Chojiro, Doyuri, Koetsu, Karatsu, Hagi, Takatori, Satsuma, Shigaraki, Asahi, Nikiyo, Kenzan

Chojiro

The Momoyama period (1568-1600) was a time of great change in the history of Japanese ceramics. Examples include the emergence of Shino and Oribe ceramics in the Seto region, which were completely different from the traditional styles, and the new Karatsu ceramics in Kyushu. Raku ware, another new ceramic art that began in the Seto period, deserves special mention for its significant influence on later Japanese ceramic art in general.

It is said that Raku pottery was started by Chojiro, followed by Tsunekei and Doyuri. However, research based on recently published ancient documents and newly discovered ceramic artifacts from the Raku family has revealed various errors in the conventional theory.

According to the Raku family’s old document, which is in the handwriting of So-iru, the fourth generation in the family history, and dated December 17, Genroku 1, the first year of the Genroku era, a person called Sokei is featured prominently alongside Chojiro.

This Sokei is said to be the same person as Sokei in the inscription above the portrait of Rikyu, said to have been painted by Hasegawa Tohaku, who is said to have been a member of the Omotesenke family. The author of the inscription is Haruya Soen, the 111th successor of Daitokuji Temple, who wrote the inscription on the fourth day of the fourth month of the fourth year of the Bunroku era, the year of our lifetime, at the request of “Rikyu’s son Sokei”.

Another example in which the name Sokei can be seen is a yellow and Ryokuyu Raku ware incense burner in the shape of a lion, with the inscription “Toshiroku 60 Tenkaichi Tanaka Sokei (Hanashii) Bunroku 2-nen September Yoshinichi” engraved on its abdomen. Since this date is the same year and month as that of the aforementioned image of Rikyu, and since the family name is Tanaka, the same as that of Rikyu, it is assumed that there is a deep connection between this incense burner and the image, or that it was made for the purpose of being used at a memorial service for Rikyu.

Based on these materials, it has been recognized that the Raku ware series of the Chojiro period can be constructed as follows.

Thus, the direct line of Chojiro died out in the next generation, but the line of Sokei continued, so it can be easily imagined from this line that Raku ware was developed by the descendants of Sokei, and that the bowls now known as Chojiro include the works of the first and second generations of Chojiro, Sokei, Soumai, Tsunekei and others, Therefore, it can be said that Chojiro ware is a generic name for them.

One of the examples of Raku ware produced by Chojiro I is a lion with a dull yellow glaze. The lion, standing on its head, is said to have been a model for the tomekabawara tiles that adorn the lower ridge of the roof, but its grandiose style reveals extraordinary formative ability. The abdomen is inscribed “Tensho 2-spring, Yorimei Chojiro made,” which clearly indicates the date of production, but the presence of such a model of a tome cover tile suggests that Chojiro was originally a craftsman related to tile making. However, his country of origin is not certain, being said to be either China or Korea. The glaze on this lion-shaped tile is lead glaze and yellow, which supports Koetsu’s theory that Chojiro’s country of origin was China.

In Korea, lead glaze was used from the Silla period to the early Goryeo period, but not during the Yi Dynasty, which corresponds to the Momoyama period. In addition, the glaze color was limited to coppery green. In China, lead glaze has been used since the Han Dynasty, and this trend continued until the Qing Dynasty of the modern era. The lead-glazed ceramics of the Qing Dynasty are the so-called Koji ware, which differs from Korean ware in the use of yellowish and purple glaze colors along with green. As is well known, Raku ware is mostly black and red, but the red Raku glaze is the same as the yellow of Koji ware, and therefore Raku ware is thought to have originated in China. This is an indication that Chojiro was of Chinese descent.

The year Tensho 2 inscribed on this tome cover tile is two years before Oda Nobunaga completed construction of the castle in Azuchi. According to the “Nobunaga Kouki,” the roof tiles for this castle were made under the supervision of a Chinese architect, Ichikan. It is possible that Chojiro’s nationality being the same as Ikkan’s and his occupation being a tile maker, the construction of the Azuchi Castle may have been an opportunity for him to connect with Ikkan, leading to the production of these tome cover tiles.

The examples of early Raku ware represented by Chojiro include the aforementioned lion-shaped tome cover tiles and incense burners, as well as incense burners and plates, but these are rare, and the majority of the pieces are tea bowls.

They were called “Imayaki chawan,” “Kuroyaki chawan,” “Kurochawan,” or “Yaki-chawan,” but it cannot be said that all of them were Raku chawan. Looking at the tea ceremony records of Hisamasa Matsuya, there is “Imayaki tea bowl” on September 14, Tensho 16, “Imayaki black tea bowl” on September 18, “Yaki tea bowl” on October 16, and “Kuroyaki tea bowl” on November 14, and “Shimasushi black tea bowl” is also found in the “Nanbouroku”. The fact that these different names are given to tea bowls used for tea ceremonies only a few days apart suggests that they were not identical. However, there is no great doubt that the majority of the bowls other than the “Ima-yaki Tea Bowl” were made by Raku ware.

The name “Ima-yaki tea bowl” appears in the “Matsuya Kaikki” at the end of Tensho 14, and often appears until the middle of Tensho 16, and “Ima-yaki Kuro-chawan” is mentioned only in September of the same year. As is well known, Raku tea bowls come in red and black, but the record does not indicate whether the Imayaki tea bowl that first appeared in the “Matsuya Kaikki” was red or black. However, in the “Tsuda Munenori Diary,” the name “red tea bowl” is mentioned more than ten times from its first appearance on February 1, Tensho 9 until Tensho 11, and in the diary of Imai Munehisa, “tea bowl wood keeper” is mentioned in Tensho 11. Considering the fact that the glaze of the aforementioned tome cover tile, which is the oldest example of Raku ware, is red, it is assumed that the red tea bowl that appeared from Tensho 9 was a Raku tea bowl of the present ware. Therefore, it can be said that the red Raku tea bowl was born prior to the black one.

This red tea bowl is thought to have been especially close to Sorinoe. This red tea bowl was first used at a party to which Rikyu, Souji Yamagami, and Soyasu Bandaiya, who are thought to have been especially close to Munenori, were invited. In addition, at a meeting held on November 25, Tensho 10, when Muneo invited Haruya Soen of Daitokuji Temple, the main guest, Soen, was served with an ashikatenmoku, but his companions were served with a red tea bowl and a sprinkled tea bowl. From these examples of use, it can be inferred that the red tea bowl was rarely used for formal gatherings. On September 10, Tensho 18, Kamiya Sotan, who was invited to Rikyu’s tea ceremony at Juraku-dai, wrote in his “Sotan Diary” that Rikyu said, “Kuroki ni chatatekudo koto kami-sama gokirai kudo hodoni ……”. Koetsu says that Hideyoshi had a flamboyant taste, and that the tea ceremonies of the time were flamboyant in imitation of him. Therefore, the flashy red tea bowls that began in Tensho 9 must be seen in many subsequent tea ceremonies. However, such examples are very rare, probably because the red tea bowls were not suitable for tea ceremonies.

However, there were some excellent red tea bowls, such as the “Hayabune” bowl, which is said to have been fought over by Ujisato Gamo and Tadaoki Hosokawa. In one of Rikyu’s letters to Yamato Dainagon Hidenaga, he inquired, “Two of your tea bowls are ready now, and I would like to ask you to make them again…” Another letter to Seta Sobe, one of the seven philosophers under Rikyu, was also written, “…The red tea bowl is very beautiful and I will make it again within the next two years. It can be inferred that the interest in red tea bowls was quite deep among the prominent sukiya of the time. The fact that black tea bowls are often mentioned in the Kaikki may be due to the fact that black was preferred for the tea ceremony, which was based on the concept of “wabi-yobi,” or it may be a result of the fact that the firing of red tea bowls was not yet mature enough to produce a fine product suitable for tea ceremony.

Yamakami Soji, a well-known tea master of the Tensho period, wrote, “Souji tea bowls are Tang-style tea bowls, Korai-style tea bowls, Seto-style tea bowls, and Kon ware tea bowls…” He listed his preference for tea bowls around Tensho 16. The Korai tea bowls of the time include “Hira-taki Korai Tea Bowl,” “White Korai Tea Bowl,” “Black Korai Tea Bowl,” and “Ima Korai Tea Bowl,” as well as “Ido Tea Bowl. The Korai tea bowls called “Shiroki,” “Kuroki,” and “Kon” are not well known, but many of the well tea bowls have been handed down to the present, so it is clear. It is also possible to assume the approximate shape of the “flat taki Korai tea bowl”. It is very easy to imagine that the shape and glaze color of the Koryo tea bowls that were popular at that time were imitated in the tea bowls of today’s pottery, and the red tea bowls with “Goto” and “Dojoji” inscriptions are thought to be equivalent to them.

In addition, the “Matsuya Kaikki” mentions that the tea bowl used for the morning tea ceremony held on October 13, Tensho 14, by Nakabo Gengo – Inoue Takakiyo, a deputy governor of Nara – was a “Soyei-shaped tea bowl”.

