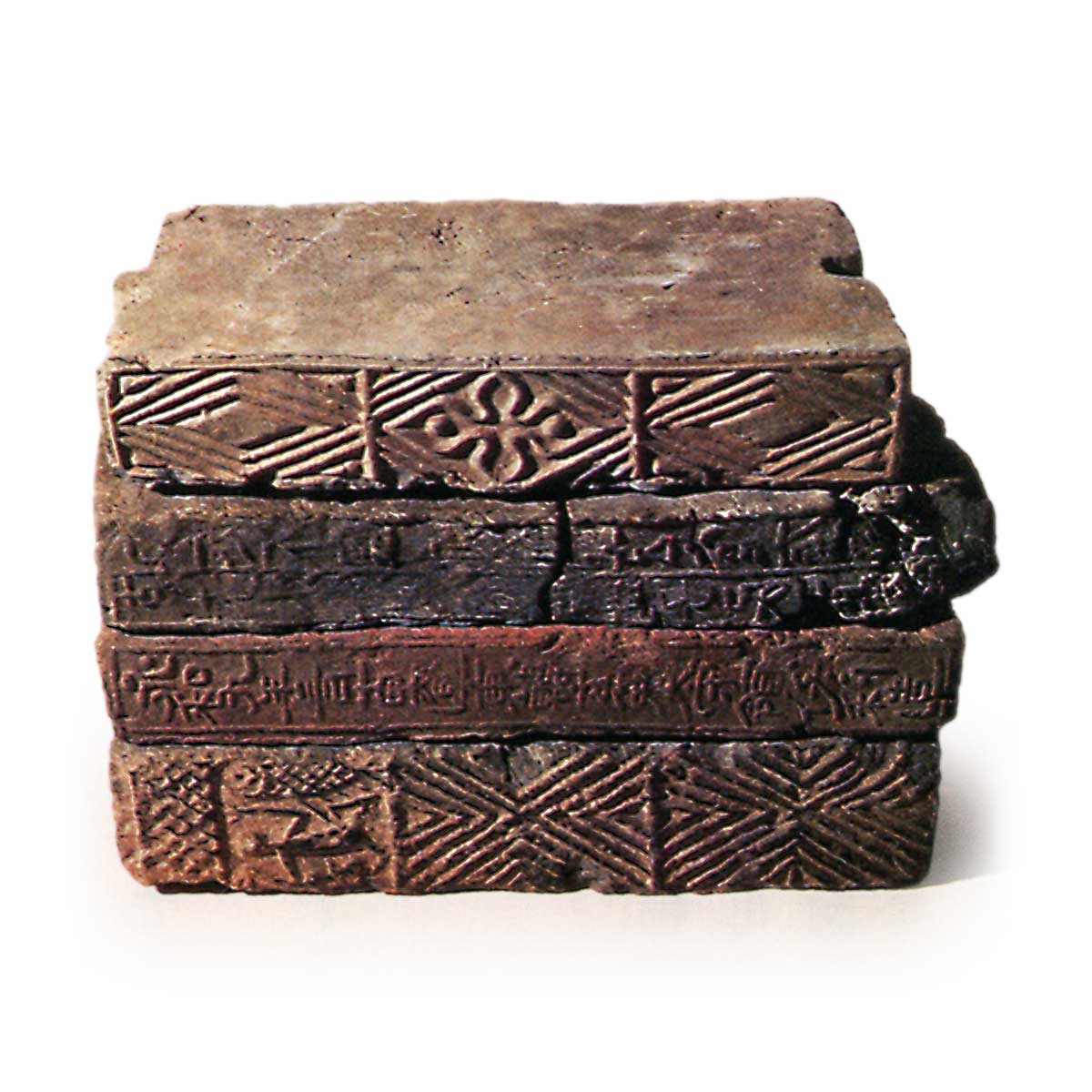

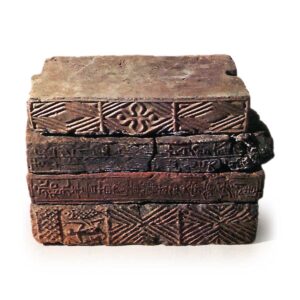

A building material made by molding and firing clay. Most are grayish-black and rectangular in shape, but there are also special shapes, such as wedge-shaped bricks for tubular ceilings, which are made in response to the position in which they are used. In other words, bricks developed in China. In modern China, it is also called shikigawara in our country. The same building materials used only after being dried after molding are called clay bricks or mud bricks, but in Japan today they are called sun-dried bricks in the European style. In Japan, however, they are called “sun-dried bricks” in the European style. Most of the sesamu are classified according to their shapes into three main categories: jiao sesamu, fang sesamu, and ku sesamu. The most common type, also called long anvil because of its rectangular shape, was used to build city walls, houses, towers, and tombs. It is usually around 30 cm on the long side, 15 cm on the short side, and 5 cm thick. The long side and the small side are decorated with inscriptions and characters, which not only provide information on the climate of the time, but also on the year, the person buried in the tomb or the builder, the maker of the vase, and auspicious phrases, making the vase an important source of information on the exact date of construction, the person buried, and other details. Square vessels are square in shape and are placed on the floor, around buildings, on roads, or affixed to walls. Unlike the jokan and fangban, kuukan, also called kuukashinban, is hollow, a characteristic that gives it its name. The shapes vary from rectangular to square, triangular, columnar, and roofed, and the sizes vary as well, with the largest reaching 130 to 140 cm in length. The front and back surfaces are decorated with pressed patterns in the form of yang or yin, and are densely decorated with figures, chariots, horses, cavalry, hunting scenes, birds, beasts, fish, trees, houses, coins, animal rings, and various geometric patterns. The sky is also called because each of these shapes was often used to assemble tomb chambers, but they were also used for palaces and other above-ground structures.

