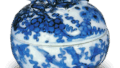

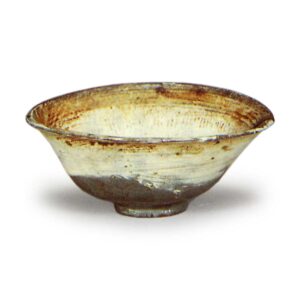

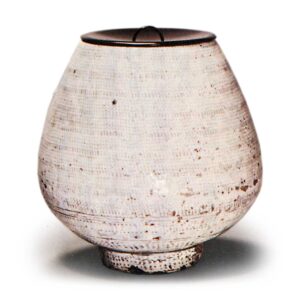

Mishima is a group of pottery produced in Korea. The origin of the name is commonly attributed to a pattern on the Mishima called “Ryoyote,” which is a mixture of dotted line and dense floral patterns similar to the appearance of calendars distributed by the Mishima Taisha Shrine (Shizuoka Prefecture) in the past. Tauchi Baiken says that the three islands of Amagang (Macau), Lu-Song (Philippines), and Taiwan are collectively referred to as Mishima, but this is a bit of a stretch. According to Asakawa Hakkyō’s theory, Geomundo Island has been called Mishima in Korea since ancient times, and because of the tidal currents, Chinese and Japanese vessels gathered on this island to trade pottery produced in the area. The name Mishima, however, was given by Japanese tea masters, who, as is commonly believed, probably took the name from the pattern of the tea bowls. In “Rikyu Hyakkai-ki” and “Nanto Matsuya Chakkai-ki,” the name Mishima is found from around 1586 (Tensho 14). At that time, the Wabicha trend was in its infancy, and the traditional Chinese tenmoku tea bowls for tea for nobles were being replaced by Korai tea bowls, and Mishima’s modest splendor and Wabi-style elegance were finally being appreciated. There are three types of patterns similar to Mishima calendars: one with a small bead pattern engraved and filled with white mud, another with a simplified version engraved vertically with spiral lines and filled with white mud, and another with lines engraved radially from the prospect like a rope curtain and filled with white mud. All three types are found in the hand.

All three types are thought to be variations of Goryeo celadon inlaid hands. The name “mishima” has now been expanded to include all ceramics other than white porcelain produced in the late Goryeo Dynasty and early Yi Dynasty.

The name “mishima” has been used by tea masters and antique dealers since ancient times to refer to various types of ceramics. From the perspective of technique, there are carved mishima, nail carved mishima, brushed mishima, painted mishima, and so on.

From the decorative side, there are Hana Mishima, Higaki Mishima, Reibin Mishima, Kaku Mishima, Whirlpool Mishima, and so on. Names according to period include Kowatari Mishima, Chosun Mishima, and Tenshodo Mishima. The names of the islands include Gohon Mishima, Hanshi Mishima, Katate Mishima, Iraho Mishima, Kuro Mishima, and Omota Mishima, based on the color and mottled pattern of the soil. Other names include Ina Mishima, Kone Mishima, and Misaku Mishima (see respective sections). In terms of production techniques, they can be divided into the following three categories (1) Inga-ware with an inlaid flower pattern stamped on the surface, covered with a decorative coating and then wiped off to give the appearance of inlaying, and then glazed. Some of the patterns are carved in the sealed flower pattern. (2) Brush-worked clay that has been brushed on and left without being wiped off. The majority of the decoration is brushwork, although some inka is mixed in. (3) Carved Mishima: A piece that has been carved on top of the carved Mishima clay to reveal the underlying clay.