Raku tea bowls called Chojiro were made by several people, as mentioned above, and one of them, Sokei, had a special relationship with Rikyu, who would have ordered the firing of tea bowls of his preferred shape or those requested by others from the Chojiro family. This Soyei preference is not known, but it can be seen in a few examples,

I have been thinking about it a lot, but I have not heard of it. I am going to send a large boat to Shoan, which will be a great inconvenience for me.

Both three men are coming.

This is a letter by Rikyu attached to Hayabune.

This tea bowl inscribed “Hayabune” and “Daikoku” seems to have been Rikyu’s favorite shape and glaze color, since it is understood from the meaning of the letter on the right that this was the tea bowl that Rikyu loved and respected the most. Therefore, it can be said that “Toyobo”, “Ayame”, “Muichimono”, “Kimori”, etc., which show a similar style to this Hayabune, were one of the types favored by Rikyu. In addition, “Kitano”, “Kurocha-bowl”, “Tarobo”, and “Jiro-bo”, which are tea bowls similar to “Daikoku”, are also so-called Soyo-shaped tea bowls favored by Rikyu.

Another example of Rikyu’s unique taste is the tea bowl named “Mukiguri”. This Masu-shaped tea bowl is said to have been modeled after a Shiho kettle by Kojoji, which is said to have been Rikyu’s favorite, and is the only other example of Rikyu’s preference.

Doyuri

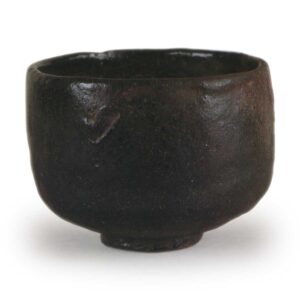

Early Raku ware tea bowls, represented by “Chojiro,” are simple in appearance and rich in what is called “wabi” taste. However, in the Raku tea bowls of the early Edo period, the shadow of wabi, which can be said to be an intrinsic beauty, faded away, and the flamboyance became remarkable, and the beauty was shown on the outside surface. Therefore, the works of Doyuri, which represent the Raku tea bowls of this period, are in sharp contrast to the style of Chojiro ware tea bowls.

As Hon’ami Koetsu praised, “The present Kichibei is a master of Raku, and the work of Kichibei’s successor should be treasured. …… He is said to have died on February 23, Meireki 2, at the age of fifty-eight. There is another theory that he was 83 years old, but considering his grandfather’s age, this theory has little validity. According to the genealogy of the Raku family, Doyuri is listed as the third generation, but if we trace the lineage from the beginning of Raku pottery from Chojiro to Chojiro II to Soumai to Soukei, we arrive at five generations. The reason why the “Manpo-Zensho” lists Doyuri as the fifth generation may be based on the history of Raku ware.

From the end of the Genna period to around the Shoho period, when Doyuri was active, the pottery industry in Kyoto seems to have been dominated by the firing of soft ceramics, and Yasaka, Awataguchi, and Oshikoji are listed as kiln sites for this purpose.

In the diary of the monk Horin of Rokuon-ji Temple (died August 28, 1768, age 76), in the first year of the Shoho era, Funakoshi Sotoki, a retainer of Hojo Kyutayu, the governor of Kawachi Province, gave a wisteria-shaped incense container to the priest on his departure to Kyoto. This incense container was made by Seibei, a potter in Yasaka, and was made in a mixture of blue and purple. Hourin also visited Seibei’s workshop in Yasaka, guided by Ohira Gohei, a tool merchant who often visited him, and observed how Seibei made tea containers, incense burners, and incense containers on the potter’s wheel. From this example, we know that pottery in Kyoto at that time was also fired in Yasaka, and we can imagine that the glaze of wisteria-shaped incense containers made by Seibei’s kiln was similar to that of kojito-type pottery, However, it is noteworthy that the bowl is referred to as “Ima-yaki. In addition, the ume (plum) glazed bowl presented by Ohira Gohei, who visited Horin on New Year’s Day in the fifth year of the Shoho Era to express his greetings, was also distinguished from the lid and described as “Ima-yaki” ware, along with the Yasaka-yaki gotoku lid and rest. From these examples, it can be inferred that the blue-glazed bowls and plum-painted bowls presented to Horin were not fired at the Seibei kiln, but were Raku ware, which was called “Ima-yaki” at that time.

In a tea ceremony account written by Hisashige Matsuya in 14 Kan’ei, there is a reference to a “red tea bowl of Shuraku ware,” so it seems that Raku ware was also called Juraku ware by some people. However, Raku ware was generally known as Imayaki.

Just as it is said that Rikyu’s guidance was a major influence on Chojiro ware, it is said that Doyuri also received guidance from Sen Sotan. However, in his works, he did not use words to describe the figure, which is called Soyei-shiki. It is well known that Doyiri’s alias is called “NONKOU.

The origin of this alias is that Sotan Sen made a double-cut bamboo flower vase and gave it to Douiri with the local name “NONKOU” when he visited the Noko teahouse in Nojiri, Kanbe Village, Suzuka County, Ise (now Noki-cho Nojiri, Kameyama City). Later, when Sotan visited Douiri, he said, “I am going to NONKOU’s place,” and that is how “NONKOU” became Douiri’s alias, according to Eisaku Oda. This legend suggests that Dairi was patronized by Sotan. The fact that a red tea bowl named “Horin” by Doyuri, which is said to have been a treasure of the Sen family and later passed down to the Matsudaira family of the Izumo Matsue domain, was presented to the monk Horin of Rokuonji, a leading member of the court nobility at the time, with the advice of Sotan, also confirms the relationship between Sotan and Doyuri. The fact that Soton borrowed money from Hourin suggests that Soton was not in a very rich financial situation. Therefore, Sotan’s support for Doyuri was probably not large financially. Koetsu’s comment, “A master is always poor,” indicates a part of the situation during this period.

Doyiri also received a lot of guidance from Koetsu. The original meaning of Douiri’s alias “NONKOU” was “strict wood of budding trees,” a corrupted form of an old Japanese word used in the back of Japan, and Kikuoka’s theory that Koetsu, who was fond of Douiri, began to use the word may be due to the close relationship between Koetsu and Douiri.

As can be seen from the fact that Koetsu says, “…… we have given Kichibei the transmission of medicines and other things, and we are going to bake them for comfort. What is particularly striking is the fact that the glaze color is very shiny. The reason for this is said to be that the structure of the Raku family kilns changed around that time, and extremely high fire power came to be used. It is also said that this is the reason why Koetsu tea bowls have many cracks in the kiln. However, there are no cracks in the kiln in Doyuri tea bowls. This is thought to indicate the difference in pottery making between an expert and an amateur, born from the difference in the degree of fineness and coarseness of the kneading of the clay. On the other hand, it is thought that Douiri, who was an expert, would not have allowed such a tea bowl, which is considered to be a failure in firing, to be released to the world. This may be the reason why we do not see any tea bowls with cracks in the kiln among the examples left by Douiri.

Like those of Chojiro and Koetsu, there are seven famous tea bowls by Doyuri, and they are called the seven types of nonkou. These include black tea bowls inscribed “Masu,” “Chidori,” “Inazuma,” and “Shishi,” and red tea bowls named “Horin,” “Wakayama,” and “Tsuru. Some of them, such as the “Masu” bowl, have an unusual shape with a stroked horn body, which was not seen in Raku tea bowls until then, but the general appearance is relatively mild and not too eccentric like the later Raku tea bowls. Therefore, compared to the appearance of Koetsu tea bowls, there is a sense that they are less free and unrestrained. This is also probably due to the position of the tea bowls made by the experts as well as the cracks in the kiln. However, the thinness of the body, the tension in the curved surface of the body, and the wide inner surface, so-called, the broadness of the body, show Douiri’s extraordinary formative ability.

As described above, the teacups of Doyuri do not show the same changes as those of Koetsu’s teacups in terms of form, but the glazes are much more varied than those of Koetsu’s. One of them is that the body is curved from the end of the mouth to the end of the body. One of them is the use of the so-called “curtain glaze,” in which the glaze tone from the mouth edge to the body side is like a hanging curtain. This glaze tone is a new invention of Doyuri, and is a manifestation of a technique not seen in Raku tea bowls before Doyuri. The vermilion glaze, in which various colors are dotted among the glossy black glaze, is also from Doyuri tea bowls, and the glaze surface of the black glaze emits light like the wings of a jewel beetle, also from Doyuri tea bowls. The luster similar to that of jewel beetle wings is said to appear due to the thicker glaze layer, as in the case of makume glaze. What is also noteworthy about Doyuri tea bowls is the use of white glaze, as shown in the “Shishi” inscribed bowl, one of the seven types of NONKOU. The white glaze may be applied in a so-called one-sided replacement style, as in the “Shishi” inscribed tea bowl, or in an abstract pattern, as in the “Zan’yuki” inscribed tea bowl, or in a brush pattern.

