A lathe for forming ceramics. The wheel is used to form ceramics by placing clay on a board and turning it, and then pulling up the clay using the turning motion.

In Japan, the potter’s wheel is not only used for forming ceramics, but is also used for the wheel on the top of a tsuribin well, a wheel plane for woodworking, a wheel base (vise), and an umbrella tool (kasatsubaki). In China, only the wheel of a pumping vessel (the wheel of a tsuribin well) and a squeegee (wheel base) are called a potter’s wheel, while a potter’s wheel for forming ceramics is called a wheel of equal weight, a wheel of weight, a potter’s wheel, a wheel wheel wheel, etc., with the characters of mud wheel, wheel of discipline, weight of luck, lathe, and potter’s wheel being used for them. In Korean, the potter’s wheel is called “murni,” and the Chinese character “ryuntae” is used. English potter’s wheel, German Drehscheibe, French Tour [Structure and Types] A potter’s wheel consists of a molding disk and a supporting axle, the lower end of which is buried in the ground and fixed. The disk, which is stabilized horizontally at the top of the axle, is turned by hand, foot, or power. A ceramic or steel top is fitted at the point of contact between the shaft and the disk to prevent wear and tear, and the surface of the disk is generally at the same level as the floor on which the potter sits and works. The surface of the disk is generally the same height as the floor on which the potter sits and works. Wooden ones are most commonly used, and zelkova wood is often used in both Japan and Korea. The earthenware made at the Dehua kiln in China is considered to be one of these types, while the clay disks obtained by Laufer at a kiln in the suburbs of Beijing in 1903 have a hat-like shape and are made by mixing clay with pig hair and medicine and then drying and hardening them. The stone ones are found in China and India, and the one Laufer obtained in Shanxi Province, China, was a heavy stone disk with a disc on top. Examples of ceramic wheels can be found in the small potter’s wheels used to draw painted circle lines. The potter’s wheel is divided into three types according to the type of operation. The manual hand wheel, the foot-operated kick wheel, and the power-operated mechanical wheel. The hand wheel has several holes drilled around the forming disk, into which a turning rod is inserted to turn the wheel. Unlike the single-disc type of the hand wheel, the kick wheel is a double-disc type, in which the lower disk is kicked to form the upper disk (some single-disc types are kicked with the foot). The mechanical wheel is turned by power and has a moldboard (trowel) for molding.

The origin and spread of the wheel: A brief translation of Laufer’s “The Origin of the Wheel” is as follows. Some people believe that the first turning device in primitive pottery production was a shallow basket, a piece of gourd, or a round stone, and that this device was the first step toward the invention of the potter’s wheel, but this is not true.

The two methods of pottery-making, primitive handmade and later wheel-thrown, are fundamentally different expressions of two different human activities. The potter’s wheel was a new phenomenon that emerged from outside the potter’s wheel when the pottery industry, which had previously been in the hands of women, was later managed by men, and indeed, the wheel is the origin of the wheel’s ingenuity. The wheel, which is still used by the Tamil people today, is a primitive wheel, made of a bundle of long, thin, flexible wood strips or bamboo, with a diameter of about one meter, and a thick coating of goat’s hair or similar material mixed with clay. The four wheels and the place where the centerpiece is placed are made of wood. The central rod is made of hard wood or stone. The wheels have one or two slightly concave sections, into which the handles are placed so that the wheel can be turned.

The turning is first done by hand, and then a long piece of bamboo is inserted into the concave part of the wheel to make a quick turning motion. The Assamese potter’s kilns are almost the same as this one. The fact that the potter’s wheel was probably not developed from handmade tools, but was inspired by the wheel, can be seen in the fact that in China and India, even after the development of the wheel, handmade craftsmen and wheelwrights are still considered to be completely separate and distinct from each other. The same can be seen in Hindu scriptures and in Chinese characters for wheelwheel. The origin of the potter’s wheel in the world seems to have gradually spread from two centers. The first appeared in Egypt (in the second millennium B.C. or earlier) and gradually spread to southern Europe, and then to central and northern Europe. The other originated in China, reached Korea and Japan, and then reached Annam and Burma. India can be seen as the other focal point, and it seems to have spread from there to Sumatra and Hawaii. However, it is difficult to conclude that the lineage of the transmission of the potter’s wheel is completely unrelated to each other and multifaceted.

