The works of Kōhō Sōsa, who is thought to have had a great influence on Kenzan, are not as well known as those of Ninshō and Kenzan, but they are highly regarded in the world of tea as works that demonstrate a unique style of Kyoto-yaki pottery. For this reason, in this volume we have also selected and illustrated some of the works that predate Kenzan ware, and so, before giving an overview of Kenzan ware, we have decided to give a brief description of Kūchū ware here as well.

Kōsai Kōhō was the grandson of Hon’ami Kōetsu, and was born in 1601. He died in 1682 at the age of 82. By the time of Koetsu’s death in 1637, he was already 37 years old, so he had a thorough knowledge of Koetsu’s life in his later years after he took up residence in the hermitage at Takamine. It is thought that the influence of Koetsu, who had a well-rounded personality and the air of a master, was great, and it is also thought that his desire to make Raku tea bowls and Shigaraki-style pottery was due to his admiration for Koetsu.

He also lived a long life, from 1601 to 1672, so he was someone who knew the full story of Kyoto-yaki from its beginnings to its completion, and he was friends with Horin Shōshō of Rokuon-ji, who left important records about Kyoto-yaki , and of course he was related to Kinkin-ya, the birthplace of Korin and Kenzan, and it is said that he taught Ogata Gonpei (later Kenzan) the Raku ware pottery techniques of Koetsu, but Gonpei was only 20 years old when Koetsu died.

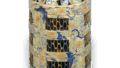

It seems that Kuchu-sai’s pottery was not part of the family business, as was the case with Koetsu, but judging from the works that have survived, his range was wider than Koetsu’s, and he was known for making not only Raku tea bowls but also works in the style of Shigaraki ware, to the extent that he was called “Kuchu Shigaraki”. However, it is thought that the Kuchu Shigaraki ware was not fired in the kilns of the Shigaraki area, but rather in the kilns of the Higashiyama foothills, as Awataguchi ware and Nonomura Ninsei’s Omuro ware were also fired in a Shigaraki-style at the time.

The majority of the works are incense containers, water jars and tea bowls, all of which have a wabi-taste. What is interesting is that, while he was following the style of the Momoyama period, his elegant taste can be seen, and it seems that this reflects the transitional period from the Momoyama period to the early Edo period, when he lived. And the style of work he showed, including that of Nisen, is not seen in the so-called Kyoto-yaki, and when looking at the Kyoto-yaki of the early Edo period, it is something that cannot be overlooked. It seems that the existence of Koetsu and Kuchu was the motivation that later inspired Kenzan to take up pottery, and it is also thought that while Kenzan was learning the pottery techniques from Ninsai, he opened up a world of elegant pottery with a completely different feel, and that this was made possible by the bloodline of the so-called Rimpa school, which had its origins in Koetsu. In this sense, too, Kokusai Kobo played a role.

It goes without saying, but Kenzan was born in 1663 as the third son of Ogata Muneyoshi, a leading kimono merchant in Kyoto, and the younger brother of the painter Ogata Korin. His given name was Korin, and his nickname was Gohira. In 1687, the fourth year of the Jōkyō era, he changed his name to Ogata Shinshō (Kenzan used the name Ogata instead of Korin, which was his family name) when his father Sōken died, and he continued to use that name for the rest of his life. He was given a house in Takamine Koetsu-mura, the calligraphy of Gekko Sho’in, a set of books and other inheritance from his father, and probably because it was something he had wanted for a long time, he built a house at the foot of the hills of Rakusai Omuro Futagaoka and named it Shujido and lived there in seclusion. The story of what happened during this time is told in the “Shujyodo Ki” (Record of the Shujyodo Hermitage) written in 1690 by Gettan Doshō, a fellow student of Kenzan’s at the Saganoshijian temple, where Kenzan had been practicing Zen for some time. It is also thought that it was around this time that he began to call himself by the names Reikai and Tosen, and this reflects his youthful empathy with Zen and his preference for seclusion. It is thought that it was around this time that he learned the poetic inspiration from people of the Obaku school, such as Dokusho Seien, which later led him to become active in the production of unique elegant pottery decorated with poems and paintings. It is also likely that he learned his distinctive style of calligraphy during this period, but while his father, Soken, who was also a relative of Koetsu, often wrote in the Koetsu style, Kenzan’s style was based on the Teika style, and this seems to have been influenced by the fact that the calligraphy of Fujiwara no Sadaie had been particularly popular since the Momoyama period, and also by his friendship with court nobles such as Nijo Tsunahira from a young age.

