Echizen and Suzu are two prominent ceramics representing medieval pottery in the Hokuriku region. As is well known, Echizen is an unglazed pottery produced in the mountainous region from Echizen City to Niu County in southern Fukui Prefecture. It is often confused with Tokoname, as Echizen pottery is mainly made of jars and pots with a natural green glaze on a brown surface that is reminiscent of Tokoname. Suzu ware, which has been known since the 1945s, is pottery produced in the hilly area around Suzu City at the tip of the Noto Peninsula. At first glance, it appears to be a type of Sue ware: with its blackened surface, and is made mainly of jars, pots, and mortar and pans.

These two types of pottery are representative of the Ji ware and Sue ware types of the three categories of medieval pottery described in Volume III, “Seto Mino. Again, I would like to briefly describe the classification of the two types of medieval ceramics, namely, the Ji ware type and the Sue ware type. The medieval ceramics of the Ji ware lineage are derived from the ash-glazed ceramics (Shirashi) produced in the Tokai region during the Heian period, and include (1) ash-glazed and iron-glazed ceramics such as those from Seto and Mino, (2) unglazed tableware for daily use only, such as those from the Yamachawan kilns in the Tokai region, and (3) unglazed jars, pots, and mortars, such as those from Tokoname and Atsumi, which were mainly three types of pottery. (4) In regions that did not have a tradition of ash-glazed ceramics during the Heian period (794-1185), the techniques of the Sanage and Tokoname kilns were introduced at the time of the shift to medieval ceramics, and three main types of ceramics were fired: jars, pots, and ground bowls. The Echizen and Kaga ceramics treated in this volume belong to this fourth group. The Sue ware type consists of two types of ceramics: (1) Bizen ceramics, which inherited the tradition of Heian-period Sue ware but changed to brownish-brown ceramics fired by oxidizing fire during the Kamakura period (1185-1333), and (2) grayish-black ceramics fired by reducing fire, which are called “Sue ware” ceramics, and inherited the same production techniques as Sue ware. The pottery of Suzu, Kameyama, and other areas covered in this volume belongs to the second type of Sue ware.

The fourth type of japanned ware belongs to the Echizen and Kaga kilns described below, as well as the Sasagami kiln in Niigata Prefecture and the Iizaka Oto kiln in Fukushima Prefecture, and the various kilns in Miyagi Prefecture, distributed in the Hokuriku and Tohoku regions. Of these kilns, Echizen, Kaga, and Iizaka are described in a separate section, so I will omit their explanations, but I would like to summarize and explain some of the other kilns that have become known in recent years. Sasagami is located in Wolfsawa, Agano City, Niigata Prefecture, and has three known medieval kilns. Sixteen other Sue ware kilns are known in the area between Sasagami and Toyoura villages, and there is no evidence of ash-glazed pottery firing. The investigation of old kilns in this area has been continued since 1968 by Professor Shigeo Nakagawa of the Faculty of Letters, Rikkyo University, and especially in 1973, two medieval kilns in Wolfsawa were excavated and their contents were revealed (“Investigation of Wolfsawa Kiln Group,” Report I, 1973, by the Archaeological Laboratory, Faculty of Letters, Rikkyo University). According to the report, both of the two old kiln sites show the same kiln structure as that of the Tokai kilns, with a dividing pillar at the border between the firing chamber and combustion chamber. The jars and pots are very similar to those of Tokoname in both form and molding technique, and in particular, the technique of adding a stepped pattern to the joints of the wheel-stacking molding is a direct import from Tokoname and different from Echizen and Kaga wares. The fact that they also produced bowls and plates is another characteristic of Tokoname.

Next, we will discuss three kilns in Miyagi Prefecture among the Tohoku kilns.

One of them is the Tōhoku Kiln located in the Aza Tōhoku, Shirakawa Inu Sotoba, Shiraishi City, in the southern part of the prefecture.

The existence of this kiln has been known since around 1947, but it was not until 1973 that it began to attract attention as a medieval kiln in the Tohoku region. The old kiln sites are divided into three groups, and although the existence of 20 kilns has been confirmed, the structure of the kilns is not yet known because they have not been excavated. The current group is the Izunuma Kiln, which includes the Shinanoura Kiln in Nitta, Sasako-cho, Tome City, and the Kumagariyama Tsukazawa Higashisawa Kiln in Tsukidate Town, which became well known after 1966. Currently, the existence of fifty-two old kiln sites has been confirmed. The kiln structure is similar to that of the Tokoname Echizen kilns, which are of the celadon ware type. The last one is the Sanbongi Kiln in Takata, Osaki City, which was discovered in 1975. The above three kilns became known in detail through the “Medieval Pottery of the Tohoku Region” exhibition held at the Tohoku History Museum in 1983. All three kilns produced only three types of ceramics: jars, pots, and mortars, all of which have brownish-brown surfaces due to oxidized firing.

