Mishima, Hakeme, Kumagawa, persimmon calyx, calyx, toddy, Wu ware, split height stand, Goshomaru, Irabo, carved Mishima, Unkaku, Gimhae, Gohon, Koryo

The collection includes Mishima, Hakeme, Kumagawa, persimmon calyx, toya, Kureki, Ware, Waritakadai, Goshomaru, Irabo, carved Mishima, Unhak, Gimhae, and Gohon, which can be roughly divided into two categories in terms of their taste. The two categories are those that were originally made in Korea as purely utilitarian vessels, but were later adopted by Japanese tea masters as matcha bowls, and those that were made by tea masters from the beginning, and were made as matcha bowls according to their preferences. Mishima, Hakeme, and Kumagawa are good examples of the former, while Goshomaru, Iraho, and carved Mishima are good examples of the latter.

At first, Korai tea bowls were collectively referred to as “Korai tea bowls,” but eventually specific ones were given names such as “Ido” and “Mishima,” and thus the classification gradually progressed, with most of the names already in place by the Genroku era (1688-1704).

The development of these classifications was prompted by the convenience of use in the tea ceremony, and it is obvious that the scrutiny of the tea bowls went from simple and coarse to more detailed in the evaluation of the tea ceremony as well. The charm of Koryo tea bowls was first discovered by the excellent sensitivity of tea masters cultivated in the Japanese climate, and in the process of this examination from simple to detailed, their senses were further refined into delicateness.

For each of them. The highlights or promises extracted in detail to the point of being troublesome may at first glance seem to be an empty formality, but upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that the senses of the tea masters, which have been refined over many years on the basis of Japanese sensibilities, are really crystallized in these enshrines. The sum total of these senses, or perhaps we should call it a system, is the treasure that has been accumulated and built up in the world of chanoyu. The tea ceremony is a treasure that has been accumulated and built up in the world of chanoyu. This is what tea tastes like.

The charm of Korai tea bowls can be summed up in one word, “sakurabi,” but the real pleasure of sakurabi among sakurabi, such as kakinokake, totoya, and iraho, can only be experienced with a well-developed taste. For example, even a seemingly dull, monotonous, and tasteless skin is filled with infinite changes that are more than five colors. For tea masters who have refined their senses to the highest level, the end point of the Korai tea bowl award is said to be the aforementioned sabimono, and the secret of its charm can only be revealed through their eyes that have undergone rigorous scrutiny.

Mishima

The name Mishima, along with Ido, was known among tea masters from early on among Koryo tea bowls, and the name Mishima tea bowl can already be seen in the “Tsuda Munenori Chayu Nikki” on the morning of November 17, Eiroku 11, in the Toikai. The origin of the name Mishima is probably older than the well, and it is thought to have existed not only in the late Muromachi period, but even before that.

The distinctive feature of Mishima is the white inlaid pattern, which can be seen both inside and outside of the bowl. However, in most cases, the process is so careless that the white brush marks remain, or the white makeup is left almost as it is and becomes a powder-coated finish, which adds a more refined and wretched appearance.

The name “Mishima” is derived from “Mishimano-ryomi” (Mishima calendar), which was compiled in the 7th year of the Genroku era (1688-1704) in “Wakan-roku Shohutsu Mishisa,” which states, “Mishimate” means “a vertical, narrow picture on the front of a tea bowl as if it is a Mishima calendar (a calendar written in kana and small letters published at Izu Mishima Shrine since the Onin and Bunmei eras), and thus it is also called “karyote” (calendar). The name “Ryokute” has also been used since ancient times. For example, in the “Kamiya Sotan Diary,” on the noon of February 29, Keicho 4, in the Fushimi Prime Minister’s Meeting, it is written, “Chawan ha koryo ya, koyominote ya,” which has been called Mishimanote or karyote for centuries, and the term “Mishima karyote” is also found in the abovementioned “Michisa,” so this theory is the most reasonable to start with. This theory is the most plausible. However, the name “Mishima” later came to be used in reference to Koryo inlaid celadon porcelain, which was sometimes inscribed with the name “Mishima” in a box.

Another theory is that it was called Mishima because Geomundo used to be called Mishima and was a strategic point for trade in the South Sea, and pottery exported through this port was called Mishima. Another recent theory is that Mishima is an ancient name for Korea in Japan and, like the Koryo tea bowls, was probably called Mishima in the sense that it was introduced to Korea.

In terms of technique, Mishimategate is a degenerate version of the Goryeo inlaid celadon, but some inlaid celadon of the late Goryeo period already has a Mishima-like pattern. Mishima-te began at the end of the Goryeo Dynasty and was fired in the entire Namcheon region from the 15th to the 6th century, from the early to the middle of the Yi Dynasty. Mishimadate came to Japan in the Muromachi period (1336-1573), and most of the tea bowls are from Goryongsan (Chungcheongnam-do) and Gyeongsang and Jeolla Provinces.

Tea masters further divided Mishima-te into various categories, calling them Ko-Mishima, Reibin-Mishima, Sansaku-Mishima, Hana-Mishima, Uzumishima, Kuro-Mishima, Kaku-Mishima, etc. Recently, the name “Joryongsan Mishima” has also been used in reference to the place of production.

Ko-Mishima

Ko-Mishima” is usually understood as simply “old Mishima,” but tea masters refer to it as “rin-kirin” with a warped edge, a thick glaze, light black clay, and a heavy hand. This type is the most common type of Mishima tea bowls in the history, and is thought to be from the Gyeongsangnamdo region, probably because of the long history of negotiations with our country. In addition to Ko-Mishima, Mishimate are usually fully glazed. Hana mishima” refers to those with small chrysanthemum inlays, “whorl mishima” refers to those with three or five whorl inlays on the prospective surface, “kaku mishima” refers to those with angular inlays connected in a band, and “sanzaku mishima” refers to those with mishima on the interior and kohiki on the exterior, with brushwork on the sides of the base.

Reibin Mishima

A teacup with a white inlaid inscription “Reibin” on the front surface, which is often used for flat teacups. There is also one inscribed “Reihin Toriyo. These were originally furnished for the government office of the Yi Dynasty called “Reibinji,” where foreign guests were entertained, and were carefully made, so many of them are very skillful. The glaze is also quite good, so much so that it is commonly referred to as “Yeobin glaze. Even though there is no inscription, a fine mishima similar to this hand is also sometimes called a reihin-te.

Other Yi Dynasty government offices with inlaid inscriptions on their mishimas include Jangheunggang, Naesuji, Naemyori, Sajeon, and Inju-bu. Jangheunggang, which was in charge of tax collection, also bears the names of the regions of Gyeongju, Gyeongsan, Miryang, Changwon, Jinju, Eonyang, Jinhae, Yangsan, Ulsan, Goryeong, and others. These are also known as “Raehinde”. In addition to inlaid inscriptions, there are also engraved inscriptions and inscriptions written in black. The curious calligraphy of the inlaid inscriptions is more intriguing and fascinating to tea masters than the random Mishima patterns.

The reason why the name of the government office was engraved on this mishima is that the Yi Dynasty had pottery from various regions delivered to the government as a tax, but due to a long-standing vice since the Goryeo Dynasty, the government officials often paid the tax in cash. In the case of changheunggukou, the name of the office was written on the plate. In the case of the Changheung storehouse, it is likely that the name of the place of production was also added because the storehouse was in charge of storing and storing taxes and had the most negotiations with various places and in larger quantities. Since the dates of existence of each of the above yakusho are known, they are useful in clarifying the age of Mishima-te, and those with place names can be used to confirm the place of origin.