Speaking of the Nijo family, it seems that Korin and Kenzan were both very popular with them, and according to the ‘Nijo Family Daily Record’, in the 6th year of the Genroku era (1693), Nijo Tsunahira visited the home of Ogata Shinsho, and according to the ‘Hozoji Documents’, in the following year, the Nijo family gave him a mountain villa in Narutaki Senkei, where Kenzan would later build his kiln.

It is not clear whether he already had the intention of opening a kiln in Senkei at this time, but it may have been the motivation for him to obtain land in Senkei, which could be said to be a more secluded area than Omuro. Speaking of the motivation for making pottery, it goes without saying that the most significant factor was his retreating to live near the kiln of Omuro Ninshō. It is thought that the first Ninnsei had already passed away by the time he set up his residence in 1690, and that his son had taken the name of the second Ninnsei. If this is the case, then the person who gave him the pottery method book when he opened his Narutaki kiln in 1709, “Nonomura Harima no Dajo Fujiyoshi”, seems to have been the second son of the first Ninnsei, Kiyojiro. The author speculates that after the death of the first generation, the second son Seijiro Fujira was given the title of Harima Dajo and succeeded him, perhaps because the first son Seiemon Masanobu died young or for some other reason. They continued to produce colored ceramics using the same methods as the first generation, but it seems that they were not producing particularly outstanding pieces when Fusho was visiting the kilns, as can be seen from the fact that the “Memorandum of Sadachika Maeda” from 1695 states, “The work of the second Nisei is poor”. The first Nisen was a famous artisan, but judging from the fragmentary information we have, it seems that his sons were all mediocre craftsmen, and that they ran the Omuro pottery business in the shadow of their father’s fame. However, he probably had the kind of personality that is common in second-generation family members. He befriended Fusho, who had come to him for help, and eventually taught him the pottery techniques that the first generation had worked so hard to perfect when he opened the Kenzan pottery kiln. He also helped Kiyoemon, who was thought to be the eldest son of Kiyoemon Masanobu. Anyway, when the Omuro ware was in this state, Shinsho often went from his hiding place to learn the pottery techniques, and in the end, in the 12th year of the Genroku era, he built a kiln in the residence he had received from the Nijo family and began his pottery-making life.

If we observe the events from March 1700 to the first firing, according to the documentary sources, we find the following: March 1700: Permission granted to Ogata Shinsho and Izumiya to build a kiln in front of the imperial palace. The name of the pottery is Kenzan. (From “Omuro Giki”)

July: Permission granted to Kenzan to receive firewood. (From “Omuro Giki”)

August: Nonomura Harima no Dajo Fujiyoshi gives Kenzan a book on pottery (Toko Hihyo).

September: Kenzan completes his kiln (Omuro Giki).

November: Kenzan’s first kiln. He begins to present tea bowls made by Ogata Shinsho to the Ninnaji-no-miya, and calls his pottery Kenzan-yaki (Omuro Giki).

In the 13th year of the Genroku era (1700), Kenzan presented a self-fired incense burner to the Nijo family (as recorded in the “Nijo Family Daily Record”).

It is recorded in the “Potter’s Handbook”, a book on pottery techniques written by Kenzan, that Kiyoemon and Sonebei of the Oshikouji kiln assisted him in his pottery work. Furthermore, he called his kiln the Kenzan kiln because the location of Senkei was to the north of Kyoto, and from then on he called himself Kenzan, but this was only a common name for his pottery or kiln, and in many cases he signed his paintings and letters with the name “Fukasho”, and never used the name Kenzan.

Unfortunately, it is still difficult to grasp the true nature of Kenzan ware from the Narutaki period. Judging from the pottery shards excavated from the kiln site and the surviving pieces, it seems that, even though he was taught the pottery techniques by Narihira, his style was quite different from the elegant wheel-made pottery and the glazed pottery that were the continuation of Narihira’s style. However, among the works thought to be from the early period, there are gold-painted and polychrome-painted sake cups, and these hint at the influence of Ninshō ware.