Although there are differences in details such as the mouth rims, they are morphologically similar to those of Ko-Joname, and are considered to be in the fourth category of the 瓷器 series.

It is considered to be in the fourth category of the japanned ware series. Another group of old kiln sites that has been attracting attention in recent years is the Odo Kiln in Aizu Wakamatsu City, Fukushima Prefecture. This is the largest group of ancient kiln sites in the Tohoku region, with 208 kilns ranging from Sue ware kilns of the Nara period to medieval kilns of the early Muromachi period. Of these, 36 are medieval kilns, but excavations that have been underway since fiscal 1988 have revealed that they are mainly of the Ji ware type.

Next, I will discuss medieval ceramics that belong to the second category of the Sue ware series. The best known examples of this type of pottery are Suzu ware in eastern Japan and Kameyama ware in Okayama Prefecture in western Japan, but recently it has become known that ceramic production sites are expanding throughout the country. The contents of each are discussed in detail in a separate section, but this Sue ware type II is distributed throughout the country except in the Tokai region, and in some cases (e.g., Bizen and Kameyama) it is in close proximity to the Jiyu ware type IV and Sue ware type I, and is not necessarily unified as a single type of pottery by type of production. The Sue ware is not necessarily unified into a single type of pottery by type of proc. The Suzu kiln is the only pottery in the second category of the Sue ware series that has been excavated to date, and although it has not yet reached the stage of generalization, the types of products are mainly limited to three types: jars, pots, and mortars. Even when bowls are produced, as in the case of the Suzu kiln, it is only in the early stages of production.

The medieval ceramics discussed in this volume mainly belong to the Sue ware type, and even if they belong to the jar type, they are limited to kiln sites that did not have a tradition of glazing techniques in the previous period. All of these types of ceramics are mainly miscellaneous daily wares with a strong peasant coloration. However, not all of these ceramic production areas followed a uniform development process.

The conditions of origin, the process of development, and the history of decline and extinction varied according to the conditions of each region. Looking through the ceramic production areas, we can recognize two major types. The first type is the kilns that have continued to be produced continuously until today, and the second type is the ones that disappeared after the middle of the Muromachi period (1333-1573). The first category includes Echizen and Kaga, but Kaga turned to porcelain production in the early modern period and differs from Echizen, Bizen, and Tanba in aspect. On the other hand, those belonging to the second category include kilns in Suzu, Kameyama, Iizaka, Oto, Sasagami, and Miyagi Prefecture. Why did such a difference in the date of operation occur in different regions, even though the main products were equally miscellaneous daily wares? For example, in the case of Suzu, as shown by the outer container of a sutra case (dated Nin’an 2) excavated from the sutra mound behind Oiwa Nisseki-ji Temple in Toyama Prefecture, medieval pottery had already begun to be used in the late Heian period. In addition, the distribution of the products was surprisingly wide, and from the late Kamakura period to the early Muromachi period, they were transported from various places along the Sea of Japan coast to Hokkaido, where they competed with Echizen in the trade area. In addition, Iizaka Oto is located in the remote Tohoku region, while Kameyama is located in Bicchu bordering Bizen, and this cannot necessarily be attributed to the backwardness of the region.

This phenomenon is also seen in Tokoname, Atsumi, and Nakatsugawa in the Tokai region, and is thought to be due in part to the different fuel economies resulting from the nature of the pottery clay. One of the reasons for this is thought to be the difference in fuel economy due to the nature of the clay. It is thought to be the result of economic competition between the first type of Sue ware: which switched to oxide firing to meet increasing demand from the late Kamakura to early Muromachi periods, and the second type, which followed the reduction firing method. The second problem is the regional differences between eastern and western Japan. Of the ceramic production areas that have continued to the present day, in western Japan, Shigaraki and Tanba have inherited the production techniques of the jushi ware type, while Bizen has inherited the production techniques of Sue ware and converted to the medieval ceramic industry. In contrast, many of the kilns in eastern Japan, especially those in the Hokuriku and Tohoku regions, have converted to medieval ceramics by introducing the production techniques of the Sanage, Tokoname, and other ceramic ware types from the Tokai region. Those that follow the Sue ware system, such as those in Suzu, are limited to the Sea of Japan side of the Tohoku region.

This volume omits pottery from the Kanto region that is considered to be of the Sue ware type II, namely the Kamei Kiln in Saitama Prefecture, the Kanai Kiln in Gunma Prefecture, and other pottery distributed in Ibaraki and Chiba Prefectures, due to insufficient research.

Echizen Kaga

The Echizen Kogama, the largest medieval kiln in Hokuriku, became known to the general public surprisingly recently, after World War II. In the twenty-odd years since then, thanks to the efforts of Kyuemon Mizuno, who is almost the only researcher in the region, the Echizen Kogama has finally come to be understood in its entirety.