The above-mentioned “Imayaki” tea bowl is marked with a picture of plum blossoms, which was probably painted in white. An Akoda-shaped incense burner was found in the grave of the second Tokugawa Shogun, Hidetada Tokugawa, and its glaze is white and its mark is the Jokei mark. However, the white glaze was only used to cover the surface of the bowl, and was not used for pictorial patterns, as seen on doiri tea bowls. Therefore, it can be said that this was also a new conception of Doyuri. This can be considered as a manifestation of the influence of the interest in pottery at that time, which was leaning toward so-called “painted ware”. In addition, there are also some Doyuri tea bowls with a new innovation, so-called “sunaguri,” in which the glaze surface has a rough, coarse texture like that of the unglazed clay.

The seal is usually stamped on the back of the bowl’s pedestal with the so-called “Jiraku” seal, in which the “white” between the “ito” of the character for “Raku” becomes “ji” (自). However, there is also an unusual case, such as a black tea bowl inscribed “Sanko”, where the seal is stamped on the border between the body and the waist, as a kind of decoration. This typeface seal in which the “white” becomes “ji” is also used in the works of Soukei, Joukei, and the ninth generation Ryouto, but in the Douiri, the “ito” on the left is different, as if it were a “nom”. It is said that the reason why Doyuri has the alias “NONKOU” is because of this “nom”.

Koetsu

Raku ware, founded by Chojiro at the beginning of the Momoyama period (1573-1600), was succeeded by the descendants of Tanaka Sokei, whose family was the birthplace of Chojiro II’s wife, and was used exclusively for firing tea utensils. Meanwhile, as the tea ceremony flourished, people related to the Raku family, such as Yahei Tamamizu, and others with no connection to the Raku family tried their hand at Raku ware, either for a living or as an extra skill. As a result, the Raku family’s pottery was often referred to as hon-gama (main kiln) and others as waki-gama (side kiln). Among the many side kilns, the Raku tea bowls made by Hon’ami Koetsu, whose family profession was sword polishing, were widely known and highly regarded from early on.

Koetsu was a master calligrapher who, together with Gosuioin and Shokado Shoujyo, was known as one of the “Three Brushes of the Kan’ei Era. It is said that when someone asked Koetsu who was the first of the three brush strokes in the Kanei era, Koetsu bent down his finger and said, “……” and gave his own name. He was also very proud of making Rakuyaki pottery, as seen in his statement, “I am better than Shokado in making pottery. ……

Koetsu said, “I have prepared the pottery from time to time using the good soil of Takagamine (……),” which suggests that he mainly used the soil of Takagamine in northern Rakuhoku, where he lived in hiding. However, there is also a letter to Kichizaemon stating, “I have about a quarter of white clay and red clay, so you can leave at your earliest convenience. ……” This suggests that he also used clay from outside Takagamine. Furthermore, the letter to Kichizaemon, in which he asks for the glaze by saying, “The tea bowl is ready ……,” and “This tea bowl is ready to be glazed ……,” suggests that the clay was made at his residence in Takagamine, which was a craft village, and that the glazing and firing were done at his house in Takagamine, which was also a craft village. It can be inferred that the glazing and firing were commissioned exclusively to Kichizaemon, a Raku ware potter. In addition, Koetsu declared his entrance into the art of Raku by saying, “The current Kichizaemon is an expert in the art of Raku (……).” The address Kichizaemon given in these notes is probably that of Tsunekei.

Therefore, Koetsu and Tsunekei were very close friends, and it can be said that they were “able to go out at a moment’s notice. Jokei died in the 12th year of Kan’ei Era, and Koetsu died later in the 14th year, so their relationship must have started early. Koetsu was very close to the Tokugawa clan, as Ieyasu gave him Takagamine in the first year of the Genna era. The discovery of an incense burner made by Tsunekei in the tomb of the second shogun, Hidetada, is not an oddity when one considers the relationship between the Tokugawa family and Tsunekei, with Koetsu at the center.

Thus, Koetsu tea bowls made with the help of Kichizaemon Tsunekei of the Raku family and Kibei Douri were of deep interest to the public at the time, and therefore, it is said that many Gonmon and Kiken were commissioned to make ceramics for the Tokugawa family. In a letter to Kato Shikibu Shosuke Akinari, lord of the castle in Iyo Matsuyama, Koetsu wrote, “…the bowl you asked me to make, Mr. Samasuke, is almost finished…and was presented to you the other day. However, Koetsu had a high collar, saying, “I have no intention of making a name for myself in pottery,” or “I do not want to be a family business,” and his tea bowls were made by hand, so it is thought that the number of tea bowls made was small, and therefore, those that have been handed down are extremely rare.

The tea bowls that have been handed down and are said to have been made by Koetsu include a black and white one-sided tea bowl inscribed “Fujisan” with Koetsu’s handwriting and seal on the box, black tea bowls such as “Amegumo”, “Shigure”, and “Kugai”, and red tea bowls inscribed “Kaga”, “Bishamondo”, “Shoji”, and “Yukimine”. Also, the white glazed “Ariake” is also famous for its different glazed tea bowls.

The beauty commonly found in these Koetsu teabowls is beyond description.

In particular, they are the vastness and elegance of their air, the triumph of their appearance that seems larger than the actual size, and the simple yet complex color tones. These characteristics can already be seen in Chojiro ware, so it can be said that this was one of the styles of the period. However, what is particularly striking compared to Chojiro ware is that Koetsu was a member of the wealthy Hon’ami family, but his life was extremely humble, as can be seen from the following words: “Koetsu had many special characteristics, but he had a hard time learning, and from the age of 20 until he reached his 80th birthday, he lived alone with only one small person and a small bowl of rice. Koetsu’s life was extremely modest. In a letter of opinion submitted to Matsudaira Nobutsuna, Koetsu requested tolerance, saying, “For the government of the country, it is good to wash heavy boxes with surikogi. It can be said that such a personality of Koetsu was expressed in the tea bowl as the above-mentioned taste.

Looking at the Koetsu teacups from the viewpoint of style, they can be roughly classified into three categories. In Japanese calligraphy, the three types of calligraphy can be compared to the differences between “true,” “action,” and “grass.” “Fujisan” and “Kaga” can be placed in the “true” category, “Shigure,” “Bishamondou,” and “Rain Cloud” in the “action” category, and “Yukimine” and “Otogozen” in the “grass” category.

The bowls listed in the “Shin” category are upright in shape like a sheer rock on the body side, and the border between the body and the waist is angular and clearly distinguished, with a flattened surface from the waist to the base. The height is extremely low and small, and is warped to resemble an irregular polygon, reminiscent of a thinly sliced bamboo ring. Although there are few examples of this type of elevation in Chojiro ware, a glimpse of it can be seen in the red tea bowl “Goto” and the black tea bowl “Touyoubou”, so it is thought that Koetsu tea bowls were influenced by Chojiro ware. It is likely that the tea bowls made by Koetsu and Kosaika were influenced by this style of high stand making, as Konoike Michikazu, a tea master and connoisseur from Genroku to Kyoho period, said that many of the tea bowls known as Chojiro ware were mixed with those made by Koetsu and Kosaika.

The “Fujisan,” “Kaga,” and “Shichisato” types, which fall into this “true” category, are characterized by many spatula marks, which are especially noticeable on the sides. This type of work style is not seen in Chojiro ware at all, so it can be said to be unique to Koetsu tea bowls.

The next Koetsu teabowl listed as a “Gyo” category also has the same upright body side as “Fujisan” and others. However, the chamfered spatula is rarely seen. In addition, the surface that moves from the body to the waist is gently curved, so it is difficult to clearly distinguish the border between the body and the waist. The style of this body and waist is similar to that of “Daikoku” of Chojiro ware, so it can be assumed that it is following the style of “Daikoku” style. The height of this type of bowl is also low and small, and the lack of a kabukin-like convexity in the center is also the same as the height of the “Shin” bowl. Furthermore, there is also an example such as the “Ameun” tea bowl, which has no boundary between the back of the bowl and the top of the bowl and is similar to the bottom of the go-ceremony chest.

The next type of “grass” is the style seen in red tea bowls such as “Seppo”, “Otogozen”, “Kamiya” and so on. These are the most elegant of Koetsu teabowls, showing a style full of wildness, and if we consider the “Shin” type to be a dignified appearance with a collar, this is a relaxed form in a yukata. Therefore, the appearance of this type of teacup is deeply familiar.

The height of “Otogozen” is lower than the surface of the waist, so that it looks as if there is no height at first glance, and the so-called “thrust-up” bottom of the bowl gives us a strong impression of this. In addition, it is said that this type of Koetsu teabowl is the most superior in terms of tactility, which is said to be one of the characteristics of Raku teabowls suitable for tea ceremonies.