The pottery shards excavated from the old kiln sites include both high-fired and low-fired soft pottery (inside kiln firing), so it is clear that the Kenzan ware produced at Narutaki used both high-fired and inside kiln firing. However, Narutaki at that time was a place that was quite remote from the center of Kyoto, and even if it was on a domestic industry scale, it must have been inconvenient for the distribution of pottery, and judging from the fact that there are various descriptions of the study of pottery techniques in “Toko Hisshō”, it is thought that although they were producing pottery with a unique style within the Kyoto pottery of that time, it was probably not a very large industry. However, the fact that Kenzan’s name is mentioned in the Wakan Sansai Zue (A Comprehensive Survey of the Arts of Japan and China) published in 1713, along with the names of the pottery from Omuro, Kiyomizu and Fukakusa, shows that he was well-regarded in his day, and it is certain that Kenzan-yaki pottery had established its own distinctive style by the time it moved from its original kiln in September 1700 to its new location in Nijo Chojiya-cho, Kyoto, in 1713.

Of Kenzan’s works, particular attention should be paid to the so-called “white-glazed” dishes, which include the “Twelve-month colored paper plates” with the waka of Fujiwara no Sadaie inscribed on the reverse side, and which were made in 1702. , which were all fired in low-temperature kilns, and were unique to Kenzan ware, with pictures, waka poems, and literary works expressed in underglaze colors and iron oxide painting. Using this technique, Korin Kenzan collaboration plates were produced from around 1710 (the 7th year of the Hōei era) to the Shōtoku era (1711-16), with Korin, Kenzan’s older brother, drawing the pictures directly on the plates. Today, these are highly regarded as the most important works of Kenzan ware. Furthermore, in the book on pottery-making entitled “Tōji Seihō” (Pottery-making Methods) that Kenzan wrote in September of the second year of the Genbun era (1737), he himself states that “The initial designs were all drawn by Korin himself, and now the style of the paintings uses the same methods as Korin’s, or I have added my own new ideas, and I have passed them on to my foolish son Injin.” As he himself states, Kenzan ware was produced in the studio based on Korin’s designs, with Kenzan’s own unique designs added, and this is also evident when looking at the works that have survived.

Therefore, the works in the Kenzan ware that can be definitely recognized as having been made by Korin or Kenzan are limited to those that have Korin’s autograph seal and those that have Kenzan’s calligraphy or other inscriptions. Other works, such as the “lidded box with pine wave design in iron-red underglaze, overglaze gold and silver” (126) and the “lidded box with silver grass design in iron-red underglaze, overglaze gold” (Fig. 127), do not bear Korin’s signature, but there are some that are thought to have been painted by Korin , or those that are thought to have been painted in the studio based on Korin and Kenzan’s designs (in this case, it is not clear whether Kenzan himself also took part in the painting), or those that are thought to have been painted by a painter other than Korin (such as Watanabe Soshitsu), etc. himself is presumed to have written the poems and signed the pieces with the name “Kenzan”, and there are also pieces where it is unclear whether the painting and signature were done by Kenzan or by another potter. All of these pieces were produced as Kenzan ware throughout the period from Narutaki to Nijo Chojiya-cho. However, despite the fact that they were produced in a workshop, most of them were passed down as Kenzan’s work rather than as Kenzan ware, and this has caused a major problem in the identification of Kenzan ware, and there are still many aspects of his style that are unclear.

Furthermore, Kenzan moved to Edo around the 16th year of the Kyoho era (1731), but as he had passed on his pottery techniques and designs from the Narutaki period to his adopted son Inohachi, it seems that Inohachi produced Kenzan ware with the same name as his adoptive father Kenzan at the kiln he had set up at Shogoin in Kyoto , Inohachi produced Kenzan ware with the same name as his adoptive father Kenzan, and many of these pieces were passed down as works by the first Kenzan, rather than as Inohachi Kenzan.

As we have already mentioned, Kenzan’s style of pottery was quite different from that of Nisen, and first of all, there are no pieces that were turned on the potter’s wheel as elegantly as Nisen’s.

