Well, well side, buckwheat, rain leak, kohiki, hard hand, egg hand

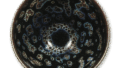

Tea bowls made in Joseon, such as wells, rain leaks, kohiki, totoya, mishima, hakeme, kureki, and gohon, are commonly referred to as Koryo tea bowls.

Koryo tea bowls have been loved and cherished by tea masters since ancient times, and their ethereal and lonely appearance deeply attracts people’s attention. Although there are many Koryo tea bowls that have been excavated from Korea in recent years, the majority of them have been handed down to our country and are now found only in our country and rarely in other countries.

The beauty of Koryo tea bowls is best described by the old Chinese saying, “It is as if the whole is muddy,” or “It is as if it is empty in its deep storage,” and has a deep atmosphere like that of an old monk without color or fragrance. It is the great achievement of Japanese tea masters to have discovered the beauty of Koryo tea bowls, to have classified them in various ways, to have given them titles such as “great masterpieces” and “masterpieces,” and to have preserved them more carefully than jewels. It is a unique Japanese way of looking at ceramics to think that Koryo tea bowls are beautiful, and few Koreans or Westerners, who made these bowls, understand their beauty.

Even though they are called Goryeo tea bowls, there are not many tea bowls that were actually made during the Goryeo Dynasty. Most of them were made during the Yi Dynasty, but it is still not fully known when or where in Korea they were made.

It is believed that the beauty of Koryo tea bowls was discovered and they came to be used in the tea ceremony from the end of the Muromachi period to the Momoyama period. After the appearance of Shukoh, Shaowo, and Rikyu, Wabicha became popular, and soft and friendly tea bowls became preferred over hard and neat tea bowls, Korean tea bowls such as Ido and Mishima became more respected than Chinese tea bowls such as Tenmoku and Celadon.

The term “Koryo tea bowls” is not yet found in the “Kimidai Kangenjochoki” compiled by Aami, which contains an inscription dated 1511. The first time the term “Koryo tea bowl” appears is in “Tsuda Sotatsu Chayu Nikki (Diary of Sotatsu’s Tea Ceremony),” which mentions “Kaurai chawan chatsu” in the Sorikai dated December 12, 1549. In the same book, Sotatsu’s own meeting on January 7, 1554, also records the use of a Korai tea bowl, and in the “Chagu Biyu Shu” edited by Ippuken Sokin with an inscription of the 23rd year of Tenbun, a Korai tea bowl is also mentioned.

In the “Kakuso Jinki” with an inscription in 1564 (Eiroku 7), there is an article that reads, “Sukiyori at that time had become like Karamono Hailanu,” and in the “Yamakami Souji Chasho” with an inscription in 1588 (Tensho 16), “Regarding Sobetsu Chabon, Karacha-bowl is thrown away, and in this generation, Korai tea-bowl is now ware to Seto tea-bowl and below. The tea bowls of the present day are Korai tea bowls and Seto tea bowls. This indicates that from around the time of the Tenmon period to the Tensho period, along with the popularity of Wabicha, hard tea bowls such as Tenmoku and celadon gradually fell out of favor, and soft Korean tea bowls such as Ido, Kobiki, and Soba became more and more popular.

The Joseon tea bowls that began to be popular from the end of the Muromachi period to the Warring States period were first called Koryo tea bowls, and then the words “Ido” and “Mishima” began to appear in the tea ceremony records. Koryo tea bowls were classified into Oido, Koido, Ido Koganiri, Ido Waki, Soba, Kohiki, Amebake, Kote, Jyute, Tamagote, Hakeme, Kumagawa, Hanshi, Kureki, Todoya, Kaki no Obi, Iraho, Wari Takadai, Brush Wash, Kinkai, Kumotsuru, Kyogen Hakama, Carved Mishima, Goshomaru, and Gohon, and further subdivided into various categories, which were given various names in the Edo period. It was not until the Edo period (1603-1867) that various names were given to them. In the Edo period around the time of Enshu Kobori, there was still no such detailed classification as today, and it was not until after Kansei that Korai tea bowls were subdivided as they are now, and I have not seen any old box descriptions for Aoido, Tamagotate, or Soft Te.

Among Korai tea bowls, there are various types that do not belong to the previously mentioned categories. For example, there are teacups in the style of a well that are neither a well, nor beside a well, nor by the side of a well. There are also teacups that are neither katate, ame-no-te, nor tamago-te, but are similar to these. Tea masters have called all of these Koryo tea bowls since olden times, and there is no mistake if we call them Koryo tea bowls, even if we do not know their names.