In recent years, many Mishima with the yakusho inscription have been excavated, and we have come to see various types of Mishima other than those with the Reibin inscription, but the Reibin inscription is the most common among the oldest pieces handed down from generation to generation. This is probably because the first place Japanese envoys to Japan were received at was the Reihin-ji Temple, which was a government office with which the Japanese had the closest negotiations, and so there were naturally many occasions when they were presented with or requested Reihin Mishima, the furnishings of the temple, as a memorial gift. Because of its distinctive inlaid pattern, the Mishima probably attracted the interest of the Japanese people as early as the Muromachi period (1336-1573), but it is likely that the Mishima, especially the Reihinte, was already highly prized among the cognoscenti in the early Muromachi period (1333-1573).

Three Islands of Mt.

Chungcheongnam-do’s Choryongsan is the most representative site of Mishima-te kilns, but its heyday was in the early Yi Dynasty, and in addition to Mishima-te, various other techniques were produced, including brush-glazed, painted brush-glazed, carved Mishima, tenmoku glaze, and white porcelain. From the end of the Taisho era (1912-1926) to the beginning of the Showa era (1926-1989), large-scale excavations were conducted, and a detailed research report based on these excavations was published by the former Korean Governor-General’s Museum in 1927. The Mishima of this site is thin and sharply made, with a small and tight height, giving it a light and lively appearance, very different from other thicker and heavier types. This is the reason why it is known as “Chicken Dragon Mountain Mishima.

The base has a high iron content. This Mishima is an old type of pottery that has been handed down to Japan for centuries. The famous Ueda Rekite of the Nezu Museum, for example, is believed to have come from this kiln.

Brushstrokes

Hakeme” means “brush marks” in Japanese, and the name derives from the fact that there are brush marks on the inside and outside of the pot. This brush pattern has a kind of pattern-like effect, and is a major part of Hakeme teacups as well as Sakuhachi-ki. Like Mishima, it was fired in the early to mid Yi Dynasty in the Namsun area, and has many points in common in terms of style, so it is appropriate to call it Mishima Hakeme as a whole, as it is like a blood brother. It is appropriate to call them “Mishima Hakeme” as they are brothers in blood.

The technique of applying white mud to the base had already been used since the late Goryeo period (kakihoshi-te), and the hageme technique is also a continuation of this practice.

Hakeme is a simpler decorative method that was born in the Yi Dynasty, when white glaze became less time-consuming due to the need for mass production.

The brushwork is often all-glazed, with bamboo joints on the base and a kabukin inside the base, but most of the pieces that have been handed down through the ages to Japan are from Gyeongsangnamdo, Jeollanamdo (Hampyeong) and Chungcheongnamdo (Mt. Joryong). Tea masters further divide brush marks into ko-hakeme, tsukahori-hakeme, inahakeme, jiryongsan-hakeme, and plain-hakeme, etc. The ko-hakeme referred to by tea masters are rim-shaped, slightly warped, thickly glazed, with a light black clay, heavy to handle, very fine brush strokes, and strong work with a well-like plateau. The brushwork is fine and the base is strong, similar to that of a well. The term “Inahakeme” is derived from the character for “inahakeme,” meaning that the brushwork is insufficient and indistinct. The outside of the bowl, however, is promised to be free of white brushwork below the waist, and was fired in Jeollanam-do (Hampyeong). The “Meimono Chawan Oomishima” is included in the Mishima category in the “Taisho Meikikan” because of its name, but it is a kind of plain brushwork hand, and is also included in the brushwork category in the “Meimono Chawan Shu”, featuring dark brushwork and inscribed “White Beard”.

Kumagawa

Kumagawa is called “komogai” or “komogoe,” and among Korai tea bowls, it is one that shows dignity on par with Ido in its ancient and elegant appearance and style, and has been admired by tea masters for its dignity since ancient times. It has been popular in Japan since ancient times, and there are a relatively large number of pieces handed down from generation to generation, but the age of production is also slightly on the edge of warp. The clay is usually white, sometimes red, and this hand is called Shikumagawa. Both types of clay are fine and viscous. The glaze is usually loquat-colored, similar to that of Ido glaze, but softer in tone and with fine penetrations. However, in the case of the later examples, the glaze has often changed to a blue-lieutenant color. In the section on Kumagawa in the above-mentioned “Michisa,” there is a reference to this when it says, “Yaku ha nezumi, pale yellow. Kumagawa of the present day often has blotches like leaks in the rain, which are admired by tea masters for their scenic beauty. The body is rather thick, and the base is made of bamboo knots, and the base is unglazed with earthenware. The inside of the base is rounded off, which is a distinctive feature. The tea bowl is circular and slightly depressed, which tea masters call “kagami” or “kagami-fall” or “ring”, which is a promise of Kumagawa. The smaller the mirror, the better.

The name “Kumagawa-shi” is derived from the name of the port of Kumagawa, which is located near Busan. Kumagawa was the most active port for trade between Japan and Korea during the Muromachi period (1336-1573), and many Japanese resided there, and for many years there was a Japanese-style house there. As a proof of this, a document from the time of Hideyoshi’s invasion of Korea mentions Kumagawa as “Komokae”. It is thought that, just as Arita-yaki produced by the Imari Port Karo-bune was called Imari-yaki, tea bowls from nearby kilns produced from the port of “Komokae” were called by Japanese tea masters with the name “Komokae”. In the “Mishisa,” Kumagawa is also referred to by the byword “Komokakae” without all the muddy words, and it is likely that it was only later that the name was muddled and called “tomogae. Near Kumagawa, those from kilns near Jinju, Gyeongsangnam-do (South Gyeongsang Province), most closely resemble Kumagawa handles, so Sonogawa tea bowls were probably produced at these kilns.

Kumagawa tea bowls probably came to Japan during Hideyoshi’s Korean War, but judging from the history of Kumagawa Port, it is thought that they may have come to Japan as early as the Muromachi period (1336-1573), and their appearance as tea bowls is thought to be as old as Mishima. Kumagawa seems to have been especially popular among tea masters because of its elegant appearance with a trace of tenmoku style, or because the edge of the mouth was good for drinking tea, and its influence is surprisingly wide, and many Kumagawa-shaped bowls are imitated in Ko-Karatsu and Ko-Hagi. Kumagawa has few special features, but it has a calm dignity that is unmatched by other styles. The reason for the special mention of a scene of a leaky roof in Kumagawa is probably due to the quietness of the work.

The main types of Kumagawa include Makuma-gawa, Hamgyeongdo, Shikuma-gawa, Onikuma-gawa, Hira-gawa, Go-guma-gawa, and Nameguma-gawa.

