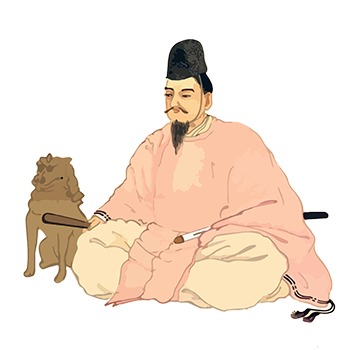

Kagemasa Kato Shirozaemon. Kagemasa is commonly known as the founder of Owari Seto pottery.

The name “Fujishiro” is an abbreviation of the upper and lower parts of his name. He shaved his hair in his later years and took the name Shunkei (or Shunkei). There are two theories about his biography. One is the famous one that has been handed down in Seto since olden times, and the other is the one found in “Bessho Kibei Issho Sho” written in 1595 (Bunroku 4). According to the former, Shirozaemon Kato was named Kagemasa, and his father was Motoyasu Fujiwara, son of Chisada Tachibana, who is said to have lived in Yamato Province (Nara Prefecture), and his mother was the daughter of Dofu Taira, who gave birth to Kagemasa in 1168 in a place in Yamashiro Province (Kyoto Prefecture). He always lamented the fact that his pottery was not as good as that of China, and had aspirations to go to China to study, but he never had the opportunity. In 1223 (Jouou 2), Dogen, son of Michicho, went to China. At the time, Zenji was 24 years old and Fujishiro was 56. After staying in China for six years, he returned to Japan in 1228 (Anjeong 2) at the age of 61. He made small jars from the clay he brought back there and presented one to the regent Hojo and another to Zen monk Dogen. He then went to his father in Matsuo, Bizen Province (Okayama Prefecture), or to his mother in Fukakusa, Yamashiro Province (Kyoto City), where he devoted himself to his mother’s welfare. He later heard that Owari Province (Aichi Prefecture) had been producing pottery since ancient times, and when he went to Seto Village (Seto City) in Yamada County, Aichi Prefecture, he found the soil in his grandmother’s bosom to be almost the same quality as that found in China. The remains of her house still exist today. To the north is the former site of Zencho-an. He died on March 19, 1249, at the age of 82. Another theory is that Fujishiro was a retainer of Minamoto no Yoritomo’s vassal, Katoji Kageren, whose family name was Chino and whose first name was Shirouzaemon. He was a skilled clay craftsman by nature, and always took pleasure in doing so while on duty. He had a son named Tatsuwakamaru, who loved birds so much that he kept him close during his studies. One day, Shirouzaemon ordered him to make water droplets in the shape of small birds, so he made sparrow droplets and baked them, which were much loved and praised. At that time, drinking powdered green tea after getting drunk was popular, and although not to the extent that many people held tea parties, there were many who used tea. However, the amount of tea cultivated was extremely small, so the shoguns sometimes gave tea to the lords in small quantities. In 1206 (Ken’ei era), during the reign of Shogun Sanetomo, tea was given to the feudal lords, and when they discussed what to use for the tea, they decided on ceramics. He was very pleased, and at first he made it at the Heiko Kiln in Owari Province. The largest jar was 9 cm high and the smallest was 4.5 cm high. This was due to the fact that tea varies slightly according to the qualifications of the lords. At this time, the tea was made in the shape of a sweet potato, which is now called “taro no ko” (sweet potato). As a reward for this, he was given a plot of land in a villa in Omi Province (Shiga Prefecture) with an area of 50 towns (5 hectares). His master, Kageren, was so pleased that he gave him his own family name and named him Shirozaemon Kato. The people called him “Fujishiro,” an abbreviation of “Fujishiro. From this point on, Fujishiro focused exclusively on pottery production and produced various types of pottery, but because he could not find the right glaze oil, he requested the Shogun to send him to China to learn pottery, and finally set sail for China in March 1212. In China, he looked at various types of clay and found that the clay from Jianzhou was the best, and no other clay was suitable. He lived with a potter and learned to mix glazes, and when he tried firing camellia and azalea ashes, he found that he could melt them to his satisfaction, so he made various forms of tea containers and presented them to the Shogun through Hojo Yasutoki after his return to Japan. This is the type of Chinese tea caddy prized by tea masters today. Originally, there were no tea containers in China, nor in Japan, but Fujishiro created them.

He died on January 17, 1234, at the age of 55.

