A small ceramic jar used to hold powdered tea. Since the tea ceremony became popular, it has been widely respected as a traditional treasure with names such as “Daimyo-mono” and “Chukyo-mono”. These small vases range in size from 3 to 13 or 14 centimeters in height and 8 to 27 centimeters in circumference. The lid is made of ivory (old ones were made of deer horn), and the lid is wrapped in a bag made of gold brocade or other fabrics.

The tea container was introduced to Japan with the development of the tea ceremony in Japan.

The name “matcha tsubo” was not used by tea masters at that time, and it was not until the Azuchi-Momoyama period that the term “chayu” (tea container) appeared. Originally, all tea containers were of Chinese origin and came from China. However, these vessels were not originally made in China as tea containers, but were actually made as miscellaneous vessels such as medicine jars, condiment jars, condiment containers, and hair oil containers. There is no proof of its origin in China, but there are various theories that it was made in the Ding, Guangdong, or Jizhou kilns. The date of the first arrival of tea caddies in Japan is, of course, uncertain, but legend has it that in 1191, when Zen master Eisai returned from the Song dynasty in China, he brought with him for the first time a Chinese tea caddy called kogaki chaju along with tea seeds. It is also said that Dogen Zenji brought back the Daimyo no Kuga Hashirazu when he returned from the Song dynasty in 1227.

Even if we were to believe these legends, it is difficult to believe that the tea utensils were used as tea utensils at a time when the tea ceremony had not yet been established. They were probably brought as yaku-iris or curious small vases. Since the rise of tea ceremonies in the Higashiyama period, the circumstances surrounding the importation of tea containers have gradually become clear, and since Chinese tea containers were sold at a surprisingly high price at that time, merchants and boatmen who sailed from China to Sakai, Nagasaki, and Hakata actively collected and imported these Chinese vessels to Japan. There are many stories that the adventurous Japanese merchants of the time, the Luzonese, who were after Japanese pirates, often raided junks bound for Lu-Song, Sumatra, and Taiwan in order to plunder these most lucrative ointment jars and condensed medicine containers. The production of tea caddies in Japan, based on these Chinese tea caddies, began in the late Muromachi period (1333-1573), the period of the rise of the tea ceremony, and Seto was the center of the tea ceremony. It is clear that the founder of Seto pottery, Fujishiro Kagesho, who is also said to be the originator of tea caddies, could not have been a person from the Kamakura period as legend has it.

