Kiseto is one of the oldest ceramics produced at Seto kilns, and is covered with a soft pale yellow glaze that is moist and stagnant. According to “Kogei Shiryo,” “Koseto was invented by a certain Fujishiro II, who began applying yellow glaze to pottery, and produced pale yellow glazed tea pots, incense burners, vases, tea bowls, etc. at the Seto kilns. This is why it is called Ki-Seto, and has been produced successively ever since. However, the “Kogei Shiryo” theory is not found in any of the aforementioned descriptions, and is probably based on an article in the “Chawaniki Bengokushu” that states, “There is a Koyakute on an ancient tea container in Manchu. The glaze on the Chunshan Frog Voice tea caddy, a famous item from the Manchu Kiln and Chung Hsing Kiln, is yellow glazed, but it is not what is known today as yellow Seto. There is of course a distinction between yellow glazed and yellow-seto wares. Yellow glaze is a pale yellowish-green coloration of iron due to oxidized iron firing, which is a common occurrence in Seto wares in ancient times. Ki-Seto is a more recent style, in which the condition of the traditional yellow glaze technique was consciously studied to obtain this coloration, and the color is not as uncertain as that of yellow glaze technique. In other words, yellow glaze hand is a precursor to the development of yellow glaze, but it is not yellow glaze itself. The term tsubaki-kiln hand Yellow Seto, which is commonly used to refer to yellow glaze hand, is merely a term of convenience. Kizeto is a technology of the semi-colonial period in terms of the development of the kiln style. In the “Chawan Chawan Handbook”, “Wakan Meihiki Kohan”, “Meiriso”, “Chawan Meimono Zushiki”, etc., Hakuan tea bowls are referred to as Koseto. However, in the one owned by Sotani Hakuan, which is said to be the original Hakuan bowl, Kobori Enshu simply wrote on the box, “Seto, Hakuan Tea Bowl,” and it is not marked as Ki-Seto or Shin-Naka-Ko. It is difficult to determine whether or not Hakuan itself is from Seto, but the theory that it is from Hakuan Ki-Seto is highly unjustified. The “Chawan Chajiri-Merisho” says, “Ki-Seto, Owari Seto ware of the later period, has a ground color of hiwa, a mixture of hiwi and yaku, and a variety of shapes, such as cylindrical, flat, and cedar, as seen in the clay around the base. This theory is most plausible, and as mentioned above, Kizeto was produced during the semi-arid kiln period (the same period as Shino ware), i.e., around the time of Rikyu and Oribe. The name “Kizeto” may also date from the time of Rikyu, as it is found in various tea ceremony books. In addition, Kiyoho 9 (1724), 11 (1726), and 18 (1733) in the Keiki, Kiyoho 9 (1724), 11 (1726), and 18 (1733), Kiyo Seto inokuchi, hana vase, and tea bowls can be found.

There are three types of Kizeto ware: guinomimi handles, iris handles, and chrysanthemum dish handles. Technically speaking, however, the thicker guinomi-te were placed near the fire floor where they were exposed to high heat, while the thinner ayame-te were sometimes placed at the back of the kiln to avoid high heat and fired at the same time, as the gall volatilizes and the color tends to fade away. The distinction between the two periods does not necessarily go back and forth. Rikyu preferred the light and dry style as seen in Chojiro’s tea bowls, while Oribe went one step further and aimed for a change in design. In Kizeto, the relatively simple guinomi-te (cup with a small cup) is considered to be Rikyu’s preference, while the iris hand, which sought design effects by adding vitriol, is considered to have come from Oribe’s preference. The Koseto masterpieces include a tea bowl inscribed Asahina, a flower vase with a standing drum owned by Rikyu, and a large wakizashi (a large bowl with a large handle) owned by Rikyu.

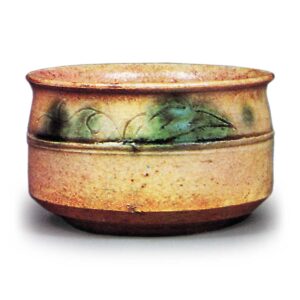

This Ki-Seto ware is thicker and has a relatively shiny glaze, so-called “beadlo skin. The glaze is thick and has a relatively shiny beadlo skin, and where the glaze has flowed thickly, there are many cases of sea squirt glaze appearing. There is no vitriol in this hand. There are more types of vessels than yellow glazed wares, and the shapes are more varied. These include incense burners, lotus flower-shaped bowls, and plates with inka designs and comb patterns. Kilns that fired this type of pottery include the Asahi Kiln in Seto, the kiln under the kiln at Ohgaya, Kani County, Mino Prefecture (Kani Town, Kani County, Gifu Prefecture), or Gonoki, Ena County (Sogi-cho, Toki City). Some people call this hand Ki-Seto with Hakuan handles because it resembles the glaze of Hakuan [Ayame hand] Ayame hand refers to the same type of Ki-Seto as the rimmed bowl with the Ayame design in the Inoue family’s old collection. It is thinly made and has what is called an aburage-buji (deep-fried skin). It has a simple and elegant underglaze design of iris with unrestrained iron-brown and copper-green flecks, and has a burn mark on the base of the bowl. The piece has all the promises of the tea masters, and is like no other.

This is the same type of Kiseto ware as the small chrysanthemum-shaped dishes excavated in great numbers from the Ohira and Kasahara kilns in Mino and the Shinano kiln in Owari (Aichi Prefecture). It has a very high luster, with fine intrusions and a clear yellow color. The rim is covered with a bright copper-green rim, which flows down and interlaces with the yellowish green, creating a showy beauty. All are thickly made, and are mostly used for everyday utensils. The body of the kataguchi is lavishly covered with copper-green glaze, while the soy sauce pouring vessel and the jar have copper-green glaze on the shoulders. This was fired in a kiln that had lost its leader, and to the untrained eye that did not appreciate the serene and elegant beauty of Ayame’s work, it probably looked even more beautiful this way. This technique has been continued for a long time, and even today, traces of it can still be seen in suribachi and other items. As for the kiln sites where Takeya Kiseto was fired, excellent examples of guinomi-te and ayame-te have been excavated at three kilns (the Shita, Muta-do, and Naka kilns) in Aza-Okaya, Kani-machi, Kani County, Gifu Prefecture; the Yuiemon kiln in Aza-Ohira, Gifu Prefecture; and the Motoyashiki kiln in Kusiri, Izumi-cho, Toki-shi, Toki Prefecture.