Sue ware is a type of earthenware produced in Japan between the 5th and 12th centuries. It is generally blue-gray in color, hard and tightly baked, and has little water absorption. The origin of this pottery can be traced back as far as the Shang Dynasty in China. The technique of ash ceramics continued to be passed down and developed throughout the vast area of China, and its products and techniques gradually spread to the surrounding regions. Eventually, the technique of ceramic earthenware was introduced to the Korean peninsula, and by the early 5th century at the latest, it is believed to have taken root mainly in Baekje. Soon after, the technique was introduced to Silla, giving birth to the so-called Silla ware, an offshoot of which reached our country and gave birth to Sue ware. Sue ware was thus established by following the technical lineage of ceramic earthenware developed on the Korean peninsula, but ceramic earthenware very similar to early Sue ware has also been found in the Nakdong River basin in Korea, which is closest to our country.

Sue ware was highly prized by tea masters during the Edo period (1603-1868) as a form of pottery for appreciation, and was often referred to as Gyoki ware or other names. Later, Kiuchi Ishitei named it kyokudama jar, but the name did not become common. In the Meiji period (1868-1912), Sue ware came to be called Iwai-bee (itsu, shuku-gon, sai-gon) or Korean earthenware, but around 1887 (Meiji 20), the name Shuku-bee earthenware came into use, and the name was finally fixed. In the Showa period (1926-1989), however, Goto Moriichi and others pointed out that “Shukubu” in Shukubu earthenware should be read as “Hafuribe,” and since Hafuribe refers to the people who are engaged in rituals, the name Shukubu earthenware is not correct. He also proposed to call Shukubu earthenware “Sue ware” by adopting the characters and words from “Kiki,” “Engishiki,” and “Wanamisho. On the other hand, Hamada Kosaku and others used the term “ceramic earthenware,” but this term did not become universal, and after World War II, the term “Sue ware” became common and has continued to be used today. The term “ceramic earthenware” is appropriate as a generic term for gray earthenware.