The Echizen kilns are located in the southern part of Fukui Prefecture, centering on Byodo, Echizen-cho, Niu-gun, and Kumagai, Miyazaki-mura, Niu-gun, and are distributed in groups on the southern slopes of each hill derived from the eastern foot of Joyama (elevation 513 m), which has a steep slope on the Echizen coast. The eastern hills are the distribution area of Sue ware kilns, and are clearly distinguished from the western hills of the Tenno River, which flows northward through the center of the Niu Mountains, turns eastward at Oda Town, and flows into the Nanketsu Basin. However, in recent years, a number of Ko-Echizen kilns, which are thought to date back to the end of the Heian period, have been discovered in the Kosohara area of Miyazaki Village, and it is now known that the Echizen kilns originated in the area where the Sue ware kiln sites are distributed. Apart from these, the main part of the site is located in the western hills, and seven groups of kilns are known from the south: the Sobara/Masutani, Kumagaya, Ogumagaya, Byodo/Ogamaya, Yakiyama, Oda, and Yamanaka kilns. Among these kilns, those with particularly large numbers of kilns include 17 Okugamaidani kilns and 15 Kamigahira kilns in the Kumagaya kilns, and more than 10 Kamidaishidani East kilns and 15 West kilns in the Byodo-Ogamaya kilns (see distribution map on page 87).

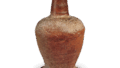

-The products of the Echizen kilns are mostly limited to three types of vessels: jars, pots, and ground bowls, with a few incidental items such as fishing tackle such as pottery weights. The jars come in a variety of sizes and shapes, especially medium-sized jars of around 25 cm in height, with a wide mouth, narrow neck, short neck, and no neck (Figs. 21-25). The shape of the rim is not uniform, with some having a rounded or beveled mouth, others being folded outward, and still others standing up in an “N” shape. Some of the large jars exceed 60 cm in height, and are characterized by either a thick body with a narrow neck or a rather wide mouth. Many of the latter have two or four forge-shaped ears on the shoulders. Small jars are around 20 cm high, with a short beveled neck and partially folded mouth rim to form a one-lobed mouth, or 10 cm to 12 cm high, with biconvex ears on the shoulder. There are two types of jars: those with a height of around 30 cm and large jars with a height of over 60 cm. The mouth rims of both types of jars have an “N” shape, which is very similar to that of Tokoname jars, but they do not have a broad rim band like Tokoname jars. This is probably due to the difference in the clay used. Suribachi also resemble Tokoname in exterior form, but differ in that the interior surface is decorated with a comb-like pattern of orogee during the Muromachi period (1333-1573). In addition, water jars (Fig. 59) were also produced on rare occasions. In western Japan, tea ceramics were produced in the late Muromachi period, but no examples have been found in Echizen kilns.

The clay used in the Ko-Echizen kilns is a sandy clay with a higher refractoriness and slightly higher iron content than that of the Sue ware kilns in the eastern area (Pleistocene), because the kilns are located in the Neogene stratum based on granite. It should be said that this clay was selected to be suitable for cold regions. In the molding of the jars, a circular base plate was first made on the potter’s wheel, on which clay strings were rolled up, and then the surface of the vessel was adjusted by using the first and second potter’s wheels. Some have geta markings on the bottom. A large jar is made in five or six steps by rolling up a wide clay cord on the bottom plate, allowing it to dry, and then adding more clay cords, similar to the process used in Tokoname, but without the continuous stamping on the joints at each step as in Tokoname. The surface of the vessel is adjusted with wood. As a rule, Ko-Echizen jars and mortar vessels are characterized by the application of one or two normally painted kiln marks on the shoulders. In the late Kamakura period, some of these pots and suribachi also have a comb-painting pattern. In principle, Ko-Echizen ceramics were unglazed, but ash glaze was applied in the early period, and in the late Muromachi period, iron glaze was applied by brushing over the surface of the ware. In the late Muromachi period, however, the use of rice field clay gave many of the vessels a blackish-brown color.

As indicated by the kiln structure, the firing techniques used in Ko-Echizen are thought to have been adapted from those used in Tokoname, while abandoning traditional techniques. The kiln structures known from excavations include two kilns, Kami-daishidani Higashi Kiln No. 8 in Oda-machi Byodo dug by the author in 1965 and Okugama in Miyazaki-mura Okudo dug by Mizuno in 1973, as well as Kaminagasa and Mizukami kilns in the 1975’s. The Kami-daishidani Higashi kiln is 15.5 m long, and the latter is approximately 18 m long. It is a large kiln, 15.5 meters long, and the latter is approximately 18 meters long, and is the type of kiln used in the Tokai region in the porcelain ware style, with a dividing pillar at the border between the combustion chamber and the firing chamber. Since there was no production of japanned ware in this area in the previous period, but only Sue ware: it is thought that the production techniques of Tokoname were introduced when the area was converted to medieval pottery production. In particular, the early use of ash glaze, the use of slightly reducing neutral glaze until around the middle of the Kamakura period, and the use of oxidized glaze from the latter part of the Kamakura period are consistent with Tokoname.

