As already mentioned, ash-glazed ceramics are high-fired glazed ceramics made from plant ashes that were fired in Aichi Prefecture and other areas in the Tokai region from the late Nara to Heian periods. It goes without saying that ash-glazed ceramics have their origin in Chinese ceramics, just as colored-glazed ceramics did. In China, ash-glazed ceramics using plant ash as a glaze were already produced in the Shang dynasty. Although the origin of this glaze is not yet known, it was probably inspired by the natural glaze produced as the firing temperature increased for the rather hard ash ceramics that were being fired widely at that time. Although the process of subsequent development is not clear, from the end of the Later Han to the Three Kingdoms period, it developed in Zhejiang Province in the south and became Koyue porcelain, and by the Sui and Tang periods, it had developed into magnificent celadon and white porcelain. In contrast, in Korea and Japan, hard pottery such as Silla ware, Baekje ceramics, and Sue ware: which were derived from Chinese ash ceramics, were produced, but although naturally glazed wares were produced on rare occasions, the technique of consciously developing them into ash glazed wares did not exist until the 8th century.

As far as we know, the production of ash-glazed ceramics began in Japan in the group of ancient kiln sites at the southwest foot of Sanageyama in the eastern hills of Nagoya. This indicates that production had already begun around 760. This was probably inspired by Chinese ceramics imported through the government trade at that time. However, ash-glazed ceramics were not fired everywhere where Sue ware was produced. It began at the Sanage kiln and spread to northern Owari, then to Mino, and finally to Ise Yamashiro in the En’e area during the Heian period (794-1185), but the main production area never left the Tokai region. The reason for this is that the kilns were restricted by advanced production techniques and suitable raw material clay. The most important factor that enabled the Sanage kiln to produce ash-glazed ceramics was that the clay that could withstand such high temperatures was not Pleistocene clay like Sue ware: but Neogene clay, which is closer to the host rock, and was abundant in the hilly area 20 km square in the eastern part of Nagoya City. This was the most important factor that made it possible to produce ash-glazed pottery at the Sanage kiln.

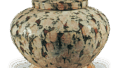

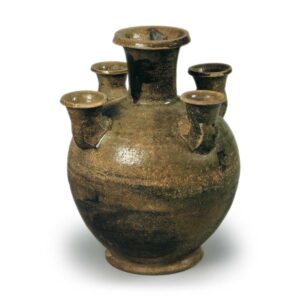

The variety of ash-glazed pottery vessels is extremely rich, including various daily vessels and ritual vessels that are descended from Sue ware from the Kofun period, as well as various types of Buddhist vessels and tableware that were newly added to the pottery. However, not all of these vessels were uniformly ash-glazed, and the application of glaze varied from period to period. In the Nara period, glazing first began on vases, most commonly on flat vases and long-necked vases that changed from the narrow-necked vases of the Kofun period. In the Heian period (794-1185), there were hand-formed jars and water jars in the form of tokuri, which were copied from Chinese celadon water jars. There is a wide variety of jars, the most representative of which is a short-necked jar of the same shape as the Shosoin medicine jar, and from the mid-Heian period onward, there are wide-mouthed jars and spittoon jars that imitate Chinese celadon. The appearance of full-scale brush-painted ash-glazed bowls and plates dates from the 9th century, and is attributed to the influence of Chinese ceramics. The most common type is a set of two bowls, one large and one small, and there are also gilt-bronze gun arms with ridges at the waist. In addition to commonly used plates with a low base, there are also dishes with a stepped interior or exterior surface and a ridge at the waist, such as those from Kurozasa Kiln No. 7 in Togo Town, Aichi County, Aichi Prefecture, which are thought to correspond to the “tsingko” type of dishes mentioned in the Engi-Shiki (Engishiki). Special types of plates were also produced. In addition to the above, the Sanage and Onohoku kilns produced many hand-glazed bottles, bowls, and plates decorated with inlaid floral motifs and floral rings in imitation of Chinese ceramics, but these were not, in principle, ash-glazed. As a rule, these were used as the base for green-glazed ceramics.

How then were ash-glazed ceramics produced?