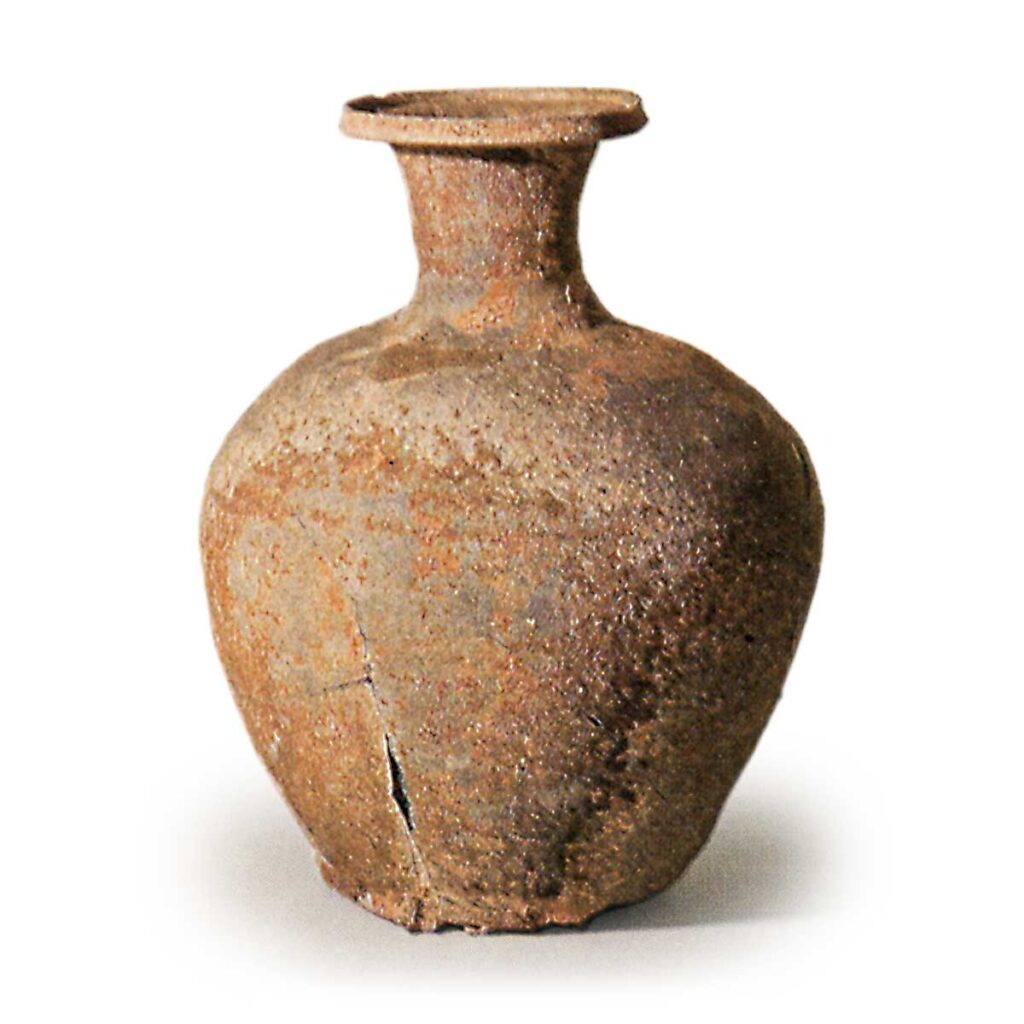

Sue ware can be classified into various types. Sue ware can be broadly classified according to use: for storage, for serving food, for cooking, and for rituals and ceremonies. Sue ware for storage includes various types of jars (bottles).

Sue ware for storage is the most universal of all, and was produced consistently from the time of the first appearance of Sue ware until its end. The shape of the vessels, however, is less varied than that of other types, and they have a rounded base with a mouth and neck that are mostly against the outer surface. Without exception, the body of the vessel was formed by pressing, leaving traces of pressure on the interior and exterior surfaces. The jars are not very well decorated, and the neck of the jar is decorated with only a few comb-shaped patterns. They come in various sizes, but some of the larger jars are much taller than one meter. They may have been used as water jars or for brewing. Next, jars vary widely in shape and can be classified into several types. These include wide-mouthed jars with large, outward-curving neckpieces, straight-mouthed jars with the neck upright, short-necked jars with short neckpieces, and long-necked jars with long neckpieces.

There are also jars with small holes drilled into the body, but these were developed not as utilitarian objects but as offering vessels. Other variants include cho-bi, yoko-bi, and hira-bi. A choibin is a round, flat vessel with ring, hooked projection, or granular ears on both shoulders. The mouth and neck of the bottle may be open or closed. The ears on the shoulders were originally used for tying a cord, and the vessel was hung like a canteen by tying a cord to the ears. However, these ears gradually degenerated and eventually disappeared. A horizontal bottle has a long, round body with a small mouth and neck at the top.

Some flat vases from the Nara period (710-794) onward had handles on the top of the body, while others had a stand. Other special types of Sue vessels include annular jar-shaped jars, rectangular cups, and bird-shaped jars, all of which were decorated in the shape of vessels or animals. Among the various types of jars, those with lids and those with pedestals, handles, ears, etc. are also classified according to the presence or absence of these items. The vessel bases on which round-bottomed jars were placed were also produced from the time of the first appearance of Sue ware and continued to be produced until approximately the latter half of the 6th century. There are two types of vessel bases: cylindrical and bowl-shaped. The most common type of Sue ware for serving food is the lid cup. Cups from the early 7th century and earlier have a rounded base with a lid-receiving return at the mouth rim, and are paired with a lid with a rounded ceiling. Cups made after the beginning of the 7th century are flat-bottomed and have a raised base. The lids are almost always fitted with a bead-shaped knob. Bowls existed consistently from the time of the first appearance of Sue ware to the Nara and Heian periods, but their shapes, like the lids, changed drastically around the beginning of the 7th century.