Makuma River

This means “the main branch of Kumagawa. The shape is deep and elegant with a neat appearance. The base is a fine white clay with a loquat-colored glaze resembling a soft well with fine penetrations. The base is made of bamboo and has crepe wrinkles inside. The base of the bowl is earthenware, but in many cases, the base of the tea bowls of this period has become stained brown and the glaze has a blue or persimmon color. The glazed surface is often blue or persimmon colored. The Konoike family’s Hanazuri teacups are famous for this leaking rain, and the name of the bowl was also named after this leaking rain scene. The prospective mirror is small and precious. The mirror is thick and heavy, but the upper part of the bowl is thin and has a small base. The tea ceremony masters call it “kamgyeong-do” (also written as “kamgan-do”) because of the skillful use of this type of mirror (“Kichisa”, “Kamgyeong-do Kumagawa no de-nari”). The Chitose nazo, which was handed down from Fumai, is a typical example of this type of work.

The base and glaze of Kumagawa are very similar to those of kilns near Jinju, and are believed to have come from that kiln. During the Goryeo period, this kiln produced distinctive white porcelain with a soft, fine-grained, through-cut glaze with a light bluish tinge on a fine white base, and Yi Dynasty Makgumecheon wares are considered to be in this tradition.

It is small, thick, and has a varied workmanship, with a shallow bamboo base and a large mirror with a sandy finish. The glaze is often loquat colored with occasional fire changes and blotches. The glaze is often loquat colored, sometimes with fire and blotches. Some pieces are white clay with a translucent white glaze. Onikumagawa has a flavor not found in Makumagawa, and is favored by tea masters as a kind of “blue well” in contrast to “big well.

The Hirakuma River is similar to the Onikuma River, which is made of red clay and has no mirror at its prospect. The “Mishisa” describes Gokumagawa as “Gowatari nararu, takaidai no uchi ni yaku kakeru,” which means that it is characterized by its lack of dohimi (full glaze).

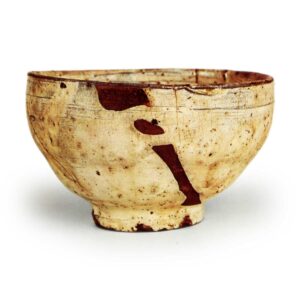

Kaki (persimmon) calyx

Kaki (persimmon) calyx is so named because its shape and color resemble the calyx of a persimmon. There are only a few of them, and together with totoya and iraho, they are considered to be the best examples of sakurabimono.

The style has many characteristics, and tea masters have given various promises. The mouth is slightly upturned, with a step at the waist and a wide opening. This shape is unique to the persimmon stem, and the face down position is similar to a persimmon stem. It is thick, but the texture is light to the touch. The edge of the mouth is cut with a spatula to form a gutter. This is one of the promises of the potter, and the sharpness of the spatula cutting is highly prized. In other words, a strong, clear impression of the workmanship is appreciated. The height of the stand is a large, repellent stand, which is also a promise. The inside of the base is rounded off as if it were gouged. The base is made of iron-rich, sticky sandy clay, which has been fired to a rich brownish color. A bluish glaze is applied very thinly to the base. Tea masters call this glaze “beadlo glaze,” and they are pleased to see a lot of glaze on it. However, there are also some that are almost unglazed, with little glaze on them. The base has a fine stripe of mizuhiki (a technique used in mizuhiki), and the prospective surface has an eye. This “grain” is also found in other Korean wares, but it is one of the highlights that should not be overlooked, especially in sakurabimono.

Some totoya are similar in shape and look like persimmon calyxes, and are commonly known as persimmon calyxes, but totoya are thinner and harder, and the texture and workmanship are different. Some people consider the kaki no 蔕 to be a totoya no ichi te and the totoya no ue to be a kaki no 蔕, but there is a clear difference between the two.

Kaki-no-tame is considered to be from the Gyeongsangnam-do region in terms of its clay type, and the fact that it has a technique of cutting and turning in the same style as Honde and Iraho, as well as the fact that it has a different style of glaze and texture, suggests that it was fired in a kiln near Busan during the period of the Dumoepo Wakan in Busan (Gyeongchang 12 to Yeonbang 5). It is thought to have been fired in a kiln near Busan during the period of the Dumoepo Wakan in Busan (Keicho 12 to Enpo 5).

Toto-ya

The origin of this name is said to date back to the time when a wealthy merchant in Sakai, Uoyaya (Togaraya), brought a shipload of this type of tea bowl from Korea. The name on the box is usually written as “Touzuya,” but sometimes you can see it written as “Watarato-ya” on an old box. The tea ceremony book says that it was called zaramegi in ancient times, but the “Mishisa” says, “It is a good thing to be a kind of zaranmomen well, so it is called sarameki well. The name “Zarameki well” also seems to be a totoya.

The totoya, along with iraho and kaki no wakame, is a particularly austere and lonely type of Korai tea bowl, and is especially prized by tea masters, probably because of its deep charm in contrast to the bright color of the tea. The base is a fine, fat clay with a high iron content. The bluish glaze is applied very thinly and does not look earthy, but the reddish fire change, a characteristic of Totoya, and the red spots of deer (Iwajuru Gohon) that often appear are indicative of clay from the Busan area. The fine stripes of mizuhiki (a technique used in mizuhiki) are vivid inside and out, and are one of the highlights of this ware. The thinness and sharpness of the work is also a major characteristic of TOTOYA. Because the clay is fine fat, beautiful crepe creases are formed on the inside of the takaidai, and the shape around the width of the helmet is just like the back of a shiitake mushroom, which is why it is commonly called a shiitake mushroom takaidai. The key to the beauty of the totoya is that it is generally austere with a bluish-grey tinge, but has a reddish hue. The totoya, when examined in detail, is as if it were made in a haphazard manner, yet it is well-designed and perfect for tea, and cannot be considered as a mere utilitarian vessel. The cut and turned shape of the toiya is a clear proof of this, and from the reddish-brown clay, it seems to have been fired in a kiln near Busan during the period of Mamoepo Wakan, in response to the tastes of tea masters.

Tea masters divided the tea bowls into two types, the honte and the flat bowls, mainly based on their shapes.

Honte and to-Ya

Honde totoya is the most prized of all totoyas, and is characterized by its shape, which is more graceful than the plain totoya, with a curved mouth edge and a tight body. It has a tight body and a swollen waist. The shape of this type of spring silkworm is similar to that of a persimmon stem or soba (buckwheat noodles), and the wider bowl makes it suitable for tea making and tea drinking.

The base is a fine fat clay with iron content and is covered with a translucent slightly bluish self glaze that is very thin. Due to the nature of the clay, the base is reddish in an oxidizing flame and bluish and hardens in a reducing flame, but it sometimes changes to a reddish blue when the flame is switched. In some cases, the reddish background is replaced by a bluish background, while in other cases, the reddish background is replaced by a reddish background and a reddish-blue background is replaced by a reddish-blue background. This phenomenon is originally an accidental formation based on the clay. In the case of TOTOYA, the pottery was probably fired in anticipation of this effect. It is just like the scorching of old Iga.

The sharply cut edge of the mouth further emphasizes the sharpness of the workmanship, and the stand is made of bamboo joints, within which the width of the helmet stands out elegantly, with fine crepe creases all around it, making it a so-called shiitake stand. The eyes are elegantly lined up on the front and back, and the fine stripes of the pulls are beautiful inside and out, making this piece a highlight. Honde toiya are generally large in size, and small, tight pieces are rare and highly prized. From the details of its style, it can be regarded as a kind of Gohon tea bowl made by a tea master who fired in the vicinity of Busan.