Koryo tea bowls can be roughly divided into two types: those that early tea masters such as Jukou, Shaoou, Munenori, Soukyuu, Souji, and Rikyu used as tea bowls out of Korean miscellaneous ware, and those that they ordered from Japan to be made into tea bowls as demand for Koryo tea bowls gradually increased and their relationship with the kilns in Korea became deeper. It is said that the demand for Korai tea bowls gradually increased and also became closely related to the Joseon kilns. If we assume that the earlier tea bowls are of the first category and the later ones of the second, wells, well sides, soba, kohiki, ameleki, hard hand, soft hand, tamagote, mishima, hakeme, kumagawa, hanshi, kureki, toto-ya, and kaki no obi are of the first category and Iraho, waritakadai, goshomaru, brush wash, kinhai, unkaku, carved mishima, gohon, gohon tachihaku, and painted gohon are of the second category. tea bowls of the second category. Tea bowls of the first category are daily utensils made on a familiar potter’s wheel in a haphazard manner, with a free-spirited and lively atmosphere. On the other hand, the tea bowls of the second category are somewhat deliberate in appearance and construction, and the later they are made, the thinner and more delicate they become, and they do not have the simple and dignified interest of the first category.

So, when did they start ordering Joseon to make tea bowls? No one has discussed this in depth yet, but it was probably around the Tensho period, when Koryo tea bowls were most popular. The second type of tea bowls ordered from Japan can be further divided into two periods: the period when they were ordered to be made at kilns around Busan, such as Gimhae and Changki, and the period after Kan’ei, when Japanese could no longer freely visit the kilns, and they were made in kilns built in Wakan. The thin tea bowls commonly called “Gohon,” “Gohon Tachihaku,” and “E-Gohon” are believed to have been made in the kilns of Wakan after the Kan’ei Era.

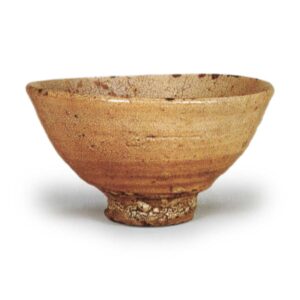

Wells

The well is said to be the king of tea bowls, and as the saying goes, “One well, two raku, three karatsu,” the well is considered to be the top of the line of tea bowls since ancient times.

Although Ido is a bold, large, and sturdy tea bowl, it is loved by many people because of its uninhibited style and warm and soft feeling.

The first time the name “well” appears in a tea ceremony diary is in “Tsuda Souryou Chayu Nikki (Diary of a Tea Ceremony)” in 1578 (Tensho 6), which mentions the use of wells in the “Yabu no Nai Souwa Kai” on October 25. The use of a well is also mentioned frequently in “Tsuda Sosho Chayu Nikki” and in “Sotan Nikki,” “Munehisa Imai Chayu Shokukan,” “Matsuya Nikki,” “Rikyu Hyakkai Nikki,” and “Koori Chakkai Nikki.

The word “well” came into common use around Tensho period, but the actual use of well tea bowls for tea ceremonies is older than that, and they must have been called Korai tea bowls before Tensho 6. Incidentally, in “Names of Well Tea Bowls” (Yakimono Hobby, Vol. 4, No. 3), Yukiyuki Fujita lists 18 wells that were handed down from Tensho or earlier: Kizaemon, Tsutsuizutsu, Sogyo, Aoraku, Fukushima, Sakabe, Ryukoin, Okorai, Hideyoshi’s Oido, Old Monk, Kamibayashi, Uji, Rikyu Well, Rikyu Small Well, Jumonji, Shibata, Matsumoto and Eiin. The next question is why these tea bowls are listed here.

Next, why did you name these bowls “wells”? There are many theories as to the origin of the word “well. The most widely accepted is that it belonged to a person with the surname “Ido” or that it was brought back from Korea. The second most popular theory is that the name “Ido” was derived from the name of a place in Gyeongsangdo called “Jangdo,” but I have heard that there is no such place name. In “Yuso-roku,” it is written, “Some people say that well tea bowls come from India, hence the name.

There are also many who believe that it was called “well” because of its deep interior like a well, but there is no clear evidence for this theory either.

Another theory, popularized by Kato Ryukaku, who served in the Korean Governor-General’s Office and was well versed in Korean affairs, suggests that the well was a glaze, or clay for clothing.

There are several other theories, but since there is no data available for the Tensho and Bunroku periods, there is still no established theory as to the etymology of the word well.

Next, when were wells constructed? One theory is that it was made during the Goryeo Dynasty. Yusaku Imaizumi, an old man, says, “These tea bowls are apparently so old that they are thought to be about 700 years old, or even more than 600 years old. (Koryo Chawan to Seto no Chajiryu [Koryo Tea Bowl and Seto Tea Container]), and even nowadays, there are people who think that the wells are miscellaneous vessels from the late Koryo period.