In China, pottery wheels used for forming ceramics are called “chun,” “wheel wheel,” and “potter’s wheel,” as already mentioned above.

In addition, in the Koukouki, it is written that the potters of that time were divided into two groups: potters (who used the potter’s wheel to make daily utensils) and turners (who used the wheel to make ritual vessels).

The “Koukouki” also describes that the potters of that time were divided into two groups: potters (who used the potter’s wheel to make daily necessities and potters who used the wheel to make ritual vessels). The potter’s manual “Tosaeshiki” also describes in the article of “Tosaeshiki” that the potter was divided into two groups: the potter (who made daily necessities on the potter’s wheel) and the potter (who made ritual vessels by using the potter’s wheel). The form of the round vessel is determined according to the following methods: “The person holding the bowl sits on a frame and uses a bamboo stick to hit the wheel and drive it on a wheel. According to the “Inspection Report on the Ceramic Industry in the Qing Dynasty,” the Jingdezhen potter’s wheel is manual and generally similar to the hand wheel in Japan, with disks usually ranging from 96 cm to 1.3 m in diameter and around 6 cm thick. There is a ceramic bearing at the point of contact between the disk and the axle. There are four wooden rods surrounding the shaft and a ceramic ring attached to the lower end of the wooden rods. The tops of the shafts are made of hardwood and replaced when impaired. The potter sits on the waistboard with his legs spread out in front of him, holds a rod with both hands, and inserts it into a hole drilled in the disk to rotate the disk. The turning rod can be made of bamboo or wood and should be one meter or less in length. When making large vessels, however, an assistant worker is required to turn the disk, and some vessels may require three assistants. Pottery wheels made at the Dehua kiln in Fujian Province are on legs, which differs from those made at the Jingdezhen and Shihwan kilns, as well as from those made in Japan. In other words, it has a wooden cylindrical foot on a wooden shaft. Nine stakes are driven at right angles into the upper plane of the cylindrical leg, and bamboo pieces are attached to the stakes to form the seat. The diameter of the disk is usually between 54 and 60 centimeters. To turn the disk, the potter sits in front of the wheel, lifts his right foot, and kicks the edge of the disk. When slow rotation is required, this may be done by hand, and a small cup is embedded in the edge of the disk to serve as a handhold. The diameter of the potter’s wheel of the Shiwan kiln in Guangdong Province is about 75 cm, and the height of the wheel is about 15 cm above the ground on a wooden shaft placed in a hole in the ground. The potter and the assistant always use the potter’s wheel. The assistant stands by the potter’s wheel and holds a suspension rope hanging from the back of the house to hold his body in place, while the potter lifts his legs and kicks the top of the wheel. The wheel is similar in structure to the hand wheel in Japan, but the operation is similar to that of the kick wheel.

The wheel is made of zelkova wood, and only the shaft is made of ebony wood. The double-disc type is very similar to the kick potter’s wheel used in the Kyushu region of Japan. The upper board is about 48 cm in diameter and 9 cm thick. The lower board has a hole in the center through which wood is threaded. The upper and lower boards are connected by four wooden rods, and the shaft wood receives the upper board, passes through the hole in the lower board, and is fixed to the ground at the lower end. The entire potter’s wheel is installed in a hole dug in the ground with a diameter of 90 cm or less, and the upper board is placed as if it were on a level with the ground plane. The potter sits on a wooden board placed in a hole dug at his side, and molds the vessel while kicking the lower board.

Japan: The origin of the potter’s wheel in Japan is also unclear. The Shosoin document “Zobutsu-sho Sakubutsu-cho” mentions “potters in Omi” and it is clear that the potter’s wheel was used in the Tempyo period (729-49).

In Japan, the single-disc hand wheel and the double-disc kick wheel are used side by side, with the two showing opposing forces in accordance with the traditions of each pottery region. The hand wheel is mainly used in Owari (Aichi Prefecture), Mino (Gifu Prefecture), Banjo (Fukushima Prefecture), and Kyoto, and is also called the Seto wheel.

