Tenmoku, Setoguro, Kizeto, Shino, Oribe, Hakuan

Although Shino tea bowls are so highly valued today, they were never made in the old tradition. When “Taisho Meikikan” was compiled more than 40 years ago by Yoshio Takahashi, a versatile tea master, there were only nine Shino, Oribe, and Kizeto tea bowls in the book, and only six of them were Shino. The tea master from Nagoya, Mr. OBIAN, did his best to compile the book, and his efforts in searching for the best bowls were beyond our ability, yet only six Shino bowls were included in the book. Of course, it is not that Archenan did not know where to find Shino tea bowls, but it clearly reflects the fact that the general public at that time did not have a deepened awareness of Shino.

The increased interest in Shino tea bowls was probably due in large part to the book “Shino, Kizeto, Oribe” edited by O. Morikawa Kanichiro Jyojunan, published in 1936. The book contains 18 Shino bowls from the past, all in their original colors, and it can be said that the current appreciation of Japanese Shino ceramics was enlightened by this work. Gradually, Shino was reevaluated by scholars and potters, and appreciation of Shino among the tea masters naturally grew, and has continued to this day.

Incidentally, looking back at the history of prizes for Shino tea bowls, it is obvious that Shino tea bowls were popular at that time because they were Momoyama tea bowls, but after the early Edo period, especially after the Enshu period, prizes for Shino tea bowls clearly focused on Korai tea bowls, followed by Raku tea bowls since Rikyu, and then Karatsu and Hagi, and there was not much interest in Shino and Oribe tea bowls. and Oribe, and there seems to have been little interest in Shino and Oribe. Therefore, they were not included in the “Meimono” or “Chuko Meimono,” and not a single bowl was included in the representative Meimono of the Edo period, such as “Enshu Kurachou,” “Ganko Meimono Ki,” and “Chuko Meimono Ki. It is assumed that Shino’s position in the tea ceremony, especially among the feudal lords, declined dramatically because of this lack of attention.

Although this was the general trend during the Edo period, some tea ceremony sakyos, especially among the townspeople, were more fond of it than one might think. As an example, it is known that “Uka-pai” was handed down to the Fuyuki family, a wealthy merchant in Edo who prospered during the Genroku and Genbun periods, and several bowls were also handed down to the Konoike family in Osaka. It is also known that several bowls were handed down to the Konoike family in Osaka, and it can even be said that they were people’s tea bowls. However, they were very small compared to Korai tea bowls and Raku tea bowls.

It is also noteworthy that three Shino tea bowls are included in the collection of Matsudaira Fumai, a feudal lord tea master at the end of the Edo period. Unshu Meibutsu-ki” is different from the previous “Meibutsu-ki” in that it was collected based on Fumai’s own knowledge, and Shino teabowls were at least more recognized here than in the “Gan-kan Meibutsu-ki” period. This may reflect the fact that the lord’s collection was mediated by a tool dealer.

It was not until the modern age that the existence of Shino tea bowls was further enhanced and their beauty came to be recognized both in name and reality, when they came to be prized by sukiya (tea masters) such as Mitsui Takayasu and Masuda Nunoo. The tea ceremony utensils included in this volume have been preserved in the museum since the 1960s.

The tea bowls included in this volume are not only Shino, but also Seto Tenmoku, Seto Shiro Tenmoku, Setoguro, Kizeto, Kuro Oribe, Aka Oribe, Hakuan, etc., but it can be seen that Shino is the main type.

Tenmoku of the Muromachi Period

The appreciation of karamono tenmoku tea bowls, represented by yohhen tenmoku and aburitake, reached its peak in the Kitayama and Higashiyama periods, with yohhen and aburitake being prized to the extent that they were called “ten thousand pieces” and “five thousand pieces,” respectively.

The taste of the time naturally prompted the appearance of imitations in our own pottery kilns, as if water were running low, and pottery production began in the ceramic kilns of Owari and Mino. However, it is not clear when the manufacture of Tenmoku tea bowls in Seto began. According to excavations of old kiln sites, it is said to date back to the early Muromachi period, but it was not until the Tenmon period (1336-1573) that they first appear in major records of the Muromachi period, and it is therefore assumed that the general demand for Tenmoku tea bowls also increased at that time.