However, Koryo tea bowls were popular from the late Muromachi period to the Sengoku and Momoyama periods, along with the popularity of Wabicha, and if there is no record of them before the astronomical period, it is more reasonable to think that the wells were made in Joseon in the late Muromachi period. In Joseon, there is little custom of carefully preserving old things. It is difficult to imagine that daily utensils such as wells, especially fragile pottery, could have been preserved safely for a hundred years or even longer. It is also inconceivable that the pottery was imported to Japan at the end of the Goryeo Dynasty or the beginning of the Yi Dynasty, and that it was carefully preserved somewhere. It is likely that a large number of wells were made by Japanese tea masters at the end of the 15th century or beginning of the 16th century, and that a large number of wells were imported to Japan in the future. There is still no clear theory as to when the wells were created.

There is no dispute today that the wells are from Joseon, but where in Joseon were they made? Let me list the theories I have heard in order from the north,

(1) Gokuchi, Hamgyeongbuk-do (Shuichiro Kasai)

(2) Yeongheung Maepo, South Hamgyeong Province (Sagimura D)

Yeongbyeon, North Pyeongan Province (Narazaki Tetsuka)

Ieup, Jeollabuk-do (Jeollabuk-do)

(5) Suncheon, Jeollanam-do (Jeollanam-do)

Seonsan, Gyeongsangbuk-do

(vii) Yangsan, Gyeongsangnamdo (Mashimizu Zoroku)

(viii) Eonyang, Gyeongsangnam-do (Gyeongsangnam-do)

In addition to these theories, there is also the opinion that wells cannot be determined where they were burned, and that well-like objects were burned in various parts of Korea. It is true that well-like bowls were burned in Beijeongsan and also made in Namsun. Once, when I traveled to Hamhung in North Korea, an old man named Sagichon showed me a well-like bowl made in Yeongheung’s Yakpo, which was indeed very similar to a well. The bowls from Ie-eup in Jeollabuk-do and those from Seonsan and Goryeong in Gyeongsangbuk-do also look very similar to wells. However, upon closer inspection, they are different from the wells that have been prized in Japan since ancient times. Whether they are from Meimonte or Ko-ido, the clay, glaze, and style are almost identical, and it is difficult to believe that they were burned in one place and burned in another. It is also assumed that the pieces were made in the same kiln during the same period of time.

The late Mr. Ito Kio, an authority on Korean ceramics and a well-known collector of Korean antique ceramics who traveled extensively throughout Korea, once told us that the well was from Bo-ju, Gyeongsangnam-do Province. Mr. Ito had in his collection a tea bowl excavated in Bo-ju, Gyeongsangnam-do Province, which is exactly the same as the well in terms of the article, glaze, style, and tone of the kairagi (plum blossom skin). This tea bowl excavated in Jinzhou was compared with several wells that have been handed down in Japan, and the famous tea masters Morinosuke Mitsui and Hanzaburo Yokoi were also present to compare and study them. This tea bowl excavated in Jinzhou was left to Mr. Hanzaburo Yokoi, but unfortunately, it was destroyed by fire when the Yokoi family in Nagoya was hit by the war. I have not seen this tea bowl in person, so I cannot give my personal opinion, but I believe that it is the most worth listening to among the various theories. The late Mr. Asakawa Hakkyo, who is said to be the god of Korean ceramics and the most knowledgeable about Korean ceramics, once stayed at Zuisenji Temple in Kamakura and asked Mr. Asakawa many questions about Korean ceramics every day for about a week, and recorded his answers in his records. Asakawa Hakkyo also said that ceramic shards similar to those in the well were said to come from a kiln site near Jinju.

I would like to see a lot of people who are interested in the history of the world of the Internet and the history of the Internet. The most important thing to keep in mind is that the most important thing is that the person who is making the most of the time is the one who has the most time and the most money. In the view of the Joseon people, it is natural that all Goryeo tea bowls would be considered inferior, and a well may have been made at one of these three pottery kilns. Whether or not the well was made in Jinju can only be determined by future excavation of the old kiln site, but the most reliable theory today is the Jinju theory.

Wells are especially esteemed among Goryeo tea bowls, and it is not easy to obtain a single bowl, but the number of relics seems to be comparatively large. There are 19 kinds of Korai tea bowls in “Taisho Meikikan”, 230 pieces, and 75 of them are from Ido, which may be due to the fact that the emphasis is on Ido, but also because Ido tea bowls are comparatively more numerous than other tea bowls. In his book “Chakkou Dangi,” Okuda Seiichi Sensei lists 30 well-known bowls by Kizaemon, Kaga, Hosokawa, and others, and then lists eight wells whose holders are unknown: Tamagawa, Kashu, Miyoshino, Ido Shioge, Katamari, Himezatsu, and Kii, and continues as follows

Among the items called by the name of Koryo, there are many that are recognized as wells, and there are many well tea grudges that are not included in the book. There are many wells outside of the book. Although they are not included in the book, there are dozens of wells that I have seen recently at various bidding parties. Of course, these are not as famous as the great masterpieces. I believe that the number of wells still in existence must be in the hundreds.