This kind of odd shape is often seen in Oribe ceramics. In Koetsu’s letter to Shikibu Shosuke Kato, the name of Oribe Furuta can be seen: “Yesterday I saw your card…I would like to make a tea ceremony, but Oribe-dono Goshita-jikata ha no ha …….” Also, Shaomasu Haiya, who was close to Koetsu, wrote: “I am Mochitoku-sai, one of Hon’ami’s friends, He was a student of both Oribe and Oda Yuraku, and as he visited both their houses (Oribe and Yuraku) frequently over the years, he was always making improvements, and both places were very fond of him. Therefore, it is assumed that the warped appearance of the tea bowls and bowls was influenced by Oribe’s tea ceremony. As for the “Fujisan”-shaped tea bowls with the chamfered style mentioned above, when we consider that the Goshomaru tea bowl called “Furuta Korai” was owned by Oribe, it is understood that it was not born by chance.

The glaze color of these Koetsu teabowls has in common that the color is vivid and glossy. As mentioned above, Koetsu commissioned Kichizaemon to fire his own tea bowls, so the fact that many Koetsu tea bowls have such glaze colors suggests that the Raku family’s Raku firing method had undergone a major change by this time. The fact that many cracks in the clay of tea bowls such as “Amegumo,” “Shoji,” and “Seppo” indicate that they were fired at a high firing temperature, and the glaze color gloss may also have been produced as a result of the same high firing power.

In this way, Koetsu Tea Bowl shows many characteristics not seen in Chojiro ware, but to summarize its taste, it is remarkable for its individuality. As mentioned before, Chojiro ware was born from a small cottage industry, so to speak, created by Chojiro and a few members of the Sokei school. Therefore, these Chojiro potteries were not filled with individuality and resulted in the firing of uncharacteristic pieces. However, when Raku tea bowls are made by a person blessed with artistic talent such as Koetsu, it is natural that the formative characteristics of Raku ware are best demonstrated, and the high evaluation of Koetsu tea bowls is probably due to such a point.

In addition, most Koetsu tea bowls weigh around 375 grams, with “Fujisan” and “Otogozen” weighing approximately 370 grams, “Amegumo” 350 grams, and “Shigure” 378 grams. These weights seem to be the scale of the bowls, which are neither heavy nor light when placed on the palm of the hand to drink tea. Therefore, it can be said that Koetsu took such factors into consideration when making his tea bowls.

Karatsu, Takatori, and Satsuma

It is well known that the pottery industry in the Kyushu region was founded by the local potters who accompanied the generals who went to war in the Joseon Dynasty during the Bunroku and Keicho periods, which were planned by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, on their return to Japan. Among them, the pottery of the Hizen Karatsu region was especially famous, as “karatsu” was a synonym for pottery.

The first time the name “karatsu” ware appears in records is when Hisashige Matsuya, a lacquer craftsman from Nara, was invited to a tea ceremony by Sen Doan in Kyoto in October of the 8th year of the Keicho Era, and was reported to have used a “karatsu mizushi” at the ceremony. In February of the same year, “karatsu mizusashi” and “shurakkuyaki tea wan” were used at a tea ceremony held by Sen Sodan, and in March of the same year, “karatsu mizusashi” and “imayaki black tea wan” were used at a tea ceremony held at Shomyoji Temple in Nara. From this example, it can be inferred that it was during the middle of the Keicho period that the name Karatsu ware finally became known to the world. Hisashige’s tea ceremony memorandum mentions that “Higo ware tea wan” was used at a tea ceremony held by Kinya Okudaira in December 1728, “Chikuzen ware tea caddy” at a tea ceremony held by Sakyo Nakanuma in January 1728, and “Tsurunoar Kokurayaki water jar” at a ceremony held by Miyake Baikyo in Kyoto in March 1828. It also mentions that a “Satsukuma-yaki tea caddy” was used at a tea ceremony held in Kyoto in May of the 14th year of Kan’ei Era (1454) by Karamono-ya Domai. This Higo ware is probably Yatsushiro ware, but it is said that Hosokawa Tadaoki invited Ueno Kizo, who had been involved in Ueno ware in Toyozen, to open a kiln in Naraki, Takada-go, Yatsushiro-gun, Higo in the 10th year of Kan’ei Era, so Higo ware mentioned in the Kyushige Kaikki is thought to have been the predecessor of Yatsushiro ware. Chikuzen-yaki refers to Takatori-yaki, which started when Nagamasa Kuroda ordered the potter Yazan (later Hachizo) to open a kiln at the foot of Mount Takatori around Keicho 5, when the country was transferred from Buzen to Chikuzen. Takatori ware was moved to Iso (Nogata City), Yamada (Kamiyamada, Yamada City), Shirahatazan (Yukibukuro, Iizuka City), Koishiwara (Asakura County), etc., but around the Kan’ei period, it was fired at the Shirahatazan kiln, and the tea container shown in the Kyushige Kaikki was probably made at that kiln. It is well known that Takatori ware is one of the seven kilns selected by Enshu Kobori, and it is said that the tea containers produced at Shirahatazan were of extremely elaborate workmanship, with the inside glazed as well. Therefore, we can imagine that Hisashige’s tea utensils would have been of the same type. Ogura-yaki is thought to have been Ueno ware from Buzen Province, and the fact that the names of Higo, Chikuzen, and Ogura-yaki, which are in the same lineage as Karatsu-yaki, appear more than 20 years later than Karatsu-yaki, indicates that Karatsu-yaki is representative of Korean pottery art.

Karatsuyaki was originally mainly used to make containers for the daily life of the people of the time. Therefore, the water jars and tea bowls mentioned in the above-mentioned “Matsuya Kai-Ki” must have been what is called “fittings” that were selected as tea utensils from among the miscellaneous utensils by a sukiya of the time, and the ko-karatsu tea bowls without any artifice, such as those called “Okukorai”, “Tobikiri” and “Negiri”, are equivalent to them. It is also possible that the blue-tinged black

In addition, the wide top and bottom sides and narrow body of the so-called black Karatsu tea bowls with bluish black glaze, which are often seen, suggest that they were not simply made as daily-use vessels, but that an artifice of the tea ceremony was added.

Hisashige Matsuya, who was invited to Hosokawa Sansai’s tea ceremony held in Yoshida, Kyoto in April 17 Kan’ei, wrote that “Higo Yaki Tea Wan” and “Ogura Yaki Water Jar” were used, and also illustrated that the water jar was in “ku” form. This shape is often seen in Iga ware and Bizen ware, both of which are said to have been fired in the early Edo period, and was apparently one of the preferred shapes of mizusashi at that time. The fact that this form is shown in Ogura ware, which is sister to Karatsu ware in terms of lineage, suggests that around the Kan’ei period, Karatsu ware, which until then had been mainly miscellaneous ware, was also producing kiln furniture in the style of tea ceremony utensils. The aforementioned black Karatsu tea bowls are also a manifestation of this trend.

Also shown in the above-mentioned tea ceremony of Hosokawa Sansai is a small bowl in the shape of a half-open bellflower, so-called “Warizan-kiji,” with an Ogura-yaki pouring vessel attached. This type of mukozuke, called Karatsu ware, was highly prized by tea masters from early times. However, no similar pieces have been found at the site of the ancient Karatsu kiln, which has now been widely investigated, and the fact that the same type of pottery was found at the site of the Ueno kiln in Bizen, a sister kiln, and that it is listed as Ogura ware in the Hisashige Kaikki, shows that the description of the kiln site in the past was right on the mark.

It is said that the fact that this type of Karatsu pottery has a tea ceremony style is largely due to the guidance of Furuta Oribe Shigenori, who died in the first year of the Genna Era at the age of 70. In a letter written by Hideyoshi to his wife, Kita Masajo, while he was staying at Nagoya in Hizen, he wrote

It is not as cold as in the middle of winter, but easier to be at ease.

The above text suggests that Hideyoshi often hosted tea ceremonies to relieve his boredom. It is assumed that Oribe, who was at Nagoya for about a year and a half from March of the first year of Bunroku, served as Hideyoshi’s tea master, and it is said that it is under his guidance that Karatsu ceramics have the appearance of Oribe’s taste. However, in the memorandum of Hisayoshi Matsuya, who attended several tea ceremonies held by Oribe between Keicho I and IX, it is mentioned that tea bowls and water jars from Seto, Imatakarai tea bowls, Shigaraki ware water jars, and Bizen ware water jars were used, but the name of Karatsu ware is not mentioned. As is well known, Oribe was a leader in the tea ceremony after the death of Rikyu, as is stated in the “Sunpu Ki” (Sunpu Ki), “Oribe was the master of Sukiyaki at that time and was greatly revered by the shogunate. Therefore, if Karatsu ware with an almost eccentric appearance, such as the Ogura-yaki water jar mentioned above, had been produced under his leadership, it is likely that they would have been used in Oribe’s tea ceremonies. However, no such examples have been found, probably because Karatsu ceramics to Oribe’s liking had not yet been fired during the Keicho period. Therefore, it is assumed that the Karatsu mizusashi presented by Hisashige Matsuya at a tea ceremony in Keicho 8 was also a “sample”. Next, the most notable example of Karatsu ware with a strong tea ceremony style is a tea bowl with an angular shape. This shape is similar to the Seto black tea bowls fired in the Higashi-Mino area around the Keicho period, and has a low base.