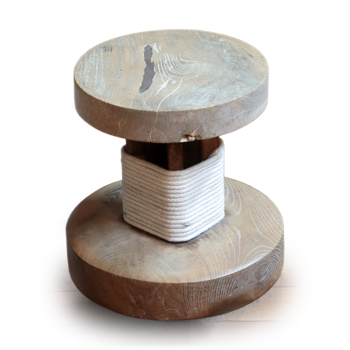

The structure generally consists of a molding disk and a hollow cylinder attached to the center of the back side of the disk, with a spindle inserted inside to support the disk. The lower end of the shaft wood should be fixed in the ground. A small hole is drilled in the disk for inserting a turning rod. The dimensions vary slightly from region to region, but generally the diameter of the disk is between 54 cm and 66 cm, the thickness is between 75 cm and 90 cm, the outer diameter of the cylinder is 14.5 cm, and the length of the cylinder is about 42 cm. The wheel is mainly used in Kyushu, Tajima (Hyogo Prefecture), Izumo (Shimane Prefecture), Nagato (Yamaguchi Prefecture), Iyo (Ehime Prefecture), and Kaga (Ishikawa Prefecture). It consists of an upper and lower board, both of which are usually connected by four wooden mallets. The shaft of the upper board is held by the lower board through a hole in the center of the lower board, and the lower end of the shaft is fixed in the ground. The lower board is kicked around with the foot and formed with the upper board, which is the same as the Korean style. The dimensions vary slightly from region to region, but usually the upper board is 30 cm in diameter, the lower board is between 4 cm and 54 cm in diameter, and the length of the wood connecting the two boards is about 30 cm. However, the upper plate of a Satsuma daisya (large wheel) has a diameter of 93 cm and a total height of 63 cm. In the “Pottery Instruction Manual,” a diagram of a stone potter’s wheel is shown, with the following explanation: “Also called a keri rocuro, the wheel is 8″ across the mirror and 1.8” high, and the middle is wound with a rope as shown in the diagram. In Kaga, there is an ancient hand-painted potter’s wheel. In Kaga, the hand-pulled wheel was called the “earthen wheel,” and the kicked wheel was called the “stone wheel. The potter’s wheel in Japan was originally a Chinese-style hand-propelled wheel, but later, when the Korean porcelain method spread to the Kyushu region, the wheel-kicking method was also introduced, and it seems likely that this method was also introduced into Japan together with the Kyushu porcelain method. In Seto, however, the method of using the kick potter’s wheel was introduced along with the Kyushu method during the Bunka era (1804-18), but the tradition of using the wheel by hand was so strong that the kick potter’s wheel did not become widespread. The same is true of Kyoto and Aizu. In the Kyushu region, the kick potter’s wheel is called “Kuruma (wheel)” without using the term “potter’s wheel,” and the hand potter’s wheel is used only for the attachment of painted circle lines, which is also called “Suji Kuruma (wheel). In Hizen, the wheel is called “Kuruma-goinjo,” “Kuruma-zaiku-jin,” “Kuruma-tsubo,” “Kuruma-opening,” and so on. The term “potter’s wheel” is generally used east of Kyoto, but there are some places, such as Shigaraki, where the term “wheel” is also used. Most of them are made of wood, mostly zelkova, but some of them are made of Japanese pagoda tree (koujou). The wood used for the shafts is often zelkova, and for the rods, oak is often used. Recently, however, steel is often used for the wood for the shaft. The small potter’s wheel for painting is usually made of metal, but in the Seto area, a ceramic wheel is also used. Under the modern factory system of production, the use of the hand wheel and kick wheel has gradually declined, and the use of the machine wheel and other methods of molding have become the norm. There is a remarkable feature of wheel-thrown tea containers called “itokiri. Itokiri is a mark that is produced on the bottom surface when the potter separates the tea caddy from the rest of the potter’s wheel using the momentum of the wheel after molding. However, this distinction is not essential (see the section on “Ito-kiri”). The striations that appear around the vessel during the molding process are called “wheel marks,” and are also sometimes a point of interest. Wheel-thrown molding is called nuta-biki in Seto and mizu-biki in Kyoto.