We do not know the exact number of wells in existence today, but it must be no less than 200.

Traditionally, tea masters in Japan have classified wells and tea bowls of this type into Oido (one name: Meimonteido), Koido (one name: Ko-ido), Kogan-iri (one name: Kohibiteido), Aoido, Idowaki, and Soba, with Yusaku Imaizumi also classifying Fukibokuido, Zaramekiido, Soba-kasu, and Chushiroteido as well as Ido as tea bowls of this type. The well side and the buckwheat paste belong to the wells.

While Ido aside and Soba have their own characteristics and are distinguishable from Ido, the distinction between Oido, Ko-Ido, Ido Ko-Nuki and Ao-Ido is complicated in many ways, and there are quite a few that are difficult to distinguish from them. In terms of the meaning of the word, Oido is a large, high, and imposing tea bowl, Koido is a small, low, and cute tea bowl, Aoido is a blue bowl because of the high iron content and blue color of the base, and Ido Kogan-iri is a small, fine bowl with a thin glaze and fine penetration, but each type of tea bowl is not necessarily distinguished in this way. However, each bowl is not always distinguished in this way. This is probably because it was not possible to compare many wells by catalogs or photographs as is done today, and the distinction was made according to the discernment of the people at the time. For example, the old priests recorded in this volume, the Kamirin and the Nara wells, which were handed down from the Kuroda family, are large wells in terms of size, but they have the appearance of small wells due to their low elevation, so I have chosen to use the term “small wells. Ko-i-do is an application of ko-i-do, which should be interpreted to mean “small” rather than “old,” but the distinction between ko-i-do and ko-kuni-iri-do is not clear. In “Taisho Meiki-kan” (Taisho Meikikan), Part 7, the table of contents classifies it as konan-nyu, but the explanation classifies it as ko-ido, and kotaka is mistakenly classified as ido-waki. Koido and Kotaka in the former collection of Mr. Masayoshi Kato, which are classified as konkan-yumi, have the same nuki (penetration) as Meimonte no Ido, while Meimonte no O, Kiido, Ryukouin, etc. have much finer nuki (penetration). Even in a single bowl, depending on how thick or thin the glaze is applied, the penetration can be rough or fine, and I think it would be better not to make a distinction between “well” and “small penetration.

Aoido is probably called “blue well” because the iron content of the base is high, giving it a dull blue tinge when fired. Hoshu-an and Yama-no-i are indeed more bluish-black in color than Oido and Koido, and are therefore more suitable for being called Aoido. However, Shibata, for example, which is considered to be the best Aoido bowl, and Uji, which is generally understood to be Aoido although it is called Koido in the Taisho Meikikan, have glaze tones and colors similar to Oido and Koido, and are distinguished from Oido and Koido by the shape of their commonly known cedar form and the construction of the plateau, which is shaved with a spatula. The glaze color is similar to that of oido and koido. Also, among the tea bowls called “Aoido”, there is a white-skinned tea bowl close to the side of the well, so it seems that the distinction is based on the shape and workmanship rather than color. Yusaku Imaizumi also mentions the following tea bowls as belonging to the Aoido category: Aoido no Fuboku, Zarameki Aoido, and Chushihakute no Aoido.

Although I have long heard of the name “well fuboku,” I have never met anyone who has actually seen this type of well. In his book, “Korai Tea Bowls and Seto Tea Containers,” Imaizumi wrote, “The blown ink of a well is a kind of ink in a small hibite, and the ink color is blown out beautifully by the fire. The only thing is that the ink color has been blown out beautifully by the fire, and it has become an unexpected scenery. I once saw a tea bowl inscribed “Kujyu” with “Korai fuki sumi” written on the box. This tea bowl had fine mottled patterns of light gray color on a white ground in the style of a well, and was a kind of fire change caused by the slight iron content in the base of the bowl, not carbon deposits as described by Imaizumi and not ink color made of tea tannin as in the case of rain leaks. It is possible that there is a tea bowl called “well blown ink” somewhere, but it is not only extremely rare, but most people do not know about it.

The following is an explanation of the Zarameki well by Imaizumi.

The glaze of the Zarameki Ido is similar to the glaze on the side of the well. However, there is a large amount of sand in the clay, and when it is embroidered by fire, it appears in spots on top of the ratty glaze, making it feel very rough to the touch. In some cases, the glaze around the spots on the embroidered stones has turned white. In any case, the roughness of the glaze is what tea masters call a rough well.

According to this explanation, it seems to be a well-like tea bowl with a lot of fine feldspar grains on a slightly iron-rich base, and there are tea bowls that fit this concept in both Hokusen and Nansen. However, I have never come across a tea bowl with a box labeled “Zarameki,” so I would like to only introduce Mr. Imaizumi’s opinion.