In addition, some of them are made with a double height, so-called “double height,” and the thick white feldspar glaze is very similar to Shino pottery also produced in Higashi-Minô.

These points suggest that Karatsu ware was closely related to Seto ware. A Karatsu ware plate is inscribed with an inscription, “Dokkoku lotus flower leakage by Enko,” which relates the legend that Keien, one of the Three Laughs of Torakkei, planted twelve lotus plants in the mountain to measure time, and knew the time by the reflection of the lotus on the surface of the water. This article is also found in Shino pottery, which indicates the linkage between Karatsu and Seto.

The remains of more than 120 kiln sites of Karatsu ceramics have been discovered, and they are classified into the Kishidake, Matsuura, Taku, Takeo, and Hirado lines. The Kishidake lineage includes the Hobashira and Iidora kilns in Kitahata Village, Higashimatsuura County, Saga Prefecture, and the Donoya kiln in Sochi Town, Saga Prefecture. The blue sea wave patterns that often appear on the inner surfaces of jars fired in the Iidong kilns, which are the result of the so-called “beating technique,” are a clear indication of the lineage of Karatsu ceramics, since this method of forming is a technique of Korean ceramics. The Matsuura lineage includes the Fuji no Kawauchi Kiln in Imari City, which produced so-called Joseon karatsu, which resembled the style of Joseon ceramics by using a single color of ame-iro glaze or adding a cloudy white glaze to it, and the Doen Kiln, which produced elegant, so-called ekaratsu, in which painted patterns were drawn with black or conscientious glazes. The Taku kiln is said to have been started by the pottery school of Lee Sampei, a naturalized potter who followed Taku Jun’an, a retainer of the Nabeshima clan, and is known as the Koraidani kiln in Nishitaku-cho, Taku City, Saga Prefecture. Takeo kilns were also established by the Soden school of potters who followed Ienobu Goto, a retainer of the Nabeshima clan, and became naturalized citizens of Japan.

The Hirado school also includes the Kiharayama Kiln in Oriose, Sasebo City, Nagasaki Prefecture, which is known for its skillful use of brush marks.

Karatsu ware, which is called Ko-Karatsu and belongs to the Kishidake and Matsuura lineages, is generally made without water straining because the Karatsu clay is generally rough but has uniform particles, as is called “suname,” or “sandy grain. Because of the high iron content, the color of the clay skin after firing is generally dark brown or blackish brown, but some pottery made at the Matsuura kilns of Doen, Afoya, and Fuji’s Kawauchi kilns is grayish white. There are three main types of glazes: those made from wood ash left in the kiln, those made from a mixture of ash and feldspar, and iron black glazes.

Wood ash glazes are highly transparent, and depending on the difference between oxidizing and reducing flames, they can be yellowish yellow karatsu, or blue-green, which is called ao karatsu. The ash and feldspar glaze is generally opaque white, called “speckled karatsu,” and is used in many examples made by the Hozashira kiln.

Since this glaze tone is similar to that of the Huining kiln in Beisan, it is said that the Huining kiln also has a tradition in Dangjin ceramics.

The next type of glaze, tenmoku glaze, is widely used in Karatsu ware kilns, but it shows differences in color, becoming black or changing to an iron cast color, depending on the amount of iron contained in the glaze and the nature of the flame.

Hagi

Hagi ware, like the Kyushu kilns represented by Karatsu ware, is also of Korean origin. According to legend, it is said to have been created by naturalized Korean potter Ri Kei, during the reign of Mori Terumoto, in a warehouse in Matsumoto Village under Hagi Castle, or by Ri Kei’s elder brother, Ri Kuwang. However, since Terumoto entered Hagi in Keicho 9, the date of establishment must have been later.

In 1791, he was given a seal of the clan’s name, which he changed to Koryozaemon, and he became the grandson of Koryozaemon. Shinbei Tadasun, a grandson of Koraizaemon, started the kiln business on Koutake (Mt. Tangen), which his grandfather had been allowed to cut down for fuel for the kiln.

The Karajinzan area was entrusted to my father, Shinbei, who was in charge of the Fukugikisama estate.

The situation was as follows. However, the clan provided him with a small amount of rice (7 koku 6to, rice for three people), and he continued to make pottery, albeit at a slower pace.

Meanwhile, Yamamura Heishiro Mitsutoshi, a grandson of Yi Shakuwang – who later became Sakakura – and Kurasaki Gorozaemon, a disciple of Shakuwang, moved to Sanose, Fukagawa Town, Otsu County, where Shakuwang is said to have died, and established a kiln.

The biography of Shinbei Mitsumasa, the father of Heishiro Mitsutoshi, describes the opening of the Fukagawa kiln in a manuscript dated after the 9th year of the Kyoho era (Kyoho 9),

On the seventh day of the seventh month of the third year of the Meireki era, a letter of request was sent to Yamamura Shoan from six potters.

In addition, there is also a note that reads In addition, a letter of request from Kurosaki Gorozaemon regarding his relocation to the Fukagawa area reads as follows

……You are to be spared the use of both endos east of Komakasako in Sounoseyama, and you are to be spared the use of firewood. ……You are to be spared the use of lumber. ……You are to be spared the use of lumber. ……You are to be spared the use of lumber. ……You are to be spared the use of lumber. ……

The date of the letter is dated July 25, Jouou 2. From these records, it can be inferred that the Yamamura family moved to Matsumoto and opened a kiln in the early Edo period (Meireki and Jouou). In the meantime, the Miwa and Saeki kilns were established in Matsumoto, and the Sounose and Furuhata kilns in Fukagawa.

Around the first year of the Genroku era (1688-1704), there was a saying that “Hagi ware is now called Hagi ware from Hagi in Nagato Province, and is also called Hagi.

Many examples of this Hagi ware include tea bowls, water jars, and other tea utensils. It is not surprising that the style of Hagi ware is similar to Yi Dynasty ceramics of Ido, Kumagawa, and Gomoto, considering its origins, and therefore the ancient style of the pottery is quite similar to Karatsu ware. However, the reason why this type of Hagi ware is not known from the past is because old Hagi ware is mixed in with pottery from Kyushu kilns, which are also of Korean origin, as is commonly referred to as “Hagi no shichikake” (seven different types of Hagi ware). On the other hand, in addition to this Korean style, there is also Hagiyaki’s unique Japanese style pottery such as mizusashi, which looks like a copy of a bent wooden container, and sakura takadai, or a tea bowl with a petal-shaped base, which is called sakura takadai. The glaze is usually an opaque white color rich in the softness characteristic of Hagi pottery, but there are also glazes with a slightly thicker, so-called “oni-hagi,” or “devil’s bush clover. The clay also has a strong soft texture, just like the glaze. This is said to be due to the fact that the clay is taken from Daido-do Mountain in Hofu City, but it is said that Daido clay began to be used for Hagi ware in the mid-Edo period around the Kyoho period. Therefore, this type of Hagi ware was fired after that time.

Shigaraki and Asahi

Shigaraki ware was fired in the villages of Nagano and Kamiyama in Koka County, Omi Province. According to legend, Shigaraki ware was first produced around the time of the Tenpyo-Hoji period (710-794), but the earliest date is not known.

At the beginning of the Taisho period (1912-1926), a sunzutsu-shaped kiln vessel with a lid with a knob in the shape of a shamisen plectrum was excavated in Sasayama, Toki-mura, Toki-gun, Gifu Prefecture, which is commonly called Sakura-do. The clay was coarse with white pebbles and a shiny, bright brown color, and although it now appears to be Shigaraki ware, the clay skin remains intact. The design of the cherry blossoms and sparrows on the circular mirror that accompanied it is considered to be a Japanese mirror of the late Heian period, and this pottery was probably fired around the same time.

From these examples, it can be said that Shigaraki ware was produced at the end of the Heian period, but the following examples from the Kamakura period are unknown, and only a few examples from the Muromachi period are known.

This example is a jar excavated from Mt. Nagano-bou, and the “March 10, 3rd year of Choroku 3” is written in ink on the gray-colored Sue material used as the lid. The clay color of this jar is grayish-white, with few white pebbles mixed in, but it has the dried rice cake-like texture characteristic of Shigaraki pottery. The top of the rim of the jar has a toi-guchi (gutter) shape similar to the mouths of jars made in Tokoname ware, which are thought to date from the Nanbokucho period (1573-1604). Many old Shigaraki jar mouths are made in the form of a wheel shaft, similar to that of Seto ware bottles of the late Kamakura period, but the jar-like mouth of this jar excavated from Boyama suggests that Shigaraki ware was influenced by Tokoname ware as well as Seto ware.

As shown above, there are very few authentic examples of old Shigaraki pottery, but there are a large number of Shigaraki ware names that have been documented. In the early Muromachi period (1333-1573), Shigaraki ware, along with Kakuto (Bizen ware) and Seto ware, is listed as a suitable jar for storing leaf tea. In the late Muromachi period, Shigaraki pots are listed as being suitable for storing leaf tea, along with kyodo (Bizen ware) and Seto ware (Seto ware).

