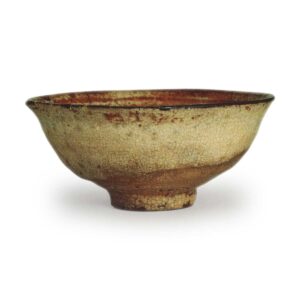

Height: 6.2-6.4cm

Diameter: 14.1-14.4cm

Outer diameter of foot ring: 4.7cm

Height of foot ring: 0.9cm

It is probably after the Meiji period that this tea bowl came to be considered as a Ido-waki, but the clay and glaze are quite different from those of the Nagasaki and Hakubai tea bowls.

The four tea bowls listed in the Taisho Meiki Kan (A Guide to Famous Tea Bowls of the Taisho Period) as Ido-waki are not all of the same type: they include tea bowls from Nagasaki, Shiraume, and the Yabuuchi family, as well as one from the Toba-ya family, one of the Ten Great Tea Masters of Edo. As you can see, there is no common agreement about the meaning of the phrase “wellside”. It is thought that tea masters from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period interpreted the meaning of the phrase “wellside” as they saw fit.

The clay of Daibizan is a dark brown with a high iron content, and the glaze that covers the whole piece melts extremely well, so it does not have the rough glaze of an Ido-yaki piece, but rather a glossy, lustrous glaze like that of the Onikuma River. However, the glaze is quite thick, so the cracks are not very fine, and the foot ring has a kind of peony-skin pattern, but this is not as dignified as the Ido ware. Compared to the white plum blossoms, the base and glaze of these bowls are quite different, but they do have some similarities in shape, such as the low foot ring with a bamboo-joint shape and the slightly turned-up rim, and they are almost identical in terms of their production.

The glaze is rich in variation, and the two-tone color of the yellowish-brown and brown hues gives a gentle yet deep flavor, and is also rich in softness. However, I think the beauty of this tea bowl lies in its shape. The simple, flawless shape of the bowl, from the foot to the rim, is pleasantly spacious in the palm of the hand, and the shape of the bowl is well-rounded, so the weight is also just right. There are four marks on the foot, but none on the inside.

The origin of the Daibizan name is unclear, but the characters for “Daibizan” on the paper pasted to the inside of the box lid are quite old. However, the box itself does not appear to be as old as the paper, so it is likely that the name was added later. Perhaps the name was given because the tea bowl has a gentle appearance, similar to the scenery of Daibizan in Kyoto. The details of its old history are not clear, but it later came into the possession of the Fujita family in Osaka, and then was owned by the tea master Kameyama Sogetsu in Tokyo. Although it was previously almost unknown, according to the tradition, Tanimatsu Kando Toda Rogen was said to have highly valued it, and it may have been Tanimatsuya’s recommendation that led to it coming into the possession of the Fujita family.