In addition, Mr. Imaizumi writes that there is a well called “Chuhakute,” which refers to the Chuhakute that was handed down in the Kaga Maeda family, and is a tea bowl made of powder-coated cloth, not a well. I have heard that a gardener from Edo was invited to the Kaga residence, and from behind a glazed fence, he saw the lord of the domain holding a chujihaku at the edge of the garden, and mistakenly reported that the chuji was a well, which then spread to Edo.

I would like to add some personal comments on Oido, Koido, Aoiido, Idowaki, and Soba.

Oido Oido, also known as “hand well,” is one of the most respected wells in the area. It is a large, high, and imposing tea bowl, and can be said to be the “well” of the wells. The Taisho Meikikan lists Kizaemon, Kaga, Yuraku, Hosokawa, Matsunaga, Fukushima, Sakamoto, Okorai, and Ro-Monk as great masterpieces, but with the exception of Ro-Monk, they are all great wells made by great masters, and there are no great masterpieces among small or blue wells. But who in the world would have made these wells the “big names”? If Daimyo-mono is the same as Higashiyama Gomotsu, then the wells are the same.

If we assume that the daimyos are the Higashiyama Gomotsu, then there should be no daimyos in the wells. It was probably decided by the forensic experts around Enshu Kobori. Lord Fumai Matsudaira made a distinction between “great wells” and “famous wells,” and among the “great wells,” he designated those that were particularly outstanding as “famous wells. However, these days, all large wells are classified as meimonte, and the “Taisho Meikikan” does not make such a distinction.

Meimonotte wells are made of a sandy, refractory clay with a thick, transparent glaze that has penetrations on both the interior and exterior surfaces. The thicker the glaze, the rougher the penetration, and the thinner the penetration, the finer the penetration. Most of the wares are oxidized in the firing process, which gives them a loquat color due to the small amount of iron in the base, and some are slightly reduced and have a slight bluish tinge.

The mouth, body, and pedestal are all thick, giving the tea bowl a sturdy and massive appearance. Generally, they are characterized by their large size and high pedestal, but the side of the pedestal has been boldly scraped off with a single heel to form what is commonly called a bamboo joint pedestal. Most of them have a thick and strong potter’s wheel from the body to the waist, which is considered as one of the charms of Oido.

The inner surface is deep, and there is a tea bowl with a tea bowl and a tea sink, and some have eyes while others do not. Kizaemon, Kaga, and Hosokawa, which are said to be the three wells of Lord Fumai, all have no eyes, but this is because they were placed at the top when they were stacked and packed in the kiln. Most of them have five eyes, and of course, tatami-tsuki pots probably had five eyes each. After long use, the rough and highly refractory clay such as wells, the glaze peels off in pieces because the base and glaze are not fully melted together, and almost all the parts of the teacups called tatami-tsuki show the base. Most of them are blackish brown, but this is due to staining by tea stains, not the original color of the base material, as Imaizumi Roshi stated. In addition, wells are not fired tightly due to the rough clay and high refractoriness, so they are easily broken. Wells always have a vertical gutter around the rim, and many of them are also flawed. Nevertheless, since they are the most respected tea bowls, both tea masters and antique dealers do not complain about the defects of wells, and think that it is inevitable that wells have defects. Oido is characterized by the curling of the glaze, commonly called “kairagi,” on the high ground and the sides of the high ground, and is considered to be one of the highlights of Oido. One of the reasons for the kairagi is the roughness of the clay, and the kairagi usually appears only on the surface where the potter’s wheel has been used, and not on the surface where the potter’s wheel has been drained. The most important reason for the formation of wakashi plum bark is the use of shellfish ash as a solvent in the glaze. The reason why Japanese ceramics do not often have wakashi plum bark is because they mainly use wood ashes, and nowadays, lime. Shellfish ash has a strong acridity that causes the glaze to shrink.

Oido is an imposing, thick, large tea bowl, and although you would expect it to be heavy, it is surprisingly light in the hand. This is because there are two types of clay, heavy clay like Bizen and light clay like Hagi, and Oido is a light clay similar to Hagi. However, aside from the general lightness of the clay, not all oido has all of these promises and characteristics. Some of the glazes are grayish, some are white and not loquat-colored, and not all of them have a plum blossom skin or a thick wheel-thrown pattern. The pieces recorded in “Taisho Meikikan” do not have much umehana-hada (plum blossomskin) on them, as do pieces from the Nezu Museum such as Sogyo, Fukushima, Oo, Ryoji, Ryuko-in, Kokonoe, Kuju, and Oido.