These Shigaraki jars were originally made to serve the needs of local farmers.

The oni no oké, which is described as “Shikaraki oni no oké Tsuji Genya’s possession,” was originally used by farm women to knit threads from cotton.

According to YASUDA’s research, the first time Shigaraki ware, which was a so-called folk art, appeared as a tea utensil was in the form of a water jar used at a morning tea ceremony held by Shimoma Hyogo, a priest at Ishiyama-ji Temple in Osaka, on Ugetsu 7, 1818. However, Shigaraki ware was rarely used for tea ceremonies at this time, and it was not until the middle of the Tensho period that it finally began to be used actively. The majority of the vessels are simply called “mizusashi,” but in the Keicho period, they were accompanied by a lid, as shown by a Shigaraki mizusashi with a “tomobuta” lid at a tea ceremony held by Oribe Furuta on November 20, Keicho 6, 1917. Also, one day later, on the 21st, Kobori Sakuusuke (Enshu) used a Shigaraki-ware water jar with a common lid at a tea ceremony in Fushimi, Kyoto (“Matsuya Kyuyo Kai Ki”). Furthermore, a Shigaraki water jar and tea bowl were also used at a tea party held by Sakuma Fukosai Nobumori in Keicho 8. From these examples, it is thought that Shigaraki ware began to be used for tea ceremonies as well as daily utensils around this time.

A Shigaraki water jar was also used at a tea ceremony held in Yamato Kaiju (Sakurai City, Nara Prefecture) in February of Shoho 3 by Oda Saemonza, the fourth son of Oda Yurakusai Nagamasu, and a sketch of the event is shown (“Matsuya Hisashige Kaikki”). The shape of the Shigaraki suizashi is similar to the “oshaburi” that infants eat, and there is a note on the side that reads “Kyokuhuruki,” which suggests that Shigaraki suizashi from around the latter half of the Keicho period had a strong taste for tea and a strong appearance.

The Shigaraki tea bowls of the Keicho and Genna periods were also strongly tea-conscious, as the pedestal of the Shigaraki tea bowl inscribed “Mizunoko,” which is said to have been a favorite of Kobori Enshu, is polygonal in shape, similar to that of Raku tea bowls, and the glaze tone from the back of the pedestal to the waist suggests that it was a so-called fuseyaki (fuse ware). Shigaraki tea bowls of the Keicho and Genna periods also strongly expressed a tea ceremony consciousness.

Thus, Shigaraki ware was widely used by tea masters from the Momoyama period to the early Edo period. As a result, Shigaraki ware was widely used by tea masters from the Momoyama period to the early Edo period (1603-1868). On the other hand, the simple beauty of Shigaraki pottery prized by tea masters was gradually lost with the firing of tea ceremony utensils, leading to the decline of Shigaraki ware.

Asahi ware is listed as one of the Seven Kilns of Enshu, along with other kilns such as Zesho (Omi), Kosobe (Settsu), Akahada (Yamato), Shidoro (Omi), Ueno (Buzen), and Takatori (Chikuzen). However, the history of these kilns is not well known. According to legend, Jiroemon Okumura, a native of Uji, started the kiln around the end of the Keicho period (1596-1598), but it was discontinued around the Shoho and Keian periods in the early Edo period (1603-1868). According to one theory, Okumura Tohei, a native of Omi, opened the kiln around the Shoho period, and his son, Fujisaku, took over the business, which was discontinued around the Kanbun period. Kobori Enshu died in February of Shoho 4, so if the kiln was opened during the Shoho period, as is later claimed, it is more closely related to Enshu’s son, Gonjuro Masayun, who is said to have given the “Asahi” seal.

The kiln site is located at the foot of Mt. Asahi, and it is said that tea utensils were made using soil from this mountain, especially tea bowls. The clay of these ancient examples is rough in texture, with numerous blackish brown flecks in the pale dark blue glaze on the surface of the bowls. The shape of the bowl is an imitation of a Korean tea bowl, which could be said to have been made in a Japanese style. The strong wheel marks from the waist to the edge of the base, the white glaze on the dark blue glaze surface, and the convex whorl pattern on the back of the base are all traces of the style of the so-called Koryo tea bowls known as well or nail carving Iraho. It can be said that Asahi Pottery is a descendant of the style of so-called Koryo tea bowls called Ido or Iraho with nail engraving.

Asahi ware was re-established by Chobei Matsubayashi, a local potter, around the Keio period at the end of the Edo period. The Matsubayashi kiln was located in Yamada, Uji-go, and fired from the soil of the Warada area, but this kiln’s pottery was not as elegant as the previous Asahi ware, and was very ordinary in style.

It is said that Ashikaga Yoshimitsu established seven gardens in Uji and gave part of them to his chief vassals, the Kyogoku, Yamana, and Shiba clans, etc. Uji was known from early on as a tea-producing region. In the early Edo period (1603-1868), in addition to private use, the Hoshino family ordered tea from the Hoshino family, which was famous for its Uji tea, and from the Kamibayashi family, at the request of the court and other families, as shown in the “Uji no Hoshino Sosho Jikichi Gonen Shojo Sento Gotsuboi Kikencha no Koto Shinkenya (……)” (Japanese only). It is likely that these events stimulated the rise of old Asahi ware.

Ninsei

Kyo-yaki of the Edo period, known for its elegant style, began with Insei, and his works represent its best. Therefore, the pottery style of Ninsei has long been passed down from generation to generation as a benchmark for later Kyo-yaki pottery.

Because Ninsei was from Nonomura, Kuwata County, Tamba Province, he took the family name Nonomura, and his first name was Seiwemon. He was called Nonomura, and his first name was Seiemon. The pottery shards collected from the remains of Ninsei’s kiln in Omuro say “Meireki 2 (1656) Nonomura Harima ……,” so it is likely that he took the Nonomura family name at that time, and until then he was called Tsuboya Seiemon or Tanba ware Seiemon. Also, it is said that when he was a young man, he dedicated incense burners to three temples, including Ninna-ji Temple, Yokoo-ji Temple, and Anyo-ji Temple in Oharano, Ukyo-ku, Kyoto, to pray for the improvement of his skills. Furthermore, the reason why he was called “Irimichi” after his devotion to Buddhism at that time is because Sowa Kanamori, who is said to have been a good mentor of Ninsei, passed away in December of the second year of Meireki, the previous year.

In August 1678, Morita Kyuemon, a potter from Oto, Tosa Province, visited Omuro-yaki on his way to Edo (now Tokyo). The report of his visit reads as follows: “I also saw the kama-sho (potteries). There are seven kettles, and the current potter is Nonomura Seiwemon,” without referring to the potter as Ninsei. However, in the previous year, in Enpo 5, there is a certificate of loan of Kaneko, which shows that the borrower was Seiwemon and the guarantor was Ninsei, and that the descendant of the Kayama family, who served Prince Ninnaji, had left the family business to his eldest son, Seiwemon Masanobu. However, in 1695, when the Maeda family of Kaga ordered Omuroyaki incense containers through the Urasenke family, a telegram was received from the Maeda family: “…Thirteen Omuroyaki incense containers have been made, but they are not very well made, so it is not convenient. Maeda Sadachika, a retainer of the Kaga Clan, wrote in his memoirs that he received a letter from the Urasenke family stating, “…the thirteen pieces of incense for burning in your room have been made, but they are not very well made…”. The fact that the Maeda family had an extremely close relationship with Munehwa Kanamori, who was the leader of Ninsei, can be inferred from the fact that Munehwa’s eldest son, Shichinosuke, was given a large stipend of 1,500 koku by the Maeda clan in 16 Kan’ei 2, the year of his death. This relationship may have been one of the reasons why the Maeda clan commissioned him to make incense for Nisei’s Omuroyaki, which Munehwa had taught. However, it can be said that Ninsei had already died by the 8th year of Genroku (1688), when he mentions that Omuroyaki at that time was Seiemon II. However, we do not know Ninsei’s age.

Insei built a kiln in front of Ninna-ji Temple, a famous temple in Rakusai, and made pottery. After the Onin War, Ninna-ji Temple had fallen into disrepair, but the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, rebuilt the temple with Kinoshita Awaji-no-Mori and Aoki Kai-no-Mori as officials in charge of the work, which was completed in the 3rd year of Shoho. In October of the same year, Prince Kakushin, the 21st successor of Ninna-ji Temple, moved from his temporary residence to the new palace, despite the fact that he was the first prince of Emperor Goyozei. Kensho Shonin of Sonjuin, who made great efforts in the reconstruction of Ninna-ji Temple, described in detail the October transfer of the temple as follows.

Record of Ninna-ji Temple’s Goyojinshi

On the 11th day of October, Shoho 3, the weather was clear and early this morning, the new Imperial Palace of Honjo was transferred to the new location. The priests and other priests of the monastery are to be sent to the south gate of the temple to receive orders from the priests of the temple. The two magistrates were to be addressed one piece of platinum for the cost of a horse.