The most common type of mishima pattern is the vertical nani-mata, which consists of numerous vertically stamped nani-mata marks approximately three centimeters in length. The next most common patterns are the vertical naniwa-kei tsunagi and wan-tsunagi, which are probably a variation of the flying cloud pattern of the Koryo cloud cranes. Next, small chrysanthemum marks were stamped as komon scattering. The next is a small chrysanthemum pattern with a small chrysanthemum mark, followed by a four-eyed pattern like ganmoku and Takeda-hishi, a heart-shaped boar’s-eye pattern, and a sword-tip pattern. In addition, dragon and phoenix, lotus flower arabesques, and nani shapes are freely used in carved Mishima. However, patterns of human figures and animals are rarely seen. In 1927, the Korean Governor-General’s Office conducted an excavation and survey of the Choryongsan kiln in Gongju County, Chungcheongnam-do Province, and found that the kiln produced almanacs, brushed Mishima, painted Mishima, and other wares. According to the Geographical Survey of King Sejong in the “True Records of the Yi Dynasty,” the Joryongsan kiln was a porcelain manufactory, and its products were considered to be of medium quality. In other words, Mishima was called Sejong-era porcelain, and the Mishima of Choryongsan was a middle-grade product at that time. According to the Geographical Survey of Japan, there are a total of 136 porcelain factories in eight provinces where Mishima porcelain was made. Of these, only the kiln site at the foot of Jiryong Mountain has been academically excavated and reported, so further research and investigation is warranted. Of these 136 porcelain sites, the finest and most refined products were found in Gwangju in Gyeonggi Province, Goryeong in Gyeongsangbuk-do Province, and Sangju in Sangju Province, leaving a total of only four sites.

The most characteristic feature of Mishima ware is that many of the plates and dishes are marked with the name of the local government. This was ordered by the government, but it was also treated as a part of the design and used for decoration, making it unique. According to the “Yi Choso Jitsuroku” (The True Record of the Yi Dynasty), since the damage caused by the private collection of official objects became more and more serious year by year, in the 17th year of King Taejong (1417~24th year of Oeong), the government had the koso inscribe their names with the approval of the koso. Therefore, even though there are some exceptions, as a general rule, those inscribed with the title of “Shigane” can be considered to have been made in the 17th year of King Taejong or later. After Mishima-te production ceased, dishes inscribed with the title of “司号” were rarely seen. There are three main methods of inscribing characters on Mishima. (1) Those inlaid with white clay to show the inscriptions. Black clay inlays are extremely rare. (2) Iron-glazed vessels with characters written on them. (3) Those inlaid with characters on the bottom of the vessel. The characters on Mishima inscriptions can be divided into three main categories: names of officials, names of people, and others. (1) Those with the name of a government official. (2) Those with the name of a government official: Naishomemji or Uchichom for short. (2) Those with the name of a government official. (2) The name of the official. Reibin-ji Temple or two characters for “reibin,” or four characters for “reibin temple. Some Jangheungsa are named after places, such as Gyeongju, Gyeongsan, Milyang, Changwon, Ulsan, Yesan, Haesu, Jinju, Eonyang, Seongju, and Yangsan. These are known to have been made at porcelain makers in those areas, and are reliable specimens of local porcelains. In Inju-fu, there are rare examples bearing the names of places such as Goryeong and Eonyang. In addition to the above, some are inscribed with a single character, such as “Shi,” “Nai,” “In,” “Chang,” “Dai,” and so on. All of them seem to be abbreviations of government offices. (2) Names with personal inscriptions. In the third year of the reign of King Sejong (1421 – 28 Oei), the chief engineer of the Ministry of Industry and Commerce was appointed to write the name of the artisan responsible for the work on the bottom of the dish to be presented to him. Today, the name of the master craftsman is rarely found inscribed on the bottom of the dish, but it can often be seen written in black ink. (3) In addition, there are also characters for “供字”, “戒”, “果”, “河河”, “三陟”, “殷皿”, “山”, “星州”, and so on. Some of the characters on Mishima inlays are extremely difficult to read. Some of the characters have broken strokes, some are abbreviated, some are misspelled, and some are reversed. The typefaces used include gradations, lines, and clerical scripts, and some of the characters are almost entirely drawn. Some of the characters are surrounded by circles or straight lines, while others are not. The position of the letters differs from dish to dish, but the technique is elaborate according to the number of letters and the tone of the Mishima design, and the engraved letters have become a part of the design.

Mishima imitations in Japan] Many Japanese potters made Mishima handles at the Busan and Taizhou kilns, and they have also been made in Kyushu for a long time in Yatsushiro, Gengawa, Satsuma, and other areas. Mishima imitations can also be found in Hagi, Izumo, and Seto. In Kyoto during the Bunka-Bunsei period (1804-1303), many potters, including Niami Michihachi, made Mishima-te.