Tohte and Ya

This is a flat tea bowl of various sizes. The fine clay is wheel thrown on a skillful potter’s wheel, and the thin, well-finished, and lively and crisp characteristics of the todo-ya style are more apparent in this type. A blue glaze with a red fire or a reddish reddish glaze on a blue body is called “ao-toya,” and is considered a fine piece of work. The clay is finer than that of the main hand, and is commonly referred to as Koshido-Toya, and the crepe creases within the takadai are even more beautiful, showing the characteristics of shiitake takadai very well. The fine lines of the pulls are also vividly expressed both inside and outside due to this clay texture, adding a sharp feeling, and there are usually about eight elegant-looking eye marks in a row on the prospective surface. The height is lower than the main hand. The hand and the thickness of this flat tea bowl can be considered as a kind of Gohon tea bowl made in the vicinity of Busan, in view of its style.

Wu ware

Goki” is also written as “go-ki,” but both are derived from “go-ki,” and the shape of the bowl resembles that of a wooden bowl, hence the name (go-ki has been a common word since ancient times, leaving traces in “go-ki-wash” for clearing water, “go-ki-zure” for sagging around the mouth, etc.), In the Muromachi period (1333-1573), it was already used to refer to tea bowls, and the character for “kureki” also appears. (The word “kureki” can also be found in an article from the Kasuei Nenkan period of the Bitaniki.)

It is covered with an opaque light bluish glaze and fired to a persimmon or bluish color. Compared to later Gohon wu ware from the Mameurawakan period, this ware is harder in the firing process. The glaze is applied all the way up to the base of the bowl, and the inside of the base is rounded off like a scoop, which is very characteristic.

Wu ware-shaped bowls were originally found in Goryeo celadon, and Yi Dynasty wu ware is a descendant of this type of ware, but some of these bowls are considered to be no older than the early Yi Dynasty because of the sharpness of their shape and workmanship.

Wu ware is not only fixed in form, but also has a variety of glaze annealing, reddish mottling of the deer, and areas where the glaze has been removed (i.e., the glaze is not glazed). In the case of Wu ware, however, the word “kakehama” is used instead of “hama” as is customary among tea masters. In the case of Kureware, it is called “kakehazashi” instead of “hima,” as is customary among tea masters, who especially admire the incidental scenes such as the “kakehazashi” (the part where the glaze is left on), the finger marks (finger marks are left when the glaze is freshly applied), etc. Tea masters, whether Koryo tea bowls or not, do not appreciate plain and monotonous tea bowls, but rather seek for a varied glazed surface that has something to offer, as well as the quality of the workmanship, and praise these as scenery. Ko-Iga, which is considered the ultimate in Wabimono, is also generally quite elegant, with burn marks and bead marks, etc. In short, for tea masters, lukewarmness is not acceptable, and a clear impression is appreciated.

There are various types of wu ware, including daitokuji wu ware, momiji wu ware, kiri-wu ware, bansho wu ware, nun wu ware, and yugei wu ware. In addition, there are also Gohon kureki, which are softer and more delicate than the former, with more firechanges and deer eggs.

Daitokuji Ware

The name “Daitokuji Kureki” comes from the fact that in the Muromachi period (1336-1573), a Korean envoy to Japan donated a piece of Kureki he had brought with him to Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto as a commemorative gift upon his return to Japan, and the same type of Kureki was called “Daitokuji Kureki”. It is the oldest of all the Kure vessels. It is large in size, has a high base, and a strong outer opening with a strong repellent base, giving it an imposing appearance. The mouth rim is usually blue in color, and there is a stripe running along the inside of the base. Although there are some omissions in the design, the overall appearance is austere and plain.

Autumn Leaves Ware

This piece is a good example of Daitokuji Kureki ware, and is exceptionally better made than most. The oxidized flame gives it an overall reddish hue, and the blue tones of the white glaze, finger marks, and the scene of the removal of hangers, combined with the bluish hue of the fire, give it a unique beauty. The name “Momijo-Kureware” comes from the distinctive reddish color. The Kashimaya (Hirooka family) Momiji ware and the Chikusaya (Hirase family) Momiji ware are famous as the twin perfect examples.

Kikiri-Kureki

Thin, mostly small in size. Most are light persimmon in color and have a tama-edge with a pickout at the upper edge, and also enjoy a hang-up or wari-takadai. The name is derived from the dent in the prospective tea bowl, as if it had been poked with a cone. It is also said that the name “kiri-kureware” was derived from the term “kiri-kureware” for cut glassware with a cut height, which in turn became “kiri-kureware”.

The name “nun kureki” is said to have been derived from the likeness of a nun priest because the mouth was made in the style of an ubaguchi (a woman’s mouth) and was held up by the body.

Wari-takadai

There is no uniformity in terms of the base and glaze tone, with some wares having a hard hand, others having a well or Kumagawa style, and still others having a new or old style. Some of the wares are purely Yi Dynasty ritual wares, while others were made in response to the tastes of tea masters, suggesting that it would be impossible to say for certain which period, at which particular kiln, and in which kiln they were all made in the style of tea masters. However, it is also a fact that most of the relics have a tea master’s flavor in terms of style, and it is believed that this type of wari-gatai was mainly fired in the early Edo period (1603-1868) during the Dumoepo Wakan period in Jinju and Gimhae, near Busan, or in some cases, a little later, at the Wakan kiln in Busan. In the “Chado Shodenshu,” there is a description that says, “The tea bowls with a high plateau split come from the time of Lord Hideyoshi’s entry into Koryo, and they are made to look like Furuta Oribe’s, so they have become a famous item. The reference to the time of Lord Hideyoshi’s entry into the Koryo Dynasty and the reference to Oribe Furuta as a masterpiece are reasonable and understandable from the perspective of the period and Oribe’s tastes. The Wari-takadai in this area was probably known to tea masters even before the Bunroku-Keicho War, but it happened to be the occasion for a new trend in Oribe’s taste, and Wari-takadai suddenly became popular after the war, and pottery made in kirigata style also began to be produced.

The name “Waritakadai” is mentioned in an old document in the “Honkou Kokushi Nikki” in an article on the Gohonmaru tea ceremony held on the 10th day of the 11th month in the 6th year of Kan’ei (1615), which says that the tea bowl “is Korai of Waritakadai, which is now in the possession of Doi Otatagashira-dono and formerly in the possession of Fukushima Daishu-dono”, which probably came from the Korean War. It is thought that the unique style of Oribe’s work was a perfect match for warlord tea masters who were fascinated by Oribe’s tastes. It is also interesting to note that Fukushima Masanori, one of the most famous tea masters along with Kato Kiyomasa, was the owner of the aforementioned Waritakadai. Because of this connection, wari-takadai were highly prized by the feudal lords, and are listed in the “Gan-nin Meimono Ki” published in 1801 (although some of them may have been cut forms).

) Because of its origin and dignity, wari-takadai was valued along with wells, and was said to be an indispensable part of a Daimyo’s tea bowl.

Goshomaru

As stated clearly in “Mi-chisa” (A book of the Imperial Court), “Goshomaru Gohonteya, Oribe type”, this is a Gohon teabowl favored by Oribe. It is a so-called Oribe Gohon, and together with a certain type of split-topped stand, it is the oldest Gohonte of its era. It was fired at Kinhai, near Igayama, in the early Edo period (1603-1868) during the period of Mameurawakan, and is a type of Kinhai katate, also known as Kinhai goshomaru. It was later called Honte Goshomaru, in contrast to Gohon Goshomaru, which was made at the Wakan kiln in Busan.