When it comes to representative masterpieces of Oido, everyone mentions Kizaemon and Tsutsuizutsu, both of which were national treasures before World War II. Both were national treasures before World War II, and now Kizaemon is designated as a national treasure and Tsutsuizutsu as a national treasure. The Kizaemon has a fine figure and elevation, and the Tsutsuizutsu has a stately dignity. Hosokawa, Yuraku, Echigo, Sogyo, Tsushima, and Mino are known as the best bowls. In addition, Sakabe, Horai (Takeno), Matsunaga, Amoun, Xuxia, and Asakayama are also included in this volume. Of course, there are other famous Oido bowls, such as Kaga, Ken, Hon’ami, etc., but it is regrettable that they could not be included in this volume for various reasons.

Koido Koido is also written as “old well,” but this name was given because it is smaller than Oido, rather than because it is older. It is probably made at the same time and in the same place as the Oido in terms of the base, glaze tone, glaze color, workmanship, kairagi (plum blossom bark), and the tone of the penetration, etc. It is smaller than the Oido, and is probably made in the same place. However, they are smaller than Oido, generally flattened, and have a low, small base. However, there are also some tea bowls with a low base but large in size, such as those made by Rozo, Obama, and Ishiqimizu, so it is difficult to make a general statement.

The most famous bowl in Koido is the Rokujizo of the Sumitomo family. It is an excellent tea bowl with a slightly thin design, a mouth that is almost edge-sloped, a tightened base, and above all, a tasteful glaze tone. The other famous examples are the old monk, Bousui, Koshio, and Kamibayashi. Koshio is a cute well that is said to have been used by Lord Matsudaira Fumai. Koshio is a cute well said to have been always used by Lord Matsudaira Fumai. Koshio well has not as many relics as Oido, and the opportunities to see them are not as many as those of Oido.

Aoido The name “blue well” was probably given to this type of well because the iron content in its clay was high, and when baked, it looked bluish-black compared to Oido and Koido. However, among those called Ao-ido, some are loquat-colored, similar to Oido and Ko-ido, and some are white, similar to the sides of the wells. Today, the distinction is more likely to be based on the shallow and flat shape of the vessels, which are commonly referred to as cedar vessels. The body has little tension and opens in a straight line from the base, and the wide mouth is characterized by the tightness of the base, and the shape of the base is characterized by the shaving of the base with a single heel.

Shibata at the Nezu Museum, which is considered to be the best Aoido bowl, Hoshu-an in Kanazawa, which is blue-black in color and is very Aoido, Masuya, Unoi, Hayabusa, etc. all have this shape. Aoido is different from Oido in shape, especially in that its elevation is not as high as that of Oido. However, it is difficult to distinguish it from a small well, as in the case of the famous Uji well in Nagoya, where some people use small wells and others use blue wells. The Taisho Meikikan (Taisho Meikikan: A Guide to the Masterpieces of the Taisho Era) calls it a koido, but most tea masters call it an aoido. It is not clear who or when the name Aoido was first given, but it is not found in old tea ceremony books, and there are no old box notes. Its origin may be as early as the mid-Edo period. Aoido ware has a glaze similar to that of Oido and Koido ware, but the base material is different, and it is doubtful whether it was made in the same kiln as Oido and Koido ware. Where in Korea was Aoido made? The most commonly accepted theories are that it was made in Yangsan in Gyeongsangnam-do (South Gyeongsang Province), and that it was made in Dongnae in Eonyang. I have seen shards excavated from the kiln site in Dongnae, and although they look like blue wells, the glaze and the shape are different, and they were not produced in the same area as blue wells. I have yet to see any pieces of pottery from Yangsan and Hsik-yang that are said to be Aojido, and it is still unclear where Aojido was produced. In any case, it is reasonable to assume that it was made in the Gyeongsangnam-do region, as were large and small wells. Although there are more artifacts from Aoedo than from Koedo and Koedo kan-in, there are not as many as from Ooedo. The most famous Aoido bowls are Shibata at the Nezu Museum and Hoshu-an in Kanazawa, Shibata being of high dignity and Hoshu-an of deep taste.

Idowaki

Idowaki is not a well, but it is a tea bowl that is placed beside it, meaning that it is close to a well. Like Aoido, I have not seen any old tea ceremony records or old box notes, and the term Idowaki probably originated in the middle of the Edo period (1603-1868) or later. In Toda Rogin’s “Gogakushu,” it is written, “In Tokyo, there was a tradition called Ko-ido (old well) from long ago, but Soshio first called it Idowaki, and from then on it became well-known. The “Chakki Meiri Honsho” says, “Gowatari is called Idowaki,” but it is not clear how much later than Oido and Koido, or whether they were made around the same time, or even abbreviated.

The workmanship is generally a little thinner than that of wells, and the plateaus are not as free and unrestrained as those of wells. The glaze is a transparent soft white glaze with a slight bluish or yellowish tinge, and does not have the mixed and deep taste of wells. The shape of most of these bowls is flat and shallow, and the height is low like that of koido, but most of them are slightly larger than koido. There are rather few with wheel-thrown body, and even if there are, there are thick and strong penetrations like in Ido, and like in Ido, all the tea bowls have them, the thick part of the glaze is rough and the thin part is fine.