While some bowls of the first half of the period were decorated with graspers and decorative designs, those of the second half of the period were deep cups or a type of bowl. Related to the bowls of the late period, bowls and other receptacles were also made. Vessels used for serving meals flourished after the beginning of the 7th century, and included plates and dishes of various sizes. They are available in various sizes, and some are equipped with a stand. In addition, there are various types of bowls, although they are not necessarily used for food offerings. One of the most unusual pots is the iron bowl-shaped Sue ware used as tableware for Buddhist monks. There are two types of Sueki pots for cooking: suribachi and suribachi. The steamer has a shell- or deep-bowl-shaped body with a pair of square handles on the body side. The bottom is perforated with several holes. The steamer is a kind of seiro (a cooking stove), in which rice and other ingredients are placed on a jar of boiling water, and the rice and other ingredients inside are steamed by letting the steam pass through the jar. For the pots and jars used for cooking, earthenware with high resistance to secondary heating was used exclusively, and Sue ware was rarely used.

Suribachi is a type of vessel that has existed since the first appearance of Sue ware.

It is a deep bowl-shaped vessel with thick walls and a thick base. Some have small holes drilled into the bottom. The inner surfaces of the vessels excavated from living sites are without exception polished, proving that they were used as suribachi (sliding bowls). In addition to vessels, Sue ware includes a variety of fishing tools such as small octopus pots and pottery weights, as well as pottery inkstones, pottery towers, horses, pottery seals, and pottery coffins. Local Sueki kilns belonging to the Kofun period often fired ceramic haniwa (clay figurines) along with Sueki vessels, which may also be broadly treated as Sueki vessels.

It is estimated that the first Sue ware was produced in Japan in the mid to late 5th century when the technique of ceramic earthenware was introduced from the Korean Peninsula. The first production of Sue ware in Japan took place in the southern hills of Osaka. Soon after, the Hannan hill area rapidly developed as a production area for Sue ware: and the Touyugama kiln was established. The Toei Kiln was the only Sue ware production site for the first few decades after Sue ware production began in Japan. Sue ware from the stage when the Doo-eup kiln dominated Sue ware production is specifically referred to as Early Sue ware. Early Sue ware is generally closely related to ceramic earthenware from the Korean peninsula. Sue ware from this period can be divided into a variety of jars, pots, lidded cups, tall cups, bowls with handles, bowl stands, and other types of vessels, including barrels for long-term storage of liquids and ear cups that were carefully carved and molded on the entire surface. Barrels and ear cups were introduced directly from the Korean peninsula, but they failed to take root in Japan and soon disappeared. The decorative patterns on early Sue ware include straight and wavy designs drawn with a comb, as well as serrated and oblique latticework designs. This extremely Korean pottery-like pattern is limited to this period and does not continue into later phases. The most abundant types of early Sue ware in terms of quantity are jars and pots, while the production of vessels for offering and food offerings is still low. Sue ware from this period is generally carefully finished; for example, concentric circles on the inner surface of a jar have been neatly stroked out. For example, the concentric circles on the inner surface of the jar have been neatly stroked out. The bottom of the cup and the ceiling of the lid have also been carefully scraped without exception. The shapes of vessels generally tend to change from simple to more complex forms. Eventually, Sue ware underwent changes in response to the social and cultural stages and standards of daily life in Japan, and by the end of the 5th century, its Japanization was almost complete.