Most of his works were either molded or simple half-cylindrical tea bowls, or roughly-made vessels with a handmade feel. Rather than following the style of Nisen’s kilns, it seems that from the beginning he had a clear intention to make use of Nisen’s techniques for overglaze enamels and iron-oxide painting, and to incorporate the so-called Rimpa design style into his works . It is thought that the fact that he began his pottery career at the age of 37 was due to his passion to create something different from the traditional Kyoto-yaki pottery, including Ninshō pottery.

In this sense, when we look at Kenzan ware, it is clear that the main tone of the pottery style of Kenzan ware is the assertion of clearly expressing pure paintings on the pottery body, or showing a painterly decorative quality there. The most suitable technique for realizing this was the effective application of a white slip underglaze, and if you read the book “Toukou Hiyo”, you can see that he tried out all kinds of techniques, such as the Nisen-den or Oshikouji-yaki inner kiln pottery method . In this, as “Kenzan’s unique method of making pottery in an inner kiln”, it is written, “1. As I have already written before, the soil of the earth is the same in all eight countries, so if you make the base and then apply the clay that can be used for the top, and then fire it, it can be done in any way…”, as written above, it is true that any kind of clay can be used to make Kenzan-style ceramics, although the firing temperature and the resulting hardness of the clay will depend on the nature of the clay.

However, the excellent shapes of the pottery made on the potter’s wheel are still dependent on obtaining good quality clay, and it seems that Kenzan was quite careless about this point, and in fact there is not a single piece of pottery that shows the nimble handling of the potter’s wheel seen in the Nisei pottery. Although he showed a strong interest in glaze painting, the majority of his works were made using molds, or by cutting grooves into the surface of purchased unglazed clay to create a warped bowl shape. However, the world of deep and free design that more than makes up for its ordinariness is a world that entertains us fully, and even at the time when Kenzan ware appeared, it is thought that some connoisseurs showed a great deal of empathy. Otherwise, Kenzan’s kiln was not that large, so it is thought that not many pieces have survived to be seen by us today, and there would have been no later imitations.

In the 12th year of the Shoutoku era, Kenzan moved from Narutaki, where he had been producing a variety of wares for about 12 years, to Nijo Chojiya-cho in the city of Kyoto. The reason for the move is not clear, but I think it may have been due to the inconveniences of his pottery business. It was thought that the main products were mass-produced items such as sets of dishes, but this is still unclear. I suspect that he established his own style during the Narutaki period and then returned to Kyoto to actively produce Kenzan ware. However, perhaps Kenzan, who preferred seclusion, lacked the qualities of an entrepreneur, and it seems that the period in Chojiya-cho ended in disappointment, and in the 16th year of the Kyouhou era, he went to Edo to live with Prince Koukou of Rinnouji, and spent his final years in Iriya.

It is thought that he continued to make soft-paste ceramics in his private kiln in Edo, but we know very little about his work from this period. In 1737, he went to Sano in Shimotsuke Province (now Tochigi Prefecture) at the invitation of Okawa Kendo, Sudo Tokawa and Matsumura Kosho, and made ceramics and taught them as requested. It is not clear when he left Sano to return to Edo, but it is thought that the death of Prince Kokan, who had been his greatest patron in his later years, in 1738 was a great blow to him, and he dedicated six waka poems to the prince, beginning each with the six letters of the imperial title “Suho-in” that had been bestowed on him. On June 2nd, 1743, he is said to have left the following words as his last words before passing away: “I have lived a life of indulgence and shame for 81 years. I have drunk up the world of sand in a single gulp. The fleeting pleasures of this world are like a dream that passes in a flash.

Kenzan

Ogata Kenzan

Although his works are not as significant as those of Nisei and Kenzan, they are highly valued in the world of tea ceremony as a distinctive style of Kyo-yaki pottery. For this reason, we have selected a few of the works in this volume as precursors to Kenzan ware and illustrated them here.

Kakuansai Mitsuho, grandson of Hon’ami Koetsu, was born in 1601 (Keicho 6) and died in 1682 at the age of 82. He was already thirty-seven years old when Koetsu died in 16 37, so he had a close insight into Koetsu’s life in the last years of his life after living in a hermitage in Takamine. It is assumed that Koetsu’s influence on him was great, as he was a man of good character and had the air of a chief.

He was also friends with Horin Seisho of Rokuenji Temple, who left important materials on Kyo-yaki, and was related to Gankinya, the birthplace of Korin Kenzan. When Koho died, Gonpei was 20 years old.