In addition, wells do not have circular hollows or circular engraved lines on the inner surface, which are called mirrors, but there are some with circular engraved lines on the sides of the wells. In terms of the number of wells, there are only five, but some wells have four or, rarely, three well sides.

Where were well sides created? This is also an open question. I have heard a theory that well-side was also produced in Jinju, Gyeongsangnam-do (South Gyeongsang Province), and pieces of well-side style pottery have been excavated from kiln sites in Goryeongsangbuk-do and Mureung, but the exact place of production is still unclear.

Idowaki is a fairly common relic, but the most famous Idowaki bowl is Nagasaki, which was passed down to the Hirase family in Osaka. It was owned by Nagasaki Shosai, a doctor in Kyoto. Shosai was a fastidious man and never owned anything with flaws, but this is the only one that he loved, calling it “Hakusho-ki,” meaning “Eight Victory Knots,” because of the way its cracks resemble the scenery. A similar piece with no cracks was owned by MASUKUDUDA BUNO, and I saw it just after the war, but it is not known where it has gone.

Soba

Soba is also known as soba well or soba kasu, and there are three theories as to the origin of this name. There are three theories as to the origin of the name: “Soba” is a misnomer, and “side” is better. The “Gogakushu” says, “Soba originally meant the side of a well, so it should be written ‘side,’ but nowadays we use ‘buckwheat noodle'” and Yusaku Imaizumi also says, “The original meaning is the side of a well – that is, side or beside – and not a well. In contrast to this theory, the “Meri-so” has a theory that the tea bowls and tea containers of the Koryo and Seto periods are not wells. In contrast, the “Meiri-so” says, “Soba-kasu is a common name for buckwheat dregs, and there is something like buckwheat dregs in medicine, hence the name. The name “soba” does not mean “buckwheat noodle” as it is often used. There is no established theory as to which of these two is correct. Soba, like Aoido and Idowaki, is not an old name, but was probably given to the area after the mid-Edo period.

At first glance, zoba looks similar to aoido, but it is not as massive as wellaido. It is made of rough clay with a slight iron content and is characterized by the presence of white quartz grains. The slimy glaze is similar to that of Ido and Aoido, but the glaze is a little lighter than that of Aoido because the glaze is a little thinner and the iron content of the clay is higher than that of Ido but lower than that of Aoido. Normally, the color is a pale blue-gray, which is said to resemble that of soba (buckwheat noodles), but some have oxidized to a pale yellowish brown. As with wells, the bowls are also glazed on the base, but the inner surface and the base are usually glazed with five eyes, as in wells.

The shape of the bowls are often flat, and as stated in the Yamanzumi family book, “The shape of the bowl is different for those who are good with their hands, the edge is slightly raised and the height is tightened, and the yellow-red and shallow yellow stains are replaced with the top. The shape and workmanship are similar to that of flat tea bowls of kohiki, and the rakuri is thinner than that of ido, but a little thicker than that of kohiki. However, common sense suggests that it was made in Gyeongsangnam-do Province. The number of artifacts is not as large as that of the large well, but it is larger than that of the small well, and there must be at least as many as in the small well.

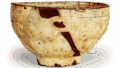

Rain Leak

Amereki refers to a teacup with light brown stains on a white ground as if rain had leaked in. There are two types of ameleki: those with a soft base and those with a hard base, similar to porcelain. The hard hand is called “Ameleki-kote,” and the hard hand is called “Ameleki-kote,” or “Ameleki-kote. There are also those made of coarse clay mixed with sand, which can be classified into several types. Ameleki is often mistaken for kohiki, and Imaizumi wrote, “Ameleki refers to tea bowls made of kohiki, which have a pale black stain on the glaze. As will be described later, Kohiki is made by applying white glaze to a blackish-brown base with iron, and then applying a transparent white glaze on top of the white glaze. While kohiki is delicate and elegant in its workmanship, ameleki is more boldly shaped and bold in its workmanship, and has a stronger base than ameleki. The white surface is characterized by light brown, light dark brown, and sometimes dark brown blotches, which, when examined closely, are the result of tea stains seeping in through cracks in the mountain, bubbles in the glaze surface, and vertical breaks in the rim, commonly called gutters.

Leaks were probably made in the same period as wells and well sides, but it is still unclear where and when they were made. The clay of Ameak varies and may have been made in several kilns, but it is reasonable to assume that the majority of Goryeo teacups were made in Gyeongsangnam-do or Jeollanam-do, and Ameak was probably made in Gyeongsangnam-do or Jeollanam-do. The Iwasaki family’s Ogurayama, which is listed in the Taisho Meikikan as a tamagote without distinguishing between amureki kote and kote, can also be considered amureki because it has a lemma on the body.