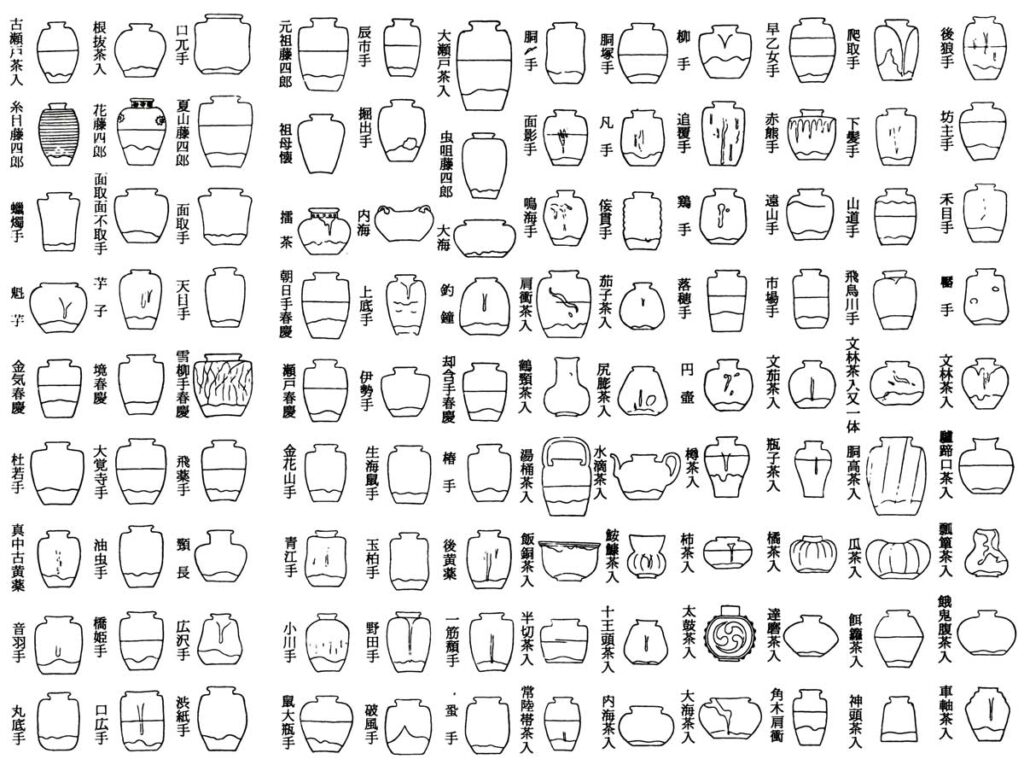

Charyu are divided into two categories: imported (Karamono) and domestic (Wamono), and Wamono are further classified into six kiln divisions: Heiko (Koseido and Shunkei), Manchuko, Kinkasan, Happugama, Gogama, and Kokuniyaki. These six categories are: Heshiko-gama (Kose-do, Shunkei), Shinchuko-gama, Konkasan, Hafu-gama, Go-gama, and Koku-yaki. (1) Tang ware: Tea containers introduced to Japan between the Song and Ming dynasties of China, and all tea containers made in Japan in later periods are rooted in this type of ware. To distinguish them from the works of Fujishiro, which are called karamono or Fujishiro karamono, we refer to this type of genuine karamono as hanzaku karamono.

(2) Tea caddy made by the original Fujishiro at the Heiko Kiln (Koseto).

(2) Koseto: Tea caddies made by Fujishiro, who was the original master of the Heiko kiln. The term “Koseto” refers to the second generation Shin-Nakako, and the third and fourth generation Koseto, and is the general name of the original Fujishiro’s work. The works include thick-stemmed, kuchibote, nen-nuki, oseto, koseto, meimono te, sembe te, hidate te, hagatte, imoko, suricha, mimotsuke, round jar, bunrin, eggplant, shirikomi, naihai, oumi, tebin, dashunkei, shunkei gourd, shunkei mouth gourd, shunkei tobiyo, shunkei ten-o-mouth, shunkei rice barrel, and others. (3) Made by Fujishiro Manakako 2nd generation, they include Hashihime te, Noda te, Obe te, Ogawa te, Shigawa te, Mentori te, Mentori mentsuri, Imo no ko, Daikakuji te, Yanagi Fujishiro, Itome Fujishiro, Hana Fujishiro, Grandmother bosom, Duwaka te, Soko mentsuri, Ue, Shunkei rice vat, Shunkei candlestick, Koyaku te, Kikyaku te, Shunkei rice vat, etc. There are also candlestick, yellow medicine hand, yellow medicine hand, back yellow medicine hand, high body, bamboo ears, half cut, rice barrel, ocean, eggplant, savings, big mouth, water drop, and so on. In addition, Prefectural Shunkei, Tsurutou, Suricha, Yukishita Shunkei, Iro Shunkei, Natsuyama Shunkei, Te Shunkei, and Seto Shunkei, which belong to the Fujishiro Shunkei group, are also believed to have been made in the Manchu Kogama kiln. (iv) Kinkasan (secondhand): made by Tojiro III, these include Gokuno Te, Kubinaga Te, Asukagawa Te, Tamakashi Te, Takinami Te, Ikkaisu Te, Hirosawa Te, Ban’yono Te, Shinnyodo Te, Tenmoku Te, Aburamushi Te, and Oikou Te. (v) Hafu-gama (secondhand): This kiln was made by Fujisaburo IV, and includes Ote, Ichibaite, Kuchihirote, Shibugamiite, Suribokiite, Ikuretoriite, Saotomeite, Otowaite, Bonte, Tamagawaite, Yoneichiite, Dotte, Dotsukaite, and others. Shoshin shunkei, Sakai shunkei, Kiya shunkei, Yoshino shunkei, Kinki-shunkei, and Isete shunkei, which belong to the Later Period shunkei, are said to be from the Happugama period. The Manchu, Kinkazan, and Happu kilns are collectively referred to as the Seto main kiln (as opposed to the Keiko, Gogama, and Kuniyaki kilns). (The tea containers made by Seto or Kyo Seto potters of the Rikyu, Oribe, and Enshu periods are called “Go Kiln”. The following types of tea containers were made by such potters: Sohaku, Masayi, Shozan, Genjuro, Chausuya, Man’emon, Takean, Shinbei, Ezun, Tokuan, Kichibei, and Moemon, etc. Also, Boshute, Rikyu, Rikyu Market, Oribe, Narumi, Anete, Yatsuhashi, Nenkan Te, Dimple Te, Yamamichi Te and Shimoge Te belong to the Later Kiln.