The production process of the veneer has not been studied in detail from the viewpoint of production techniques, so the following is an excerpt from Song Ou Xing’s “Tian Kou Kai Matter” from the Ming dynasty of China, which provides an overview of the production process. The soil was moistened with water, and an ox was made to tread on it with its feet to knead it. The clay is packed in a wooden frame and cut with an iron wire bow to make the base. The clay is placed in the kiln, and it takes one day and night to fire a hundred-pound (60-kilogram) piece. There are two types of kilns: wood-fired and coal-fired. When wood is used, the kiln is blue-black, and when coal is used, the kiln is white. The wood-fired kiln has three holes in the top and sides to let out the smoke, and when the fire is sufficiently hot to stop, the holes are tightly sealed with mud. The kiln is then rolled with water (see “Tile Kiln” section). If the fire is one vehicle short, the color of the rolled tiles will not be shiny. If three kilns are used, the color of the original clay remains in some places, and when exposed to frost or snow, it reverts back to the original color. If the amount of fire is too much for one kiln, cracks will form. If the amount of fire is too much for three kilns, the kiln will shrink, crack, and remain bent, making it unsuitable for use. To check the heat level, look through the hole in the kiln to see through the inner wall. The clay is subjected to the fire, and the shape of the potter’s wheel will move, as when gold and silver have been completely melted. It is the potter’s head’s job to discern this. In a coal kiln, the height is doubled compared to a wood-fired kiln, and the top is made smaller and smaller, leaving the top open without blocking it. A large tadon made of coal with a diameter of 1 shaku 5 sun (45 centimeters) is placed on top of a single tadon, followed by alternating stacks of bricks on top of the tadon, and then piles of reeds are piled on top to burn them. The empty tadong were used for a short period of time from the Warring States Period to the Han Dynasty, and their excavation sites are almost exclusively in the Zhongyuan region.

They were used to replace wood in traditional pit tombs since the Shang and Zhou dynasties. The climate of the Yellow River basin was dry and unsuitable for forest development, so Kuang’s invention was intended to compensate for the lack of wood. By the end of the Late Han Dynasty, the use of both hollow and braided tombs appeared, and in the Late Han Dynasty, the use of hollow tombs became rare and braided tombs were constructed exclusively with braided tombstones. The most common structure of a cinerary tomb is a vaulted ceiling, or a cylindrical ceiling made of wedge-shaped cinerary vessels arranged in an arched configuration.