The most representative types of wamono tenmoku from the Muromachi period that have been recorded are Ise-tenmoku, Seto-tenmoku, and Shiro-tenmoku, of which Seto-tenmoku has a relatively clear provenance, and it is likely that this type was fired in Seto, Owari. Various guesses have been made about Ise-temmoku and Shiro-temmoku, but their provenance has yet to be determined. As mentioned above, Seto Tenmoku and Ise Tenmoku came into general use in the late Muromachi period (1532-1555), but there is a record that Murata Shuko, the founder of Wabicha, who died about 30 or 40 years earlier, in 1502, is thought to have used Ise Tenmoku during his lifetime. There is a record of it. It is in the words of Shukoh in “Zenpō shinraku dangi” by Kinshun Zenpō, in which he describes his own tea sukiyō.

The following is a quote from a Zenpō Zenpō’s “Zenpō Shinraku Dangi” in which Shūkō describes his own tea ceremony techniques: “Even though I try to use a …… gold wind furnace, a yōko, a mizusashi, and a mizukoposhi, they should not stain, and even if it is an Ise or a Bizen, it should look interesting and beautiful.

It is assumed that the “Ise-mono” mentioned in the article may have been Ise-tenmoku.

Leaving the Shuko period aside for the moment, by the time of the Tenmon period, which can be said to be the Shaowo period, Seto tenmoku and Ise tenmoku, along with Karamono tenmoku, had come to be used as the tea bowls of the day.

In other words, “Ise-tenmoku” was mentioned in the “Reiunzenin Jouju Kouwari” of 1548, and “Seto-tenmoku” and “Hakutenmoku” were mentioned six years later in the “Chagu-biyoju” compiled by Ippuken Sokin in the 23rd year of Tenbun.

The Seto tenmoku is described as follows

Seto tenmoku is a type of stone or tin or lead covered with a ring.

Compared to karamono, which were mainly covered with gold or soft wrought rings, Seto tenmoku seems to have been of a much lower grade.

Furthermore, in “Nihon Ichikan” written by Zheng Shungong in China around the Eiroku period, it is written that

In “Nihon Ichikan” written by Zheng Shun-kong in China around Eiroku period (1588-1591), there is a description “Tea bowls from Owari are very colorful and black, and his dance is the most beautiful pottery, hence the high price. However, the fact that a Chinese person wrote this down tells us that Owari ceramics, including Seto Tenmoku, were quite prosperous at that time.

After Seto tenmoku, Ise tenmoku often appears in tea ceremony records, and is described in the above-mentioned “Reiunzenin Jouzumi Giwari,” a catalog of fixtures from Reiunin, the pagoda of Myoshinji Temple in Kyoto.

Ise-tenmoku with silver cover

The first example of the Ise Tenmoku is described in “Tsuda Souryou Chayu Nikki” (Diary of Souryou Chayu, Tsuda Souryou, Kyoto) as

Ise Tea Bowl, Morning of December 12, Eiroku 4, Kanataya Sobeiwatsukai

Ise Tenmoku Shiroi, New Year’s Day 11th morning, 9th year of Eiroku, Michibetsu-kai

In the “Imai Munehisa Chayu Shokubetsu” (Imai Munehisa Chayu Shokubetsu), there is also an inscription that reads

Ise-tenmoku, February 20, Eiroku 10, morning, Ryusenkai.

Furthermore, in the “Kamiya Sotan Diary,” from the 18th day of the 15th month of Tensho to the 25th day of June of the same year, there are five references to “Shiroi isetenmoku,” “isetenmoku,” “tenmoku haise shinya,” and “isetenmoku shin,” among others. In particular, the tea ceremony on the morning of June 25,

Ise-tenmoku-shin, June 25, Tensho 15, morning, Hakozaki Kanpaku-kai

This indicates that the Shin-yaki Ise-temmoku was used for Hideyoshi Sekihaku’s tea ceremony.

According to the above, it is clear that the Ise-temmoku was used as the first-class tea bowl for about 40 years from Tenmon to Tensho, and that there were both black and white tea bowls. However, there is no known “Ise-temmoku” tea bowls in the history of Japan, and it is not known what kind of tea bowls they were. However, as for its place of origin, it is mentioned as a famous product of Mino Province in “Kebukisou” edited by Shigeyori Matsue, who was a genius in the haiku world at that time, in Kan’ei 15, as follows

Seto ware is said to be produced in this country, and is called “Fujishiro-tofujirou” and “Ise-temmoku”.

Ise-temmoku” is listed as a specialty of the Mino Province, and the answer is noteworthy in guessing the place of origin of Ise-temmoku.