(7) Tea containers made in kilns other than Kuniyaki Seto, including Satsuma, Takatori, Zessho, Tanba, Karatsu, Bizen, Iga, Shigaraki, Omuro, Ueno, Ujitawara, Kutani, Shidoro, and Yatsushiro. In addition, there are island (Annan, Ro-Sung, and Joseon) tea caddies.

In the “Seto Pottery Source,” it is written, “Tea utensils have been called ‘masterpieces’ ever since the Ashikaga Shogun Yoshimasa established the ceremonial rules of the tea ceremony. The tea caddies, jars, vases, tenmoku, doudai, tea trays, ladles, and water jugs are called “masterpieces”. The respect for ink brush strokes began with Master Shukoh. It is truly a national treasure, but it is also a family’s national treasure. The tea ceremony of Sukiyodo became very popular under the reign of Nobunaga Hideyoshi, and Rikyu devised the Wabi-style tea ceremony, which is still practiced today. (Note: In later times, these vessels were called “meimono,” and later, “daimyo meimono.) (Note: In later times, these vessels were called “meimono,” and later, “great meimono.”) During the reign of the third Tokugawa shogun, Kobori Toe-mori Masakazu, who was skilled in the art of sukiyori, selected tea utensils and made them famous, including secondhand and kokuni-ware, and called them Enshu meimono (or chukkyo meimono), It is also called Honka. These are the treasures of the family, but not the treasures of the world. In those days, the students of Seiichi selected items that had been left behind and called them “Dote Meibutsu” (famous items). In other words, the items that were valued during the Higashiyama period and the reigns of Nobunaga and Hideyoshi are called “Daimyo-mono. They are all Chinese-style kara-mono and koseto (Fujishiro kara-mono). Later, Enshu Kobori selected and named the best pieces, from Fujishiro to Kuniyaki, and called them Chukko Meimono (see “Meimono” section). (See the section on “Meimono.” Most of the existing Meimono tea caddies are listed in “Taisho Meikikan”). The first of these are eggplant, bunrin, shirikomi, round jar, jiaozu, daikai, imoko, wheel mouth, ten-o’s mouth, hanabekuchi, persimmon, bottles, rice cave, monkfish, water drop, teb bottle, vine, body height, ear, crane neck, barrel, melon, feeder, gourd, yuboko, daruma, bun nasu, hankiri, chakushiki, citrus, kanjiki, and a variety of other types of tea containers. The various types of tea containers, classified according to their shape, were inscribed with a poem, which refers to the shape, whereabouts, or origin of the container. The tea ceremony vases were inscribed with ancient poems in addition to a wide range of other factors such as shape, scenery, and origin. In short, the inscriptions of the great master tea masters were relatively simple, but after Kobori Enshu used the song inscription (after the Chuko Meimono), the inscriptions of tea containers became much more complicated. The word “hon-uta” is derived from the poetry school term “hon-uta-tori,” and refers to the first inscription of the same type that Enshu Kobori inscribed when he inscribed a tea container. In other words, if Enshu inscribed Asukagawa on a particular tea container based on an ancient poem in the Kokinshu, “Asuka River flows through Asuka River and it is early in the moonlight,” Asuka River is, in fact, the main poem, and later, on another tea container of the same type as Asukagawa, he inscribed “I do not know, but my boundless heart is known,” from the Go-senju, “The Poet’s Anthology of Poetry. The Asuigawa is, in fact, the original poem, and if it is inscribed “Kumoi” from “I don’t know, but my boundless heart is unknown to those who live far away,” then this Kumoi would be called an Asuigawa teamei (tea caddy). The “chairi no kama-bun” is a classification method that first classifies various types of chairi under the hand of the poem and then determines the type of kiln to which the particular type of chairi belongs.