As mentioned earlier, the distribution of kiln sites indicates that the Sanage kiln used high quality pottery clay with high fire resistance from the east. In particular, the concentration of production sites in the Kurozasa district in the eastern part of the region from the latter half of the 9th century onward may have been due to the demand for high-quality white clay to produce more effective color tones in ash glaze. Some of these wares have such fine, high-quality clay that they appear to have been watered, especially those with inlaid flower-and-bird patterns. In terms of the molding of vessels, the late 8th century, when primitive ash-glazed ceramics were produced, saw the emergence of vertical vessels such as bottles and the improvement of potter’s wheel technology. It is thought that the wheel-thrown water-grinding method of grinding a large number of vessels from a single lump of clay came to be adopted. From the end of the 8th century to the 9th century, the two-stage jointing technique, in which a plate is not inserted between the body and the mouth and neck of the vessel, but directly connects the head and body, came to be used.

At the same time, the water-grinding technique was adopted for large vases and other large objects, and wheel-throwing techniques improved dramatically. This is probably due to the direct transmission of the technique from China, as well as the firing technique described below. The kilns used for firing ash-glazed ceramics were similar to those used for Sue ware: with grooves dug into the hillside and walls and ceilings covered with clay mixed with tinned grass, in a long, narrow, semicircular structure. In the early stages of Sue ware: the slope of the kiln floor was gentle at around 15 degrees, which was suitable for smoked reduction firing, but the slope gradually changed to a steeper angle, especially at the Sanage kiln, where the angle was as steep as 30 to 40 degrees from the late 8th century to the early 9th century, In particular, the angle of inclination of the Sanage kilns changed to a steep angle of 30 to 40 degrees from the end of the 8th century to the beginning of the 9th century. This change in kiln structure was caused by full-scale reduction firing, and was suitable for high-temperature firing of ash-glazed ceramics. In addition, the kiln tools used for firing the new ash-glazed bowls and dishes, such as tocings, tsukkas, and potter’s wheels, are identical to those used in Chinese ceramics from the Tang dynasty to the Five Dynasties, which indicates the spread of production techniques.

Finally, let us discuss some of the changes in the production of ash-glazed ceramics. Although ash glaze ceramics were of much lower quality than Chinese ceramics, they were not widely used in the early days as high-end ceramics second only to imported ceramics. In Aichi Prefecture, where it was produced, ash glazed wares were sometimes found at the remains of villages, but from the end of the Nara period to the beginning of the Heian period, the main target of supply and demand was limited to the central Kinai region, such as the imperial court offices and large temples. In the 9th century, with the introduction of new production techniques from China, bowls and plates began to be fired, and glazed objects were expanded to include many types of vessels, such as vessels and jars, and the range of supply and demand rapidly expanded, with items being transported from the Tohoku region to the Chugoku region. As demand increased, ash-glazed ceramics gradually began to be produced from northern Owari to Mino as well. In particular, from the 10th to the 11th century, with the rise of farming villages due to the development of agricultural technology, the range of supply and demand for ash-glazed ceramics became even wider and denser. Recent excavation results show that since the latter half of the 10th century, there has been a nationwide increase in the number of pottery excavated from village sites in Ipan. Ash-glazed ceramics are no longer the exclusive preserve of the upper classes. In response to the spread of ash-glazed ceramics, there has been an expansion of production sites and a shift in production methods. Aside from some of the best pieces, second-class bowls and plates were mass-produced by firing 12 or 13 pieces directly on top of each other, without using saggars or totins. Glazing methods also changed accordingly, and a simplified method of applying glaze only around the perimeter of the vessel was adopted in order to avoid losses due to over-firing. Furthermore, the increase in demand led to the expansion of production areas, and by the 11th century, the production areas ranged from the Tokai region to parts of the Kinki region, including Omi Yamashiro. This trend inevitably led to a decline in quality. By this time, ash-glazed ceramics had been transformed into daily vessels for the general public. The background to this was the massive importation of Chinese ceramics through the Japan-Song trade, which was changing the supply-demand relationship for the upper classes. Toward the end of the 11th century, ash-glazed pottery kilns in the Tokai region abandoned glazing altogether and shifted to the production of mountain tea bowls as everyday utensils for peasants by changing to a mass-production kiln system with a dividing column inside the kiln.