According to legend, the name “Goshomaru” originated when Shimazu Yoshihiro had this type of tea bowl fired in this area during the Joseon Dynasty and presented it to Hideyoshi on the warship Goshomaru. The name “Goshomaru” is also found in a document of the Tensho period related to Shimai Munemuro, a wealthy merchant in Hakata, as a trading ship with Korea.

The overall shape of the Goshomaru is highly distinctive, with a shoe shape in the style of Oribe, a thicker construction, a bead-rimmed mouth, a taut body, and a taut waist, and a spatula called a tortoiseshell spatula on the waist. The base is large, with a large, earthen base and a polygonal shape with a spatula cut out of it. As can be seen, this is a very varied and highly technical piece, and the workmanship is very formidable. The body has a fine, vivid stripe of pull marks, and the reddish color of the Gohon style, a characteristic of Kinkai kote, appears on many parts of the body. In addition to plain white, Goshomaru also comes with a hand with a black brush pattern, but the latter is much less common. Tea masters call the plain white hand “Goshomaru” and the black-brushed hand “Furuta Korai” to distinguish them.

The tea bowls that are called “Furuta Korai” by the Oribe family, which tend to be plain, are especially famous as Goshomaru’s original tea bowls, but the outside of its base is irregularly round, and the inside is pentagonal with a spatula shaving. It is likely that Goshomaru’s polygonal tea bowls were modeled after this one, and were later formalized.

Irabo

There is a theory that the name Irabo is a place name, but there is no firm evidence to support it. The name “Iraho” is already found in an article from the 3rd year of Manji in “Bitaniki,” so it is clear that it was already in existence in the early Edo period. In the “Mishisa,” the characters for “de abao” and “irabo” were already marked, and by the Genroku period, it seems that the use of these characters had been settled on. In the “Mishisa,” it is written, “Irabo to irarabo to araki me no nari mono ya.

The common characteristics of Irabo handkerchiefs are that they are made of iron-rich sandy clay, that they are slightly thicker and deeper in shape, and that they extend straight from the waist to the mouth instead of being stretched at the body, which gives them a wide-open mouth. The sandy base not only adds the taste of “sabi” but also makes it easy to serve tea, which is the purpose of a tea bowl.

Irabo is the most prominent of the Jakubi ware, but a closer look reveals that it is not only technically but also design-wise, extremely sensitive.

When we take a closer look at it, we can see that it is extremely well-designed, both in terms of technique and design, and it has the perfect feeling for the tea ceremony. In terms of the design techniques such as kiri-wari, beveling, inner brushwork, one side of the body change, nail engraving, etc., and also in terms of the clear classification of the types such as Senkusa Irabo, one side of the body change Irabo, nail engraving Irabo, bowl-shaped Irabo, yellow Irabo, etc., we must assume that this was clearly made in kiri-shape to meet the taste of the tea masters. In other words, it is a kind of Gohon tea bowl.

In fact, Mr. Nomori Ken, a former Korean governor-general, has excavated fragments of iraho in the kiln site of Chang-gi, near Busan, which have been clearly proven by the discovery of fragments of iraho in place of inner brushes and katami (one side of the body). The style of the work suggests that it was made in the early Edo period (1603-1867), probably during the period of the Dumoepo Wakan (now part of the Mukden Palace). It is customary for tea masters not to allow even the slightest flaw or mending to be made to Irabo.

Tea masters divide Iraho into Ko-iraho, Chikusa Iraho, Katajimawari Iraho, Nugibori Iraho, Bowl-shaped Iraho, and Kiyo Iraho.

Old Iraho

Ko-Iraho is a type of ko-Iraho, along with kata-migiwari Iraho, and is considered to be a superior kata-migiwari hand, although most of its style characteristics are similar to those of the kata-migiwari hand, and the “Koryo Chawan Yajiroku” and others consider it to be the same hand.

The name “Chigusa Iraho” is derived from the name of the bowl that came from the Hirase family (Chigusa-ya), which is said to be the original poem, and which was formerly owned by Prime Minister Chigusa.

Katajimigae Iraho

This bowl is a type of old Iraho, but the name is derived from the fact that the Iraho glaze and the well glaze are separated, which is a major feature of this type of bowl. The mouth rim is slightly warped at the edges and is usually held down in one place with a sharp cutout to form a gutter. The body has a fine stripe pattern and a half-turned brush pattern on the prospective side, and it is a rule to always look at the brush tip. There is usually a beveler or a stone haze. The stand is well-shaped, with bamboo joints, and the width of the helmet is round and large. The width of the helmet is round and large.

The hand of the kata-miwawari is especially prized among Ko-Iraho, and is a representative of Ko-Iraho. The glaze is also careless and not too light, which is very pleasing to the eye, and the overlapping glaze is a natural scene. The sharp cutouts and the prospective single brushstrokes make a very clear impression, adding a kind of bright elegance to the austerity, and truly expressing the taste of flowers in a sakurabi-style ware.

Nail engraving iraho

This name is derived from the whorl-shaped carvings, which appear to have been carved with a nail, on the inside of the base. The work is generally tough, as the name implies, and is almost the same in style as the old Iraho, but there are some differences in characteristics, so it is separately classified as nail engraved Iraho work.

The base is a reddish-brown, sandy clay, usually with a hint of stone, which is used to create the appearance of stone haze. The rough, sandy surface is a characteristic shared with persimmon calyxes. This texture makes it suitable for tea ceremony. Not only is it suitable for making tea, but it is also full of the tea ceremony taste in terms of texture and appearance, and is indispensable for sakubimono (tea ceremony). I would like to think that the tea ceremony masters had the intention of using rough clay with sand in it instead of strained clay.

Although this hand does not have a cutout at the edge of the mouth, it has a less formal mountain path, and the beveled edge is pleasing. The shape is a little tauter than the others, and the shaved hem and side decoration add variety. The iraho glaze is applied thinly and unevenly to the base of the bowl, but as the tea masters say, “iraho yaku hitsupareteka,” which is a characteristic and highlight of the nail carving technique. The combination of the various shades of blue laver-like glaze and the reddish tones of the ground gives it a complex, subtle, and indescribable coloring that is deeply appealing. The glaze is moist and lustrous throughout, but the reddish tones are particularly strong in areas where the glaze is almost completely faded, and the surface is shiny. The inside and outside of the bowl have fine, vivid stripes.

The base is not made of bamboo and is flat with a cut in one place, but this cut base is one of the promises of the nail carver, which is different from other Irabo pieces. The inside of the stand is flat without the width of the helmet, unlike the old Iraho and katamikawari, and has a spiral carving as if it were carved with a thick nail while being aggressively pushed at an angle. This is the most distinctive feature of nugibori hand carvers, and the reason for the name “nugibori.

In the old days, nail carvings that extended across the base of the table, as in the case of Genetsu Iraho, were called “honte nail carvings,” and were highly valued.

Nugibori te are rare, but a few of the most outstanding examples are very similar, not only in style, but also in the bent nail-carving technique. The nail-carving hand is also probably the work of a tea ceremony master who fired it in the kiln of the aforementioned Shoki.

Bowl-shaped iraho is also a type of nailed carving hand, but the name is derived from the shape, and there are very few of them.

