These were the most important and large-scale celadon kilns in the first half of Chinese ceramic history. As the name Yuezhou suggests, these kilns originated in the Yue region, centering on Shaoxing in Zhejiang Province, but as the period progressed, the kiln techniques spread to various regions in Jiangnan, and many Yuezhou celadon kilns emerged.

For example, there are kilns in Yuezhou, Wujiaoping, and Haridian in Hunan, Shihuwan in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, and Shobaba in Songxi County, Fujian Province. However, it would not be wrong to call them as such in a broad sense.

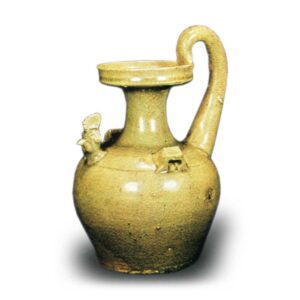

The origin of these kilns can be traced back to the end of the Later Han Dynasty or the Three Kingdoms Period. It is well known that ash-glazed ceramics with glaze mixed with ash feldspar were prevalent throughout China from the Warring States to the Han Dynasty, and the Yuezhou kilns emerged as a more modern production area following this trend. The Yuezhou kilns emerged as a more modern production area, probably due to the fact that the region was blessed with high-quality pottery clay and fuel, as well as convenient transportation via waterways. Vessels produced from the Three Kingdoms to the Western Jin Dynasty include various types of jars, flattened vases, bowls, and plates, as well as pavilions with a shrine and offerings built on top of the jars, lamps, incense burners, and figurines of tigers, lions, and sheep.

The clay is grayish-white and fine, and when fired, the ware is firm and solid. The glaze is a refined version of the Han Dynasty ash glaze, which has a more even blue-green color. Shells were often used for the eyes of the kiln to catch the wares, and red fire color often appeared around the white eye marks. From the Eastern Jin dynasty, celadon porcelain with iron spots, tenmoku glaze made of iron oxide and feldspar, and ame glaze appeared. In addition to Han-style vessels, new types such as Tianqi jars incorporating Western designs appeared.

From the Southern Dynasty to the Tang Dynasty, the Yuezhou kilns did not show any remarkable changes, perhaps due to the influence of celadon, white porcelain, and black porcelain from the north, but from around the end of the Tang Dynasty, they regained their initiative and were praised as the Yuezhou secret color kilns.

This was due to the success of producing a beautiful shallow green glaze color and the addition of silverware-style engraved and embossed designs on the surface of the wares, which added a new decorative effect. It was this late Tang dynasty (5th century) celadon of secret color that Lu Guemeng wrote in his poem, “Nine autumn winds and dew open the Yue kiln, and a thousand peaks of green come to steal away. However, with the beginning of the Northern Song dynasty (960-1279) and the rise of the northern kilns, as well as the emergence of full-scale celadon from the Longquan kilns in Zhejiang Province, Yuezhou celadon lost its vitality to these other kilns.