a milky white glaze with a strong luster in addition to the beadlo glaze, and the reddish color of the clay and the charring from the kiln fire intermingle to create a scenic effect.

Some pieces were fired while collapsed, causing the glass glaze to flow in the opposite direction, so-called “upside-down glaze. The ash-filled areas are sometimes charred, creating a “burnt” appearance that is appreciated by tea masters. (4) Production: There are only a few of these vases made in the old days, as they were made while farming. The mouths of these vases were usually somewhat receptive, and the ones with double-layered mouths and strong mouths were old. As time goes by, some of them are not double-layered and the mouth structure becomes weaker. However, those with a thicker body and wider mouth and slightly raised edges are the oldest type. Those with a rounded, twisted back mouth structure are from the Muromachi period (1333-1573) and later, while those from the Edo period (1603-1868) are less kindly twisted back. There are various shapes of vases, and the stone wash vases were used as hanging flower vases by early tea masters. Those with holes drilled before firing date back to the Edo period. Tea pots and senbe pots began to appear after the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1600), and some of them are numbered. The oldest ones have a pattern of power on the shoulder.

Those with arrow-shaped designs are slightly later. The footprints on the bottom of the clogs are dentures, and the older they are, the more indistinct they are. Those with distinct dentures and dentures are of later date.

In addition to the clog marks, there are some with bamboo screen-like marks and pressed grass leaf marks. These marks may have been made during the drying process before firing. Older pieces are generally not sufficiently hardened. The oldest ones are nearly unglazed, and the mixed feldspar in the clay is not fully dissolved, resulting in stone haze and small cracks running in three directions. The smallest pots, large pots, tea pots, and senbe pots, all of which are used for small vessels and purveyors, are strongly fired.

Tea caddies of the Iga and Shigaraki periods can be tentatively classified as semi-porcelain-like ceramics made of rough clay mixed with feldspar and fired without glaze in the same way as in the early private kiln period, or as the above-mentioned ceramics with bead glaze.

The most appreciated features by Wabi-tea masters since ancient times have been the sturdy appearance, the reddish-brown color of the clay, the beadlo glaze, and the burnt appearance. The most pleasing features to Wabicha people since ancient times have been its sturdy appearance, red-hot clay, beadlo glaze, and charring.

Shigaraki ware was appreciated as tea utensils during the rise of tea ceremonies at the end of the Muromachi period (1336-1573), when its vases and jars were loved for their wild taste, and Shigaraki ware came to be used exclusively as tea utensils. The tea ceremony tableware was also used as a water jar. From the end of the Muromachi period to the Azuchi-Momoyama period, tea pots occupied a major position as tea utensils, comparable to tea containers and tea bowls, and Shigaraki tea pots are mentioned in tea books as being highly prized. Tea bowls, incense containers, kensui (tea bowls), and tea bowl covers were also highly prized, and tea masters had Shigaraki ware designed and produced locally in Shigaraki, or had the clay from Shigaraki ware fired in Kyoto and other cities. However, while the early Shao-Shigaraki and Rikyu-Shigaraki tea utensils still exist today, the characteristics of some of the later Shigaraki wares, such as Sotan-Shigaraki, Enshu-Shigaraki, Hanging Shigaraki, Ninsei-Shigaraki, and Shinbei-Shigaraki, are not clear and are quite ambiguous.

(1) Shaozu Shigaraki clay is reddish brown in color and at first glance could be mistaken for Ibe ware. (1) Shigaraki clay of the Shaozu period is reddish brown and could be mistaken for Ibe ware at first glance. A note says, “The clay of the Shao-ogaku period has a blackish tinge, and the yellowish medicine is staining the clay. (2) In a letter from Rikyu Shigaraki, it is written, “Shigaraki of Soyoshi, also called Shigaraki of Rikyu, is modeled after Shigaraki of Soyoshi, in which the clay is white with a light brownish-red color and the yellowish medicine has a bluish tinge. (3) Sotan Shigaraki is not described in detail. (4) Made of Enshu Shigaraki clay, it is thin and elaborate. Some of them resemble Hagi or Karatsu. (5) The tea bowl with the inscription “Hakuunzan” in the collection of the Owari Tokugawa family is said to be a Shigaraki bowl in the air. (6) The left side of the Nisei Shigaraki bowl is inscribed “Nisei”. There is also a piece called “Nikiyo-Mujirushi,” but it was not made by Nikiyo.

(7) Shinbei Shigaraki: There have been different theories since ancient times that the inscription Shin is by Shinjiro of Iga, or that the Shigaraki Shinbei is a tea caddy in the style of Lu-Song and is unmarked.