Yellow Iraho

This name is derived from the yellow glaze, but there are two types of bowls, the main hand and the ordinary hand, with the former being the most famous. The production process is generally similar to that of Ko-Iraho, but the base is whiter. It is slightly warped at the edges and has a cutout at the mouth rim, which is the promise of this type of bowl. The base has fine stripes, and the glaze has a “hitsupareka” technique, which varies in shading and is pleasing to the eye. The bebera of the mouth rim, the sandy grain of the prospective surface, and the bamboo joints are all part of the promise.

The Korean Iraho type was copied from the Ko-Iraho type and fired at the Wakan kiln in Busan. The inner printing, mountain paths, bevels, etc., are just like the type, but the plateau and other parts are poorly made at first glance and are of a later period.

Carved Mishima

This type of potter’s wheel has the Mishimate style, so named because of its carved hinokigaki (cypress fence) pattern. Each hand is of a uniform shape and diameter and is shallow, with a two or three-tiered band of carved cypress fence patterns running from the mouth rim to the interior and exterior. The base is covered with a translucent glaze that extends to the base, leaving no earthy appearance.

The base is a fat clay with a high iron content, and depending on the firing conditions, the color can be reddish or bluish, and the blue fire in the reddish color is particularly pleasing. The prospective face has about eight eyes, and the inside of the base is covered with a crepe crepe in the style of totoya (a type of crepe).

The flower shape is usually only on the prospective side, but rarely on the outer side, which is called the outer flower. The number of outer flowers is usually 16. Gaikate is highly prized not only because it is extremely rare, but also because it has a superior workmanship compared to ordinary carved mishima.

Among the well-known Gaikate pieces are those from the Hirase family, those from the Mitsui family, Yaegaki from the Yakura family in Kyoto, Takeya Muneyuki’s piece, and Hotaru from the Otsu family in Ise.

Compared to the free and spontaneous style of Mishimate, the carved Mishima style seems to be more formal, and the patterns and techniques are not seen in the traditional Mishimate style, which suggests that this type of bowl was fired in a kiln near Busan by a tea master in the early Edo period. It is thought to have been fired in a kiln near Busan by a tea ceremony master during the period of Dumoepo Wakan in the early Edo period, but there is also a theory that a kiln near Yangsan (Gyeongsangnam-do) was used.

Unkaku (cloud and crane)

This type of inlaid celadon porcelain hand is often called “cloud and crane” because of its many cloud and crane patterns, and the name is also found in “Michisa”. There are many tubes. However, there are various types with different styles among them, and tea masters have divided them into kounkaku, kyogen hakama, hiki sheath, Joseon unkaku, and others. The two main types are those made in the Goryeo Dynasty and those made to order by tea masters in Busan or nearby areas in the early Edo period (mid Yi Dynasty).

Old cloud cranes

According to tea masters, this term refers to the oldest and most unrefined of the Joseon ungak, including some with wooden sheaths and others with square stamps on the front, and the new and old are mixed indiscriminately. This was not surprising for tea masters of the Edo period, who had not yet done their research. Today, however, it goes without saying that some adjustments must be made to the names to make the period clear. However, since the name “Kounkaku” is a traditional name in this field, it has become the trend in recent years to use it as it is, but to limit the tea bowls to those from the Koryo period.

One of the most famous tea bowls of this type is the kyogen hakama. It has white inlays on the top and bottom of the tube and a white inlaid circle with black on the front and back of the body, which resembles the crest of a kyogen hakama, hence the name.

The name “Kyogen Hakama” is also found in “Tsuda Munenori Chayu Nikki” (Diary of a Tea Ceremony), which describes a tea ceremony held by Ishida Mitsunari around Keicho period, and its origin seems to be old. The deeper version of this kyogen hakama resembles the wooden sheath of a tea mortar, so it is called a hikigi sheath. The most famous example is the one owned by Rikyu.

Kyogen Hakama’s handles are thick and slightly heavy, with a blue-gray glazed surface that is pierced with a blue-gray glaze, and the glaze is thick and extends to the back of the hakidai, which is a sandy hakidai. The thick glaze extends to the back of the base, and it has a high sandy pedestal. The style of this piece is not very elegant, and the sandy pedestal suggests that it is an inlaid celadon of the late Goryeo period. The tea ceremony book describes it as “quiet.” The wabi-like appearance was probably favored by Rikyu and other masters of the tea ceremony. It is said that the kiln where this hand was fired was in the Gyeongsangdo area, and Mr. Ito Ki-o mentions Goryeong and Gyeongju in Gyeongsangbuk-do Province. Kyogen Hakama is said by tea masters to have been a teacup used for drinking yakyu, a Korean medicine made from tartar, but there is also a theory that it was a tea bowl for otecha, a tea ceremony popular in the late Goryeo period.

Another well-known example of kounkaku is the Segawa family’s tortoiseshell tsutsu, which is inscribed with the name “Mishima” on the box. It is a thin, high-quality piece, older than Kyogen Hakama, and is thought to have originated in Gangjin, Jeollanam-do (South Jeolla Province) or Buan, Jeollabuk-do (North Jeolla Province), where the Kamite inlaid celadon ware was produced. Older Kamate pieces usually have a stone eye color.

Although they are commonly referred to as Koryo tea bowls, they are usually from the early to mid Yi Dynasty, i.e., from Muromachi to the early Edo period, and the only piece actually from the Koryo period is the Kounghak (narrowly defined) mentioned above. In fact, there are very few Goryeo inlaid celadon wares that have been used as tea utensils, but in addition to this Goyunghak, other famous examples from the Goryeo period include incense burners, square vases, and cylindrical vases inscribed by an elderly woman, all of which are rare masterpieces. Kyogen Hakama is sometimes used as a generic term for Kyogen Hakama instead of Kounkaku, but it is rarely used as a generic term these days because of the confusion between old and new Kyogen Hakama.

Kumotsuru

Among those that have been called Kounsaku in the past, those dating back to the middle of the Yi Dynasty (early Edo period) have recently been distinguished by this name.

In the period of Mumo-po Wagwan, works imitating this technique were fired at or near the Wagwan kiln in Busan, with the addition of a cut shape at the order of tea masters. Compared to the original kounghak, there are some differences in the production process, glaze tone, and various other aspects. First of all, the general impression is that the Goryeo period Kounhak has a refined and naturalistic appearance, whereas the latter has an overdesign and intentional aspect that cannot be removed.

The shapes of many of them are also different from those of the Kounhaku, such as the taut hem and large wari-takadai, which show a clear difference from the clean cylindrical shape and ring-takadai of the Kounhaku. The glaze is thick and uneven, and the glaze tone has a peculiar moistness, and many of them have a fire-shift effect. This period was just when Oribe’s taste for Oribe was fading and the “heuge” style was greatly appreciated, and the unusual design of this cloud and crane tube may have been influenced by this. The cloud-and-crane pattern differs from that of the Koryo style, and the overall impression is one of restraint.

In short, this hand is considered to be a kind of Gohon tea bowl, and its relics are treasured as a masterpiece.

