Master craftsman Eiraku Hozen in Kyoto. Adopted son of Zengoro Ryozen X, he succeeded to the 11th generation of the Nishimura family. He was first named Zengoro, then Zenichiro, and later took the family name Eiraku. The name Eiraku was derived from the Eiraku seal, a gift of the Kishu Tokugawa family.

He was born in 1795 (Kansei 7, 1785, Tenmei 5) as the son of Sawai Sokai in Kyoto, and became a Buddhist disciple of Koumeiin of Daitokuji Temple due to circumstances at an early age. However, due to his natural inclination to玩, he was not able to practice sutra chanting, and finally left the priesthood after being introduced by the monk Osuna, and became the adopted son of Nishimura Ryozen, a master of earthenware furnaces among the ten Senke schools, who had no children. At the age of 11 or 12, he had already mastered ordinary ceramic techniques, and at 14 or 15, he began training with Ichiemon, a dollmaker on the Fushimi Highway, where his talents were finally demonstrated. At the same time, he mastered the Matsunami school of calligraphy, studied painting under Eitake Kano, waka poetry under Kagetsune Kagawa, Zen under the monk Otuna, and the art of secret study under the doctors Shingu Ryotei, Hino Kinsai, Ando Keishu, Hirose Genkyo, and others. He sought the friendship of those in Tokyo who were skilled in one art and one skill, and developed their skills. In 1827, Tokugawa Chiho of Kishu heard of his fame and opened a kiln in Nishihama Palace, where he fired exclusively kojiki copies and other porcelains, which he labeled “Kairakuen-made. Chiho praised his conservation skills and awarded him a two-character Eiraku silver seal and a four-character gold seal of the Kawahama branch (with two characters of Seien added on the back). In Kyoto, he received special treatment from the Konoe and Takaji families, and was especially honored by the Takaji family with a three-character “To Tsuriken” seal. In addition, he was invited to the Koto Pottery of the Hikone Clan (Hikone City, Shiga Prefecture) and the Jakugaya Kiln of the Zesho Clan (Otsu City, Shiga Prefecture), where he demonstrated his skills, and was commissioned to build a new kiln by Nagai of Takatsuki (Takatsuki City, Osaka Prefecture). The Mitsui family, for example, opened their treasured vessels to the public, and the family head, Mitsui Takanari (Makiyama), often collaborated with them in producing vessels. In this way, the ceramic skills of the conservationists finally reached their peak, and they were able to produce imitations of Chinese, Korean, and Annamese wares, including underglaze blue, gold brocade, copy of kojiki, and celadon, as well as celadon, with extremely brilliant purple, yellow, red, blue, and green glaze colors, and their fame was so great that they became the sole focus of Asano’s favor. Not content with this, he devoted himself to the study of the HUNKAN style reddish-purple colored glaze (cinnabar glaze), and devoted himself to its achievement, giving up all of his resources. This was the reason why he invited Takano Nagahide, who was despised by the shogunate at the time, to his house, and his enthusiasm was so great that he hardly ever took care of his family affairs. In 1849, the family system had to be reformed under the leadership of Takebe Ryoyu and others. In other words, he handed over the family governor to his son Kazuan, who left home and went into hiding, suffering the tragic fate of being exiled in all four directions. In the following year, he set out for Edo on a certain day in November of the same year, planning to open a kiln in Edo by relying on the Marquis of Zensho Honda. However, his plan did not go as planned, and he returned to the west in May 1851.

At this time, there was a man named Koizumi Yoshimine, a samurai of Enmanin in Otsu, Omi Province (Shiga Prefecture), who deeply regretted the loss of Kenpo and invited Kenpo to Otsu, planning to manufacture pottery as an official kiln of Enmanin. In other words, he built a new kiln and opened it for the first time in the winter of the same year. This is known as Konan ware. He devoted all of his mature ceramic skills to this kiln and operated it for four years, but in the late summer of 1854 (Kaei 7), he developed an ulcer in his back and finally died on September 18 of the same year, at the age of 60. He died on September 18 of the same year at the age of 60. He had two sons, Kazu Zen and Sozaburo Nishimura (Kaizen).

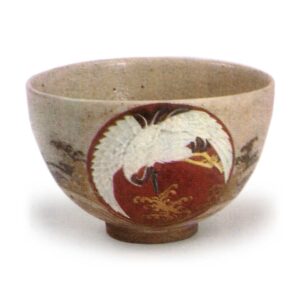

His works were extremely multifaceted, ranging from gold brocade, Shozui, Gosu, and Kogi three-color porcelain to all major imported ceramics such as Manryaku red glaze, Nanban Yakishime, Unkaku, and Mishima. He was especially good at copying Shozui, and was also famous for copying Kairakuen ware. Furthermore, his gold brocade was so skillful that it was called “Eiraku Kinrande,” and his son Wazen also strove to imitate it. The variety of pottery produced by the Yongraku family covered a wide range of items, from tea utensils to everyday items such as fire pans, plates, bowls, small bowls, earthenware bottles, sake cups, and even decorative items such as flower vases, incense burners, and ornaments. Among tea utensils, there are tea bowls, water jars, kensui, and kabutsuki for powdered green tea, as well as kyusu, tea bowls, and cool furnaces for sencha (roasted green tea). This diversity of production is a characteristic of conservation and an expression of flexible skills. In this respect, he is in a similar vein to Niami Dohachi, but while Dohachi had a background in carving and used a spatula as his specialty, Konsen had no such background and used a paint brush exclusively to achieve the desired effect. In addition, he imitated many Chinese products and tried to outdo them, inscribing his own name “Dai Nihon Eiraku Zou,” which is said to be a continuation of Ninsei’s Japanese taste. The inscriptions on the pieces are numerous, as shown above. Among them, the two-character silver seal of Eiraku, a gift of the Kishu family, was shared with his adoptive father Ryozen according to the wishes of the Lord Chiho. The inscription “以陶 ‘世鳴'” is from a calligraphy brush given to him by Prince Chikahito Arisugawa, the king of calligraphy in a single piece before his departure for Edo in the fall of 1850 (Kaei 3), and he used it for all products other than those for sale after he established the Honan kiln.