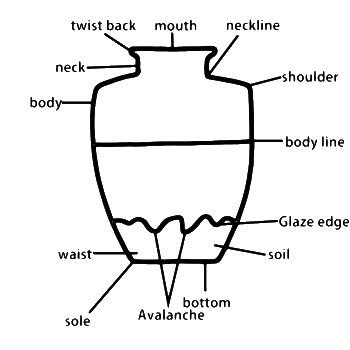

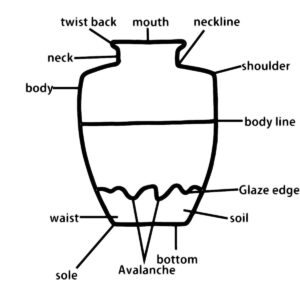

The five main points of interest are as follows. (The tea utensils that have been called masterpieces since ancient times always have these five points of interest, and the best tea utensils are those that have these five points of interest in equal order. First of all, the mouth should be soft, yet vigorous and well-rounded, and the twist back of the mouth should be smooth. There are three types of twists: round gauze, flat gauze (ipponji), and kuchi-string. The area between the mouth and the shoulder, which is called the steamer, is also a highlight and must be well balanced with the twist back. The shoulder is the most important point that determines the beauty of the shape of the tea container, and there are different types of shoulders such as Shunkei shoulder, Nade shoulder, Maru shoulder, and Dan shoulder, depending on the type of tea container. There are also different terms for the body, such as “body height” and “body tension,” depending on its construction. The waist belt, which goes around the middle of the body, is also important because it tightens the overall appearance of the tea container. The waist is the part of the body that gradually curves from the shoulder to the body and then to the waist, finally reaching the bottom, and is also where the edge of the glaze is located. Itokiri is the cutout on the bottom, also called tatami-zuke or bon-zuke, and the way the bottom sits when the tea container is placed on the table is also an important condition to look at. It is an old theory that the left-handed thread cutting is for Karamono and the right-handed thread cutting is for Wamono, but it is difficult to determine the difference. There are also names such as “whorl itokiri” and “maru itokiri. Other types are called “yakushi” or “ita yakushi” and have a solid bottom, which is considered to be of lower grade. (2) The life of a glazed tea caddy lies in its shape and glaze. There are three types of glaze: base glaze, overglaze glaze, and weeping glaze, which are referred to as “scenery” in terms of appreciation. Imaizumi Yusaku’s theory on glaze is summarized as follows. Shunkei glazes consist of a single glaze color with a water glaze sprayed on top. Asahi Shunkei looks as if the morning sun is reflected in the eastern clouds. Seto glaze generally consists of a brown base glaze with black overglaze, and nadare is also available in black and yellow. The yellow glaze is said to have been produced by Fujishiro II. A glaze break is when a small amount of the base glaze remains under the overglaze. Quail spots are black spots that remain under the overglaze. In nadare, tasuki nadare refers to a net-like scene. An example of this is the famous Yukiyanagi Shunkei. Glaze change refers to a change in the color of the nadare due to the heat of the fire. There are gable, mountain road, and Ichimonji in the glaze edge. A gable has a gable-shaped glaze edge, a mountain path is a curved line with a difference in height, and an ipponji is a straight line without a difference in height. Hi-changen means that the ground glaze has changed because of the katsuki angle of the shoulder attachment. Kata-megawari refers to a change of color in the front and back halves of the body. Ura-glaze” refers to a glaze change on the back of the tea caddy. There is also a type of tea container called oki kata. The oki kata refers to the front of the tea container, which is the most important part of the tea container or the part of the tea container with the most important scenery. The following are some of the books written on the kiln portion of chayu and chayu in general: “Bessho Kibei Ichiko Sodensho,” Hoshuuan “Seto Kiln Portion,” Ichigenan “Chayu no Shinbun,” Seto Toki Banroku, “Chakki Bengokushu,” Manpo Zensho, 6 and 7, Chayu Hourin,” Sanbutsu Meimonoki,” Chayu Meri-no-sho,” Kokin Meimono Ruiju,” Chakke Drunken Olden,” Honcho Novelogue of Ceramics, A View of Tea Bowls, Koryo Tea Bowls and Seto Tea Bowls.