Although it is said that the pottery of Kurosai, like that of Koetsu, was not a part of the family business, the range of Kurosai’s pottery is wider than that of Koetsu, as can be inferred from his remaining works, and he produced not only Raku tea bowls but also Shigaraki-sha works, which are characterized by their being called “Koro-Shigaraki”. However, Aerial Shigaraki was not fired in the kilns of Shigaraki Township, but probably in the kilns at the foot of Higashiyama, as Awataguchi ware and Nikiyo’s Omuro ware were also made in the Shigaraki-style at that time.

Most of the pieces are incense containers, water jars, and tea bowls, all of which have a wabi-style flavor. What is interesting is that his taste for elegance, while emulating the Momoyama style, seems to reflect the transitional period between the Momoyama period and the early Edo period in which he lived. The style of his work, which is not found in any other Kyo-yaki including Nisei, cannot be overlooked as a unique style when looking at Kyo-yaki of the early Edo period. It is also assumed that the existence of Koetsu and Kukanaka was the motivation that later inspired Kensan to pursue ceramics , and that Kensan, while learning pottery techniques from Ninsei, opened up a completely different world of elegant ceramics, which was made possible by the so-called Rimpa school, with Koetsu as its founder. In this sense, Koho Kakaisai played an important role in the development of the Rimpa school of pottery.

Needless to say, Korin Ogata was the younger brother of the painter Ogata Korin, and was born in 1663 as the third son of Ogata Soken, a leading kimono merchant in Kyoto. His real name was Tadamasa, and his nickname was Gonpei. In 1687, when his father left him, he changed his name to Ogata Shinsho (Kenzan wrote “Ogata” instead of “Korin”), which he retained for the rest of his life. He received from his father Soken a house in Takamine Koetsumura, ink seals by Tsukie Shoin, a set of books, and other inheritances, and built a house at the foot of Omuro Shujiga oka in Rakusai, which he probably had long desired, and named it Shuseido. The following is an account of his life during this period, written in 1690 by his fellow Zen master Gatan Dosojo under Dosho Dokusho of the Saga Naoshi-an, which Kenzan had been visiting for some time. It is estimated that it was around this time that he began to take on the titles of Reikai and Happa-Zen, which reflects his young age, his sympathy for Zen, and his preference for seclusion. It is thought that he learned his poetic ideas from Dokusho Seien and other members of the Obaku school during this period, as he later became a prolific potter of unique elegant ceramics with painted poetic and pictorial inscriptions. Although his father Soken, who was related to Koetsu, often wrote in the style of Koetsu, the reason why Kenzan’s calligraphy is based on the style of Teika is due to the fact that the calligraphy of Fujiwara no Teika had been especially favored since the Momoyama period among the Japanese styles since the Heian period, and also due to the fact that he had been close to the court noble Nijo Tsunahira from his early childhood. In addition, his friendship with the court noble Nijo Tsunahira may have played a role.

According to the “Nijo Family Daily Record,” Nijo Tsunapei visited the residence of Ogata Fukasyo in the 6th year of Genroku (1688), and according to the “Hozoji Documents,” in the 7th year of the following year, he received from the Nijo family the mountain house of Narutaki Senkei, where Kenzan later built his kiln.

It is not clear whether or not he already had the intention of opening the Senkei kiln at this time, but the fact that he was given the property in Senkei, which is a much more remote area than Omuro, may have been a motivation for him. Needless to say, the most important motive for his pottery production was his residence near the kiln of Nikiyo Omuro. It is assumed that Ninsei I had already died by the time he settled in the kiln in 2 Genroku, and his son took the name Ninsei II, and that “Nonomura Harima Taisho Fujiyoshi,” who gave him a pottery instruction manual when he opened Narutaki in 12 Genroku, was the second son of Ninsei I, Seijiro. The author speculates that after the death of the first generation, Seiemon Masanobu died prematurely or for some other reason, and his second son, Seijiro Fujiyoshi, was given the title of “Harima Ojyo” again and took over. Although he was firing colored pottery and other ceramics using the same techniques that had been used since the first generation, it is likely that he was not producing such excellent pieces when Fukasyo was a close visitor to the kiln, as evidenced by a note by Maeda Sadachika in Genroku 8, “Nisei ni nisei ni okeru shite ni gozasou. Although Ninsei I was well known as a master potter, his sons were all mediocre potters, and it seems from the fragmentary data that they were run by the first generation, Yomitsu, who ran the Omuro Pottery business. However, they must have had the good nature of people that is common in the second generation. He was in close contact with the approaching Fukasho, and eventually passed on the pottery methods that the first generation had painstakingly studied when he opened the kiln of Qianzan-yaki. When Omuro-yaki was in such a state, Fukasyo often went from his retreat to learn pottery techniques, and finally, in the 12th year of the Genroku era, he built a kiln in a house that had been given to him by the Nijo family, and began to make pottery.