From the end of the 5th century to the beginning of the 6th century, Sue ware production reached its first major turning point. Sue ware production, which until then had been monopolized by the Tōeugama kilns in Osaka, spread to the provinces for the first time, giving birth to new Sue ware production sites, albeit small in scale, in the Kinki, Hokuriku, Tokai, and San’in regions. In addition, within the Tōeugama kilns, remarkable changes occurred in their products in response to the establishment of local kilns. Sue ware produced at the Tōeugama kilns generally began to boldly omit finishing processes (adjustment techniques) after this first period. For example, the process of erasing the concentric circles on the inner surface of the jar was completely omitted, and the spatula sharpening on the cups and lids was roughened up as a whole. The edges were also treated with less care, and the vessels in general lost their sharpness. The shapes of vessels once again became simpler and more uniform. This trend, which began in the 6th century, was probably part of a mass production system to meet the demand for large quantities. In addition to various types of jars, Sue ware of the 6th century was mainly composed of vessels inherited from the previous period, such as lid cups and high cups, and newly added to these were choke vases and short-necked jars. Later, the production of side vases was also added. On the other hand, certain types of jars disappeared one after another. In this period, the legs of high cups and the mouths and necks of hearses gradually became longer and longer, and eventually lost their original function as vessels and developed only decorative elements. From the end of the 6th century to the beginning of the 7th century, Sue ware production entered a second phase. At the Tōei kilns in Osaka, the kiln structure and kiln construction methods changed at this point, and the types of products and production methods also changed significantly. The number of high cups and vessels, which had been becoming more and more decorated, suddenly decreased, and instead, new types of vessels, such as vessels, plates, long-necked jars, and flat bottles, appeared all at once, mainly at the Tōei kilns. This trend had already been gradually progressing since the latter half of the 6th century, but it exploded at once at the beginning of the 7th century. At this point, the use of choke vases, side vases, and other vessels almost completely disappeared. One of the reasons for this rapid change in Sue ware can be attributed to the changes in daily life that accompanied the active introduction of foreign culture. In response to these changes at the Tōyū kilns in Osaka, this period also marked a second period of proliferation in Sue ware production. In the early 7th century, Sue ware production spread from the Kanto and Hokuriku regions to various parts of Kyushu, and the number of Sue ware produced increased dramatically. The Tōyū kilns, which until then had flourished as the center of Sue ware production in terms of both quantity and quality, were finally losing their leading position, although they still maintained one of the largest production volumes after the second painting period. Later, in the 8th century, national offices and temples were actively built in various regions, and with them, Sue ware production entered a third period of diffusion to all regions of the country. From the end of the Nara Period to the beginning of the Heian Period, the production of ash-glazed ceramics began in the Owari (Aichi Prefecture) region, and the center of the Japanese ceramic industry gradually shifted to this region. It was around this time that it finally became possible to produce small items such as long-necked jars by water-milling. In the early stages of Sue ware of the Heian period, the combination of types and shapes of vessels were almost the same as those of the previous period, but as the period progressed, the types of vessels gradually became more limited and the production methods collapsed. After the 10th century, among the types of vessels produced until then, Sue ware for use in food offerings declined significantly in both type and quantity, and only a few miscellaneous daily vessels such as jars and bowls remained. Although the production of ash-glazed ceramics in Owari also reached a peak for a time, the process of mass production led to a decline in technique and a deterioration in the quality of products, and in the 12th century, kilns that fired ash-glazed ceramics were converted one after another into mountain tea bowl kilns. Sue ware production came to an end, and eventually new kiln production sites emerged in various regions, including the Rokko Kilns. However, the products of the Rokko Kilns and other local kilns beginning in the Middle Ages all followed the traditional techniques of Sue ware production.

The molding process of Sue ware can be broken down into two stages: molding and adjustment. The molding stage can be further divided into two stages: the first and second stages of molding. The first stage of molding is, as a rule, the process of piling up clay strings to create an approximate shape, regardless of the size of the vessel. In the second stage of molding, the molding technique differs depending on the size of the vessel. For large vessels, such as jars, the pressing method is used with a beating board, while for smaller vessels, such as cups, the wheel is used to form the shape. For large vessels, clay cords are piled up to form an approximate shape, and then a wooden tool with a concentric circle engraved on the inner surface is applied to the vessel.

By repeating this process over and over again, any air remaining in the vessel walls is completely expelled to prevent explosions during firing, and on the other hand, the vessel walls can be finished to a uniform thickness. When making a particularly large jar, the clay strings are piled up and the walls are pressed repeatedly, alternately, from the bottom to the top in several layers. Even when using the pressing method, only the mouth neck is adjusted by using the final rotation of the potter’s wheel, but other parts are not adjusted in particular. Early Sue ware jars, however, have the concentric circles tapped on the inner surface stroked off.