The cairn tombs spread from Zhongyuan to all over China during the Later Han Dynasty, and further east to the Pingyang area, north to Inner Mongolia, and south to Indochina. Fangban have also been around since the Warring States period. As an example of its use in above-ground structures, at the site of the presumed foundation of the Royal City of Zhao, a jiangban and fangban were found buried vertically with the long side up, as if they were circling the outside of a row of foundation stones. On the front and back sides of this sarcoma, there is a rope pattern. Unlike the molding method described in “Tengo-kaimono,” this method involved pounding clay into a wooden frame from both sides, using a kind of beating mold with a rope wrapped around it, or a medium of some kind. In the Han Dynasty, there are known to be traces of buildings with walkways and floor surfaces made of fangban. These fangcun were covered with geometric patterns such as lightning and small bumps to prevent slipping. The fangs found in cliff tombs of the Later Han Dynasty in Sichuan Province include religious figures such as Xiwangmu, production activities such as harvesting, and figures of chariots, horses, banquets, and guests, providing valuable clues to the reality of life at that time. In the Later Han Dynasty, the method of constructing a tomb by layering the floor of a chamber tomb with an amidai structure and the walls with alternating longitudinal flat piles and small vertical piles gradually became common, and was carried over to the Three Kingdoms and the Northern and Southern Dynasties periods. The famous tombs of Baekje and the tombs of Songsan-ri in Gongju, Joseon, belong to the lineage of this construction method. Although tanshitsu tombs continued to be built after the Tang Dynasty, they no longer have painted inscriptions on the walls. The Qingling Tomb at Wahluin Manhua in Inner Mongolia is another example of this type of chamber tomb. The Abuyama burial mound in Nasahara, Takatsuki City, Osaka Prefecture, is a tomb chamber made of granite and sarcophagi, with the interior finished with plaster. The was used both on the makashiwa platform and on the ceiling of the stone chamber. The stone is blue-gray in color, hard, and bears concentric circles on one side. A small stone vase found in a Goguryeo stone mound in Ni’an County, Jilin Province, China, has “Gantai Wangling An Ruoshan” and “Thousand Autumns, Ten Thousand Years, Eternal Firmament,” which clearly indicate that it was made under the influence of Han culture, but this vase was not used to build a tomb chamber. The correct usage is not known, but it was used to roof the top of the stone mound with tiles. As Buddhism spread in China, multi-storied pagodas were built with tiles, following the Indian practice.

The 12-cornered, 15-storied pagoda of the Takakku Temple in Tengfeng County, Henan Province, built in the mid-6th century, and the large goose pagoda of the Ci En Temple and the small goose pagoda of the Fu Temple in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, built in the early 8th century, are well known examples of this practice. The five-story pagoda at Songnimsa Temple in Chilgok-gun, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Korea, which became famous when it was discovered in 1959 with the Buddha’s stupa still buried, is estimated to have been built in the late 7th century, either at the end of the Three States Triple Triangle Period or at the beginning of the Unification of Silla. This pagoda and the pagoda at Sinryeoksa Temple in Yeoju-gun, Gyeonggi-do Province, are also in the Chinese traditional style. In Japan, most pagodas are made of wood, and only a few stone pagodas are known to have been built. The influence of Buddhism appeared in various areas after the Nanbokucho period (1392-1644), and the pictorial design of the pagodas was no exception. During the Nanbokucho period, in addition to traditional designs, other designs such as , lotus flower, and arabesque designs were also used. During this period, glazed wares were also produced, thus laying the groundwork for the culture of the Tang dynasty, which was characterized by variety in terms of both design and color. During the Tang dynasty, the traditional designs and textual expression that had been used since the Han dynasty almost completely disappeared from the glazed vessels, which were decorated mainly with designs that had been introduced by Buddhism. The countries of East Asia then imitated the Tang style. A tungban found in Tokyo City of Balhae, which flourished in the northeastern part of China, has a rope pattern on the reverse side of the baosanghua design, indicating that a beaten pattern with a rope wrapped around it was still in use. The six types of painted wares found at the temple site in Ihamyeon, Buyeo, Chungcheongnam-do, Korea, are also well known, and the hosanghwa patterns and green-glazed wares found in wares from the Unification Period of Silla are particularly splendid. In Japan, a particularly famous example is the Panglong ware excavated from Oka-ji Temple, Koichi County, Nara Prefecture, that depicts a celestial being and a phoenix respectively, which is thought to have been fitted into a hip wall or pedestal. Other vessels with flying cloud and floral motifs, as well as green glazed vessels with water wave motifs, have also been found at temple and palace sites dating from the 7th and 8th centuries. Untextured were rather frequently used in the construction of temples and palaces. Bones have also been excavated at Fujiwara Palace, Nagaoka Palace, and Kofukuji Temple, and recent excavations at the Heijo Palace site have revealed the remains of a building with a base built up of noodles piled around it.