According to the “Essentials for Potters,” a handbook on pottery production written by Inzan, Seiwemon and Magobei of Oshikoji Pottery assisted him in the production of pottery. The name of the kiln was changed to “Qianzan” because of the location of Quanxi, which is in the direction of Qian from Kyoto, but this was only a common name for the kiln or the name of the pottery.

Unfortunately, it is still difficult to grasp the true nature of Qianzan ware during the Narutaki period. Based on the pottery shards excavated from the kiln site and other artifacts, it seems that even though he was taught the pottery method by Inkiyo, his style was not an extension of the Inkiyo style of neat wheel throwing and beautiful overglaze enameled pottery, but rather a very different style from the beginning. However, there are examples of gilded and color-painted sake cup bases among the early pieces, which suggest some of the influence of the Inqing ceramics.

The pottery shards excavated from the old kiln site include both main kiln ware and low-fired soft ware (inner kiln ware), which clearly indicates that Narutaki’s Qianzan ware was produced using both main kiln ware and inner kiln ware. However, Narutaki at that time was quite remote from the center of Kyoto, and even if it was a cottage industry, it must have been an inconvenient place for pottery production and distribution. However, the pottery was not a major occupation for him. However, the fact that Kensan’s name is mentioned in “Wakan sansai zue” written in 1713 (Shoutoku 3), along with pottery from Omuro, Kiyomizu, Fukakusa, etc., indicates that Kensan ware was highly regarded by the public, and it is also clear that Kensan ware had established a unique style from its opening in September of Genroku 12 to its move to Nijo Choshiya-cho, Kyoto, in Shoutoku 2. It is certain that the kiln established a unique style of its own.

The most notable examples of Qianzan ware are the so-called “12 months colored paper plates” with underglaze white glaze, which are all fired in a low-fired inner kiln, and are characterized by the use of underglaze color and underglaze ironware to represent paintings, waka poems, and poetic verses. They were all fired in a low-fired inner kiln, and were unique products of Qianzan ware. Using this technique, Korin Kienzan plates were produced from around 1710 to the Shotoku period (1711-16), painted directly by his elder brother Korin, and are now highly regarded as the most important pieces of Kienzan ware. In addition, in a book he wrote in September of 1737 titled “Ceramics Making Methods,” Korin Kensan himself stated, “The first paintings were all done by Korin himself, but now the style of painting is the same as Korin’s, and I have also shared my new ideas with him and passed them on to my children. As stated by Korin himself, Kensan ware was based on Korin’s design, with Kensan’s unique design added to it, and this is evident from an overview of the works that have survived.

Therefore, among Korin’s works, those that can be attributed to Korin or Kensan are limited to those with a signature in Korin’s own hand and a poem or inscription by Kensan on it. Other works, such as “Lidded Ware with Design of Pine Waves in Iron and Silver underglaze Enamels” (126) and “Lidded Ware with Design of Pine Waves in Iron and Silver underglaze Enamels” (Figure 127), do not bear Korin’s signature, but are presumed to have been painted by him, or to be self-portraits by Korin or Kienzan, or to have been designed and painted in his workshop (in which case, Korin and Kienzan may have been involved in the painting process). Some are presumed to have been painted by Korin or Kensan (in which case it is not clear whether Kensan himself was involved in the painting), some are painted by artists other than Korin (such as Watanabe Soshin), and some are presumed to have been signed by Kensan himself with a poem or the name “Kensan”, and some are painted and signed by other artists (it is not clear whether they were by Kensan or other artisans). All of these items were produced as Inzan ware from Narutaki through the Nijo Choshiya-machi period. However, despite the fact that they were produced in a workshop, most of them were not identified as Qianzan ware, but rather as the work of Qianzan, which has become a major problem for Qianzan ware connoisseurs, and there is still much that remains undetermined about the style.