Next, in the molding of small vessels, the potter’s wheel is used in the second stage of molding, after first building up the clay strings to create the elementary shape. For example, in the case of a cup body, the elementary form is first fixed on the potter’s wheel to prepare the vessel, and then details are drawn out or shaved off at unnecessary parts to form the vessel. Although shaving is the second stage of shaping, it can also be considered a type of preparation technique. In addition to spatula shaving, there are other adjustment techniques such as horizontal stroking and kakime. When the molding adjustment is almost complete, additional items such as handles and ears are glued on, and patterns are drawn using a comb or spatula. Most of the patterns drawn with a comb are parallel linear or wavy patterns using the rotation of the potter’s wheel, and only early Sue ware has drawn patterns. Earlier, I mentioned that, in principle, the molding of Sue ware is based on the piling up of clay strings regardless of the type of vessel, but from the early ninth century, the method of molding on the potter’s wheel began from the first stage of molding. In other words, this method involved placing a lump of clay on the potter’s wheel and molding it all at once while rotating the wheel. Long-necked vases and small vases of the Heian period were formed by Minato’s water wheel. In addition to this method, molds were also used in rare cases.

The kiln in which Sue ware was fired had a single-chamber structure with a tunnel-like structure from the fire mouth to the smoke outlet. The kiln has a single-chamber structure in the form of a tunnel from the fire mouth to the vent. The firing chamber, firing chamber, and vent are located in order from the fire mouth to the back. There are two types of kiln bodies: tunnel type (underground type), which is completely hollowed out of the ground, and semi-underground type. To construct a semi-underground kiln, a long trench-like pit is first excavated into the hillside, and a ceiling is erected above the pit. For the ceiling structure, a dome-shaped framework is built in advance using logs and thin tree branches, and then clay with tin is pasted on top of it. At the same time as the ceiling structure, the inner walls of the kiln body are coated with a layer of clay containing tin and adjusted to the unevenness of the walls, taking the condition of the sagging into consideration. Sue ware kilns vary in size, but the average size of a Kofun period Sue ware kiln is about 10 meters long, the maximum width of the firing area is about 2 meters, and the vertical height from the floor to the ceiling is about 1.5 meters, while kiln bodies of the Nara and Heian periods are generally slightly smaller in scale than this. The floor of a Sue ware kiln is usually sloped, but some are almost horizontal. When the floor slopes gently, the chimney is lengthened to strengthen the fire. In the case of Sue ware kilns with a staircase-shaped floor, roof tiles are fired at the same time in all cases. Kilns of such a form were sometimes constructed after the early seventh century. The floor is generally covered with finely crushed gravel or kiln wall lumps that are difficult to melt, making it easier to hold the products in place when the kiln is filled and preventing them from fusing together. Each time the kiln is fired, the damaged parts of the kiln walls are repaired and a new coat of clay is applied. The walls of kilns used for long periods of time are thus covered with multiple layers of clay, but most kilns in such a state belonged to the early 7th century or earlier, and after that, new kilns were built one after another instead of being repaired. Generally, Sue ware is said to have been fired by reduction firing, but in reality, it was not consistently fired by reduction firing. At first, the kiln mouth is opened to allow air to flow into the kiln for oxidizing firing. When the temperature inside the kiln rises and the products are almost ready to be fired, the air is extremely limited and a large amount of fuel is injected to create a reduction state. The blue-gray color of the Sue ware is due to the temporary reduction firing in the final stage of the firing process. Sue ware fragments often have a blue-gray front and back with a brownish-brown core, which is proof of the existence of the firing method described above. Sue ware is usually fired at high temperatures of around 110 to 120 degrees Celsius, and the clay used to make it must naturally be able to withstand such temperatures. There are two types of clay, marine clay and freshwater clay, and marine clay has a refractoriness of less than 1150 degrees Celsius and is not suitable as a raw clay for Sue ware. The potters who made Sue ware knew this empirically and used only freshwater clay for the production of Sue ware.