The location and date of the Echizen kiln have been unclear for a long time, due to a sutra jar excavated from a sutra mound at Anyo-ji Temple, Echizen City, but based on the contents of the Kozohara Kaminagasa ancient kiln site group excavated by the authors last year, the kiln is within the distribution area of Sue ware kilns, and the age of the kiln, based on the measurement of its thermal residual magnetic orientation The age of the kiln, based on thermal remanent magnetic azimuth measurements, indicates that it was converted from a Sue ware kiln to a medieval Echizen kiln in the latter half of the 12th century, or the end of the Heian period.

The medieval Echizen kilns can be chronologically divided into six stages: I. Late Heian – early Kamakura, II. mid Kamakura, III. late Kamakura – Nanbokucho, IV. early Muromachi, V. mid Muromachi, and VI. late Muromachi (see chronological chart on page 108). Although I have to omit the details of these transitions due to the number of pages, I would be happy if you refer to “The Development of Handicrafts, Ceramics, and Hokuriku in the Ancient and Medieval Periods” (“Japanese Archaeology”, Historical Period, Kawade Shobo Shinsha edition). The trade area of Echizen kilns is surprisingly wide, extending west to northern Kyoto, south to the mountains of Ibi-gun in Gifu Prefecture, and north through sea routes to as far away as the Hakodate area in Hokkaido.

Kaga is a ceramic region that has suddenly emerged in the last few years, and the name is probably still unfamiliar to the general public. The production of medieval ceramics in southern Ishikawa Prefecture was first noted in 1940 by the late Sataro Matsumoto in his book “Hon Kutani,” which included Gomado-yaki and Kushi-yaki, but research on the subject did not progress until after World War II. It was the investigation of Kiln No. 1 in Futatsunashi Town and Kiln No. 1 in Natani Town in Komatsu City conducted by Mr. Yoichi Ueno and others in 1969 during the construction of the Kaga Fuyo Country that clarified the position of Kaga Kogama as a medieval pottery kiln through the excavation of kiln bodies. This investigation revealed that the kiln structure was similar to that of Tokoname and Echizen kilns, with a column dividing the firing chamber from the firing chamber, and that the products were mainly jars and mortars similar to those of Tokoname (Yoichi Ueno, “Kaga Koto I, Kaga Medieval Ceramics,” Kanazawa University Institute of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, Japan, Report No. 5, 1973). Later, in 1973, in conjunction with the second phase of the above-mentioned country work, a survey of the two ancient kilns in Daitennodani, Nadani Town, and a survey of the distribution of the entire area finally enabled us to grasp the outlines of the Kaga Kogama.

The distribution area of the Kaga Kogama kilns is a low hilly area at an elevation of around 50 m, located between Awazu-cho, Komatsu-shi and Matsuyama-cho, Kaga-shi, facing the Shibayama Lagoon. These hills were the production site of Sue ware from the late Kofun period onward, and the early modern Matsuyama kiln was operated at the southern end of the hills. The Kaga kilns of the Middle Ages were distributed in groups on the slope facing a small valley on the south side of this hill, and about 30 kiln sites are known, including Okudani, Nadani Ootenno Valley, Kotenno Valley, and Kamiya subgroups. These old kilns include those from various periods from the end of the Heian period (Naya Kiln No. 1) through the Kamakura period (Daitennodani Kiln) to the Muromachi period (Kamiya Kiln), and it is estimated that the kilns were moved to Sakumi in Kaga City to the west during the Momoyama period (1573-1573). In the early Edo period (1603-1867), the Sukezaka Kiln across the Daishoji River to the southwest developed into the Kutani Kiln, while the ceramic industry in the area continued to produce porcelain on a small scale. Research on the Kaga kilns has only just begun. However, using fine-grained, high-quality clay, they produced Tokoname-style jars and pots, Echizen-style mortar and pans, and water bottles, and their mouth molding was rather similar to that of Seto, and they produced better-quality ceramics than Echizen. The pottery has only been excavated from a few sites, including the Komatsu Karumi Medieval Cemetery and the Nagataki Sutra Mound in Tatsunokuchi Town, Nomi County, so we will have to wait for further research to get a full picture.

Suzu

Suzu ware, which looks so black that it could be mistaken for Sue ware: was fired in the hilly area around Suzu City at the northeastern tip of the Noto Peninsula. It was not until the late 1960s that Suzu ware, which was often confused with Sue ware: came to be recognized as an important pottery representing a type of medieval pottery. In the comprehensive survey of Noto conducted by the Nine Societies in 1952 and 1953, it was reported that pottery of the Sue ware lineage had been produced until around the Ashikaga period, and in 1959, the Nishihoji kiln from the Muromachi period was designated as a Sue ware kiln and a cultural property of Suzu City. It was during a comprehensive survey of Noto sponsored by Hokkoku Shimbun in 1963 that Suzu ware was clearly positioned as a medieval kiln.