Kohiki, also called kofuki, is a type of clay with a high iron content that is completely covered with a white glaze inside and out, and then covered with a soft, transparent glaze. Hakeme is made by brushing white clay over a base of red clay, and the teacups commonly called plain hakeme have the entire inner surface covered with white clay, while the outer surface is covered with white clay up to the waist. The production is generally thin, and the rim is slightly traced on the edge, the height is low but comparatively large, and most of the bowls are shallow with a plump body.

The tea ceremony masters respect the unglazed part of the sliding door shape, which is commonly referred to as a hima. The glaze is applied by holding the boxwood bowl in the left hand and the ladle in the right, turning the bowl in a circular motion to pour the glaze over the entire surface. If the glaze is not applied to the entire surface of the bowl, the glaze is not applied, but the white makeup is applied to that area, and as the bowl is used, it becomes stained with tea stains and turns blackish brown, becoming one of the scenery of the bowl. Tea masters call this hima, and have loved teacups with hima since ancient times. The hima is usually in the shape of a sliding door from the upper right to the lower left, as when a tea bowl is held in the left hand and a ladle in the right, but in rare cases the hima is from the upper right to the lower left because the ladle is held in the left hand. The Miyoshi ware of the Mitsui family and the Kohiki ware of the Unshu Matsudaira family in the Hatakeyama Memorial Museum are examples of this type of ware. Some kohiki also have bubbles in the glaze surface, which have become leaks from the tea stains that seeped in during use. The Nomura family’s kohiki, which appears in “Taisho Meikikan”, is an example of this type of ware, with light black ameure on the inside and outside.

Hakeme was produced in the Namsun area, and some kiln sites of plain brushwork have been found in Jeollanam and Buk-do Provinces and Chungcheongnam-do Province, but it is believed that kohiki was produced in Jangheung in Jeollanam-do Province. It has been excavated only from the Jangheung, Boseong, Goheung, and Suncheon areas of South Jeolla Province, and it is believed that this is due to the abundance of white clay used for making white makeup in these areas.

A considerable number of mulled wineglasses have been excavated from the Boseong area in Jeollanam-do Province, and they have been found in Japan as well. There are also some types of powder-coated tea utensils that have been handed down from generation to generation, and tea ceremony masters respect the traditional types of powder-coated tea utensils.

It is not clear when kohiki was first produced, but most likely it was made in the early part of the Yi Dynasty, or the middle of the Muromachi period, around the 15th century, as was Mishima and Hakeme. Kohiki is thin and white, and many of its teacups have an elegant, dreary look.

Kote

Kote” is the word for “soft hand” or “gentle hand,” a name given because the base material is porcelain and hard and tightly fired. The word “kote” is used by tea masters because of its hardness, while today it would be called “porcelain.

Kote is further classified into kote honte, shirote, ameho kote, suna kote, enshu kote, gohon kote, e kote, hanshi kote, gozo kote, kinkai kote, kote mishima, etc., all names given after the middle of the Edo period. There are still many other types of katate that do not belong to these distinctions, and they are widely produced throughout the Joseon region.

Porcelain, or katte, has been produced in Korea since the Goryeo Dynasty, and by the time of the Yi Dynasty, there were many kilns in various regions of Korea. In the “Jirok of Yi Dynasty,” the geographical record of King Sejong lists a total of 136 places where porcelain was produced, including 14 in Gyeonggi-do, 23 in Chungcheong-do, 36 in Gyeongsang-do, 12 in Hwanghae-do, 31 in Jeolla-do, 4 in Gangwon-do, 21 in Pyongan-do, and 4 in Hamgyeong-do. The tea bowls called “Geode” and prized by tea masters since ancient times were probably made in Namcheon.

Some are white porcelain, while others have a slight iron content in the base, giving them a grayish color. Some are light yellowish brown in color due to oxidation, while others are painted with iron designs, and are called “eko-kate.

Tamagote

Tamagote is a tea bowl similar to Kumagawa, with a pale yellowish-brown skin that resembles the shell of an egg, which is probably why it was named tamagote. I have not seen any old tea ceremony records or old box notes. Imaizumi says, “In a word, tamagote can be described as an exquisite kohiki. The base material should be close to that of porcelain, and the texture should be similar to that of porcelain. The base material is close to porcelain, so some pieces have no nannin (penetration), and even if they do, the penetration is rough. The firing is usually oxidized and yellowish, but some are reduced and have a pale blue-gray color. It is strange to call them tamagote, but there are various classifications of tea bowls that cannot be determined by the current judgment.

It is still unclear where tamagote was made, but it was probably made in the Gyeongsangnamdo region. The shape of the bowl, which is similar to the Kumagawa style, with the edge slightly sloped, is considered to be a style unique to the mid-Yi Dynasty. This tea bowl is one of the relatively few surviving examples, and is not as well known to the general public as the Ido and Mishima bowls.