The reason why tenmoku fired in Mino was called Ise-tenmoku is that Ise Goshi had a close relationship with the Mino region at that time, and it is considered that he ordered tenmoku from Mino to be served to his guests from various countries, and these were called Ise-tenmoku (see Tadanari Mitsuoka, “Japanese and Ceramic Ware”).

Furthermore, since tenmoku from the Muromachi period has been excavated from kiln sites in Mino such as Kugiri, Gotomaki, Jorinji, and Akasaba, and white glazed tenmoku from Tensho, Keicho, and later from kiln sites in Oyaya, Ohira, and Motoyashiki (see Toyozo Arakawa, “Shino”), it is likely that one of these kilns produced the “Ise Tenmoku White” used in Eiroku 9. It is probably safe to assume that one of these kilns fired “Ise-tenmoku white” used in Eiroku 9 and “Shiroi-ise-tenmoku” used by Ikeda Iyo on the evening of the 18th day of the 18th month in Tensho 15 (Sotan Diary).

Therefore, it is likely that “Seto Tenmoku” and “Ise Tenmoku” used in the Muromachi period were made in Seto and Akazu, as described in “Chagu Biyou Shu”, and Ise Tenmoku was the common name for Mino Tenmoku, but further research is needed to determine the details.

Another item that must be considered in connection with the “Ise Hakutenmoku” is the “Hakutenmoku” that is said to have once belonged to Takeno Shao’o. It is currently in the possession of two bowls. One is a tea bowl that came from the Tokugawa family in Bishu, and the other is a tea bowl that came from the Maeda family in Kaga. The Maeda family’s tea bowl is inscribed with “Shaooseto Hakutenmoku” by Sen no Rikyu, and is accompanied by a letter from Rikyu to Yakushiin in Sakai, which reads,

The letter also includes a letter from Rikyu to Yakushiin in Sakai, which reads, “The Shaooseto Hakutenmoku, now in the possession of the Lord Kanpaku (Hideji), is requested by Chotoko-bo to be kept in the possession of the people of Sakai.

It is clear that Shaowu owned this bowl, and it is also certain that it was fired before the first year of Koji (1555), the year of his death.

Both bowls are of similar workmanship, and it is assumed that they were fired in the same kiln at almost the same time, but it is not known where they were fired, and this work is attracting attention among researchers today.

According to “Shino” by Toyozo Arakawa, “Unfortunately, the kiln that fired the white tenmoku of Shao’o has not yet been discovered, but it is almost certain that it is an early Shino (……),” and the reason for the original Shino style is that “these two tea bowls were either burned in Seto or Mino. It is difficult to say at this point whether these two tea bowls were burned in Seto or Mino, but from the point of view of the glaze, they are by no means Ki-Seto. It is a feldspar glaze. It may be mixed with some ash, but especially the Tokugawa family’s ware must have been fired naked without being put in a pod (……). However, the kiln in which they were fired is not clear, and the kiln site of Jorinji, which fired tenmoku in the Muromachi period, “In addition to Kizeto and tenmoku, a very small amount of Shino was found, so I would like to examine the kilns around Jorinji and Gotomaki more carefully.

By the way, according to my theory that “Ise Tenmoku” and “Ise Tenmoku Shiroi” were made in Mino as mentioned above, if these two white tenmoku bowls were made in Mino, they are older than the “Ise Tenmoku Shiroi” from Eiroku 9, and if “white tenmoku” is an early Shino ware, then Ise Shiro Tenmoku was also an early Shino ware. If “Hakutenmoku” is an early example of Shino, then Ise Hakutenmoku must also have been an early example of Shino. However, the problem here is that Rikyu refers to Shiro-tenmoku as “Seto,” but in this case, “Seto” was an idiomatic term of the time, rather than “Seto” from Owari, as in “Kebukisou” where Mino ceramics are referred to as “Seto Yakimono” and in the Momoyama Chakai Ki where all Mino ceramics are referred to as “Seto. It is probably safe to say that “Seto” was an idiomatic term at that time rather than “Seto” of Owari. In the case of “Ise-temmoku,” it is thought that the term “Ise-temmoku” was also used to refer to the Mino tenmoku, which was limited to the tenmoku produced in Mino. In other words, it can be understood that some Mino Tenmoku had the character of special demand from Ise.