Inohachi seems to have produced Qianzan ware with the same name as that of his adoptive father, Qianzan, at a kiln established in Shogoin, Kyoto, and many of these pieces were passed down through the generations not as Inohachi Qianzan, but as the work of the first generation. Many of these pieces were passed down through the generations not as Inohachi Kenzan, but as the work of the first Inohachi Kenzan.

As mentioned above, the pottery style of Qianzan is quite different from that of Insei, and first of all, his pottery is not wheel-thrown as elegantly as Insei’s. Most of his pieces are molds or simple half-turns.

Most of them are molds, simple semi-tubular bowls, or handmade wares. It seems that rather than following the style of Insei’s pottery by attending his kiln, he had a clear desire from the beginning to create a so-called Rimpa school design by utilizing the Insei tradition of color and rust painting techniques. The fact that he began making pottery at the age of 37 is thought to have been the result of his passion to create something unique and different from traditional Kyo-yaki pottery, including the Ninsei style.

In this sense, the keynote of Qianzan ware is clearly its insistence on the expression of pure painting on the ceramic body, or the display of pictorial decorativeness. The most appropriate ceramic technique for realizing this was the effective application of white underglaze enameling, and a reading of “The Essentials of Pottery” will naturally show that all kinds of ceramic techniques were actually tried using the internal kiln pottery methods of the Ninsei and Oshikoji styles. As he writes in his book, “The translation of the clay used for the preparation of the clay is as described in the previous section: ‘Any clay from any of the eight countries can be used for the preparation of the base, and any clay from any of the eight countries can be used for the top. As he wrote, ”I am not a fan of the technique of wheel-thrown pottery, but I am interested in the technique of wheel-thrown pottery.

However, the excellent wheel-thrown forms are only possible when the clay is of high quality, and Qianzan seems to have been quite indifferent to this point, and none of his vessels show the same lightness on the potter’s wheel as the Insei ceramics. Although he showed a strong interest in glazed branching with painting as the theme, most of his pottery is characterized by the use of molds, or the use of the bare clay of purchased pieces, or the so-called “waribachi” style of bowls, which are formed by incising into a ginkgo shape to bring about a change. However, the world of tasteful and free designs that more than compensate for the mediocrity of the pottery are pleasurable enough for us to enjoy, and even at the time when Qianzan ware first appeared, some eccentrics must have been very sympathetic to the pottery. Otherwise, Qianzan’s kilns would not have been so large that there would not have been as much left for us to see, nor would there have been any later imitations of his work.

In the second year of the Shotoku era, Kenzan moved from Narutaki, where he had been producing various products while his kiln smoked for about 12 years, to Nijo Choshiya-cho in the center of Kyoto. The reason for the move is not clear, but I believe it may have been due to the inconvenience of the pottery business. It has been speculated, but it is still unclear, that the pottery produced during the Choshiya-cho period consisted mainly of mass-produced items such as matsuri-mono, since the town did not have its own kiln but borrowed kilns for production. I suspect that he established his own style during the Narutaki period and returned to Kyoto to actively produce Qianzan ware. However, as I thought, the entrepreneurial qualities may have been lacking in the Kensan who preferred seclusion, and it seems that his time in Choshiya-cho ended in disappointment.

It is assumed that he fired soft pottery in his own kiln in Edo, but the details of his works from this period are not known at all. In 1737, at the invitation of Okawa Kendo of Sano, Shimonokuni (Tochigi Prefecture), Sudo Togawa of Koshina, and Matsumura Tsubo-Seitei, he went to Sano to make pottery and teach pottery making as requested. Although it is not known when he returned to Edo from Sano, it is assumed that the death in Genbun 3 of Prince Koukan, who had been the greatest patron of Kenzan in his later years, must have been a great blow to him. It is said that on June 2, 1743, he passed away, leaving behind the following poem: “In 81 years of cruelty and misery, I have swallowed a mouthful of water, and the world is a big thousand floats and happy times, but if it passes, it will be the dream of akekure.