His son Fujigoro inherited the remains. There are differences between the two theories. First, the periods are different. One says that he was born in 1168, and the other says that he was born in 1184, which means that the latter was 16 years later than the former. The inscription on the Tohso monument compiled by Hakko Abe in Shoen in 1866 (Keio 2) says that Fujishiro was 26 years old when he returned to Japan, which would place his birth in 1203 (Kennin 3), 20 years later than the second theory.

The first theory puts his age of departure at 56, the second at 29 since he set sail in 1212, and the third at 21 according to the Tōzō inscription. The first theory puts the year of his death at 82 in 1249, which is 16 years later than the second theory’s 1234. Although there are differences between the two theories, it is safe to assume that he lived from the beginning of the Kamakura period (Nian (116619) to Kencho (1249156). As for the purpose of his visit to China, it is said that he went to China to learn how to produce small vessels because the beauty of the mouth and high handles was not as good as that of Chinese small vases, or that he went to China to learn and pass on the use of underglaze blue, which was already available in China at that time. He was forced to learn how to make small jars, or karamono tea containers, and returned home. The tea ceremony masters distinguish between kuchibote, thick teapot, and dugout teapot made before his arrival in China, karamono (toshiro karamono) made after his return to China and fired with Chinese clay and glaze, kosedo (oseto for large and kosedo for small) made with Japanese glaze, and shunkei made after he had shaved his hair.

The above is a brief summary of Keisho’s history, but he was not born into a famous school at the time, and his influence after his success was not yet very great. His fame was due to the praise of the tea masters of later generations and the prosperity of his descendants. Even for his own works, his career history is known only rarely, and most of his works are based on guesses. In February 1824, he was enshrined in the precincts of Fukagawa Shrine, where he was called the god of tohiko. Tadashi’s descendants were divided into dozens of families in the ceramic production areas of Owari and Mino, and the Tadashi lineage in Seto is as follows: Tadashi’s son Togoro Masamoto was too ill to continue the family, and Fujisaburo Keikei (from his former wife) split off to Seto and took the name Asahi Junkei, which was his maternal family name, His younger brother Motomichi (Fujijiro, also known as Fujikuro or Fujigoro, later renamed Fujishiro) inherited the main family in the Bun’ei era (126475) and became the second generation of the family. He lived in Akazu (Akazu), and many of his works are of the Kiseto Haku-an style. His works are often of the Hakuan type of Kizeto, which is called Shin-Nakako and distinguished from Keisho’s Kozeto. Kagekuni III (Fujisaburo or Usashiro Tojiro, later renamed Fujishiro) inherited the main family in the Einin era (129319) and lived in Akatsu. His work follows the style of his great-grandfather Keisho. His name is known as “Kinkazan” or “Kinkazan” in Japanese. Masaren IV (Fujikuro, later Fujishiro, son of Keikuni) inherited the main family during the Kareki and Kenmu periods (1326-36) and is known today as Happugama. The name “Hafu” means “gable” in Japanese, because the glaze is applied to the gable shape of the roof, leaving the clay body in the shape of a gable. The following generations of artists are known to have inherited this kiln: Nobumasa V, Masamitsu VI, Motomi VII, Motobusa VIII, Kanemi IX, Motoharu X, Masanaga XI, Motoki XII, Keishun XIII, Keisho XIV, Harumune XV, Keimasa XVI, Haruhisa XVII, Harulin XVIII, Harukiyo XIX, Harumasa XX, Shunjo XX, Harusada XXI, Harufuku XXII, Haruhide XXIII, Haruyei XXIV, Tenryaku XXV, Shuraku XXVI, and Harujiro XXVII, Magojiro XXVII, and Taketaro XXVIII. In addition to Seto, “Wahari no Hana” and “Shinpen Seto Kiln Genealogy,” there are genealogies of the Akazu and Shinano kilns, as well as the Ohira, Sarutsume, Kusjiri, Oyasaya, Otomi, Kasahara, and Takada kilns in Mino Province. (Bessho Kibei Issho Sho, Chawaniki Bengokushu, Seto Pottery Abundant Roots, Shunkei Origin Book, Jangju Fushi, Kokin Meimono Ruiju, Owari Meisho Zue, Appendix of Pottery Reviews, Seto Pottery History Book, History of Seto Pottery, Japan Pottery History Essay, Journal of Dainippon Ceramic Society, 8, Japan Modern Ceramic Industry History, Wahari no Hana, and New Seto Pottery Lineage).