The number of old kiln sites discovered for Suzu ware, which is widely distributed from the Sea of Japan coast north of Hokuriku to the Tohoku region and southern Hokkaido, is small in comparison with the large amount of pottery excavated. Currently, the number of known old kiln sites is 16 in 10 locations over an area of 26 km from north to south and 3 km from east to west, but most of them are concentrated within a 5 km area from north to south and 2 km from east to west in Ueto-cho and Hodate-cho, Suzu City. However, the number of sites found in this rare distribution area is expected to increase in the future. Let us start from the north,

One kiln at Maguintoge Kiln, Suzu City

One kurobatake kiln at Teraya, Misaki-cho, Suzu City

Two Kamewarizaka Kilns, Ueto-cho, Suzu City

Three Kilns, Kasugano Houjyuji Kiln, Hodate Town

Nishihouji Kiln, Hodate Town, the same: two units

One Gyonobu Kiln, Noto-cho, Hozu-gun

Ohata Kiln, Hodate Town

One kiln, Kashihara-go Kiln, Hodate Town

Two units, Toriyao Kiln, Hodate Town, Kashiharago Kiln, Hodate Town, Kashiharago

Two Hiyama Kilns, Ohya Kiln, Misaki Town

As shown above, the distribution of kilns extends from Uchinoura to Ootoura, and all of them were built on hills slightly away from the coast. The oldest kiln, the Kamewarizaka Kiln, is located at an elevation of more than 200 meters above sea level.

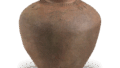

As with other medieval kilns, the products of the Suzu Koyo are mainly three types of miscellaneous wares: jars, vases, and ground bowls, but in the early period, bowls, plates, and bottles were also fired.

The most common types of wares are jars and ground bowls. There are two types of jars: large jars over 70 cm tall and small ones around 35 cm tall, but the latter are by far the most common. Both types of jars are characterized by the striated patterning on the surface of the vessel. Some of them have been polished to remove the tapping. These examples faithfully preserve the tradition of Sue ware jars. The shoulders are characterized by painted or stamped designs. There are two types of jars, large and small, with or without knapping on the surface. Large jars (30-50 cm high) are four-lobed, with distinctive ears that are flared at both ends.

Small jars are about 20 cm tall and have a short neck and mouth, and often have comb patterns on the shoulder and body. Rarely, there are four-mimi jars with Kosedo-style horizontal ears and twin-mimi jars with ring-shaped vertical ears on a round body. Suribachi are shallow, large flat bowls common to medieval kilns, but in the case of Suzu, they do not have a base from the beginning. Since the middle of the Kamakura period, the inner surface has been grated by combing. In addition to the above three types of vessels, a few thicker, coarser bowls and plates were also produced in the early period. Another characteristic of the Suzu kiln that is not found in other Sue ware medieval kilns is the pottery of vases, such as vases, jars, and bottles.

First, the clay is coarse and more refractory than Sue ware: and is often interbedded with pebbles. The cross sections after firing show that most of them have a porous and coarse texture. In the molding process, the bottom of the jar is first made to a certain height on the potter’s wheel, and then clay is added to the base by winding up the clay strings. The bottom of the vessel is made of two types: one is made by ita-okoshi (a technique in which the clay cord is rolled up and then joined together) and the other is made by static itokiri (a technique in which the clay cord is cut with a wooden plank). The vessel surface is struck using a mold with engraved patterns, so there are striations on the surface. Some of the early vessels have a blue ocean wave pattern on the inner surface, which clearly shows the connection with Sue ware. All of these vessels are marked on the shoulder with a kama seal or an impressed seal. The larger vases were made by winding up the strings and adjusting the surfaces with a jar. Many of the small jars are wheel-thrown. The bottoms of these vessels are made by both ita-okoshi (shaping the bottom of the vessel) and shizukuri (cutting the bottom of the vessel with a wooden plate). Suribachi are made by winding up a cord, and the edges of the mouth are chamfered from the beginning.

The firing process is clearly the same as that used for Sue ware: but excavation of the kiln site has only been conducted for two kilns, the Saifo-ji and Ho-jumi-ji kilns, and the kiln structure has not been fully elucidated. The Kamakura period Hōjūji Kiln No. 3, excavated in July 1972, is a larger version of a Sue ware kiln, with a total length of more than 9 m, a firing chamber width of 2.6 m, and a maximum firing chamber width of 3.6 m. The floor inclination was 26 degrees. The Saifo-ji kiln of the Muromachi period has a total length of 12 m, a width of 3.2 m, a height to the ceiling of 1.1 m, and an inclination of 28 degrees. It is therefore wider and has a lower ceiling than the Sue ware kiln. The firing method is almost the same as that of Sue ware.