Gimhae

This bowl is named after the Kimhae kiln near Busan, but there is a certain promise for the hand called “Kimhae tea bowl” (“Kimhae is a bowl made before 40 years, fired in a place called Kimhae” in “Kanei Teikan”). Kinhai is a kiln that is characterized by its hard hand, and the oldest tea bowls fired here are Goshomaru, for example. The Goshomaru is the oldest tea bowl made in this kiln. The Kinkai tea bowl was made after Goshomaru, and it is clear from its promise that it was made in the style of a tea master’s cut. It is thought that they were made by order after Goshomaru, also during the period of Mameurawakan.

The tea masters further divided Kinkai teabowls into two types according to their characteristics: honte and koban-katauri.

Honde

Honde are extremely rare in the world, and Seiohbo is a representative example. The mouth is thinly made in the shape of a peach, or Suhama, with a fine stripe of the drawn line on the inside and outside, and from the waist down, a slight reddish color, a characteristic of the Kinhai kiln, is seen. The base of the bowl is of the earthenware style and is high and sturdy. The base is high and sturdy, and is broken in one or two places. On the body, there is no cat scratch on the main hand, but there is a strong Kinkai inscription in the form of nail engraving on the waist.

Although it was originally a kind of Gohon teacup, it is more robust than later Gohon kinkai, and is full of vigor and dignity. The glaze is also very rich, and the engraved inscription of Kinhai has a power and flavor appropriate to the bowl’s character.

KOBAN-SHIRI

This type of vase is later in age than the main type, and is so named because of its koban-shaped mouth. The body is thinly made and has a hinokagaki-style nekagaki (cat’s scratch) pattern. The high stand is open on the outside, and is often split. The reddish color is pleasing to the eye. The glaze tone is lower than that of the original.

Gohon Tea Bowl

Gohon Tea Bowls were made by sending Gohon, or Gotehon (cut forms) from Japan to Joseon and having them fired at the Wakan Kiln in Busan and other kilns in the area.

The original meaning and scope of Gohonte are clear, as it is written in “Mishisa”, “Gohonte Rikyu Oribe Hon, this is a bowl that was sent to Koryo after receiving a copy of the original from a court official and having it made to order, and then sent to Honcho like the original”. The original meaning and scope of the Gohonte are clear.

It is not necessarily inconceivable that before the Bunroku-Keicho period, during the reign of Hideyoshi, a request for tea bowls was made to Joseon via Japanese envoys or merchants in the form of kirike-gata, in view of the Koryo tea bowl boom of the time. What the above-mentioned “Mishisa” mentions about the Rikyu Gohon is not necessarily something that should be dismissed as ridiculous or even laughable.

It is likely that there are a few tea bowls in the so-called Korai tea bowls that were cut by tea masters of the time, including the Rikyu Gohon, but no specific clues can be found to point this out. What can be clearly said is that they are from Oribe Gohon, and Goshomaru is a representative tea bowl. In this sense, Goshomaru is the oldest Gohon bowl. This tea bowl is called Furuta Korai because it belonged to Oribe, but since Shimazu Yoshihiro was a student of Oribe, it is safe to say that he had it made in the region during his zaisen period, as legend has it, after receiving a cut form from his master. There may be similar pieces of the same time, so-called “numbered objects,” and there are also pieces that were created later, as indicated by the slight change in style. In any case, it is obvious that these bowls are based on a special promise, such as the shape of a shoe. It is a characteristic of Gohon tea bowls to faithfully adopt the various promises of the kirigata, and it is only natural that the tea bowls born from them should be katamono tea bowls.

The wari-takadai, which became popular after the Joseon War, was mostly inspired by the original Joseon work, but it is said that Oribe was the first to focus on the wari-takadai, and the “haeuge” feeling of the unusual wari-takadai, such as in ritual vessels, was exactly what Oribe liked. The popularity of wari-takadai among warlords was probably due in large part to the recommendation of Oribe, who had many of them as apprentices. Orders for wari-takadai were placed in response to this momentum, and they were probably fired not only during the war but also afterwards, but most of the pieces clearly show that they were to their liking at first glance. In general, they seem to be based on Oribe’s preference for “heuge.

In the Fushimi Prime Minister’s Meeting on February 29th, Keicho 4, “Sotan’s Jiki,” there is an entry that says, “Tea bowl is Korai, Koyomino hand, Hizumu, Shiki (note high table) wo Yotsunikizamigyou, Heuge mono ya,” which is a split table, but we cannot tell from the article alone whether it is an original Korean piece or a favorite piece, but it is likely that it is a piece that Mori Terumoto proudly brought back from Korea. It seems that Mori Terumoto proudly brought it back from Joseon, and Kamiya Sotan also expressed his appreciation for it. Sotan happened to have attended a tea ceremony of Furuta Oribe in Fushimi the day before, and at that time, after the death of Rikyu, Oribe was at the height of his popularity, and Oribe’s taste was booming.

Terumoto’s wari-takaidai also seems to have suited Oribe’s taste. The word “koyomite” is used not only for Mishima but also for Ishida Mitsunari’s kyogen hakama, so it may refer to an inlaid pattern. If we assume that the wari-takadai of Terumoto was made by clouds and cranes, then it can be said that, like Goshomaru, the cloud-and-crane hand with the same intention of making it was already developed during the war. If this Waritakadai is considered to be Untsuru, then, like Goshomaru, the intentional Untsuru hand was also developed during the war.

Both wari-takadai and untsuru have their original songs in the original Joseon works, and they are so to speak, “adding their own favorites” to them, but since untsuru still has various points that can be called a certain promise, it can be called a gohoncha-bowl. (Although it can be said that each piece is a “Gohon” tea bowl made according to its own cut shape, there is no doubt that it is a custom-made tea bowl made according to the cut shape of the customer’s preference.

After the Bunroku and Keicho Wars, diplomatic relations between Japan and Korea ceased for a while, but with the conclusion of peace in the 12th year of Keicho, the temporarily closed Wakan was established in Dumoepo, Busan. According to Asakawa Hakunori, in 16 Kan’ei, the shogun Iemitsu ordered tea bowls to be ordered, so he brought in potter’s clay from Hadong and Jinju in Gyeongsangnamdo, invited potters, and built a kiln outside the Wagwan on the Joseon side.

The IRABO and CHOKU MISHIMA are “clearly recognizable as Gohon tea bowls,” but the IRABO itself was fired at the Changki kiln at least before that time, since a copy of the “Irabote” is already mentioned in an article from the 3rd year of Manji in “Bi Mo Ki” (Bimoji).

The careful attention to detail seen in Irabo was born from the tastes of skilled tea masters, and there is no doubt that it is due to the cutting style of Enshu and other tea masters who were prominent in the tea ceremony. The fact that it is not at all frivolous and has a relaxed old style is due to the skill of the traditional local potters. The tea masters’ designs, such as the intentional kiri-wari, inner printing, one side of the body change, and nail engraving, are not only not bothersome, but even create a clear effect, which is a great attraction. In Irabo, in particular, the combination of both the artistry of the artist and the design of the tea ceremony utensil are perfectly blended and mellowed, creating the feeling of sipping a fine, mellow sake. Although small in size, I greatly admire this work as a wonderful synthesis of the arts of Japan and Korea. In terms of tea ceremony, this is the best example of the Gohon tea bowls that were popular in the Enshu period.

The Nezumi-Shino, which has a hinokigaki pattern in the style of carved Mishima, was suggested by the expression of inlaid Mishima, but its design was inspired by the same taste, and it can be said that it is a testimony to the age of carved Mishima.