In any case, there are still many unanswered questions about Tenmoku tea bowls of the Muromachi period, and the review of the existing works remains as a major issue. In “Taisho Meikikan”, in addition to the tea bowls in this volume, “Koseto Tenmoku”, “Kiwa Tenmoku” of the Murayama family, and “Kiwa Tenmoku” of the Maeda family are mentioned as Seto Tenmoku, and as for Kikka Tenmoku, the tea bowl in volume 7 of “Sekai Tokugaku Zenshu” is impressive as an excellent work of art.

Seto Tea Bowls of the Momoyama Period

From the end of the Muromachi period through the Momoyama period, the term “Seto ware” is often used in many tea ceremony books and tea ceremony diaries. In particular, Seto tea bowls, together with Chojiro’s Raku tea bowls, which were generally called “Ima-yaki” at the time, were the flower of Japanese tea bowls at Momoyama tea ceremonies.

The use of Seto tea bowls increased dramatically from around Tensho 14 or 15 and reached its peak. However, most of the “Seto tea bowls” used here were not the so-called Seto ware of Owari, but were made in kilns scattered in Toki and Kani counties in Mino. Therefore, Seto tea bowls in this case should be referred to as Seto ware in Mino, or Mino Seto ware, as noted in “Kebukisou,” but it is assumed that it was used as a general term for both types of pottery at that time, without distinguishing between Mino and Owari.

As mentioned in the previous chapter, Kizeto ware of tenmoku and chrysanthemum-plate handles had been produced in Mino since the late Muromachi period (1336-1573), and the hotbed for the flowery flowering in the Momoyama period had already been established, but what directly influenced this flowering was the migration of workers from Owari Seto under the patronage of Nobunaga Oda after he conquered Noo, which also led to its prosperity. Furthermore, the unification of the country by Hideyoshi stabilized the public sentiment, and the tea ceremony was driven by the tea masters of Sakai and Kyoto, who were playing a leading role in the tea ceremony of the time. The market was thriving as never seen before. In addition, the active efforts of Sen no Rikyu and Furuta Oribe, the two great tea masters of the Momoyama period, who were responsible for the tea ceremony of the early and late Momoyama periods, played a major role in bringing this new form to the limelight of the times.

Setoguro, Shino, Kizeto, and Oribe were born from the environment described above, but as seen in the above tea ceremony notes, they were not classified by type as we do today, but were all treated as “Seto Tea Bowls”. Therefore, it is almost impossible to determine which Seto tea bowls were used for which tea ceremony and when. However, for example, let us take a look at the tea ceremony held by Rikyu at Jurakudai in Kyoto on September 10, noon in the 18th year of Tensho,

Seto Chawan (tea bowl) was brought out and replaced by a black bowl on the dais, and the tea was served in black.

It is possible to speculate that the non-black “seto tea bowl” that Rikyu deliberately replaced because Taikoh Hideyoshi did not like black tea bowls was probably a white- or yellow-glazed one, or that it was the so-called Shino tea bowl.

The “White Tea Bowl” used for the tea ceremony of Mitsunari Ishida in Hakata on November 23, Keicho 3, and the “White Tea Bowl Seto” used by Hisamasa Matsuya in Nara on Ugetsu 18, Keicho 6 in the “Koori Densho” are also thought to have been Shino.

It is also interesting to note that on the morning of February 28, Keicho 4, Furuta Oribe’s tea ceremony in Fushimi is described as follows

The “Sotan Diary” indicates that Furuta Oribe held a tea ceremony using mostly Seto ware utensils, and used a tea bowl with a distorted, frightening appearance, which must have been the Oribe Black Kutsu Tea Bowl, and that this type of distorted Seto tea bowl was used in a tea ceremony held on the morning of February 8, Keicho 9, 1896, in the Kuroda Chikuoka Furthermore, a Seto tea bowl with this kind of distortion was also used at a tea ceremony held by Kuroda Chikushu (Nagamasa) on February 8, Keicho 9, 1896, and “Tea Bowl Seto Yari Hitsumutsukidou” was written by Kamiya Sotan, as well.

From the descriptions in the tea ceremony notes such as these, we can see that Shino-like items were used in Tensho 18, and Oribe-black Kutsu chawan (tea bowl) was used in Keicho 4.

Among Seto tea bowls of Momoyama, Setoguro is said to have been the earliest to be fired, except for Tenmoku. However, since Setoguro, Shino, and Kizeto were all excavated from kiln sites, there does not seem to be much difference in time between them, and it would be more appropriate to consider the date of manufacture based on changes in shape, pattern, and other styles throughout the entire range. Here, however, we only describe the characteristics of each type of ware.