According to this, the four “front runners” are described as non-professionals, so it is thought that they were temporary and served as favorites. However, the fact that the ceremony was held in this manner may have been due to the tight financial situation of Ninna-ji Temple. However, the reconstruction of Ninna-ji Temple has been completed, and it is expected to be an opportunity for the surrounding area to regain the prosperity it once had.

In the diary of the sixth son of Haruho Kashuji, Horin, who was born in the second year of Bunroku era and died in the eighth year of Kanbun era, there is an entry, “Kamo no Sekime Tamibu ku ku ku ku rai muroyaki no chayu ni Ichiga e no ya ……” in January of the fifth year of Shoho era. At the time, Ninsei pottery was also called Ninsei-yaki and Ninna-ji pottery, but Omuro-yaki was the most widely advocated. On the seventh day of the first month of the third year of the Kanbun Era, Uemon Yuraoka (a white flour merchant?) visited the monk Hourin to offer his New Year’s greetings. ~In addition, the Saga Gyodo (Saga Travels), which is said to have been published around the time of the Enpo Era, states, “There is a potter in front of this gate in modern times, and his name is Ninsei. …… The sign “In the early modern period, there was a potter in front of this gate, and his name was Ninsei.

Thus, since the Ninna-ji Temple was rebuilt and His Holiness Kakushin moved to the temple in October of Shoho 3, and the name Omuroyaki was first seen in January of Shoho 5, it is estimated that Ninsei must have opened his kiln in Omuro during Shoho 4 (1647).

The motive for Ninsei’s opening of the kiln in front of the Ninna-ji Temple gate may have been the so-called newly emerging area from the reconstruction of Ninna-ji Temple, as mentioned above, and the monk Horin may have also helped him. Horin was highly trusted by Gosuio-in, and often visited the Sento Palace to play renga and sugoroku (a Japanese stringed instrument) with her.

In December of the 4th year of the Kanbun Era, he was asked to accompany the Emperor Gosui’o to Shugakuin Rikyu, where he was to open a kiln for firing pottery, which was supposedly made for the purpose of making a ceremonial hand-sabiri. It is assumed that he was close to Prince Kakushin of Ninnaji Temple, who was the elder brother of Prince Gosui’o-in. In Kanbun 2, Fushimiya Choemon, a lumber merchant in Edo (Tokyo), visited Horin and asked him to assist him in selling lumber for the repair of Ninna-ji Temple. ~This is an example of the relationship between Ninna-ji and Horin. The fact that Hourin wrote in his diary in August of Keian 2, “Yakimono Shi Seiwemon Pottery Formed by Seiwemon ……, and also made by you, and also water jars, plates, bowls, etc. made by you ……” indicates that Ninsei was close to Hourin. Therefore, it is also assumed that Hourin may have helped Ninsei to open the kiln in Omuro as a result.

Looking at the world of ceramics in Kyoto at that time, there were kilns in Awataguchi, Yasaka, and Nijo Oshikoji, and records show that pottery was fired at these kilns. In April 17 Kan’ei 17, Horin visited Seibei, a potter living in Yasaka, accompanied by the Chinese goods dealer Ohira Gohei, and saw him make tea containers, incense containers, and incense burners on the potter’s wheel, and then walked to the mountain area to visit the kilns. Three years later, in the first year of the Shoho Era, Funakoshi Sotoki, a retainer of Hojo Kutayu Ujishige, a local government official in Kawachi, returned to Japan, and Hourin presented him with an incense container, which he described as a wisteria-shaped container with purple and blue glaze, which had been made by the pottery master Seibei the previous year. The glaze tone suggests that the incense container presented by Hourin was Yasaka ware, a soft pottery similar to kojitaki ware. Therefore, it can be said that the pottery produced at Awataguchi was also the same type of soft pottery. There were also kilns on Kiyomizu-zaka, Otowayamashita, and Mizoro-ike, but the details of these kilns are not known.

On the other hand, pottery from various regions was imported to Kyoto at that time. Some of the pottery from nearby areas, such as Zesho in Omi and Owari Seto, and pottery from remote areas, such as Imari, Higo, and Toyomae ware, were imported to Kyoto at that time. Unlike the soft pottery made in Awataguchi and Yasaka mentioned above, these were hard, highly utilitarian pieces, so the interest of the sukiya in them must have been high. Hourin’s frequent gifts of Imariyaki to the Sento Palace and his acquaintances is an indication of his fondness for this type of pottery. The fact that Nisei did not produce soft ceramics at a time when the interest of Kyoto’s sokusha was shifting in this direction may have been one of the reasons why he did not produce soft ceramics. It is also possible that it was more appropriate for him to build his kiln in Omuro, away from the center of the city, rather than in Awataguchi or Yasaka, as described in the “Kyuemon Diary,” where he had seven kilns.

On March 25, Keian 2, a tea ceremony held by Kanamori Sowa in Kyoto is mentioned in the Pokki of Matsuya Hisashige, a lacquer craftsman from Nara. The “arayaki” (a new type of pottery) water jar seen there is described as being a cut form of Munehwa’s Ninna-ji ware with a square body.

Munewa was the eldest son of Kanamori Kashige, lord of the castle in Hida Takayama, but he was disinherited because he disagreed with his father, who insisted that he should not participate in the Osaka campaign during the Keicho and Genwa periods. After that, he went to Kyoto to study Zen under Denso Soin at Daitokuji Temple, where he is said to have taken the name Sowa. Yamada Kouan Roshi claims that Sowa, under the orders of the Tokugawa clan, was inquiring about the movements of the Imperial Court at that time. Regardless of this, his tea style is said to have a strong flamboyance, as in the so-called “Princess Sowa” style. However, when we look at a jar by Ninsei, similar in shape to a mizusashi (water jar), as described in the above-mentioned account by Hisashige Matsuya, we can see that both the shape and glaze color are deeply subdued and subdued. Therefore, it cannot be said that Sohwa’s tea style was always flamboyant.

The fact that Ninsei went to Kyoto for training as a young man and then went to the Seto area to further hone his skills is also indicated in a book of pottery techniques handed down to Ogata Kenzan from his second son, Seijiro Toryo. The legend that he learned tea container making from Takeya Genjuro in Seto must have been born from his training in the Seto area. According to this pottery law book, there are several colors such as Kakiyaku, Kinkeiyaku, and Shunkeiyaku that are thought to have been used for tea containers, and names such as “Benisara Te,” “Seto Aoyaku,” and “Seto Kannyu Te. Seto Seiyaku” is a copper glaze often used in Oribe ceramics, and “Kanyu Te” is thought to refer to the glaze tone of Shino ceramics. Also, “beni saucer hand” is not clear, but it was used in Oribe ceramics at that time. It is not clear, but it may be Kiseto, which flourished together with Oribe and Shino at that time.

Some of the examples recognized as Nikiyo-yaki ware are oddly shaped, such as Zoshi or Houragana, which are designed to burn incense, but look like tokonoma (alcove) decorations or indoor long-hanging nail-holders. However, tea utensils are the most common type, including jars, water jars, tea bowls, tea containers, and incense containers. The jars that are representative of Inseong ceramics are those that are thought to have been displayed at tea ceremonies at the opening of a tea ceremony, and are in the form of the so-called Lu-Song jar, which was imported in the late Muromachi period and was called “true jar,” “Qingxiang jar,” or “Lotus King jar. Since Lu-Song jars were considered suitable for storing tea leaves and were highly prized from early times, it is likely that the shape of the Renqing jar was modeled after them, but some of them have a different style, such as the aforementioned jar with a square body. The outer surface is covered with a white glaze with polygonal cracks, known as rensen kanmu, while the bottom is glazed with a clay skin, known as a hemmed glaze.

Compared to jars, mizusashi are more varied in shape, including yugata, bawara, and sunaganebako forms. They also have a variety of ears on the body side, such as the take-shaved, bracken, and tied forms. Some of the jars are so-called “Nikiyo-Shigaraki” type, which make the most of the clay flavor, while some of the mizusashi are Shigaraki copies, while others are Nanban copies, and the variety of styles that make the most of this clay flavor is as diverse as the shapes.

The characteristics of Nikiyoe pottery shown in these jars and mizusashi are often seen in tea bowls, which are the most common type of artifacts left behind. Some are neatly shaped, like the tea bowls that were prized at the time and called “Gohon” and “Kureki,” some are slightly constricted at the center of the body, as if the shape of a well tea bowl had become Japanese style, and some are cylindrical, similar to the shape of a tea bowl inscribed “Hikiki-Saya,” which was considered a masterpiece from early on, and many are shaped like the so-called Koryo tea bowl, which was considered to be a turtle-shaped bowl. Many of them are shaped as if they were made from Kamekami, the so-called Koryo tea bowls, which were famous from early times. The common feature of these bowls is that the curved surface from the waist to the base is soft, while the base is sharply defined as if a round seat were attached to it. Another common feature is that the high pedestal shows the elaborate technique of the potter’s wheel, as shown in large works such as jars and water jars. The glaze is white translucent or opaque, similar to that of jars and water jars, but the cracks are very small, unlike those on jars. Some are dyed in the broad sense of the term, with figures and flowers painted under the glaze in rusty iron colors, while others are decorated with red, green, gold, and silver on the glazed surface, with the latter being particularly common. There are also some unique types that are partially sprinkled with white glaze to express a wave-like wave pattern, making the most of the texture of the base clay.

