Insei, Kenzan, and Mokume are considered the three greatest potters in Japan. The family name of Kenzan was Ogata, and his first name was Yuyun, commonly known as Gonpei. The name Kenzan was given because the location of Narutaki (Ukyo-ku, Kyoto), where he built his first kiln, was in the direction of the imperial castle of Ch’ien. The name of Qianzan was derived from the fact that the location where he first built his kiln, Narutaki (Ukyo-ku, Kyoto), was in the direction of the Ch’ien of the Imperial Castle.

He was born in 1663 as the third son of Ogata Soken, a wealthy merchant in Kyoto. His family was descended from Hon’ami Koetsu, and his second brother was the famous painter Hohashi Korin.

In 1699, at the age of 37, he opened a kiln in Narutaki Izumidani, near Ninsei’s former residence, and began producing pottery. In 1712, at the age of 50, he moved to Nijo-dori Teramachi Nishi-iru Chojiya-cho (Nakagyo-ku), and his works from this period are called Nijo Kenzan. At that time, he was already favored by His Imperial Highness Prince Koukan, and when Prince Koukan moved to Kan-eiji Temple in Ueno, Edo, Kenzan followed him to Edo in the middle of the Kyoho period (1716-36), and lived in Iriya (Taito-ku) and baked various purification wares.

In the middle of the Kyoho period (1716-36), he went to Edo and lived in Iriya (Taito-ku, Taito-ku), where he fired various purification wares. His work is called Iriya Kenzan. In 1737, he went to Sano in Shimono-kuni (Sano City, Tochigi Prefecture) to make pottery. In 1738, Prince Koukan passed away, and five years later, on June 2, 1743, Kenzan died at the age of 81. In his resignation, he wrote, “I have been so miserable for 81 years, that I have never been able to forget a single word of my life. The happy times and the sad times are all a dream in the end. In accordance with the court’s wishes, he was buried at Yakuozan Zenyoji Temple in Shimotsuya-Sakamoto. However, the tombstone was moved to Kan-eiji Temple in Ueno at the end of the Meiji period (1868-1912), and was recently returned to its family temple, Sugamo Zenyoji Temple.

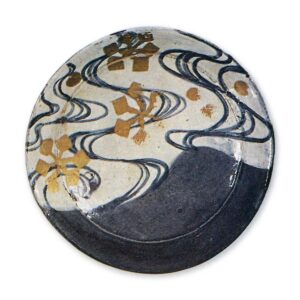

Since many of the vessels are low-fired, and are intermediate between pottery and earthenware, they are easy to forge, and since many master craftsmen of later generations copied them, it is difficult to obtain authentic works. The works of the third generation of Qianzan are often mistaken for genuine Qianzan works, but the paintings on them do not even come close to Qianzan’s work. The real strength of Qianzan’s work lies not in the quality of his ceramics, but in the way he painted his natural pictorial patterns as he intended to paint them. His works are rarely plain without painted decoration, and his style is unique in its high rhyme. He first studied the Dutch style, but after much painstaking effort in firing, he finally invented the Tang clay glaze, which is usually a white-brown glaze. The glaze is usually white-brown and soft, and the clay is reddish clay with small gravel. The glaze is usually white-brown in color and soft, and the clay is reddish clay with small gravels.

Although Qianzan was a disciple of Ninsei, his style was completely different from that of Ninsei, and many of his works have a Zen-like flavor and a simple elegance. The design and painting were of course influenced by Korin, but they also harmonized well with the vessels.

During the Narutaki period, many of his paintings were collaborations with Korin’s works. He was also a skilled calligrapher, and his calligraphy is said to have been handed down from the Koreans.

His disciple Ihachi Kenzan is known as the second generation Kenzan. During the Bunsei and Tempo periods (1818-44), a man named Wu Suke took the name of the third generation of Kenzan and produced pottery in the style of Kenzan. He also called himself Miyazaki Kenzan III. The manuscript in Kenzan’s own hand was handed down to Sakai Hoitsu, and then to Miura Kenya from Nishimura Kyakuan. The name of Miyazaki Kenzan was passed down from Nishimura Kyakuan to Miura Kenya, who used the name Kenya VI. In the Meiji era (1868-1912), Urano Kenya, a student of Kenya, was adopted by Ogata Keisuke and took the name Ogata Kenzan VI himself. In the Meiji period (1868-1912), Urano Kenya, a student of Kenya, was adopted by Ogata Keisuke and took the name Ogata Kenzan VI himself. It is said to have been composed by adding his own annotations to the biography of Insei. After his death, this book was handed down to Ihachi II, but later Kan Takatsuki found it in a certain gardener’s shop, and it became the property of Sakai Hoitsu. It was then in the possession of Nishimura Kyakuan of Utasendo around 1827, passed to Miura Kenya around Kaei (1848-54), and then to Otsuki Nyoden, before coming into the possession of Ikeda Nariakira.

It was later kept by Nyoden Otsuki, and then became the property of Nariakira Ikeda. The “Touki Mikuho Sho” was probably copied by him.