Kiseto

There are very few Kiseto tea bowls. The only one that has survived that was originally made as a tea bowl is said to be the “Asahina” bowl that was handed down in the Mitsui Hachiroemon family and is inscribed directly by Sotan.

Most of the other bowls are thought to have been made for the other side of the bowls and then converted to serve as tea bowls. The low and large base of the bowls are not exactly the same as the base of a tea bowl, and therefore, three bowls such as “Naniwa” in this volume are excellent works, but they were originally made to be mounted on the other side.

There are other tea bowls with transparent yellow glaze similar to that of Kosedo, which are not shown here, but are commonly called Hakuan-te, and some of them are from the Muromachi period, and are considered to be the precursors of the so-called Ayame-te Koseto. Moreover, it is interesting to note that the form of these bowls is apparently similar to Jukko celadon, and they may have been fired together with Tenmoku as a copy of celadon. Therefore, it is conceivable that the “Seto tea bowls” used in the old days may have been of the same type.

By the way, “Asahina” is a unique work for Ki-Seto, as I have already mentioned, but since the form and tone of work using spatula are similar to Shino tea bowls such as “Hatsune,” it can be said that it was fired in Mino in the early Momoyama period. However, since there is no other similar piece, it is thought to have been a work specially ordered by Osoragu.

The cylindrical tea bowls made for muko-tsuke are all Ayame-kiseido, but they are characterized by having a common style, such as having a striped body, engraving a floral arabesque pattern on two sides, and applying a bold glaze.

The best examples are said to be those fired at Oyayaki. The mild and heartwarming coloring of the yellow glaze of fried skin dotted with green bold boldness, along with the white glaze of Shino, gave this pottery a very Japanese sentiment. It can be said to be pottery.

However, the glaze tones varied depending on the firing conditions, and very few of them are as well made as the three bowls shown here.

Shino

Nagalithic white glazed pottery, known today as Shino, is believed to have been produced in the kilns of Mino or Seto since the late Muromachi period (1333-1573). Of course, the Shino tea bowls included in this volume were all fired after the Momoyama period, and the early works were all tenmoku tea bowls. The white-glazed tenmoku is considered to be what was called “Ise white tenmoku” at that time, and there were also other tea bowls called “Seto white tenmoku” such as the one owned by Shao’o. In the Momoyama period (1573-1600), these were developed into the so-called Shino tea bowls, which were painted with iron glaze and covered with white glaze.

By the way, there are various speculations as to when the name “Shino tea bowls” originated.

As far as records show, it was not until the Edo period (1603-1867) that the term “Shino” came to be used for Momoyama Shino, and there is no record of this in Momoyama tea ceremony records. In all cases, it is simply called “Seto Tea Bowl” or “White Tea Bowl,” and there is no such name as “Tea Bowl Seto Shino” that can be found. If this is the case, it is unfortunately not clear at present whether they were not called “Shino” at the time of firing or why they were called “Shino” in later periods.

However, one of the tea bowls frequently used in “Tsuda Muneyoshi Chayu Nikki” and “Imai Munehisa Chayu Shokudan” from the period of 22 Tenbun to 14 Tensho in the Muromachi period is called “Shino Tea Bowl”.

Moreover, this Shino tea bowl was used only by three persons, Shao’o, Munehisa, and Muneyoshi, suggesting that it was the name of a special tea bowl, of which there were only two or three at that time. However, it is not clear what kind of tea bowls they were, and neither are they mentioned in tea books or tea ceremony records. However, there is a “Tea Ceremony Instruction Scroll” in the collection of the Morikawa family in Nagoya, which was addressed to Sotoku by Sen no Rikyu. (It is thought that the “Shino tea bowl” may have been Shino Tenmoku, or that the Shino Tenmoku may have been a white glazed Tenmoku from which the name “Shino” originated.

However, the relationship between this Shino tenmoku and the Seto white tenmoku owned by Shao’o and the Ise white tenmoku is unknown.

There are the following types of Shino tea bowls fired after the Momoyama period, but it is not clear when they were first produced. If the Shino tea bowls that Rikyu replaced with black tea bowls on the pedestal were already being produced in Tensho 18, they probably began in the middle of the Tensho period. The Seto Bowls were probably started in the middle of the Tensho period. And as a general theory today, it is believed that the oldest tea bowls were cylindrical tea bowls similar in shape to Setoguro, and gradually changed to the so-called Oribe taste with a strong artifice.