The patterns of the tea bowls, which are decorated with gold and silver, are similar to those of dyeing and weaving, and the wave patterns on the scales and the gold and silver stripes are good examples that immediately remind us of Noh costumes. The technique of raising the gold and silver high is similar to that of maki-e, which is also not to be overlooked.

The Yongshu Fushi (Yongju Fushi) describes this type of painting as follows: “In modern times, a place in front of the Ninna-ji Temple gate was producing Ninsei ware, which was called Omuro-yaki, and Kano Tanyu ordered Eishin and others to paint on it.

Kano Tanyu was a close friend of the monk Horin, often visiting Ninna-ji Temple and Horin when he went to Kyoto, and also communicating with Horin from time to time in Edo. However, since Tan’yu was in charge of the Shogunate’s painting office, it is unlikely that he directly wrote on the Insei pottery.

However, considering the relationship between Tanyu and Ninsei in Hourin, it is conceivable that Tanyu’s disciples in Kyoto may have dyed the brush strokes.

Next, all of these tea bowls are stamped with the inscription “Ninsei,” but unlike those on jars and mizusashi, they are small in size, which is natural for small bowls, but they also use what is called an “ouchi seal,” which has a hanging curtain at the top of the spine, or a cocoon-shaped outline, which is not found on jars and other tea bowls. The style of calligraphy is in the same cursive style as that of the jar and the water jar, and the stamping on the back of the base is in the same acute position as that of the painting, like a conscientiousness. Insei’s awareness as a potter may have marked all of his vessels, and this style was a distant cause of the emergence of individual artists in Kyo-yaki later on. This was another significant mark left by Ninsei on Kyo-yaki pottery.

Inzan

The style of pottery created by Inzan, who was born in the Genroku period of the mid-Edo period, had as great an impact on the development of Kyo-yaki as that of Ninsei.

In his own handwritten biography, “Toko no Hitsuyo” (Essentials of a Potter), he wrote, “…… is located in the northwest of Kyōjō, so the name of the pottery is written Qianzan-tō. ……”, stating that the name Qianshan was used only for ceramics. This is also indicated by the inscription on the back of one of the most representative examples of Qianshan pottery, a square dish with a painting of a seagull in the Huangshan Valley, which reads “Dainihon Yongju Qianshan Pottery Hiding Deep Province …….

The pottery method is as described in the biography: “The workman Sunbei, who is a relative of Oshikoji pottery and a disciple of the master, is a master craftsman of Oshikoji pottery, The hard, hon-yaki pottery was inherited from Ninsei, while the softer, kojigi-te style was inherited from Oshikoji ware, to which he added his own innovations.

It was in the 12th year of the Genroku era (1688-1704), when he was 38 years old, that Kenzan opened a kiln in Narutaki, located in the western part of Rakusai. At the age of 25, he was bequeathed Ingetsuke’s ink rubbings and a set of books, along with houses and residences in Muromachi Tachibana-cho, Joka-in-cho, and Takagamine, by the will of his father Soken. The fact that Inzukue’s calligraphy and books were given to Inzan shows that Inzukue was the third son of Gankinya, the kimono purveyor to Tofukumonin, and that he had the education and character of a wealthy merchant. Three years later, in the second year of the Genroku era (1688-1704), he retired to Nashiseido in Omuro, and since the Niseido kiln was located near Nashiseido, he visited Niseido’s kiln from time to time to make pottery, which probably contributed to his later establishment of the Narutaki kiln. It is also said that the Narutaki area was owned by the Nijo Tsunahira family, but was given to Kensan. The fact is that the property was transferred in the seventh year of the Genroku era (1688-1704), when the second generation of the Ninsei kiln was finally declining, and this is also thought to have been a factor in the opening of the Narutaki kiln. In the products of the Qianzang kiln, which opened in October of the twelfth year of the Genroku era (1688-1704), we can often find examples of paintings done by his brother Korin, to which Qianzang added inscriptions or inscriptions of his own. These designs show the throaty, rounded lines characteristic of the Rimpa school, but on the other hand, there are paintings with a more rigid brushwork similar to the Kano school, which are labeled “Soshin”. This Soshin is said to have been Watanabe Hajimeoki, a retainer of the Konoe family who first learned the Kano school and later studied under Korin. As Kenzan said, “I let Soshin paint when I was tired.” At times, he even had Soshin paint and write calligraphy on his behalf. Therefore, it can be said that there are some pieces with “Qianzan” inscriptions that are recognized as having been made by the Qianzang kiln that were not directly handled by Qianzan.

The products of the Qianzang kiln fired in this way were publicized by people who knew Qianzang and became known to the world. However, making pottery was usually unprofitable in the old days, as seen in the case of Insei, who borrowed money in his later years. Therefore, the amount of money that Qianzan injected into Narutaki-gama during the few years that he ran it must have been enormous. In addition, he had to help his flamboyant elder brother Korin, who was in dire straits, and it can be assumed that Korin’s money was often in short supply. Furthermore, Nakamura Kuranosuke, a senior official in the Ginza district of Kyoto, who is thought to have been a good supporter of Korin’s pottery, lost his position in Shotoku 4. He was fifty years old at the time. During this period in Chojiyacho, his adopted son, Ihachi, who was the son of Ninsei, assisted him, and it is said that he fired in a common kiln in Awata. However, in November of the 2nd year of Hoei (1704), there is an entry in the “Omuro Goki” (“Omuro Goki”) that reads, “…… came from Hatsukaichi until Hatsukaisan fired in the kiln ……,” indicating that Inzan occasionally fired in Narutaki as well. However, the Dingjiya-cho period was a time of disappointment for Inzan, so to speak, and his artistic ambition was not as vigorous as it had been during the Narutaki period, and his work was apparently sluggish.

In November of the same year, he accompanied His Imperial Highness Prince Rinnoji on his return to Tokyo and lived in Iriya, where he was engaged in pottery production. It is said that the firing site was near Onoteru Shrine in Sakamoto, Taito-ku, but this is not known for certain.

In addition to the overglaze overglaze enameling on the main body of pottery passed down from Ninsei, there are also underglaze black, cast, or gozu underglaze paintings, as well as soft ceramics of the Raku ware quality handed down from Magobei. Among these, the most unusual types of Qianzan ceramics are those with white glaze applied to all or half of the surface of the vessel and painted patterns on the surface of the glaze using green, indigo, or gold, or painted with blue glaze behind the glaze.

As stated in his writings, “The white glaze is the best-kept secret in the house, and it is difficult to explain in writing, but it can be handed down orally.

As a result, the best white clay for hosho-shi, which comes from Akaiwa Village, Kusu County, Bungo, is described in the biography as “the best. At the time, white porcelain from Hizen was highly prized, and this may have influenced Qianzan’s firing of white glazed ceramics, but on the other hand, the fact that colored clay was not effective in expressing the style of calligraphy and painting in ceramics, which was his specialty, led to his dedicated search for white clay, even though he said, “The red and white earthenware of the world is not perfect, This must have been the reason for the earnest pursuit of white clay. The Nezu Museum’s collection of earthenware plates with different patterns is a typical example of this type of pottery.

In addition, Kenzan wrote in his biography about Raku ware, “The secret of Kyo Raku and Akaraku has been handed down from generation to generation, but it has not been handed down in the Noru family since Rikyu, so I have not written it down.

The reason for this “Kateyute ……” is that a son of Gankinya San’emon of the main family was adopted by Raku Ichiiru, and because the Raku family at that time was in a state of “poor people living in two houses until Ichiiru” (“Rindosai Secretaries”), the so-called side kilns, which would interfere with the Raku family’s occupation, were not used for firing. This may have been due to Kenzan’s concern about the firing of so-called “side kiln” pieces that would interfere with the Raku family’s profession. Therefore, there is no red color in Raku ware tea bowls made by Kenzan, and black glazed ones are seen only rarely. This black Raku also has a style of showing a large pattern of petals on the surface of the bowl, and there are no examples of Raku tea bowls with no pattern, which is typical of Raku tea bowls, and also no examples of tea bowls that show traces of painstaking effort in their modeling.

What is noteworthy about Qianzan ceramics is that the design of the patterns is similar to that of dyed textiles.

This tendency may be due to the fact that Qianzan grew up in a kimono merchant family, and the use of stencil dyeing techniques to express these patterns suggests that the Qianzan kilns produced large quantities of similar wares. Therefore, if this type of work is recognized as being made by Qianzan, the number of examples of Qianzan’s work would be extremely large. However, as mentioned earlier, Kensan was an individual artist who expressed his own motivation for writing and painting on clay, and we must consider the possibility of recognizing even these katagami-based designs as his own work.