A ceramic tea or water heater. It has a body with a spout and two ears, and a lid. As a rule, handles are made of other materials. The term “dobin” was probably coined after 1887 (Meiji 20) for earthenware bottles made of porcelain as well. Until then, all earthenware bottles were made of ceramic. There have always been Imari-sometsuke (blue and white porcelain) earthenware bottles with porcelain handles, but these were all used for pouring sake, not for making tea. It is not clear when the word “earthenware bottle” originated. The earthenware bottles found in “Heiji Monogatari” are sake bottles. The word “earthenware bottle” appears in the “Heiji Monogatari,” but the word “tea kettle” appears in the “Meimono Rokucho” and “Sho Kotogijikou Setsuyoshu,” so it is likely that the earthenware bottle we use today appeared during the Genroku and Shotoku periods (1688-1716). The oldest known example is a black-glazed earthenware jar from the kiln site at Kuromuta, Kijima County, Hizen Province (Kuromuta, Takeo City, Saga Prefecture), which had already been closed down by the Genroku period. It was probably first made in Kitakyushu after the Bunroku era (1592-4). No illustrations of earthenware bottles can be found in “Hunmong zuishiki” and “Wakan sansai zukai,” and they first appear in “Hunmong zuishiki taisei” published in 1789.

The use of earthenware bottles probably began in the early Edo period, spread somewhat in the middle of the Edo period, and reached its peak at the end of the Edo period. In other regions, it is usually called “dobin,” but in Ibaraki, Yamaguchi, Shimane, and Shikoku prefectures, it is called “dohin. The dobin was not first invented as a tea container, but probably originated as an infusion, and later came to be used as a tea jar. From its form and use, it can be concluded that the earthenware jar was a transplant from the iron kettle, pouring vessel, or medicine can. The body of the earthenware can be roughly divided into two types: the hi- celadon porcelain hana-katou round type and the zhang type. The Zhang type is usually called “Arithmetic grain shape,” and in Mashiko, it is called “ship shape. This type was inherited from the shape of tetsubin (iron kettles) and other types of vases. Both types have existed in Mashiko since ancient times, but the older ones have fewer round ones and the later ones have more round ones. Most of the remaining yakudobin are of the shape of a tablet.

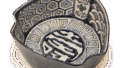

The body is usually divided into front and back, with the front facing the customer (i.e., the spout is on the right) since it is used with the right hand. Most of the older pieces have a flat bottom, while the hemispherical raised bottom seems to be a later invention. The hemispherical raised bottom seems to have been invented later. There is one with three simple legs around the bottom, which seems to have been made to resemble armor, etc. Later, it remained only as a formality, but has finally disappeared. There are two types of spout: a straight spout and a curved spout. There is a hole for holding tea dregs at the point where the body leads to the spout. Sake pourers do not have this hole. There are almost three types of ears, the oldest of which are square, large, and beautiful, clearly indicating that they were made by goldsmiths. This is not found except on very early pieces. The next type is Yamagata, which in Mashiko is called Nukiyama. Most of them were made by die-cutting. As shown in the figure, there is a single mountain, but there are also three mountains, again following the metalworking method. By the end of the Edo period, all earthenware kettles had a rounded edge except for the rectangular ones. The most recent origin is a simple twisted clay ear, probably dating from the Meiji period (1868-1912) or later. As a rule, only this type of ear is marked with a black dot on the top and three lines at the end of the spout. There are various types of lids, but those made until the early Meiji period were generally divided into three types: yama-buta (mountain lid), hira-buta (flat lid), and otoshi-buta (drop lid). Figure 1 shows a mountain lid, which is mountain-shaped and supported by the rim of the mouth, with a knob in the center. It is one of the oldest styles, and one of its characteristics is that the knob has degenerated and remains almost only as a formality, serving no actual purpose, and when removed, it is held by the rim of the lid. The lid is flat, and is often found on small earthenware bottles. The lid is usually very high at the mouth rim and sinks down, the lid is also concave inward, and the height of the knob is lower than the mouth rim. This is because the nature of the cheap earthenware bottles necessitated stacking them, and they were fired on top of each other with the lids still in place. Therefore, the ratio of the mouth to the whole is large. Shigaraki Mashiko produced many of this type of earthenware, which is commonly referred to as uchiki-dobin. The train earthenware jar is of the Minato type. The oldest earthenware bottles are unglazed, and are still found in Nabamushi earthenware bottles in Yamaguchi Prefecture and Yaku earthenware bottles in Tottori Prefecture. The next oldest type, based on excavated earthenware, is black-glazed, which can change its color to tenmoku, kaki (persimmon), or ame (candy) depending on the amount of heat and the glaze mixture. In Kitakyushu and Seto, this type of ware was widely produced. Today, the most representative examples are from Hita, Oita Prefecture. Other types of pottery include those with a normal glaze, those with a white glaze, those with a sea squirt glaze, and those with a green glaze. The green glaze is relatively common, especially in Soma, Shigaraki, Akashi, and Kitakyushu. The glaze is applied about four-fifths of the way up, but not on the bottom and rarely on the interior, possibly because unglazed wares are more resistant to fire. In Shigaraki and Akashi, the fine vertical lines are called “tochiri,” while horizontal lines are called “itome. There are various types of painting, such as tetsue-e (iron painting), ai-e (indigo painting), and shibori (tie-dyeing). The patterns include landscapes, flowers, plants, and many others. Some paintings are covered all over. There are also window paintings painted on the rounded surface of white paintings. There are so many earthenware potteries in various regions that it is impossible to count them all, but Shigaraki, Akashi, and Mashiko are the most abundant. However, earthenware pots declined temporarily due to the emergence of enameled ware and aluminum. The above is based on the theory of Yanagi Muneyoshi. Since earthenware bottles have long been neglected as miscellaneous vessels, there are no other references to earthenware bottles other than the 10th issue of the magazine “Egei” (Elements of Art).

Dobin (earthenware teapot)

Dictionary

Dictionary