Plain Shino

These are simple tea bowls with no painted or carved patterns, and the entire surface is covered with a white glaze. Among the plain Shino, a tea bowl owned by Furuta Oribe, which was handed down to the Yabuuchi family in Kyoto, is of an ancient style and looks very similar to the Seto-Black tube. The “U no Hana” tea bowl in this volume is also of excellent workmanship.

Shino

Shino is the most common type of tea bowl, in which the painting is done in iron glaze (oniita) and white glaze is applied over the painting. It is the core of the Shino tea bowls in this volume, including “Uka-pai”. The works of Ohgayan are the best.

Nezumi-Shino

The white glaze is applied on top of the white glaze, which has a white carved pattern as if it were inlaid.

Red Shino

Akashino is the same technique as Nezumi-shino, but it is different from Beni-shino in that it has a reddish color instead of becoming nezumi-shino. Beni-shino is made with a clay called “akaraku” instead of oni-ita.

Neriage Shino

Neriage Shino is also called “Neriage Te-Shino,” but in terms of technique, it is better to call it “Nerikomi. It is made by kneading red clay into white clay, or vice versa.

Oribe

As the name implies, Oribe is a type of tea bowl favored by Masashige Furuta Oribe, and is called Oribe black, black Oribe, blue Oribe, red Oribe, etc. If all Oribe favorites are called Oribe, Shino must also be included in the Oribe ware category. In fact, among Shino ware, there are plates and bowls that have been handed down from generation to generation with the name “Oribe” or “Oribe” written on the box. Today, however, we generally include all white-glazed pieces in the Shino category, and call black-glazed or blue-glazed pieces Oribe.

It is not clear when the Seto tea bowls favored by Oribe began to be fired in Mino kilns. According to “Tsuda Sosho Chayu Nikki (Diary of Sosho and Tea Ceremony),” Furuta Sasuke, or Oribe, held a tea ceremony using Seto tea bowls on January 13, Tensho 13, which is the first time Oribe’s own tea ceremony was recorded in the Momoyama Tea Ceremony Chronicle. Although there is no way to know what kind of Seto tea bowl was used for that first tea party, Oribe was 42 years old at that time, and Sasuke Furuta was also appointed as Oribe-masa, the fifth highest-ranking official, at the same time Hideyoshi was appointed as Kanpaku in July. Since then, he was referred to as “Oribe” and called “Oribe-dono” or “Lord Koori. Therefore, the 13th year of Tensho was a memorable year for Oribe. Although he was a military commander, he may have already attracted attention in the tea ceremony world when he invited a great tea master like Tsuda Munenori to hold a tea ceremony. Considering that Tensho 13 is the earliest year for the use of “Seto tea bowls” (not Tenmoku) in Momoyama, it is assumed that there was already contact between Oribe and Mino potters at that time, or the tea bowl used for the party may have shown Oribe’s taste. However, the Rikyu style Chojiro tea bowls are not known to have been used. However, if it was in Tensho 14 when Chojiro tea bowls in the shape of Rikyu first appeared at a tea ceremony, Oribe’s taste may not have been born yet, and this is another future issue that should be solved by investigating the news and documents of the time.

After Sen no Rikyu died in Tensho 19, the tea ceremony world moved to the Oribe era, and in the Bunroku era, “Seto tea bowls” were almost always used in Oribe’s tea ceremonies, indicating that his relationship with Mino Seto had deepened considerably. In the Keicho period, Oribe’s preference is clearly shown here. In other words, on February 28, Keicho 4 (interestingly, the day of Sen no Rikyu’s death), he used the tea bowl called “Seto Tea Bowl Hitsumi-houya Heukemono ya” as shown above. This is a tea bowl that must have been Shino or Oribe Black or Kuro Oribe Kutsukata, and is said to be a representative style of Oribe’s taste today. In addition, “White Tea Bowl, Seto” or Shino was used in Keicho 6, and “Tea Bowl, Black Seto” was used by him in Keicho 8.

The tea bowls favored by Furuta Oribe, who was a leader of the tea ceremony, were used widely at tea ceremonies held in Ichimata, just as Raku tea bowls favored by Rikyu had been used widely in the past. Of course, it must have been the black Oribe tea bowls that were the mainstay of this boom.

According to the above, Seto tea bowls of the Oribe period were mainly examined based on tea ceremony records of the Momoyama period, and it can be inferred that the period of pottery production of Seto tea bowls was not so long ago, and that they increased rapidly almost at the same time as Chojiro ware, that is, from around Tensho 14 or 15. Therefore, it can be said that Setoguro and Shino ceramics were mostly produced in the late Tensho period or later, even though it is said that Setoguro and Shino ceramics were produced in the early Momoyama period.