So when and where did Suzu ware originate? Although there is a remarkable continuity with Sue ware in terms of products, there are no Sue ware kilns within the distribution area of the Suzu kiln. The closest kiln site is the Shuei Kiln Site Group in Wajima City, about 30 km to the southwest. In the case of the Suzu Kiln, the kiln was moved to a larger area when it was converted to a medieval kiln, and the hilly area near Uchinoura, which is convenient for marine transportation, was probably chosen for the kiln, in addition to the problem of ceramic clay. The oldest known Suzu ware is a jar and mortar excavated from the Sutra Mound at the back of Oiwa Nisshakuji Temple in Kamiichi-machi, Nakashinagawa County, Toyama Prefecture, which were used as the outer container for a sutra cylinder inscribed in the 2nd year of Nin’an (1167). It is known that this kiln was already established as a medieval kiln in the late Heian period. The author divides the period from the mid-12th century to the first half of the 16th century into five major phases, based on changes in the form, combination, and design of each type of ware. The first period (12th century, late Heian period) is the period of the beginning of the pottery industry, which, like other medieval kilns in various regions, mainly consisted of jars, pots, and mortar, but also retained some offerings, and fired religious objects and Chinese copies of objects. The first period includes the above-mentioned Nisseki-ji Sutra Mound and the Kamewari-zaka Kiln. Many of the jars and pots are thin and fine, with fine diagonal lines in the beaten pattern and few kiln marks. Jars with Tomoe patterns are rare examples. A jar from the Kamewari-zaka kiln with a large comb-shaped wavy pattern was produced, but it is a copy of a brown-glazed jar from South China. Small quantities of bowls and plates were also fired during this period, in addition to vases, jars, and other special wares. In Period II (13th century, pre-middle Kamakura period), jars and pots were still carefully molded, and many of them were relatively fine. Four-mimi jars and vases were fired. It was during this period that the inner surfaces of mortar and pestle began to be grated with a comb-like texture. Many of the kiln marks on the shoulders are still painted on at this stage. Period III (14th century, late Kamakura and Nanbokucho periods) was the peak of Suzu ware. Vessels were mostly limited to jars, pots, and mortar, and vases, bowls, and plates were no longer produced. The tapping patterns became coarse stripes, and the vessel surfaces became polyhedral as they were beaten vertically, and the tapping patterns changed to a twilled cedar shape in response. Many four-lobed jars were produced with ears that were peculiar to Suzu, and the comb pattern on the shoulder and body of the jars is also characteristic of this period. Kiln marks of circles and chrysanthemum flowers can also be seen in many cases. During this period, Suzu ware reached its largest commercial scale and was transported as far as Hokkaido. In the IVth period (15th century, pre-mid Muromachi period), the Suzu kiln entered a period of decline, with a decrease in the number of types of wares and a noticeable trend toward formalization. Most of the jars were polyhedral in shape, and the tapping patterns were applied in the form of twilled cedar. The mouth rims of large jars were made of jade. In general, the neck of the jars tended to be smaller. The grating on the inner surface of the mortar became denser, and the upper surface of the broadened rim band became decorated with comb-patterns.

In the Vth type (16th century, late Muromachi period), production was limited to a few suribachi and other types, but was eventually forced to cease before the prosperity of the Echizen kilns.

Five-ring pagoda inscribed in Eikyo 3, in the cemetery of Meisenji Temple, commonly known as Kamakura Yashiki, Anamizu Town

Iizaka Kameyama

Blackened pottery excavated from ancient and medieval sutra mounds and ruins in the Tohoku region used to be all treated as Sue ware. However, over the past decade or so, as the reality of Suzu ware has become better known, the term “Suzu ware” has been applied to these items. While many of the wares excavated from the Sea of Japan coast to Hokkaido are indeed Suzu ware, there are many wares excavated from inland areas to the Pacific coast that are slightly different in terms of the base firing process. In particular, the unearthing of blackened pottery shards from the ruins of Taga Castle and the excavation site of the Tohoku Longitudinal Expressway has been attracting attention for the past two or three years, and investigations have been conducted in various areas in search of the production sites of these wares. As a result, the Inu Sotoba Kiln, located approximately 4 km east of Shiroishi City, Miyagi Prefecture, and the Iizaka Kiln in Fukushima City were discovered. The Shiroishi Inu Sotoba Kiln was constructed with several kilns in parallel at two points on the southwestern hillside of the Inu Sotoba community, and the excavated pottery shards include large, pale brown jars. The pottery pieces excavated include a large, light brown jar. Clearly, the oxide-fired pieces are different from those from Suzu, and are more along the lines of Tokoname pottery. In contrast, one of the two groups of old kiln sites at the Iizaka Kiln in Fukushima City is similar to Shiroishi, but the other group is darker and more similar to Suzu. The Iizaka kiln was excavated by the Fukushima City Board of Education in 1963 and 1967 as a Sue ware kiln.