The persimmon calyxes and to-Ya, especially the honte to-Ya, have a variety of promises, such as the cut-around, which can be considered to be a Gohon teacup. In fact, they can be considered to be Gohon teabowls. The clay for both types of bowls is also from the Busan area, and they were probably fired in kilns near Busan or in kilns in Wakan during the Dumoepo Wakan period.

Wu wares are also mostly from this period, but there are some new and old wares among them. In short, while all of them are Gohonte in shape, the later wares, which were clearly fired in the Wakan kiln, are called Gohon Wu ware.

Kinkai is also clearly a Gohon teabowl with a cut shape, and is considered to be made in this period, but the Honde Kinkai, although a favorite of mine, is indeed a strong piece and has an ancient character, and seems to belong to the early stage of this period.

In a sense, the Gohon tea bowls of this period comprise the majority of the traditional Koryo tea bowls, and also contain the deepest part of their charm. This trend is due, in part, to the fact that Korai tea bowls were increasingly in demand as the tea ceremony became more popular and the taste of tea masters shifted from coarse to dense, i.e., from Oribe to Enshu, and the existing ones were neither sufficient in number nor satisfactory in taste, This is thought to be the result of a shift in taste from the weaving style to the Enshu style. Certain types of wells, well sides, buckwheat noodles, and parts of katate, go-untsuru, go-kumagawa, etc., are also thought to have been fired during this period, and a huge amount of Gohon tea bowls were imported and spread throughout the world of the tea ceremony, known among tea masters since ancient times as Toujin-matari, O-matari, Ogifune, Enpo-4-nen-matari, and so forth.

After the restoration of diplomatic relations between Japan and Tsushima, the Soke of Tsushima was in charge of trade, and the orders for Gohon-tea bowls ordered by the shogunate were also under the control of the Soke. The Soke built a kiln inside the Wakan, and various types of tea bowls were fired by Joseon potters under the direction of Japanese potters, using clay from Gimhae, Jinju, Hadong, Ulsan, Milyang, and other regions. However, this kiln was eventually abandoned in Kyoho 2. Compared to the prosperity of tea bowls during the early Wagwan period (Keicho 12 to Enpo 5, about 70 years), the late Wagwan kilns did not seem to do so well, and the tone of the works became lighter, and the so-called Gohon-teawan style, which was just a pretty, unimpressive, and conventional style, was used. The style of the works became lighter and more conventional, the so-called “Gohon-chawan” style, which is just a neat and unimpressive style.

The works of the Wagwan kiln during the 80 years of the early and late periods are the so-called Busan Gohon, or Busan kiln, and are also commonly referred to as Gohon tea bowls by tea masters, but even though they are from the Dumoepo period, it is difficult to determine if the works from the late period are actually from the Choryang period, and we can only determine the approximate period based on the style of the works. It is difficult to determine the approximate period by the style. In particular, Busan kiln wares are characterized by a reddish mottling on the skin, which is often seen on Gohonte wares and is commonly referred to as Gohon.

The Busan Gohon include the famous Gohon Tachitsuru, E-Gohon, Suna (hand) Gohon, Gohon Goshomaru, Gohon Kumotsuru, Gohon Mishima, Gohon Kinkai, and Gohon Hanshitsu.

Gohon Tachitsuru

This is the most famous of the so-called Gohon teacups, and the word “Gohon” is like a byword for “Tachitsuru”. Among Gohon tea bowls, this Tachitsuru and E-Gohon have been separately prized. This is because they were ordered by the shoguns during the Edo period, and therefore were highly esteemed.

The name “tachitsuru” (standing crane) is derived from the black-and-white inlays on the front and back of the body, which are pressed in the shape of a standing crane. This pattern is said to have been painted by Shogun Iemitsu for Hosokawa Sansai’s celebration of his death, and became a preparatory sketch for the painting. It has a thin cylindrical shape with a slightly bowed mouth rim, a standing crane design on the front and back, and a three-split base. There are fine stripes on the surface with a reddish hue, and some blue fire patterns. It is extremely rare.

The Tachikaku tea bowl was especially appreciated by tea masters, and copies of this bowl were often made to order from Joseon. In contrast, the first one is called “Honde Tachikaku” to distinguish it from the second one. The Honte is by far superior in every respect, including the yugi, tachikaku (standing crane), glaze tone, and glaze glaze buildup, but the difference is clearly shown in the strength of the wari-takadai (split height stand).

E-Gohon

Gohonte with simple dyed and painted decoration, usually made of white clay. The base is usually white clay, with blackened gosu. The most famous is the pine, bamboo, and plum hand, of which there are only seven new and various types. There are also landscape, bamboo grass, bracken, wisteria, chrysanthemum, and whirlpool paintings. Some of them are said to have been painted by Tanyu or Tsunenobu.

The hollyhock design is from the tea bowls used by the Shogun when he served tea to the lords and ladies, and the “Kan-eiji” mark is from the tea bowls of the same temple. The other Gohon Mishima bowls are thinly made, with a distorted mouth rim and a split high rim, and their design is clear. The pattern of the hair is completely different from the original Mishima, and is in the style of yorokezima. It is said to have been made by Genetsu or Shigezo, who came from Tsushima to Pusan and fired it at the Wakan kiln in Pusan.

The name “Hanshi” was given to a judge (a Korean interpreter), who brought this bowl with him when he came to Japan in the early days of the Joseon Dynasty. Most of them are Gohon tea bowls, thinly made, with a light red base and a translucent glaze that has a slimy feel. The glaze has a sandy finish, and the mouth has a peach or suhama shape.

From year to year, the head family of Tsushima dispatched officials to preside over the Wakatate kiln, and some of them made tea bowls themselves, including Oura Rinsai, Nakayama Izo, Funabashi Genetsu, Nakaniwa (Abiru) Shigezo, Miyagawa Doji, Miyagawa Dozo (Kodoji), Matsumura Yaheita and Hirayama Iharu, among others, Genetsu and Shigezo are especially well known, and both excelled at Iraho, and both Genetsu and Shigezo are mentioned in “Michisa”. Genetsu is famous for his nail carving, and many of his works have a formidable style, extending beyond the kodai to the body.

On the other hand, Shigesan’s work is thinner, with a low kodai, and the inside of the kodai is rolled up in a whirlpool, with a brush on the front edge as promised. It has a stylish look and is much appreciated in the tea ceremony.

The Soke often had Gohon tea bowls made for the shogunate since the opening of the Busan kiln, but after the kiln closed in Kyoho 2, a kiln was built in Tsushima and tea bowls modeled after the Busan Gohon were fired (Hirayama Iharu opened a kiln in Shiga in Kyoho 10). This was the Taizhou kiln, and its tea bowls are called “Taizhou Gohon. After the Taishu kiln ceased to exist, it was reopened at the end of the Edo period, and the bowls that were made according to the taste of Kobori Sochu and others are called “Shin Gohon”.

Korai

Koryo tea bowls are called “Koryo” by tea masters because they are hard to find. Famous examples include the Araki Korai from Rikyu and Araki Dokaoru, the Hakuo and Toukin from Shaoou, the Evil Korai from Enshu, the Iibitsu Korai (Eininin tea bowl), and the Korai color change, which seems to include some Gohon tea bowls.

In addition, there are other types of bowls called by their glaze, such as Kaki Korai and Yellow Korai.