Oribe Black

Although it is not known when the classification was made, the plain black glazed kutsu chawan of Oribe’s preference is called “Oribe black” instead of “black Oribe. The style of these bowls, even in the shape of a shoe, is often massive, and it can be said that a more powerful artifice was added to Seto black. It was probably fired from the end of the Tensho period to the beginning of the Bunroku and Keicho periods.

Black Oribe

This type of ware is not all black, but has a pattern in which a picture is painted with iron glaze between two layers of black glaze, and the painted area is covered with a thin layer of white glaze, or the black glaze is scraped off and the white glaze is applied to form a pattern. Most of them are thought to have been fired during the Keicho period, but some are thought to have been fired in the early period and others in the late period, and those similar to Oribe hizukuro are earlier and often thicker, such as kuchizukuri. The later works gradually lose their heaviness and become more decorative and light.

Red Oribe

Hachi Narumi Oribe, also known as Narumi Oribe, is made by joining red and white clays together, applying blue glaze to the white clay and white mud to the red clay part, and then adding iron painting lines on top of the glaze. Most of them are pots or bowls, and I have never seen any tea bowls. Red Oribe is made only from red clay, and this volume includes two bowls, one with a “Yamaji” pattern and the other with a “Suji” pattern. The firing date of these bowls was later, so to speak, when Oribe ware was ready for mass production.

Shino Oribe

At first glance, this white Shino ware with feldspar glaze appears to be Shino, but there is no fire color at all, and it is often used in large dishes, bowls, and other wares. Tea bowls are also rarely seen, but they do not have the flavor of Shino, and should be considered Shino ware that was mass-produced in a climbing kiln.

Picture Oribe

Also known as “Oribe dyed” or “white Oribe. The base is white but hard, and the white glaze is made by adding ash to feldspar, so it does not have a soft taste. It was fired in a climbing kiln at a former mansion.

In addition to the above, there are Iga Oribe and Karatsu Oribe, which are also called Oribe, but the representative Oribe in Momoyama are Oribe Black, Black Oribe, Blue Oribe, and Narumi Oribe, and many of them, especially Oribe Black and Black Oribe, are excellent in tea bowls. However, Oribe ware in the sense that it is to the taste of Furuta Oribe must of course also include Shino. And these, together with Chojiro’s tea bowls and Korai tea bowls, were the mainstay of the Momoyama tea ceremonies. In Tensho 16 (1588), Soji Yamagami, Rikyu’s senior disciple, wrote about the general trend of tea bowls at that time, “Tea bowls by category: Karachan tea bowls, Seto tea bowls, and even tea bowls of the present porcelain. Soji Yamakami’s words were a straightforward expression of such a situation. It is also impressive that Soji said, “Formality is the most important part of Sukiyotsukutsu”, and it can be said that the spirit of free style without being bound by formality was the breeding ground of the famous Momoyama bowls.

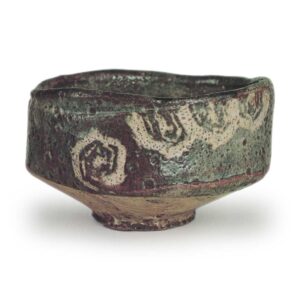

Hakuan

There are about 20 tea bowls called Hakuan that have been handed down in Japan. According to legend, the name originated from a tea bowl that belonged to Soya Hakuan, a medical officer of the Shogunate who died in 1630 at the age of 62. And the place of origin was considered to be Seto, Owari, where it was fired. Since then, this has become the prevailing theory, and Hakuan is said to be a type of Ki-Seto fired in Seto, and many boxes are marked “Seto Hakuan”, and in fact, “Honka Hakuan” has a label “Seto Hakuan Tea Bowl”, while the Hakuan inherited from the Kuroda family is marked by Enshu Kobori as “Seto Tea Bowl”. From the above, it is certain that Hakuan was regarded as two types of Seto tea bowls in the time of Kobori Enshu.

As for the date of its production, Kusama Waraaku’s “Tea Ware Meimono Zuishiki” states, “The Hakuan tea bowl is a Ki-Seto ware of the Rikyu period, and there is no older one than this one, and although they are almost all the same in shape, there are some small and large ones that do not match the style of the times. It was found in the city of Edo by a man named Soya Hakuan, and when Lord Enshu was living at that time, he had it looked at and asked for an inscription, which was named after Hakuan. It is said to have been produced in Sakai because it is an interesting tea bowl to mix and match, and is in demand by many tea masters.