However, the shiny black pots and jars found at the Tagajo castle site and in Miyagi Prefecture are different from those of the Shiraishi Iizaka kilns, and the remains of these kilns have not yet been discovered.

Let us discuss the Iizaka kiln. According to Mr. Masakazu Akiyama of the Fukushima City History Compilation Committee, two groups of Iizaka kiln sites are known today: the Bishamondaira and Akagawa kilns. The Akagawa kilns are located on a southern slope about 1 km south of Tennoji Temple of the Myoshinji sect of the Rinzai Sect, 3 km west of the Iizaka Onsen, and two kilns are known.

The one on the east side is said to have been destroyed around 1953 due to land reclamation. The one on the west side was excavated by the Fukushima City Board of Education in March 1963.

The kiln had already lost its mouth and part of its smoke outlet due to soil removal, and only a 6-m-long kiln body remained. The kiln body is about 1.8 m wide with a 25-degree slope on the floor, almost the same as that of a Sue ware kiln. The pottery shards excavated from the kiln were jars and pots, but they were a mixture of blackened and light-brown pottery, which indicates that the ceramics were from the late Kamakura period.

The Bishamonpei Kiln is located at an elevation of 300 m near the top of a hill from the Yuno mountain road community in Iizaka Town, north of the Iizaka Hot Springs. There are four kilns in a row, and the two kilns on the east side were excavated in 1967, and many pots, jars, and other ceramic shards were found. The kiln body is similar to that of the Akagawa kiln, but the slope of the floor is gentler. Judging from the excavated ceramics, this pottery belongs to the first half of the Kamakura period. The excavated ceramics are grayish black or blackish brown in color, similar to those of Suzu ware, and include jars, pots, and mortar and pans. The Jouan-mei cylinders and jars in the collection of Tennoji are probably products of the Bishamonpei kiln site group.

Thus, we can conclude that the Iizaka kiln was converted from a Sue ware kiln to a Sue ware-type medieval kiln in the late Heian period, and that it was shifted to oxidized firing around the late Kamakura period. However, the details of the actual situation should wait for future research. While the Suzu ware was made exclusively by smoked reduction firing, the Iizaka kiln, which was converted to oxidative firing in the middle of its development, cannot therefore be called a Suzu ware. This may indicate the difference between the Sea of Japan side and the Pacific side.

Next, I would like to discuss Kameyama ware from Okayama Prefecture, which is famous as a medieval kiln in western Japan with a strong Sue ware tradition. The knowledge of Kameyama ware dates back to 1930, when Mr. Iwataro Mizuhara gave the name “Kameyama style earthenware” to ceramics found at an old kiln site in the precincts of Jinzen Shrine in Yashima, Tamashima City, in the “Kibi Kouko” (Kibi Archaeology) No. 5. Later, in 1940, Mr. Setsuo Munezawa clarified that the kiln had fired miscellaneous vessels such as jars, pots, ground bowls, and pots from the Heian period to the Muromachi period (1333-1573). After the war, the distribution of kiln sites was further discussed by Nishikawa Hiroshi and Makabe Tadahiko and others, and the character of the kiln sites was also discussed based on the distribution of products, etc. In fiscal years 1984 and 1985, the Okayama Prefectural Board of Education conducted a preliminary survey in conjunction with the construction of the Sanyo Expressway and excavated related sites, including six old kiln sites, and some of their contents were revealed (“Okayama Prefecture, Okayama Prefecture, Okayama Prefecture”). The excavations revealed a part of the contents of the ruins (“Okayama Prefecture Excavation Report of Buried Cultural Properties 69,” 1988).

The remains of old kilns have been found concentrated in Kameyama, Yashima-aza, Tamashima City, and Sue, Kinko-cho, Asakuchi City, and are thought to have been established around the beginning of the Kamakura period, after a unique transition from Sue ware. The three main types of products are jars, pots, and mortar, and pots, shallow bowls, braziers, and roof tiles were also fired. Jars have a short neck and a spherical body, and the earliest types are wide-mouthed jars with a short neck and a mouth rim that turns outward. The bottom of the jar is large and flat, made of rolled clay cord and the surface of the vessel is shaped with coarse latticework. The earlier the jar, the larger the bore and base diameter, and the lower the firing temperature. After the end of the Kamakura period, the diameter became smaller and the bottom of the body became more rounded. The pounding patterns on the surface of the vessel became twilled and chamfered. The largest jar was about 65 cm in both height and body diameter. It was made by rolling up thick clay cords, and the vessel’s surface was beaten with a shaping tool with a grid pattern. The inside surface is adjusted with brushwork. The tip of the short neck was cut into a narrow, outward-tilted face. Later, the neck of the mouth became upright, and the rim band thickened into a slightly wider green band that tilted outward, and eventually transitioned to a wider band with a large droop. The flat-bottomed suribachi is a medieval type of large flat bowl with the rim band partially bent back to form a single mouthpiece, and has no base. Early examples were narrower, cut on a flat surface at the edge of the mouth, but gradually became wider and tended to tilt inward. In addition, a few dishes and other vessels are also found, but in smaller quantities.