However, in an article on the author at that time in “Bessho Kibei,” which is dated July 15, 1891, there is an inscription that reads, “Sohaku, a native of Kawagoe, Bushu, came to Kyoto in recent years and fired tea containers with ears, and in Bushu, he is called Hakuan,” indicating that Sohaku, who was called Hakuan, fired tea bowls. The “Bessho Kibei” is a highly valuable document, and from its description, the following hypothesis can be made.

The author Sohaku and the doctor Hakuan were not the same person, of course, but it is possible that the tea bowl that Hakuan owned was made by Sohaku, or Hakuan, and that Kobori Enshu, who saw it, knew it was by Sohaku and wrote “Seto Hakuan,” which is the same name as Hakuan the doctor, and that the world knew it was by Sohaku. Since it had the same name as that of the doctor Hakuan, it may have come to be known in the world as Hakuan’s “Hakuan” tea bowl, and this may have been the reason why it was passed down as in this poem. If we accept this hypothesis, the date of production must have been around Momoyama period, as stated in “Chawan Meimono Zushu”, and according to the legend that potters who were known at that time moved to Kyoto and went to various kilns to produce pottery, Sohaku must have been one of those potters.

The reason why I have ventured to state the above hypothesis is because I have long held the belief that Hakuan tea bowls were specially fired by a single potter from Momoyama to the early Edo period, and I may be a bit self-serving.

However, later, there were theories of kilns other than Seto, especially the theory of Korean origin by Hara Bunjiro, or the theory of Karatsu, because the wheel throwing marks are of Korean origin, different from those of Seto, and in recent years, the Seto theory is receding considerably. The reason for this is that the Seto pottery was originally produced in Hakuto. The reason is that the ten points of Hakuan’s work, which have been called the ten oaths of Hakuan since ancient times, and are considered the highlights of the work, include the following: “1 loquat color, 1 raw sea squirt, 1 stain, 1 high base, 1 high base crepe, 1 potter’s wheel, 1 kirazu clay, 1 chatame, 1 konuki milk, 1 edge-bent shape,” and “bamboo joint base, high base with flying glaze” as well as the following promises. However, when we look at the characteristics of the tea bowls themselves, such as the fact that many of these features are more common in Joseon-derived tea bowls than in Seto-derived tea bowls, and the fact that Hoeyoung ware from Joseon has a glaze exactly like that of Hakuan tea bowls, the Seto theory has to be retracted.

However, the most significant feature of Hakuan tea bowls is that many of them are consciously made with extremely sophisticated workmanship, and the one-character clay cracks on the body and the one-character sea cucumber glaze on it were consciously made and glazed. and the glaze on it was consciously made and applied. However, among Hakuan tea bowls, there are some without sea cucumber glaze at all, such as the tea bowl donated to the Tokugawa Art Museum by the Okatani family of Nagoya, and others with sea cucumber glaze on the inner surface, not on the outer surface, and even those with a promise, such as “Honka Hakuan” and “Okuda”, “Fuyuki”, and “Kuroda”, there are also some differences in the production style There is a difference between “Honka Hakuan” and “Okuda”, “Fuyuki”, “Kuroda”, etc., and there is no doubt that these tea bowls were made artificially.

Therefore, if we make a hypothesis, it is possible that there is something that is the ancestor of Hakuan (or it may have been a tea bowl from Korea) and that it was used as a model for the production of so-called “promised” tea bowls.

In conclusion, as for the place of origin, I currently believe it to be Seto or Kyo Seto. In that case, the Korean style would be an issue, but considering the fact that this was a special demand piece, it would not be so important. What is most resistant to the theory of Joseon or Karatsu origin is the fact that Kobori Enshu refers to it as “Seto Hakuan” or “Seto Tea Bowl” at a time not too far from the date of production, and the clay seems to me to be of Seto rather than Karatsu origin. Therefore, although the ancestral form may have been a Korean tea bowl (or it may have contained the ancestral form if all the Hakuan tea bowls in the transmission period are examined in detail), the Hakuan tea bowl with its well-promised shape seems to have been artificially made in a Kyoto Seto-style kiln or fired in Seto, and a Korean artisan may have been involved in its production, or As hypothesized above, it could have been in the hands of the Souhaku workshop.