The kiln in which these vessels were fired is not yet known, but they were made of low refractory Pleistocene clay, with low firing temperatures, and many of them are gray in color and of tile ware quality. Some of them are grayish-black, brown, or reddish-brown in color, but all of them are unevenly fired due to the low firing temperature.

The origin of Kameyama ware cannot be traced back to the Kamakura period. It was at its peak in the middle of the Kamakura period (1185-1333), when it was the most abundant in terms of quantity, and then rapidly declined toward the end of the Kamakura period. The distribution range of Kameyama Pottery extends from Okayama Prefecture to parts of Hiroshima and Yamaguchi Prefectures, with a high density of distribution mainly in the plains and coastal areas. In particular, large quantities have been excavated at the Kusado-Senken site in Fukuyama City, Hiroshima Prefecture, and the relationship between this pottery and Bizen ware and other pottery is well understood. Just as Suzu ware competed with Echizen ware for trade space and was abandoned by the middle of the Muromachi period, Kameyama ware is thought to have been in a competitive position with Bizen ware.

Traditionally, Kameyama ware has been compared to Suzu ware in eastern Japan in terms of medieval Sue ware in western Japan, but since the end of the 1965’s, the discovery and investigation of the East Banshi medieval kilns in Hyogo Prefecture, mainly the Kamide Uozumi kiln, has changed the picture significantly. The first of these to be noted was the Kamide Kiln in Tarumi Ward, Kobe City. Later, with the discovery of the Kamide Kiln, research progressed rapidly in the 1950s, and it became clear that similar Sue ware medieval kilns had developed widely along the Kako River from north to south. The Miki Kiln Site Group to the north and the Uozumi Kiln Site Group to the south are the largest Sue ware medieval kilns in western Japan in terms of production scale, and the Uozumi Kiln in Akashi City in particular is a large group of over 40 ancient kilns. In 1979, the Hyogo Prefectural Board of Education conducted an excavation survey, and it is known that the kilns were cellar kilns similar to Sue ware kilns, and that they fired mainly jars, pots, and mortar, as well as bowls and roof tiles. Among these kiln sites, the existence of smoke pipe kilns that produced only bowls by division of labor was also revealed (Hyogo Prefectural Board of Education, “Uozumi Old Kiln Site Group,” 1983).

On the other hand, in the Chugoku Mountains, the existence of the Katsumada kiln site group, consisting of more than 30 kilns, became known in Katsuo Town, Katsuta County, Okayama Prefecture, and excavations were conducted in 1978 to reveal the actual kiln site. The kiln structures are almost the same in scale and structure as ancient Sue ware kilns, and bowls, jars, pots, and mortar were fired in these kilns. In the Kinai region, pottery shards with knapping patterns similar to Sue ware have been found among the newly excavated items from the Heijo Palace site, while jars, mortar and tsubagama, pottery and tile ware have been found in fairly large quantities mixed with earthenware and tile ware at several sites, including the Miyata and Tsunoe sites in Takatsuki City, Osaka Prefecture. A fairly large number of pottery jars, suribachi, tsubagama, and kettles have been excavated from several sites in Takatsuki City, including the Miyata and Tsunoe sites. These jars vary in size from those with Sue ware-like latticework patterns on their surfaces to those with N-shaped mouth rims similar to those of the Tokoname ware. Many of the ground bowls are flat-bottomed and have wide, grated comb patterns on their inner surfaces. Fragments of a shiny black jar with a carbonized surface were also found at Butsudo-ji Temple in Sanda-machi, Iga City, Mie Prefecture. It is not clear where these miscellaneous vessels were fired, but since they are not thought to have been imported from far away, it must be assumed that production was continued by descendants of nearby Sue ware artisans.

In the San’in region, it has been pointed out that in Shimane Prefecture, in addition to imported items from Tokoname, Bizen, and Tanba, dark brown jars discovered in Sobutani, Hirose-cho, Yasugi City, and reddish brown coin pots and bowls discovered in Saginoura, Taisha-cho, Izumo City, may have been fired in the respective localities as miscellaneous ware (Tadashi Kondo, “Regional Characteristics of Ancient and Medieval Ceramics (6) San-in Archaeology of Japan, VI). Other medieval ceramics of unknown provenance include the jar from Hatsuyama, Ayabe City, Kyoto Prefecture, discussed in this volume, which bears an inscription from the first year of Gen’ei (1118) that serves as the outer container for a sutra tube.

As described above, it is considered rather common that areas where Sue ware was produced in ancient times continued to produce jars, pots, and mortars in the medieval period until the Muromachi period (1336-1573).